A cross-sectional study to assess the out-of-pocket expenditure of families on the health care of children younger than 5 years in a rural area

2018-10-16SaurabhRamBihariLalShrivastavaPrateekSaurabhShrivastava

Saurabh RamBihariLal Shrivastava , Prateek Saurabh Shrivastava

Abstract Objective: This study aimed to estimate the out-of-pocket expenditure of families on the health care of children younger than 5 years in a rural area of Kancheepuram district.Methods: A cross-sectional descriptive study was performed in a rural area of Kancheepuram district for 5 months. All households with at least one child younger than 5 years were eligible for the study, and 153 households were selected for the final study. A semistructured and pretested schedule was used to obtain information about various study variables during home visits. Ethics approval was obtained before the start of the study. Data were entered into Microsoft Excel, and statistical analysis was done with IBM SPSS Statistics version 23. Frequency distributions were calculated for all the variables.Results: The findings indicate that most children younger than 5 years were males (62.7%).The maximum out-of-pocket expenditure was for accidents/trauma and in cases of fever/malaria.Further, 96 households (53.1%) preferred private-sector health care for their ailments.Conclusion: The findings indicate that 93 of the children younger than 5 years (60.8%) had experienced one episode of illness in the previous 3 months. Further, the maximum out-of-pocket expenditure was for accident/trauma cases, and overall the largest share was for buying medications for the treatment.

Keywords: Out-of-pocket expenditure; health; rural.

Introduction

Disease and ill health not only affect individuals by interfering with the quality of life but also affect their families by disturbing the balance between income/income generation and expenditure [ 1]. Over the decades,a direct association has been observed between poverty and poor health standards, especially in low-resource settings [ 2].Even relatively small monetary expenditure on health care can jeopardize poor households as most of their financial resources are used for basic needs and thus they are less able to cope with any unexpected expenditure [ 3]. Out-of-pocket(OOP) expenditure on health care refers to any direct expenses by the households (including gratuities and in-kind payments)toward the payment of medical bills or for medicines/therapeutic appliances and other goods and services to restore the health status of an individual [ 4 – 7].

The Government of India has adopted a tax-based model for financing health care in the entire nation [ 1, 8]. However,the limited amount the nation’ s gross domestic product spent on health care, the absence of a risk-pooling mechanism in the health financing systems, and constraints in public health infrastructure (viz., accessibility to health centers, geographical disparity, nonenrollment of health staff – vacant posts, untrained staff, limited outreach activities, poor quality of health care,rigid timings, interrupted supply of drugs, insensitive nature of health workers toward patients, poor communication skills of health workers, etc.) have forced people to seek private health care for their ailments [ 6, 9 – 11]. Further, the findings of the National Sample Survey indicated that in excess of 85.0% of the rural population was not covered under any health expenditure support scheme, and that for them the main source for health expenditure is either income/savings or borrowed money [ 12].

Although the private sector neutralizes most of the deficiencies of the government health setup, people have to pay a price for restoring their health by incurring high OOP expenditure [ 13]. Even though studies have been conducted to assess the OOP expenditure in heterogeneous settings of the nation [ 1, 4, 13], no such study has been performed in a rural area of southern India. Thus, the present study was conducted with the objective to estimate the OOP expenditure of families on the health care of children younger than 5 years in a rural area of Kancheepuram district.

Materials and methods

Study design, area, and sampling technique

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study that lasted 5 months (September 2017 to January 2018) conducted in the village of Sembakkam, as it is the rural field practice area of the medical college and is readily accessible. A universal sampling method was used.

Study participants

The study participants were children younger than 5 years but the information pertaining to the study was obtained from their parents.

Sample size

The sample size was 153. Estimates from the Sembakkam Primary Health Centre revealed that almost 187 families residing in the study area have a minimum of one child younger than 5 years; however, their eligibility for the study was considered on the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were families with a minimum of one child younger than 5 years, residing in the study area, and with a history of at least one episode of illness/sickness in the child younger than 5 years in the previous 3 months, and willingness of the informant to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Children younger than 5 years who had experienced no episodes of any illness/sickness in the previous 3 months were excluded from the study to minimize recall bias. Families that could not be contacted on three consecutive visits spread over a period of 2 weeks were also excluded. In addition, informants not willing to participate in the study were also excluded.

