Geochronological and geochemical constraints on the Cuonadong leucogranite,eastern Himalaya

2018-07-04JiajiaXieHuaningQiuXiujuanBaiWanfengZhangQiangWangXiaopingXia

Jiajia Xie•Huaning Qiu•Xiujuan Bai•Wanfeng Zhang•Qiang Wang•Xiaoping Xia

1 Introduction

Widespread leucogranites are a distinct feature of the Himalayan orogen formed by the collision between the Indian and Asian continents(Yin and Harrison 2000).These leucogranites are largely confined to two sub-parallel belts:The High Himalayan leucogranites(HHLs)and the North Himalayan granites(NHGs)(Fig.1a)(Harrison et al.1998).The HHL belt contains a discontinuous chain of sills,dikes and laccolithic bodies that intruded in the hanging-wall of the Main Central Trust(MCT)in the Greater Himalayan Crystalline Complex(GHC).The HHLs generally emplaced from 25 to 12 Ma(Guo and Wilson 2012).The NHG belt is composed of ellipticalshaped plutons that largely expose metamorphic cores of the North Himalayan domes in the Tethyan Himalayan Sequence(THS).The ages of most NHGs are 28 to 8 Ma(King et al.2011;Liu et al.2014),and several granites have formation ages ranging from 45 to 35 Ma(Aikman et al.2008;Zeng et al.2011;Liu et al.2016).Published ages for the Himalayan leucogranites are based on zircon,monazite,or xenotime U–Th–Pb dating;or muscovite or biotite40Ar/39Ar dating.It is worth noting that a majority of the NHG exposed in the core of gneiss domes is within the central THS,such as granites in the Malashan,Lhagoi Kangri,Sakya,Kampa,Kangmar,and Yala-Xiangbo gneiss domes.This special context of emplacement has caught the attention of many geoscientists focusing on the granites in the North Himalayan Gneiss Domes(NHGDs)to figure out the magmatic and tectonic processes involved in the genesis of these granites(Scharer et al.1986;Zhang et al.2004;Kawakami et al.2007;Lee and Whitehouse 2007;Murphy 2007;Aikman et al.2008;King et al.2011;Pullen et al.2011;Zeng et al.2011;Guo and Wilson 2012;Gao and Zeng 2014).

Fig.1 Simplified geologic map:a The Himalayan orogenic belt;b study area in the eastern Tethyan Himalaya

Field investigations have determined an undeformed intrusion of leucogranite exposed in the Cuonadong gneiss dome of the eastern Himalaya(Fig.1b).Compared with general NHGDs,the Cuonadong gneiss dome is exposed further south,adjacent to the South Tibetan Detachment System(STDS).In this study,we present new data of in situ Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry(SIMS)zircon U–Pb ages,40Ar/39Ar agesby laser stepwise heating,chemical compositions of major and trace elements,and Sr–Nd isotopes to investigate the formation age,source region,and mechanisms of the Cuonadong leucogranite.

2 Geologic setting and petrography

The Cuonadong gneiss dome is adjacent to STDS in the eastern Himalaya,cut by two normal faults with N–S and NNW trends(Fig.1b).The dome is located at the southern part of the Zhaxikang ore concentration area.Regionally,there are two groups of faults:oriented approximately E–W and N–S(Fu et al.2017).The dome has developed Barrovian-type metamorphism with grade increasing toward the granite core,like other NHGDs.The core of the dome consists of granitic gneiss and leucogranites cut off by many pegmatite veins.Zircons from the strongly deformed gneiss yield Early Paleozoic U–Pb ages of~ 500 Ma(Zhang et al.2017).The leucogranites display the characteristic of multistage intrusions,and Lin et al.(2016)reported that the early-stage muscovite granite crystallized around 21 Ma.The dome is mantled by strongly deformed quartz schist and marble.The THS in the study area is dominated by Triassic-Cretaceous sedimentary rocks such as siltstone,sandstone,and some slate.One of the prominent and well-studied NHGDs,called Yala-Xiangbo or Yardoi(Aikman et al.2008;Zeng et al.2011,2015;Hou et al.2012),is situated 40 km north of the Cuonadong gneiss dome(Fig.1b).The Yala-Xiangbo granitoids formed around 44–41 Ma(Zeng et al.2015)and thenearby Dala granitoids around 44 Ma(Aikman et al.2008)by partial melting of amphibolite under crust-thickening conditions(Zeng et al.2015).In the southern section adjacent to the STDS,zircon U–Pb agesindicate the Tsona leucogranite crystallized at 18.8±1.2 Ma(Aikman et al.2012) and the Cuona leucogranite formed at 17.7±0.3 Ma(Wang et al.2016).Such granitic magmas are considered to be extension-driven and caused by decompression melting;upward migration of such melts may initiate extension on a large scale(Aoya et al.2005).

