Balance and Sharing: Women’s Childcare Time and Family’s Help

2018-10-31ZhengZhenzhen

Zheng Zhenzhen*

Abstract: It is of crucial importance for professional women to strike a balance between childcare and work. Help from family can effectively reduce women’s time spent on childcare. Based on relevant survey, this paper successively analyzes the time of mother, father and grandparents invested in childcare and explores how women are supported by their family in this duty. Infant and childcare can be as time-consuming as a full-time job. Mothers have always played a primary role in infant and childcare, while grandparents,offering a helping hand to effectively alleviate the mother’s workload, can play an alternative role, which is of great significance. This is particularly true in early childhood, when more than 40% of Chinese children are under the care of grandparents, with relatively limited participation of their fathers.Childcare gap between mothers and fathers is even larger in rural China. It is quite common for a family to turn to nursery services when their child are three years old to significantly alleviate the mother’s childcare burden. When it comes to the design of relevant public policies and projects, consideration should be given to the role of each family member in taking care of infants and children in different growth stages to explore more options for childcare.More specifically, in addition to motherhood, grandparents’ support should be valued, and fatherhood should be enhanced.

Keywords: women; labor force participation; childcare; time utilization; family policy

1. Introduction

Female labor force participation, along with their work-family balance, is an ever-lasting topic in the international community. The reason why this issue keeps arousing public debates and policy concerns lies in the fact that, although closely related to economic and social development, it remains to be properly addressed. For women, labor force participation coincides with the coming of their prime child-bearing age. A woman new to the workplace is likely to become a new mother in a few years. Both roles are tremendously time and energy-consuming, which is a major challenge for women. In the 1950s, Chinese women in urban and rural areas began to engage in economic and social activities, giving rise to a conflict between childcare and labor force participation. In the 1970s,the Chinese government’s advocacy of family planning was timely supported by the public. One explanation could be that Chinese women were eager to be alleviated from childcare pressure. The drastic drop in the birth rate largely resulted from the implementation of the “one-child” policy which transformed childbirth to a “one-time” experience but also disguised the essence of this issue. With the extensive introduction of the “two-child” policy in recent years, more and more young couples feel the salient contradiction between childcare and their life goal, or between childcare and economic wellbeing. Public concerns such as “dare to dream but dare not try” and “unable to afford two children” are frequently reported and discussed in the Chinese media. Relevant surveys also show that the childcare-work conflict constantly puts young couples on the run and that childbirth becomes a disadvantage for women in the labor market. In such a context, how to relieve the pressure of having a second child has become a hot topic. Currently,surveys indicate the actual number of births among married couples is far below the desired number.This indicates that people’s child-bearing desire is restrained by multiple adverse factors, which cannot be easily solved by easing the strict family planning policy. Yet, related discussions, even in the academic community, tend to center on women’s maternity and childcare leave. Debates on how to loose social restrictions on childbirth also mostly target women.

Chinese women in urban and rural areas began to engage in economic and social activities.

Childcare-work balance is not just the business of mothers, but that of all families and even the entire society. Women are not exactly alone and helpless in childcare. Instead, the support from their family, particularly the elder generation,significantly alleviates their childcare burden. In a typical Chinese family structure, a couple usually have one or two children. With an increasing number of the “only-child” generation entering the stage of marriage and childbirth, more and more families are “4-2-1” or “4-2-2” structure (i.e. four grandparents, two parents, one or two children).Except in the stages of pregnancy and lactation,which require mothers’ sole and full participation, in the remaining stages of childcare, family members can help at various degrees. Human resources that are involved in childcare can be concentric circles centering on a child. The closer to the circles’ center,the greater the workload. As the child grows, he or she is looked after by a larger group, extending from parents, through grandparents to people outside the family. Thus, childcare should not be deemed as a duty exclusive to the mother. When it comes to the alleviation of women’s childcare burdens, all possible members, whether they are within or outside the family, should be considered.The drafting of relevant support policies requires due considerations for helpers, as well as mothers.From the perspective of time devoted to childcare,following the concentric-circle pattern, this paper analyzes women’s time spent on childcare, with and without family support, and explores how to mobilize childcare resources both within and outside the family to help women to better cope with the family-work dilemma.

