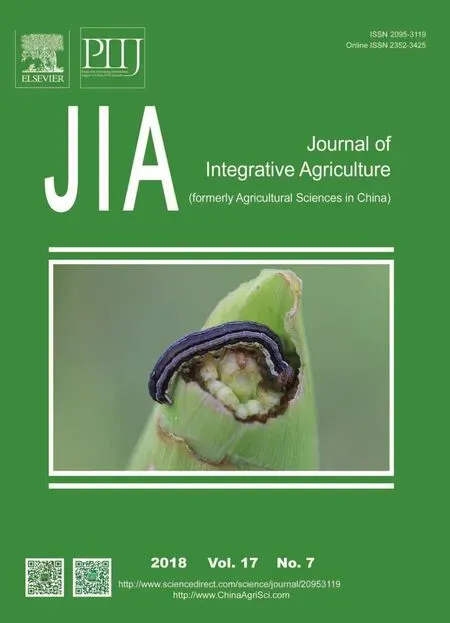

Effects of temperatures on the development and reproduction of the armyworm, Mythimna roseilinea: Analysis using an age-stage,two-sex life table

2018-07-09QlNJianyangLlUYueqiuZHANGLeiCHENGYunxiaLUOLizhiJlANGXingfu

QlN Jian-yang , LlU Yue-qiu, ZHANG Lei, CHENG Yun-xia LUO Li-zhi JlANG Xing-fu

1 State Key Laboratory for Biology of Plant Diseases and Insect Pests, Institute of Plant Protection, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100193, P.R.China

2 College of Plant Science and Technology, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan 430070, P.R.China

3 College of Landscape Architecture, Beijing University of Agriculture, Beijing 102206, P.R.China

1. lntroduction

The Mythimna roseilinea (Walker), an armyworm found in China, Sri Lanka, Singapore, Malaysia, India, Myanmar,Japan and the Philippines (Luo et al. 1981), is an emerging pest of grain crops in South China. Particularly, it frequently co-occurs with a closely related species, the oriental armyworm, Mythimna separata (Walker), a notorious polyphagous pest of grain crops in China that annually inflicts huge economic losses nationwide (Jiang X F et al.2014; Jiang Y et al. 2014). The biology of M. separata is well documented in China (Li et al. 1964; Jiang et al. 2011),however, little is known about M. roseilinea biology, making it difficult to predict its population dynamics and to develop management strategies. The two species are highly similar in morphology at larval and pupal stages and are difficult to distinguish, previous studies have suggested that their life history and behavior are significantly different (Luo et al. 1981). Therefore, population projections for the two armyworms are probably different.

Environmental factors, including temperature, affect insect population dynamics by influencing development,survival, and fecundity (Logan et al. 2006; Broufas et al. 2009; Forster et al. 2011). Optimal environmental temperature allows rapid development and reproduction of insects, while temperatures above or below this range can have adverse effects (Zhou et al. 2010; Regniere et al. 2012). High temperatures reduce the development,survival, longevity and fecundity of M. separata (Jiang et al. 1998, 2000), and similar results have been found in other insect species including Bemisia tabaci type B (Guo et al. 2013), Sitophilus granarius (Mourier and Poulsen 2000), Harmonia dimidiata Fabricius (Yu et al.2013), Ophraella communa LeSage (Zhou et al. 2010) and Scymnus subvillosus Goeze (Atlihan and Chi 2001). Low temperatures hinder insect population growth, because each life stage requires a certain threshold temperature to complete development, and an entire generation requires sufficient effective accumulated temperatures which are commonly measured as degree-days (Ma et al. 2008).Therefore, knowledge of lower threshold temperatures and effective accumulated temperatures can be used to accurately predict an insect’s period of occurrence and to determine the optimal timing of control (Wu et al. 2003).