Data collection instrument

A semistructured and pretested schedule (developed on the basis of the questionnaire used in similar studies in Indian settings) [ 1, 13] was used for data collection.

Study variables

The study variables were the sociodemographic characteristics of the family, the number of illness episodes and the nature of the illness, the status of the treatment obtained and its source, and OOP expenditure under different categories(consultation, medicines, transport, hospitalization, and others such as communication, laboratory investigations, and charges for meals).

Method

A home visit was made to each of the identified families with a minimum of one child younger than 5 years. Only those families with a history of at least one episode of illness/sickness in the previous 3 months among children younger than 5 years were included in the final study. The informants were interviewed face-to-face with the help of a semistructured schedule after their written informed consent had been obtained.Information pertaining to the sociodemographic profile,type of health problems the children had experienced in the 3 months preceding the study, where treatment was sought, the reasons for the treatment, and the amount paid for the treatment was obtained from the selected families. However, for the families that could not be contacted at the first visit, two more attempts were made to contact the family members during the next 2 weeks. The socioeconomic class of the families was ascertained with the modified Prasad classification [ 14].

Operational definition

OOP expenditure is defined as any direct expenses of the families toward the payment of medical bills or for medicines/therapeutic appliances and other goods and services (viz.,laboratory investigations, radiological investigations, etc.) to restore the health status of the sick child. It also includes any other expenditure during the episode of illness, such as transport expenses, telephonic communications, and charges for meals or stay, and loss of wages.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee before the start of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents before any information was obtained from them. Utmost care was taken to maintain privacy and confidentiality.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into Microsoft Excel, and statistical analysis was done with IBM SPSS Statistics version 23. Frequency distributions were calculated for all the variables.