2. Literature review

Time is a limited and can neither be recycled nor re-utilized. Studies on time utilization are usually done from the perspectives of labor supply,family, leisure, etc. Many of these studies approach women’s time allocation as part of a lifestyle. The gap in housework hours between women and men is another topic that triggers heated debates. From a perspective of family life cycle, right from the beginning, women have been faced with a series of time-allocation challenges, trying to strike a balance between work, further education, childcare,housework, elderly-care, leisure and rest. Relevant research indicates that women, when not at work or rest, spend most of their time doing housework and taking care of the young and the elderly.One indisputable fact is that the duty of childcare forces women to reduce their participation in, or simply withdraw from, the workplace resulting in a significant decrease in income. This problem remains unsolved even in developed countries.①Connelly, 1992; Ma, 2014

The practices in some developed countries over the past years indicate that effective policy interventions can alleviate the conflict between work and family that confronts women on childcare duty.②Brewster & Rindfuss, 2000By contrast, relevant practices in some countries in East Asia indicate that policy inventions can hardly de-escalate such a conflict because of men’s far-from-sufficient participation in childcare.③Kim & Zuo, 2017The sharing of housework between wife and husband is key to the re-division of labor within a family. Based on the micro-analysis of women’s fertility and work participation done by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), it was discovered that men’s engagement in housework reduces the conflicts between childcare and work that confront women.①de Laat & Sevilla-Sanz, 2011Another study conducted in Sweden, however,reveals that although a Swedish father is entitled to have a 1-year childcare leave, 49% of Swedish families rely primarily on the mother to look after children, while 42% of the families have their newborns under the care of both parents, with father more likely to take a childcare leave six months after the baby is born.②Eriksson, 2015These statistics support the continuous existence of the labor division between mother and father.

Based on the results of the 2003-2004 American Time Use Survey (ATUS), Kimmel and Connelly discovered that a mother’s childcare time increases with the number of children and the costs of nursery services and decreases as the children grow older.③Kimmel & Connelly, 2007In a family with both parents working fulltime, family time allotment is often agreed by the couple through negotiation. For them, childcare is teamwork and the father shares this duty with the mother. The same data also reveals that a mother’s income is the factor that determines the parents’ time spent on childcare and leisure.④Connelly & Kimmel, 2009This study mainly targeted couples whose youngest child was under 13 and focused on their time spent on childcare and housework respectively on workdays and during weekends. According to the research findings,couples with higher incomes tend to spend more time on childcare; couples with a smaller income gap tend to share childcare duties on a fifty-fifty basis; women with higher incomes tend to spend more time on childcare and less time on leisure on workdays; men who earn less than their wives tend to spend more time on childcare during weekends,and spend more time on childcare and less time on leisure on workdays when their wives work overtime. Through comparison with the results of a similar survey conducted in the 1970s, social progress has enabled more equal negotiations on the division of childcare labor between couples.

In recent years, there have been an increasing number of grandparents engaged in childcare in some developed countries. According to research done by US scholars, women with young grandchildren tend to retire earlier;⑤Lumsdaine & Vermeer, 2015while 28% of British grandparents take care of their grandchildren under 16.⑥Buchanan, 2014Other relevant research indicates that childcare in China shares similarities with that in developed countries while at the same time features its own characteristics. According to the World Development Report, published by the World Bank in 2015, in contrast with many countries’ efforts to increase women’s participation in the workplace China saw such participation declining, from 73%in 1990 to 64% in 2013. This decline was the result of a re-division of labor and re-allocation of time within Chinese families triggered by a mixture of economic, social and institutional factors.⑦Wu, 2015Still,childcare is a primary barrier that prevents young women from participating in professional work.According to China’s census findings in recent decades, raising “infants/children” was an even bigger barrier to women’s career development in 1990 and 2000 than it was in 1982. Such a negative impact becomes stronger as time goes by.①Maurer-Fazio et al., 2011A 2010 survey on Chinese women’s social status revealed that there was a substantial rise in women’s suspension of work in non-agricultural sectors due to childbirth during the prior two decades; that this figure rose from 10.3% in the period between 1981-1990 to 36.0% in the period between 2001-2010.②Huang, 2014For most women employed irregularly, raising “infants/ children” has the strongest negative impact on their employment prospects. Those living with their preschool children are far less likely to be employed than those living with their school-age children or without any child.③Maurer-Fazio et al., 2011