The life table is a powerful and necessary tool for analyzing the effects of environmental factors on insect survival, growth, development and reproductive capacity.This information is critical to predicting population dynamics(Chi and Su 2006), guiding insect mass-rearing (Chi and Getz 1988), and understanding the consequences of host preference on fitness (Yin et al. 2013). There are several standard methods for constructing a life table, most notably the traditional female age-specific life table and the age-stage, two-sex life table. Unlike the former, the agestage, two-sex life table approach accommodates variable development times among individuals, which usually have overlapping stages. Furthermore, this type of life table can deal with survival and fecundity properly and takes sex ratio into account, so it is more powerful in the analysis of population development (Chi 1988). Thus, population growth of insects can be accurately projected using this approach (Chi 2016b). This method has been applied to many insect pests including whiteflies (B. tabaci; Jafarbeigi et al. 2014), lepidopterans (Chrysodeixis chalcites; Alami et al. 2014; Spodoptera litura; Tuan et al. 2014), thrips(Frankliniella occidentalis; Zhang T et al. 2015), and mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus and A. aegypti; Maimusa et al. 2016), and others.

In this study we used the age-stage, two-sex life table approach to compare the development and population growth of M. roseilinea reared at five different temperatures.The information will be beneficial for understanding how temperature affects the population dynamics of this pest species and for predicting and managing negative impacts of M. roseilinea.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. lnsect source and rearing

Old larvae of M. roseilinea were collected from rice field in Nanning City, the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region,China, in March 2014 and maintained under laboratory conditions at (24±1)°C, (70±5)% relative humidity (RH),and a photoperiod of 14 h L:10 h D. Ten larvae were reared together in 700-mL glass bottles (14 cm high by 8 cm diameter) on fresh corn leaves cultivated in laboratory of the Institute of Plant Protection, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. They pupated in sterilized soil with a moisture content of approximately 10–15%. When adults emerged,the moths were reared in pairs in an insect cage (21 cm high by 9 cm diameter, 1 200 mL capacity) and provided a cotton ball soaked with 5% honey (v/v) water solution.Folded waxed paper was placed on the bottom of the cage for egg-laying. Eggs laid on the second day of oviposition were selected for experiments. We began the experiments after five generations of laboratory rearing.

2.2. Experimental design

We collected waxed papers and cut them into pieces containing 30 eggs each. Three replicates of 30 eggs(90 total) were placed in 700-mL glass bottles with fresh corn leaves (corn variety: Nongda 108) and held in growth chambers (RXZ-430, Jiangnan Ningbo Instruments, China)at 18, 21, 24, 27, and 30°C at 70% RH under a photoperiod of 14 h L:10 h D. An extra set of insects was reared in parallel at each temperature to provide supplementary males for mating if needed. Egg survival rate and the time to hatch at each temperature treatment were recorded. After hatching, larvae were reared in groups of 10 per 700-mL glass bottle on fresh corn leaves until pupation. Food was replaced daily. The number of surviving larvae was recorded each day, and the duration of the larval developmental period from hatching to pupation was noted. Pupal survival was calculated based on the number of emerging adults. Female and male adults that emerged on the same day from a given temperature treatment were paired and placed in the insect cages. If the number of emerging males was less than that of females, additional males from the extra set run in parallel were used to ensure each female was paired. Cages were provided with wax paper for oviposition, and 5% honey solution for adult feeding, both replaced daily. Numbers of eggs laid per female and adult mortality were recorded daily until all adults died.

2.3. Life table approach

2.4. Low threshold temperature and effective accumulated temperature

Data from the life table included time for all eggs to hatch,time for all larvae to develop into pupae, duration of the pupal stage, and female pre-oviposition period under each constant temperature. The effective accumulated temperature (K) and the lower temperature threshold temperature (C) were calculated according to the following equations:

Where, Tiis the experimental temperature and Diis the developmental duration (Li and Wang 1986).