Results

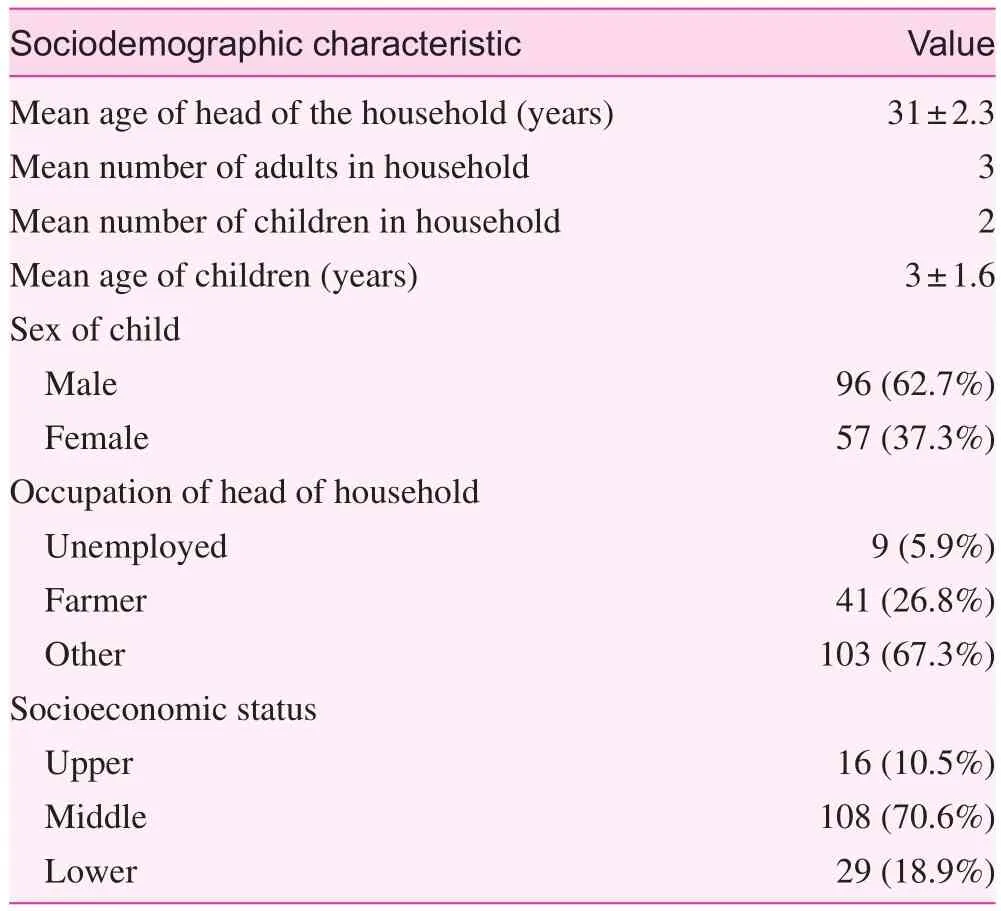

Table 1 reports the various sociodemographic characteristics of the children younger than 5 years. Most of the children were males (62.7%), and most of the heads of the households (103,67.3%) were employed in nonagricultural work. Further, of the 153 children included in the study, 93 (60.8%) had experienced at least one episode of illness, while the remaining 60(39.2%) had experienced two episodes of illness in the previous 3 months. Also, 7 (4.6%) of the children had experienced more than two episodes of illness in the previous 3 months.

Table 2 reports the distribution of OOP expenditure on the basis of different types of illness that were reported in the children younger than 5 years in the previous 3 months.Among all the illnesses, 63 episodes of respiratory tract infections were reported (28.1%), followed by 45 episodes of fever(20.1%). Accidents/trauma accounted for the maximum average expenditure of INR 1146, followed by INR 430 for cases of fever/malaria. Further, for children with respiratory tract infections and diarrhea, INR 301.3 and INR 201.2, respectively, had to be spent for the treatment of their illnesses.

Table 3 reports the total OOP expenditure of households for the treatment of their children younger than 5 years depending on the type of health facility approached. Overall, 38 households used only a government health facility for treatment,64 households used only a private health facility for treatment, and 23 households used only another source of health treatment. On the other hand, 28 households tried different combinations either for the same episode of illness or for two different episodes. On average, each household spent a total of INR 131.1 for treatment in a government health facility, INR 709 for treatment in a private health facility, and INR 130.6 for treatment by other means (traditional healers, pharmacy,self-medication, etc.). When households were asked why they visited private hospitals even though they have to spend more than six times the average cost in government hospitals,more than 70.0% of the informants stated that the government health staff do not show compassion and that government hospitals have rigid timings, which prevent them from obtaining timely care. Further, almost 19 households (19/153 = 12.4%)preferred self-medication for the ailments of their children younger than 5 years.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants

Table 2. Out-of-pocket expenditure based on episodes of illness among children younger than 5 years in the previous 3 months

Table 3. Out-of-pocket expenditure based on type of health facility approached

Table 4 shows the various categories for which the families had to spend money for the treatment of the illnesses in their children younger than 5 years in the previous 3 months. In boththe outpatient department and the inpatient department of the government health facilities, the maximum OOP expenditure was on buying medicines (average 63.8%), which were not available free of charge. Even in the private sector, the major proportion of OOP expenditure was on buying medications(average 46.4%). In addition, a significant amount of direct/indirect expenditure in areas such as travel, food, telephonic communications, and stay, and loss of daily wages (more in government facilities than in private facilities) was also observed in the both government sector and the private sector.

Table 4. Categories for out-of-pocket expenditure (INR)

Discussion

The present study was conducted among 153 children younger than 5 years residing in a rural area of Kancheepuram district to estimate the OOP expenses for various ailments in the previous 3 months. Overall, 93 children (60.8%) had experienced at least one episode of illness, while the findings obtained from a study done in the Anganwadi centers in the urban area of Puducherry revealed that at least 30.0% of the registered beneficiaries had experienced one episode of illness in the previous 3 months [ 15]. The lower rates of episodes of illness in the Puducherry study could be because the study was conducted within an institutional setup (and was not a community-based study), and thus many of the children younger than 5 years who became sick (but were not enrolled in Anganwadi centers) during the study period in the area might have not been included. In addition, the findings of a cross-sectional survey done in Bangladesh using a pretested structured questionnaire reported that at least 50.0% of the children younger than 5 years reported an illness in the preceding 2 weeks [ 16].In the current study, respiratory tract infections were the most common infection among the children younger than 5 years (28.1%). However, in a study done among children younger than 5 years in a semiurban area of Tanzania, fever,cough, and diarrhea were the most common morbidities [ 17].Similarly to our study, respiratory illnesses were found to be the leading morbidity in cross-sectional studies done in southern India (27.0%) and rural settings of Maharashtra(36.0%) [ 15, 18]. Furthermore, the findings of a study done in Pakistan revealed that diarrheal episodes were most common among children younger than 5 years [ 19]. The reported heterogeneity in the pattern of diseases could be due to seasonal variations or the study settings – institutional or community based.