grandparents engaged in childcare in some developed countries

Recent years has seen an increasing number of studies on Chinese women’s engagement in childcare and housework. From a perspective of time utilization, Zhou Yun and Zheng Zhenzhen,④Zhou & Zheng, 2015as well as Li Yani⑤Li, 2013discovered that marriage and childbirth did not substantially reduce women’s work time, but increased time spent on housework and that in order to strike a balance between work and family women tended to sacrifice their time for leisure or even sleep.Although mother plays a primary role in infant and child care, father to some extent also shoulders this duty. Grandparents are contributing more to this“job” as well with an increasing number of middleaged and elderly people (over 50) helping to look after their young grandchildren thus alleviating a young couple’s housework burden. According to the Report on Elderly Women in China, some 70% of elderly women have taken care of their grandchildren for their sons; while some 40% have had done this for their daughters.⑥Jia, 2013For a multi-generational family,support from middle-aged or elderly parents in housework can effectively boost a young woman’s participation in professional work.⑦She, et al., 2012Against the backdrop of a young labor force, many elderly parents have moved to bigger cities to live with their grown-up children to help them with childcare and housework. This is particularly true for those with only one grown-up child. Some surveys reveal that the elderly migrants in Shanghai, nicknamed the“elderly drifters,” have come all the way across China chiefly to help care for their grandchildren.①Zhang & Hu, 2016

At present, micro-data needed for an in-depth analysis of Chinese women’s childcare time and influencing factors is limited. Most of the collected information on time utilization is about time spent on housework, which covers house cleaning, cooking,shopping, maintenance of household facilities, infant and child care, the elderly/disabled care, etc. In fact,these housework are different. Childcare is a daily activity which requires 24-hour attention. For example,infants and children should be fed and sleep according to a fixed timetable every day. By contrast, housework such as laundry can be delayed until the weekends.Some housework (cleaning, cooking and shopping)can be easily done with help from outside the family.For time-saving purposes, quick-frozen food and takeaway are preferred to family cooking and homemade dishes. When it comes to childcare, however,there are simply no other feasible alternatives. Analysis of women’s childcare requires the separation of their childcare time from other housework. However,relevant Chinese surveys and research tend to use“housework time,” a more extensive and vague term to refer to both childcare and other household chores.Some analysis reveals that women’s time spent on housework does not decrease as their children grow up.②Yang, 2015This discovery has a lot to do with the inclusion of childcare with general housework.

3. Data introduction

Based on the 2014 tracking survey data on family planning development in China and the 2010 follow-up survey on the fertility intentions and behavior in Jiangsu province, this paper focuses on childcare time, respectively analyzing the contributions of father and grandparents to childcare and the impact of nursery services on reducing women’s childcare time.

China’s tracking survey on family planning development is nation wide. The first survey,conducted in 2014, included a total of 32,494 sample households,③Department of Family, National Health Commission of the PRC, 2015from which 7,153 questionnaires targeting infants and children aged 0-5 were collected. According to the survey data, 65.5% of the children lived in village-type communities; boys accounted for 53.2% of the child population; there was an even distribution of children at all ages from 0-5. Regarding childcare information, the survey followed the main caregivers’ performance for six months, the fathers’ and mothers’ respective daily parent-child time and weekly time of companionship in the last six months, as well as whether the children attended kindergarten. From this information,researchers identified the main caregivers of infants and children at different ages, parents’ time spent with children, other family members’ participation in childcare, and thereby analyzed and estimated how much the support from other family members can reduce women’s childcare time. However, for grandparents who were not primary caregivers but childcare participants, the above data could not reflect how much their help reduced parents’childcare time.