2.5. Data analysis

Raw data for developmental duration, survival rate, longevity and female daily fecundity were analyzed according to the agestage, two-sex life table theory (Chi 1988) using the computer program, TWOSWX-MSCHART (Chi 2016a). The parameters of sxj,lx, fx, mx, r, λ, T and R0were calculated using the bootstrap method (Efron and Tibshirani 1993) included in the computer program TWOSWX-MSCHART. Because bootstrap analysis uses random resampling, a small number of replications will generate variable means and standard errors. To reduce variability of the results, 100 000 bootstrap iterations were run. The differences among the five temperature treatments were analyzed by the paired bootstrap test. Linear regression of developmental rate at each stage on rearing temperature was calculated using the SPSS 16.0.

3. Results

3.1. Development time, adult longevity and fecundity

Development time of each stage, adult longevity, preoviposition period, generation time, and female fecundity of M. roseilinea are presented in Table 1. According to the paired bootstrap test, development time of each stage,including egg (F4,10=79.7, P<0.001), larva (F4,10=71.7,P<0.001) and pupa (F4,10=30.9, P<0.001), was significantly affected by temperature. Likewise, adult pre-oviposition period (F4,10=30.9, P<0.001), adult longevity (Female F4,10=13.1, P=0.001; Male F4,10=10.5, P=0.001) and fecundity(F4,10=198.6, P<0.001) were also significantly affected by temperature (Table 1). The developmental time of each stage, pre-oviposition and longevity decreased as the temperature increased from 18 to 30°C. For the same temperature treatment the adult longevity of males was significantly longer than that of females (18°C: t=–3.69 df=35, P=0.001; 21°C: t=–3.02 df=51, P=0.004; 24°C:t=–7.04 df=52, P<0.001; 27°C: t=–5.73 df=46, P<0.001;30°C: t=–6.24 df=33, P<0.001). Both the mean fecundities of M. roseiline reared at 21 and 24°C were significantly higher than those reared at other temperatures.

Table 1 Developmental time, adult longevity and fecundity of Mythimna roseilinea reared at different constant temperatures

3.2. Age-stage-specific survival rate (Sxj)

The age-stage curves indicated the probability that an egg will survive to age x and develop to stage j (Fig. 1).Because the age-stage, two-sex life table takes into account variable developmental rates among individuals, there were overlaps in the survival curves between the stages. Female adults emerged earlier than male adults and had a shorter lifespan. M. roseilinea was able to complete its growth and development under all five temperatures tested. All eggs survived at any of the five temperatures tested (i.e.,survival rate=1.0). The lowest survival rate for larva and pupa occurred at 18°C (42.2 and 41.1%, respectively) and their highest survival rate was observed at 24°C (62.2 and 60.0%, respectively).

3.3. Age-specific survival rate (lx), female age-specific fecundity (fx), total population age-specific fecundity(mx), and age-specific maternity (lxmx)

Fig. 2 showed the lx, fx, mx, and lxmxof M. roseilinea reared at different temperatures. The lxcurve is a simplified version of sxj(Fig. 1) as it ignores differences among individuals. At each of the five temperatures tested, the lxcurve smoothly declined during the earlier life stages, indicating that the early egg mortality rate was relatively low. However, lxcurve declined sharply during the earlier stage of larva, suggesting higher mortality occurred in the lower instar stadium larva.The curve for the female fx, showing the number of eggs laid per female, reached the peak value at 24°C, likewise,mxpeaked at 24°C, contributing to the highest age-specific maternity (lxmx) observed at 24°C.

3.4. Population life table parameters

Table 2 presented the age-stage, two-sex life table parameters of M. roseilinea reared at different temperatures.Both r and λ increased significantly as the temperature increased. T decreased significantly with increasing temperature. The highest value of the net reproductive rate (R0=99.8 offspring individual–1) was recorded at 21°C but was not significantly higher than the value recorded for the 24°C treatment. The highest intrinsic rate of increase(r=0.100 day–1), the highest finite rate of increase (λ=1.11 day–1) and the shortest mean generation time (T=31.4 day)were all recorded at 30°C. These results indicate that the population reaches the stable age-stage distribution and if there are no mortality factors other than physiological factors, the M. loreyi population could increase at 30°C by approximately 1.11 times per day for an average generation time of approximately 37.3 days, with an exponential rate of increase of 0.100 day–1.

