Chinese Stories in Traditional Paintings

2018-08-06byYuGe

by Yu Ge

In the early 1940s, Zhang Daqian (1899-1983), one of the most famous traditional painters in modern China, spent nearly three years copying murals preserved in the Buddhist grottoes in Dunhuang, in Chinas northwestern province of Gansu. In 1944, he held an exhibition in Chengdu, capital of Sichuan Province, to display what he copied. Among the visitors was a 10-year-old boy, who still has a brochure from the exhibition.

The boy was Jiang Ping, who was born into a family of calligraphers and painters. His father, Jiang Fanzhong, was a friend of Zhang Daqian. Three years later in 1947, Jiang Ping became Zhangs youngest student.

Over the past seven decades, Jiang Ping has continuously absorbed Zhangs painting techniques while exploring his own style, eventually reaching the status of a painting master of Sichuan. In May 2018, 84-year-old Jiang Ping held a solo exhibition at the“China Treasures” art gallery in Beijing Hotel, displaying over 120 paintings he finished over the past 20 years.

On appreciating traditional Chinese art, Jiang told visitors:“Traditional Chinese painting is like embroidery—both need to be carefully examined to find their hidden meaning.”

Silent Mountains, Glassy Ponds

Traditional Chinese painting is popularly referred to as “ink-wash Danqing.” In fact, “Danqing” refers to heavy colors such as cinnabar and turquoise used in art creation. Therefore, the name “ink-wash Danqing” not only includes references to two different coloring styles, but also represents two major genres of traditional Chinese art: ink-washing painting and realistic heavy-color painting.

Zhang Daqian was dubbed the“Eastern Brush” by many in Western art circles. Many of his works integrate realistic and freehand styles. Jiang Ping inherited this strategy and is particularly proficient in realistic painting. His exhibition in May displayed both ink-wash and heavy-color paintings involving subjects like flowers, birds, landscapes, animals and insects, fusing humor with solemnity.

In contrast to freehand painting featuring rough and simple lines with focus on setting the mood, realistic painting requires drawing details with exquisite, meticulous strokes similar to classical Western oil painting.

Perhaps this is why Jiang Ping likened traditional Chinese painting to embroidery: both require painstaking meticulousness. “Realistic painting is time-consuming, and each piece of work could take more than a month to complete,” he said.

Moreover, traditional Chinese painting is often accompanied by calligraphy, poetry and seals, which enrich the artistic value of the painting. Jiang Ping believes that “poetry is music to painting, and painting is dance to poetry.” He often selects a poem before beginning a painting and likes to write meaningful verses that eulogize virtues and good character on his paintings. According to Li Yansheng, a former researcher at the Palace Museum, Jiang Ping inherits Zhang Daqians style that retains the core value of traditional Chinese scholarly painting.

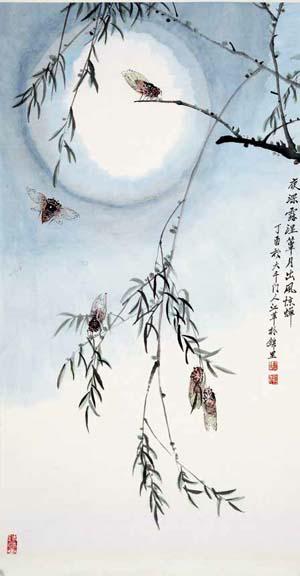

“Jiang Cicada” and “Jiang Fan”

Jiang Pings paintings depict a wide array of subjects including flowers, birds, fish and insects. He is so noted for his cicada paintings that he was nicknamed “Jiang Cicada.”A painting depicting cicadas in the moonlight was particularly popular at the exhibition. In the painting, five lifelike cicadas flying or perching on willows bathed in the moonlight create a poetic ambiance.

In traditional Chinese culture, the cicada symbolizes nobility and moral integrity, so its a popular subject for many painting masters.

Jiang Ping began to draw cicadas in the 1980s. After careful research of cicada paintings from past dynasties, he concluded that few of those works devoted much detail to the insects wings and some even incorrectly depicted its body structure. Accurately representing the cicadas body structure and vividly depicting its thin, transparent wings became Jiangs mission. Over the next several years, he collected cicadas from the wilderness, made specimens and studied their bodies carefully. “Just like Qi Baishis depictions of shrimp, I apply the thickest stroke before the ink dries,” Jiang revealed. “This is how I clearly depict the veins on their wings.”

According to senior Chinese collector Li Baojia, Jiang Pings cicadas differ from those of his teacher Zhang Daqian. “Jiangs cicada paintings are more meaningful and convey profound traditional Chinese culture.”

Along with cicadas, Jiang Pings work on fans is also outstanding. Many of his painted fans are on display at the exhibition as well. Chinese fan culture has a long history. As early as the 18th century, Chinese fans were introduced to Europe via the Silk Road and gained popularity with the upper class of the West. After centuries of evolution, fan painting and calligraphy have become icons of classical Chinese culture.

Jiang had already become passionate about fan painting and calligraphy by a young age. So far, he has created more than 1,000 pieces of one or the other. He integrated and absorbed highlights of other artists to form a distinctive fan painting style after further exploring the aesthetic and visual effects of color brushwork. He once published a collection of fan paintings, for which famous Chinese art critic Liu Chuanming wrote in the preface:“Painting on fans, especially folding fans, requires not only following the curves of the fan to fill the space but also realistic techniques to draw the emptiness. Jiang Ping performs exceptionally well in both regards, so his fan paintings are imbued with an archaic touch and preserve orthodox styles of traditional fan painting.”

Bond with “China Treasures”Art Gallery

The host of the 2018 exhibition, the “China Treasures” art gallery in Beijing Hotel, is located adjacent to Tiananmen Square, the Palace Museum and Wangfujing Pedestrian Street. Li Jing, founder of the gallery, formerly worked with civil aviation companies and media organizations which left her with rich experience in management and investment. She has been committed to the protection and inheritance of traditional Chinese culture for many years. In 2008, she founded the art gallery to promote and collect precious art created by state-class masters that are considered“national treasures.”

Li Jing was impressed when she first saw Jiang Pings work. “Many senior artists spend all of their time painting rather than promoting their art,” she explained. “But their works are very impressive. What kinds of Chinese stories are worth hearing? I prefer stories from senior artists who have inherited traditional culture.”

Along with traditional calligraphy and paintings, the art gallery has also collected more than 100 pieces of cloisonné and carved lacquerware. Both crafts were part of the first group of Chinese intangible cultural heritage. Many art and crafts masters have established cooperative relations with the art gallery including contemporary Chinese carved lacquerware master Man Jianmin and cloisonné master Xiong Songtao.

During Jiang Pings painting exhibition, the art gallery organized several events themed around traditional Chinese culture to accent traditional Chinese painting with performances of guqin (a traditional seven-stringed plucked instrument) and tea ceremonies. On June 9, 2018, Djoomart Otorbaev, former prime minister of Kyrgyzstan, visited the art galley and showed great interest in traditional Chinese calligraphy, painting and royal treasures. He pointed out how special Chinese culture is and how much of it cannot be found in any other country. He also expects more excellent Chinese cultural achievements to begin being exported.