This paper also analyzes grandparents’participation in childcare based on the findings of the 2010 follow-up survey on the fertility intentions and behavior in Jiangsu province, which was a 7-year long program jointly launched by the former Population and Family Planning Commission of Jiangsu province, and the Institute of Population and Labor Economics of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2006. The research team conducted a baseline survey and two follow-up surveys on fertility intentions and behavior in six counties and municipalities of Jiangsu province. The 2010 follow-up survey mainly collected information on childcare (under 6), including mothers’ daily care time, parents’ and parents-in law’s daily care time (if any), as well as who slept with and took care of the child (children) at night.①Research Team of Jiangsu province on the Public's Fertility Intentions and Behavior, 2011The information collected reveals grandparents’ participation and contribution and how much their participation can reduce mothers’ childcare time.

Over the past years, I have collected relevant qualitative data from many urban and rural investigations and interviews. Such qualitative data,along with existing research findings, are applied to analyze women’s arrangements of childcare time and the respective impacts of family help and social support on women’s childcare time.

This paper adopts descriptive statistical analysis,relevant simple data analyses and multivariate analysis to control the impact of other variables.

4. Major research findings

4.1 Mother remains the primary childcaregiver

Regarding the primary child-caregiver and parents’ childcare time, this paper is mainly based on the research findings of the 2014 tracking survey data on family planning development in China.②Department of Family Planning and Development, National Health Commission of the PRC, 2016According to the 2014 research findings, mothers remain the primary child-caregiver and mother’s time spent on childcare varies during the different stages of infant and child growth. Given that mothers are supposed to be responsible for breastfeeding and enjoy maternity leave, at the infant/baby stage,mothers are the primary caregiver although other members of a family may help but can only play a supporting role. At the child stage, however, family members can share the childcare duties or even replace the mother.

At the infant/baby stage, mothers accounted for the largest proportion of primary caregivers. For all infants under one full year, 67.1% were primarily taken care of by their mothers; 6.2% were jointly taken care of by their parents; less than 20% were primarily taken care of by their grandparents (15.5%by father’s parents and 3.5% by mother’s parents);some 6.7% were jointly taken care of by the whole family (mother, father, mother’s parents and father’s parents); the remaining few were taken care of by others outside the family (e.g. baby-sitters). Although mothers remained the primary caregivers at the infant/baby stage, there were differences between urban and rural China. Mothers accounted for 57.1%of all primary caregivers in urban China, as opposed to 72.8% in rural China. In rural China, infants/babies were primarily taken care of by their mother,while in urban China, professional women had to leave the childcare task to their elder generation(parents) once their maternity leave was over. Breast feeding was practiced by most mothers, with 87.3%of Chinese babies having the experience of being breastfed. Even so, the breastfeeding duration varied.About half of the babies enjoyed breastfeeding for no more than six months, which allowed their mothers to return to work sooner.

For children aged 1-5, mothers remained the primary caregivers. However, as the children grew older, their mother’s childcare time decreased significantly. For children aged one, there was a drastic drop in the proportion of their mother being the primary caregiver to 48.6%. As the children grew older, this figure saw slight fluctuation around 40% and the proportion of parents’ joint care was on the gradual rise to 10.9% when the children turned five. More specifically, 44.4% of children in this age group (aged 1-5) were primarily taken care of by their mother; 7.7% were jointly taken care of by their parents and others; 1.7% were primarily taken care of by their father; 53.8% were exclusively taken care of by their parents. Also, in this stage, grandparents were the main helpers, with 41.1% of children primarily under the care of grandparents, 4.2%under the joint care of parents and grandparents and only 0.3% primarily or partly under the care of babysitters.