3.5. Population projection

Based on the population life table parameters, the population size of different stages of M. roseilinea through the next generation was calculated (Fig. 3). The projected populated growth of a single release of 30 newly hatched M. roseilinea eggs over 60 days differed significantly between the five temperatures considered. The population can reach the second-generation pupa stage at 30°C, second-generation larva stage at 27°C, second-generation egg stage at 24°C,and they may not complete a single generation at 21 and 18°C during a 60-day period. The population size that was reared at 24°C showed the most rapid increase while reared on 18°C grew the slowest.

3.6. Lower threshold temperature and effective accumulated temperature

Linear regressions of the developmental rates of each stage on experimental temperature revealed significant correlation (Table 3), allowing calculation of lower thresholdtemperature and effective accumulated temperature. So the lower threshold temperature and effective accumulated temperature values of each stage were calculated (Table 4).The results demonstrated that the lower threshold temperature of the pupa was the highest (14.35°C) and pre-oviposition was the lowest (7.42°C) among different developmental stages, while the effective accumulated temperature of the larva was the highest (445 degree-days),accounting for 63.7% of the total generation total and that of egg was the lowest (63.59 degree-days).

Fig. 1 Age-stage-specific survival rate (sxj) of Mythimna roseilinea as affected by different temperatures.

4. Discussion

Temperature has significant effects on the population distribution, life history, behavior, and species abundance of insects (Hoffmann et al. 2003). In this study, we found that the developmental time and pre-oviposition period of M. roselilinea decreased significantly as temperature increased from 18 to 30°C. And the developmental time of larva and pupa were longer than that of M. separata at each same temperature, but pre-oviposition and adult longevity were quite similar between the two insects(Qin 2017). This makes it rather difficult to forecast their respective occurrence period in the field. Both male and female moth longevity decreased as temperature increased,and the longevity of male was longer than female moth.Similar results were also reported in M. separata (Lü et al.2014). The fecundity was the highest at 24°C but hasno significant difference at 21°C. Based on decreased developmental time to adulthood and increased female fecundity, the optimal range of temperatures for the growth and development of M. roseilinea is between 21 and 24°C.However, at all five rearing temperatures tested, larval mortality was the highest during the earliest, indicating that this larval stage is most vulnerable to environmental stress;thus, this is the ideal stage at which the insect population could be controlled. Likewise, the mortality was the highest for the 18°C treatment, the lowest tested temperature.This suggests that low temperatures are unfavorable for M. roseilinea survival, and may explain the fact that this

insect pest usually occurs and damages corn in South China in winter, where annual average temperature is above 18°C(Luo et al. 1981).

Table 2 Population parameters for Mythimna roseilinea at different rearing temperatures1)

r is a useful parameter for describing populationdynamics, which encompasses survival, development and reproduction, and λ can reveal the total population increase over a certain period of time (Farhadi et al. 2011). In this study, r and λ of M. roseilinea increased significantly as temperature increased. R0was the highest at 21°C but not significantly different from that at 24°C. Survival rate for each stage and fecundity were the highest at 24°C. These results suggest that M. roseilinea populations would be the highest at 24°C, which may partially account for the high population density and associated crop damage of this armyworm in South China during October and November,when the average monthly temperature is approximately 24°C (Luo et al. 1981).

Table 3 Regressions of developmental rate of Mythimna roseilinea at each stage on rearing temperature

The lower threshold temperature and effectiveaccumulated temperature are necessary to forecast development time and the emergence period under ambient temperature, which can help to guide pest control decisions. Based on the 2015 mean annual temperature of Fujian (Wang 2016), we predicted M. roseilinea could occur 6.1 generations, which is consistent with six generations observed annually for natural populations in this province(Luo et al. 1981). In recently years, warm winters have become quite common in northern China, which may accelerate the life cycle of M. roseilinea. Age-stage, twosex life table population projection can reveal changes in the stage structure during population growth (Chi 1990).These data combined with the results generated from population projection and calculated effective accumulated temperature, will allow prediction of temporal dynamics of the armyworm and thus give suggestions for its management.