Further, in the present study, most OOP expenditure was for treatment of accidents/trauma (26.0% of total OOP expenditure) and treatment of fever (24.4% of total OOP expenditure). In a study done in Pakistan, the majority of the out-of-pocket expenditure was on the treatment of illnesses like malaria, fever and diarrhea [ 20]. The reported variability in OOP expenditure could be due to either inflation or variable study settings or even local government policies, which may or may not advocate provision of free services.

Our study showed that most of the households (96, 53.1%)preferred a private health facility for the treatment of the ailments of their children younger than 5 years. It is quite alarming that even though most of the health services offered in the state are free of cost, most people preferred the private sector. The findings of a study done in a slum population of Karnataka also revealed that private practitioners were the major health providers in that setting for the treatment of children younger than 5 years [ 1]. The variable proportion between different studies is due to the study settings, recall periods, and age profile.

Moreover, our study reflected that approximately 86.2% of the households availed themselves of care from trained health personnel, while the remaining households used either a pharmacist or self-medication or did not opt for treatment. In contrast, the findings of the cross-sectional survey in Bangladesh indicated that only 14.0% of households availed themselves of care from trained health personnel [ 16]. This could be due to the educational status of the parents, and the quality of the health care delivery system in the area. The educational status of the mother has been identified as the key factor in determining the preferred type of health care facility as evidenced in the cross-sectional studies done in Bangladesh and Pakistan [ 16, 19].

In addition, the present study showed that the people who availed themselves of health care in the private sector had to pay 9.6 times more than those who availed themselves of health care in the government sector. Similar trends were reported in a case-control study done in Tanzania (six times higher cost in the private sector) [ 17]. These findings are quite obvious as the private sector works with the notion to earn money and thus levies heavy charges on its patients.

Similarly to our study, the findings of the study done in Puducherry reflected that the services offered in the government sector (outpatient and inpatient departments) are free of cost [ 15]. Nevertheless, the major expenditure in the government sector in the current study was on buying medications (which are not available in the government setup) and on investigations such as CT scans. The findings of different studies have shown that the maximum proportion of OOP expenditure is on buying medicines [ 15, 21]. In accordance with our study findings, many studies have shown that to meet health care costs, most people had to spend out of their own pocket, while many either borrowed money from relatives or friends or sold a household item [ 19, 21].

The strength of the current study is that it focuses on an important public health perspective and that it was conducted in a community setting instead of an institutional setting.However, the study had some limitations, such as potential recall bias, and the consequence of OOP expenditure on the households was not assessed.

Conclusion

The findings from the study indicated that 93 (60.8%) of the children younger than 5 years had had experienced one episode of illness in the previous 3 months. Of the total OOP expenditure, 86.0% was by people who availed themselves of health care from the private sector. Further, the maximum OOP expenditure was for accident/trauma cases, and overall the largest share was for buying medications for the treatment.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

SRS contributed to this work through the conception or design of the work, data collection, statistical analysis, drafting of the manuscript, and approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed on all aspects of the work.

PSS contributed to this work through the literature review,statistical analysis, revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed on all aspects of the work.

杂志排行

Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Number, distribution, and predicted needed number of general practitioners in China*

- The role of the teaching practice in undergraduate medical education:A perspective from the United States of America

- Integrated primary care– behavioral health program development and implementation in a rural context

- Blood pressure– controlling behavior in relation to educational level and economic status among hypertensive women in Ghana

- Development and validation of the Mothers of Preterm Babies Postpartum Depression Scale

- Factors influencing IOP changes in postmenopausal women