Being the primary caregivers, mothers spent the most hours in accompanying or taking care of children. Chart 1 exhibits father’s and mother’s respective daily hours in accompanying their children in different age groups. For both father and mother, their companionship with infants/babies was the longest. For all infants under one full year,their mothers’ daily companionship exceeded nine hours, with half of those mothers spending 10 hoursor more on childcare per day. For children over one year old, as they grew older, mother’s daily hours of care and companionship significantly decreased.

Chart 1 Parents’Daily Hours spent with Children in Different Age Groups

There was a marked rural-urban gap in childcare and companionship. Rural mothers spent more time than urban mothers with their children. At the infant stage, rural mothers spent an average of 9.2 hours per day with their children, as opposed to urban mothers’ 8.7 hours. For rural children in all age groups, fathers’ companionship remained far less than that of mother. By contrast, the mother-father gap in companionship hours was smaller in urban China. This is probably due to the fact that genderbased division of labor in rural families was clearer than that in urban families. Besides, this also had something to do with rural young men’s being away for work in cities.

According to the above statistics, infants/babies under one full year had the highest degree of mother dependence, childcare support from grandparents to some extent played an alternative role. This was reflected in mother’s daily hours spent with children.As the children grew from one to two years old,mother’s companionship hours were on the decline and father’s companionship hours also saw a slight decrease. Such a downward trend had a lot to do with grandparents’ participation in childcare. The participation of father and grandparents in childcare inevitably has an impact on mother’s childcare time.

4.2 Father’s limited role in infant and child care

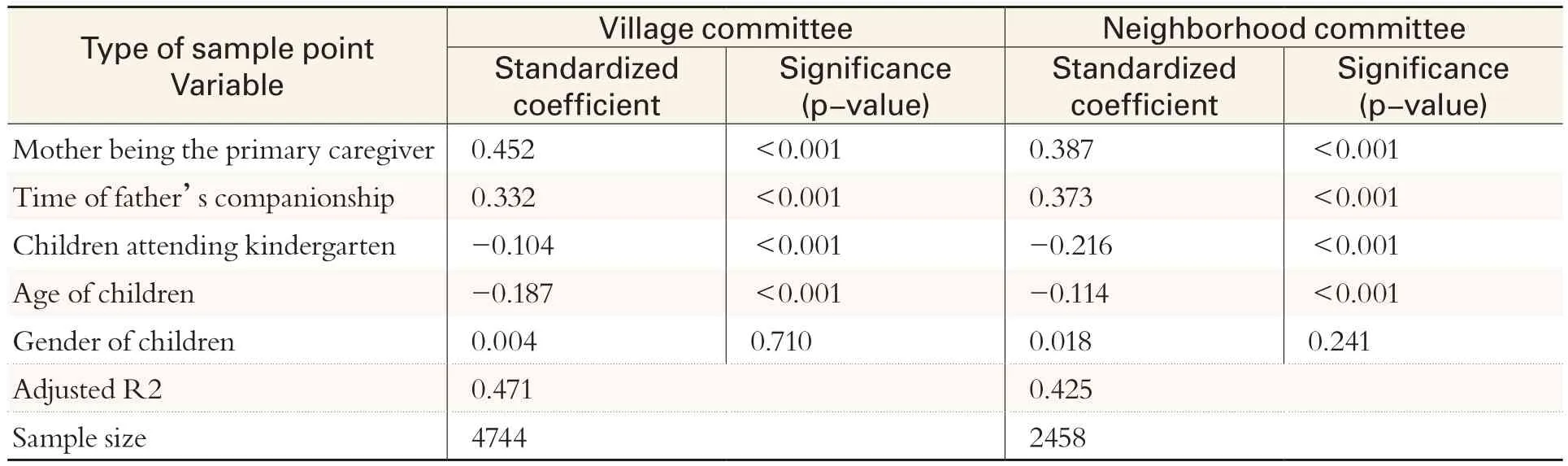

Relevant survey results show that fathers participate in the care of children at various degrees and accompany them at all age groups. Although their childcare contribution is far smaller than mothers, fathers can share the childcare burden. To further explore the impact of father’s participation on the reduction of mother’s childcare time, this paper carries out a multiple linear regression analysis (MLR) with other variables controlled.Considering the differences between urban and rural residents in parenting and companionship,this paper places research samples into two model categories, i.e. village committee (representing rural China) and neighborhood committee (representing urban China). For this model fitting, only significant variables and necessary controlled variables are retained. According to this model, the dependent variable is mother’s daily hours spent with children;the independent variables are father’s daily hours spent with children and whether the children attend kindergarten; the controlled variables are children’s age, gender, and whether their mother is the primary caregiver. Table 1 shows the results of this regression analysis.