Fig. 3 Population projections over a 60-day period of Mythimna roseilinea reared at different temperatures,based on population parameters from an agespecific, two-sex life table analysis.

Table 4 Lower threshold and effective accumulated temperatures for indicated life stages of Mythimna roseilinea

In the present study, we uncovered the relationship between individual and population metrics of M. roseilinea and different temperatures under laboratory conditions.Our results are informative for the predicting of population dynamics and for determination of the time taking control measures. However, it should be noted that the population projections at constant temperatures under laboratory conditions are different from those under naturally fluctuating temperatures (Fischer et al. 2011). Many other factors such as food availability (Zhang P et al. 2015), light (Tu et al. 2014) and humidity (Yang et al. 2015) can also affect insect population projections. Therefore, these results should be strengthened with further investigation under natural conditions and it will be important to fully examine other key environmental variables as we attempt to build a practical framework for predicting population dynamics of M. roseilinea for practical applications.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we established the two-sex, age-stage life table of M. roseilinea at constant temperatures 18, 21,24, 27 and 30°C, and measured population parameters,including developmental duration, survival rate, fecundity,adult pre-oviposition period, total pre-oviposition period, r, λ,R0, population projection, lower threshold temperature and effective accumulated temperature. The results indicated that M. roseilinea has strong reproductive potential within 21–24°C, and that this temperature range could result in rapid population growth associated serious damage to grain crops at an appropriate temperature. Lower threshold temperature, effective accumulated temperature and life table population projection have practical significance for predicting the occurrence period and population abundance of the next developmental phase.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest of China (201403031),the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-22),the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0201802, 2017YFD0201701), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31672019,31371947) and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation,China (6172030).

Alami S, Naseri B, Golizadeh A, Razmjou J. 2014. Age-stage two-sex life table of the tomato looper, Chrysodeixis chalcites (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), on different bean cultivars. Arthropod-Plant Interations, 8, 475–484.

Atlihan R, Chi H. 2001. Temperature-dependent development and demography of Scymnus subvillosus (Coleoptera:Coccinellidae) reared on Hyalopterus pruni (Homoptera:Aphididae). Journal of Economical Entomology, 108,126–134.

Broufas G D, Pappas M L, Koveos D S. 2009. Effect of relative humidity on longevity, ovarian maturation, and egg production in the olive fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 102, 70–75.

Chi H. 1988. Life-table analysis incorporating both sexes and variable development rates among individuals.Environmental Entomology, 17, 26–34.

Chi H. 1990. Timing of control based on the stage structure of pest populations: A simulation approach. Journal of Economic Entomology, 83, 1143–1150.

Chi H. 2016a. TIMING-MSChart: A computer program for the age-stage, two-sex life table analysis. [2016-12-31].http://140.120.197.173/Ecology/Download/TIMING.zip

Chi H. 2016b. TWOSEX-MSChart: A computer program for the age-stage, two-sex life table analysis. [2016-12-31].http://140.120.197.173/Ecology/Download/TWOSEX.zip

Chi H, Getz W M. 1988. Mass rearing and harvesting based on an age-stage, two-sex life table: a potato tuber worm(Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) case study. Environmental Entomology, 17, 18–25.

Chi H, Liu H. 1985. Two new methods for the study of insect population ecology. Bulletin of the Institute of Zoology Academia Sinica, 24, 225–240.

Chi H, Su H Y. 2006. Age-stage, two-sex life tables of Aphidius gifuensis (Ashmead) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) and its host Myzus persicae (Sulzer) (Homoptera: Aphididae) with mathematical proof of the relationship between female fecundity and the net reproductive rate. Environmental Entomology, 35, 10–21.

Efron B, Tibshirani R J. 1993. An Introduction to the Bootstrap.Chapman and Hall, New York. pp. 49–54.

Farhadi R, Allahyari H, Chi H. 2011. Life table and predation capacity of Hippodamia variegata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae)feeding on Aphis fabae (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Biological Control, 59, 83–89.