Table 1 Results of MLR Analysis of Mother’s Companionship (parameter estimation and significance)

According to Table 1, in both urban and rural China, when mothers were the primary caregivers,they spent more daily hours with their children and played the most significant role in this model. On the other hand, father’s companionship was also of great importance, although it did not truly help reduce mother’s childcare time. In fact, there was a positive correlation between father’s childcare time and that of the mother’s. In other words, mother’s daily hours spent with children increased with that of the father’s, which means father’s companionship did not replace that of the mother. One possible explanation could be that fathers tended to cooperate with mothers on childcare, instead of taking care of the children by themselves.

Since fathers just participated in childcare without replacing mothers as primary caregivers,there were bound to be more helping hands.However, this were not covered by this survey and therefore need to be explored through other surveys and research. Moreover, kindergarten attendance could help significantly reduce mothers’ daily hours spent with children, which is to be further discussed in the next part. Last, child gender was not a notable factor in the above model, suggesting no gender preference in mothers’ childcare time investment.

4.3 Grandparents’ effective help with childcare

Grandparents can help take care of children when they are little (aged 1+). The 2010 followup survey on the fertility intentions and behavior in Jiangsu province also covered grandparents’contributions to childcare. The results revealed that some 90% of interviewees with children enjoyed childcare help from parents or parents in law and that some 40% of their children slept with grandparents at night. According to the female intervieweeswith children, their average daily childcare time was 6.4 hours (6.1 hours for those with help from grandparents and 9.1 hours for those without help from grandparents). As shown in Chart 2, the help from grandparents reduced mother’s childcare time.

Chart 2 Women’s Daily Hours Spent with Children Under Six (2010)

Chart 2 reveals that women without the elder generation’s help spent a minimum of eight hours per day on childcare; even when their children turned three years old and attended kindergarten, there was still no significant change in this regard; and that these women could barely participate in other economic and social activities. Because childcare is a time-consuming duty, women of child-bearing age would take the childcare help from the elder generation into account when considering whether to have a second child. Given that over 80% of female interviewees were engaged in work, particularly non-agricultural production, “childcare help from the elder generation” became a defining factor for women’s decision on whether to have a child.①Research Team of Jiangsu Province on the Public’s Fertility Intentions and Behavior, 2011Through the interviews, it was discovered that one common feature for most women with at least two children was that their “second child” plan was actively endorsed by the elder generation. Except for some special cases, most postpartum women had help from their parents or parents-in-law and therefore could return to work after maternity leave.It was not common for these women to abandon their jobs and stay home to look after their children.Thus, it can be seen the elder generation’s help is of crucial importance to women to reduce childcare time, and balance work and childcare.

For grandparents helping with infant and child care, their participation meant total dedication. As shown in Chart 2, for families with children under 6 years old, the daily childcare help from participating grandparents was about 7-8 hours, which virtually prevented them from engaging in other work. Due to nursery service shortages in today’s society,childcare duties in a Chinese family requires the full dedication of at least one family member.

4.4 Nursery services’ effective alleviation of mother’s childcare pressure

The results of relevant surveys all indicate that entrusting their children to kindergarten is a popular choice for parents both in urban and rural China. According to the results of China’s tracking survey on family planning development, for children aged 4 and 5 (except a small part being primaryschool students), their respective kindergarten attendance reached 91.7% and 94.7%. Regarding this, difference did exist between urban and rural China. In urban China, of all 4-year-olds, 3.6% did not attend kindergarten; by contrast, this figure in rural China was 10.9%. Even so, a clear majority of rural children of this age attended kindergarten.②Department of Family Planning and Development, National Health Commission of the PRC, 2016The 2010 follow-up survey on the fertility intentions and behavior in Jiangsu province also revealed that over 90% of children at the right age also attended kindergarten. In terms of kindergarten conditions and service quality, there was a significant gap between urban and rural China. Nevertheless,parents of young children would try to make the most of child nursery services (if any).

For grandparents helping with infant and child care, their participation meant total dedication.

For the group aged 3, only 63.8% attended kindergartens; while for the group under 3,kindergarten/nursery attendance was particularly low (e.g. 14.4% attendance rate for 2-year-olds),which was related to a lack of childcare institutions accepting children under 3.

The results of MLR analysis in Table 1 revealed that children’s kindergarten attendance significantly reduced their mothers’ time spent with them. Such an effect can be further amplified in bigger cities and with grandparents’ help and better nursery services(not shown in Table 1). Relevant international practices have indicated that government-led/supported child nursery services in areas at higher levels of urbanization and industrialization can effectively alleviate the tension between childcare and professional work and can therefore help enable couples’ wish for fertility. For example, according to a comparative study on the fertility rates in different areas of South Korea, government’s introduction of a series of support policies was closely related to the higher utilization degree and fertility level.①Choe & Kim, 2014

5. Conclusion and discussion

Women are the major undertakers of unpaid housework. Infant and child care is a key part of this housework and is also a major challenge facing women and families in the long run.Relevant survey findings reveal that mothers are without doubt the primary child-caregiver, and grandparents’ help significantly reduces mother’s childcare time, which is particularly true when the child turns one year old. By contrast, fathers play a limited role in this regard and their time invested in childcare cannot replace that of the mothers. As the infants and children grow older, mothers can gradually have part of their duties transferred to others. Grandparents’ participation in childcare,along with nursery services, can effectively alleviate the childcare pressures on mothers. The survey findings also reveal that for both mothers and grandparents, infant and child care is arguably a full-time job, although nursery services can help reduce family childcare time.

Infant and childcare requires time investments from an entire family. Society should offer more resources and services to provide women and families with more options that can enable women to strike a balance between childcare and work. For the long term, to reduce the impact of child-bearing/raising on career development, young couples have tried a variety of approaches. Some women would give up their jobs; while others turn to more flexible irregular employment or self-employment.For example, according to the research findings in Jiangsu province, women’s formal employment had an adverse effect on their intentions to have a second child. More specifically, women who worked at state-owned enterprises, collectivelyowned enterprises, or institutions of other categories were less likely than women in other occupations(self-employed women, private entrepreneurs,unemployed housewives, agricultural laborers,etc.) to have a second child.①Zheng et al., 2009In terms of time arrangement, the above two groups of women were categorically different. The first group of women had a more fixed working timetable, which could not be easily re-adjusted according to individual or family needs while the second group enjoyed more freedom in arranging their work. It needs to be pointed out that both unemployment and irregular employment can plunge women into a disadvantageous situation featuring lower income, lack of labor security and uncertain career prospects. In a society whose labor security system still needs improving, such a disadvantageous situation is particularly highlighted.According to research findings in South Korea,women who temporarily quit work for child-birth could hardly maintain their previous professional status for a new job, unless they resumed their work as soon as possible; the longer a career interval was,the more difficult it was for women to find a new job corresponding to their previous career achievements;those who had an urgent need to be re-employed to increase family income had no choice but to accept a lower-ranking job.