Fischer K, Kölzow N, Höltje H, Karl I. 2011. Assay conditions in laboratory experiments: is the use of constant rather than fluctuating temperatures justified when investigating temperature-induced plasticity? Oecologia, 166, 23–33.

Forster J, Hirst A G Woodward G. 2011. Growth and development rates have different thermal responses.American Naturalist, 178, 668–678.

Goodman D. 1982. Optimal life histories, optimal notation, and the value of reproductive value. American Naturalist, 119,803–823.

Guo J, Cong L, Wan F. 2013. Multiple generation effects of high temperature on the development and fecundity of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) biotype B.Insects Science, 20, 541–549.

Hoffmann A A, Sørensen J G, Loeschcke V. 2003. Adaptation of Drosophila to temperature extremes: Bringing together quantitative and molecular approaches. Journal of Thermal Biology, 28, 175–216.

Huang Y, Chi H. 2012. Age-stage, two-sex life tables of Bactrocera cucurbitae (Coquillett) (Diptera: Tephritidae)with a discussion on the problem of applying female agespecific life tables to insect populations. Insect Science,19, 263–273.

Jafarbeigi F, Samih M, Zarabi M, Esmaeily S. 2014. Age stage two-sex life table reveals sublethal effects of some herbal and chemical insecticides on adults of Bemisia tabaci (Hem:Aleyrodidae). Environmental Entomology, 2014, 1–9.

Jiang X F, Luo L Z, Hu Y, 1998. Effects of high temperature on the immature stages of the oriental armyworm, Mythimna separata (Walker). Journal of Beijing University of Agriculture, 13, 20–26. (in Chinese)

Jiang X F, Luo L Z, Hu Y. 2000. Influences of rearing temperature on flight and reproductive capacity of adult oriental armyworm, Mythimna separata (Walker). Acta Ecologica Sinica, 20, 288–292. (in Chinese)

Jiang X F, Luo L Z, Zhang L, Sappington T W, Hu Y. 2011.Regulation of migration in the oriental armyworm,Mythimna separata (Walker) in China: A review integrating environmental, physiological, hormonal, genetic, and molecular factors. Environmental Entomology, 40, 516–533.

Jiang X F, Zhang L, Cheng Y X, Luo L Z. 2014. Current status and trends in research on the oriental armyworm Mythimna separata (Walker) in China. Chinese Journal of Applied Entomology, 51, 1444–1449. (in Chinese)

Jiang Y Y, Li G G, Zeng J, Liu J. 2014. Population dynamics of the armyworm in China: A view of the past 60 years research. Chinese Journal of Applied Entomology, 51,890–898. (in Chinese)

Li D M, Wang M M. 1986. Rapid development starting point estimates and effective accumulated temperature method research. Chinese Journal of Applied Entomology, 23,184–187. (in Chinese)

Li G B, Wang H X, Hu W X. 1964. Route of the seasonal migration of the oriental armyworm moth in the eastern part of China as indicated by a three year result of releasing and recapturing of marked moths. Journal of Plant Protection,3, 101–109. (in Chinese)

Logan J D, Wolesensky W, Joern A. 2006. Temperaturedependent phenology and predation in arthropod systems.Ecological Modelling, 196, 471–482.

Luo X N, Chen D Z, Zhang L X, Gan D Y. 1981. Study on the grain armyworm Leucania roseilinea Walker (Lepidoptera Noctuidae) in Fujian. Journal of Plant Protection, 8, 17–22.(in Chinese)

Lü W X, Jiang X F, Zhang L, Luo L Z. 2014. Effect of different tethered flight durations on the reproduction and adult longevity of Mythimna separata (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae).Chinese Journal of Applied Entomology, 51, 914–921. (in Chinese)

Ma L, Gao S, Wen J, Zong S, Xu Z. 2008. Effective accumulated temperature and developmental threshold temperature for Semanotus bifasciatus (Motschulsky) in Beijing. Forestry Studies in China, 10, 125–129. (in Chinese)

Maimusa H A, Ahmad A H, Kassim N F, Rahim J. 2016. Agestage, two-sex life table characteristics of Aedes albopictus and Aedes Aegypti in Penang Island, Malaysia. Journal of American Mosquito Control Association, 32, 1–11.