A childcare-friendly employment environment can benefit men, as well as women who strive to balance career development and family life.The re-division of labor within a family and the enhancement of the father’s role in childcare requires support from society, workplace and public policy. In this regard, there are many international practices, experiences and lessons to be learned. Take Japan as an example. The Japanese government introduced childcare services and a“child allowance,” which, however, have so far failed to boost substantial progress in balancing career development and family life. There are two reasons for this failure. First, Japanese men can only enjoy a very short paternity leave; second, Japanese men were concerned about the possible negative impact of paternity leave on their future pay-rise and job promotion. Another example is South Korea, which did not provide sufficient benefits for professional women, nor create any favorable environment for men to allow men to participate in childcare.①Kim & Zuo, 2017In China, with the extensive introduction of the“two-child policy” in recent years, all provinces(or rather, provinces, municipalities directly under the central government and autonomous regions)have introduced stipulations concerning father’s parental leave. According to the research findings of this paper, even if a father spends more time on childcare, he is not likely to effectively replace the mother’s role. Besides, there is a lack of necessary encouragement and support for father’s childcare in our current society and workplace environments, for which the implementation effect of father’s parental leave remains to be seen and evaluated.

Given grandparents’ significant role in childcare,favorable policies (a more flexible retirement system, portable medicare benefits, etc.) should also be introduced to boost the grandparents’ childcare initiative. Such moves can bring the elderly’s childcare initiative into full play. Female labor force participation sees a drastic drop after Chinese women turn 50, which should be attributed to family factors (senior and child care), as well as the existing retirement system and enterprise restructuring.Nonetheless, as senior citizens attach more importance to health and postpone their retirement,working couples will probably lose the help from the elder generation. In that case, it will be hard for them to cope with the dual pressure of childcare and work by relying solely on family’s help. More outside support is needed.

In current China, changed family structure,increased family income and pursuit of quality personal/family life is in stark contrast with its lack of relevant policies and mechanisms which enable women to attach equal importance to child birth/care and career development. China’s easing of family planning may further increase the risk of young women’s withdrawing from the labor force market for childcare purposes. At present, it is imperative to establish and improve a corresponding support system to help young couples pursue career development while at the same time do their fertility planning as they wish. Whether it is from the perspective of population, economy or society,government-led efforts in work-life balance and social support of childcare are of great significance.Effective public policies should be adopted to balance career development and childcare for women and their families. From a micro-perspective, this can help couples to realize their fertility intentions and promote family harmony. In a larger sense, it will help China avoid the continuation of negative population growth (NPG) while maintaining the high working participation of the population,particularly young people. China should advocate a socially supportive environment, formulate support policies from a gender perspective, explore the government’s effective intervention and guidance,and encourage family members and social services to rationally share women’s childcare burdens to enable them to strike a balance between childcare and work.

This paper extends women’s childcare time to cover family’s help and replacement, strives to attract more attention from society (policy-makers in particular) regarding men’s participation in housework and childcare, and gives full credit to grandparents’ crucial role in childcare, instead of focusing solely on mothers’ duties. So far, this issue has not been paid due attention, thoroughly studied,or supported with appropriate data. The existing surveys tended to primarily target women, children or the elderly, without caring about the relationships among members of a family (not necessarily family members living under the same roof), making it impossible to access information in an all-round way. Take the two sets of data used in this paper as an example. The first set did not cover grandparents’time spent on childcare; while the second set lacked information on father’s participation in childcare.Because of that, this paper can only piece together a relatively complete childcare picture. There are some investigations and surveys confusing housework hours with (child and elderly) care hours, thus affecting the accuracy of childcare time analysis.It is hoped that more attention can be paid to this area and that more information, collected through special surveys and investigations, can be available to facilitate in-depth analysis and thereby offer more empirical support for related decision-making and public service design.

杂志排行

Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- The Historical Development of Literary Anthropology in China

- Cultural Structure of Solar Terms and Traditional Festivals

- The Development of China’s Intellectual Property Law over the Past Forty Years of Reform and Opening Up

- The Evolution, Characteristics of Poverty and the Innovative Approaches to Poverty Alleviation

- Social Security Internationalization During China’s Reform and Opening Up from 1978 to 2018— Viewed from the Paradigm of a Community with a Shared Future for Mankind

- Pattern of Opening Up, Integration and Reshaping Economic Geography—A New Economic Geography Analysis of the Belt and Road Initiative and the Yangtze River Economic Belt