Mourier H, Poulsen K P. 2000. Control of insects and mites in grain using a high temperature/short time (HTST) technique.Journal of Stored Products Research, 36, 309–318. (in Chinese)

Regniere J, Powell J, Bentz B, Nealis V. 2012. Effects of temperature on development, survival and reproduction of insects: Experimental design, data analysis and modeling.Journal of Insect Physiology, 58, 634–647.

Qin J Y. 2017. The research of development, reproductive and flight activity among three kinds of sibling species of armyworm. MSc thesis, Huazhong Agricultural University,Hubei. (in Chinese)

Tu X Y, Chen Y, Zhi Y. 2014. Effects of light-emitting diode illumination on insect behavior and biological characters.Plant Protection, 40, 11–15. (in Chinese)

Tuan S, Lee C, Chi H. 2014. Population and damage projection of Spodoptera litura (F.) on peanuts (Arachis hypogaea L.)under different conditions using the age-stage, two-sex life table. Pest Management Science, 70, 805–813.

Wang S S. 2016. Fujian climate bulletin in 2015. [2017-01-12].http://www.weather.com.cn./tqyw/01/2444379.shtml (in Chinese)

Wu J J, Liang F, Liang G Q. 2003. Research on relationship between growth rate and temperature of Bactrocera dorsalis(Hendel). Inspection and Quarantine of Science, 13, 17–18.(in Chinese)

Yang Y T, Li W X, Xie W, Wu Q J, Xu B Y, Wang S L, Li C R,Zhang Y J. 2015. Development of Bradysia odoriphaga(Diptera: Sciaridae) as affected by humidity: An age-stage,two-sex, life-table study. Applied Entomology and Zoology,50, 3–10.

Yin W D, Qiu G S, Yan W T, Sun L N, Zhang H J. 2013. Host preference and fitness of Aphis citricola (Hemiptera:Aphididae) to mature and young apple leaves. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 24, 2000–2006. (in Chinese)

Yu J Z, Chi H, Chen B H. 2013. Comparison of the life tables and predation rates of Harmonia dimidiata (F.) (Coleoptera:Coccinellidae) fed on Aphis gossypii Glover (Hemiptera:Aphididae) at different temperatures. Biological Control,64, 1–9.

Zhang P, Liu F, Mu W, Wang Q, Li H. 2015. Comparison of Bradysia odoriphaga, yang and zhang reared on artificial diet and different host plants based on an age-stage, twosex life table. Phytoparasitica, 43, 107–120.

Zhang T, Reitz S R, Wang H H, Lei Z R. 2015. Sublethal effects of Beauveria bassiana (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) on life table parameters of Frankliniella occidentalis (Thysanoptera:Thripidae). Journal of Economic Entomology, 108, 975–985.

Zhou Z S, Guo J Y, Chen H S, Wan F H. 2010. Effects of temperature on survival, development, longevity,and fecundity of Ophraella communa (Coleoptera:Chrysomelidae), a potential biological control agent against Ambrosia artemisiifolia (Asterales: Asteraceae).Environmental Entomology, 39, 1021–1027.

杂志排行

Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- Characterisation of pH decline and meat color development of beef carcasses during the early postmortem period in a Chinese beef cattle abattoir

- Multi-mycotoxin exposure and risk assessments for Chinese consumption of nuts and dried fruits

- Effects of 1-methylcyclopropene and modified atmosphere packaging on fruit quality and superficial scald in Yali pears during storage

- Insertion site of FLAG on foot-and-mouth disease virus VP1 G-H loop affects immunogenicity of FLAG

- Update of Meat Standards Australia and the cuts based grading scheme for beef and sheepmeat

- Light shading improves the yield and quality of seed in oil-seed peony (Paeonia ostii Feng Dan)