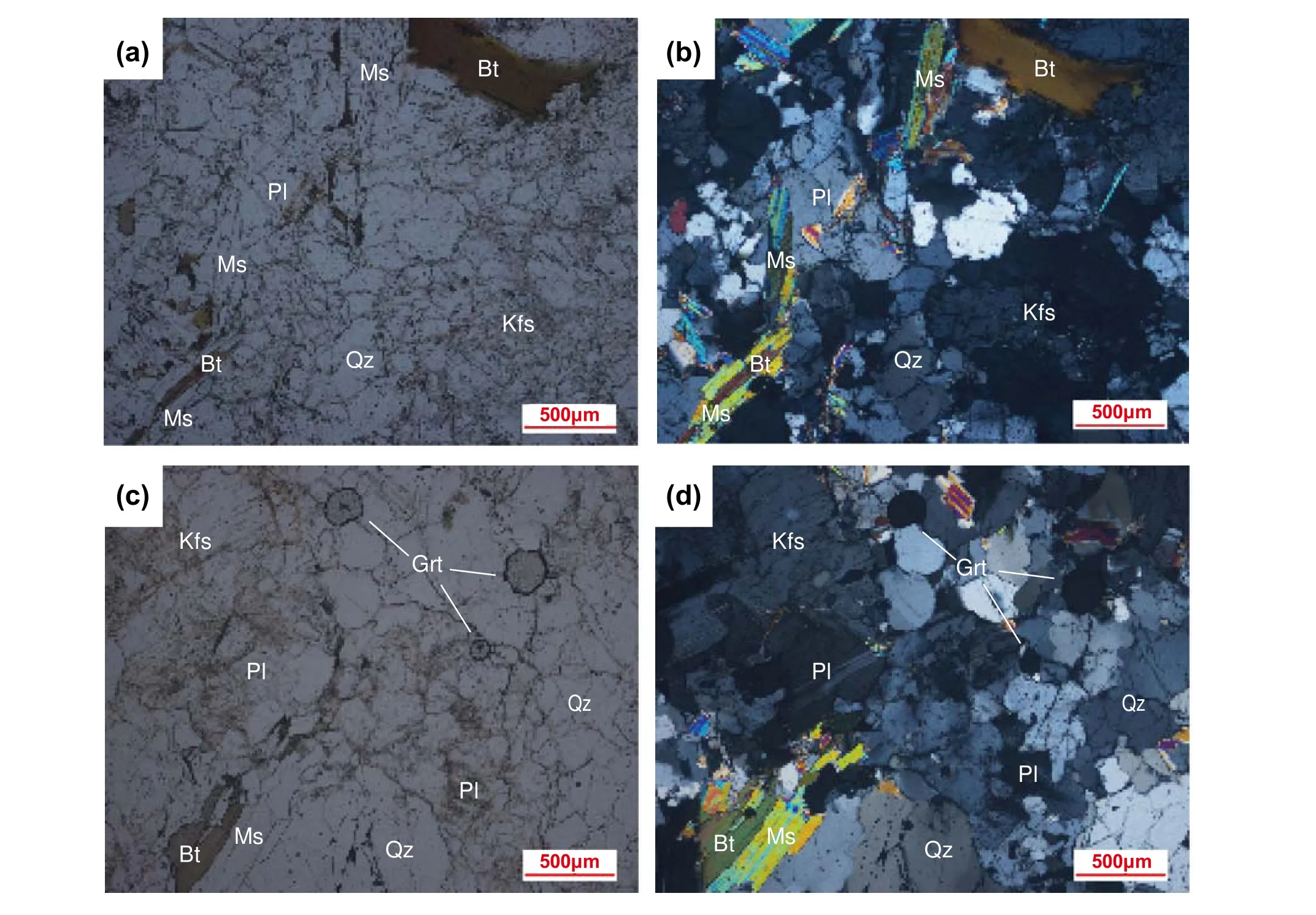

The essentially undeformed leucogranite in this study is exposed in the western Cuonadong gneiss dome(Fig.1b)and has a rather uniform mineralogical composition of quartz,plagioclase,K-feldspar,muscovite,biotite,and garnet grains(<5%)(Fig.2).The light-brown garnet grains show euhedral and crack-free characteristics with grain size of 50–100 μm,suggesting that they are primarily of magmatic origin.Accessory minerals(zircon,apatite,and monazite)are rare.

3 Analysis methods

In this study,several leucogranite samples from the Cuonadong gneiss dome were examined.Sample locations are presented in Fig.1b.SIMSzircon U–Pb dating,major and trace element analyses,and Sr–Nd isotope analyses were carried out at the State Key Laboratory of Isotope Geochemistry,Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry,Chinese Academy of Sciences.The40Ar/39Ar laser stepwise heating experiments were performed on a multicollector ARGUS VI noble gas mass spectrometer at the Key Laboratory of Tectonics and Petroleum Resources(China University of Geosciences,Wuhan),Ministry of Education(Bai et al.2018).

Fig.2 Photomicrographs showing textures and mineral assemblages of Cuonadong leucogranite samples from the Cuonadong gneiss dome,composed of quartz,plagioclase,K-feldspar,muscovite,biotite,and garnet(less than 5%).Bt:biotite;Grt:garnet;Kfs:K-feldspar;Ms:muscovite;Pl:plagioclase;Qz:quartz;Tur:tourmaline.Minerals abbreviations after Whitney and Evans(2010)

3.1 SIMS zircon U–Pb isotope analyses

Zircons were separated using conventional heavy liquid and magnetic separation techniques.Then intact zircon grains were handpicked,mounted in epoxy resin,and polished to equatorial sections.Before analysis,optical and cathodoluminescence(CL)imaging were used to determine the target domains of individual zircon for isotope spot analyses and to avoid the internal structures of zircon such as inclusions,cracks,and other imperfections.CL images were taken with a JEOL JXA-8100 Superprobe set at 10 kV with WD=13.6 mm.Measurements of U,Th,and Pb isotopes were performed on a SIMS Cameca IMS-1280 HR ion microprobe,following the analytical procedures described by Li et al.(2009).The zircon standard Qinghu(159± 0.2 Ma,2σ)was used as a suitable working reference material of U–Pb age for the microbeam analysis of unknown zircon samples.The ellipsoidal spot is about 20× 30μm in size on zircons.Uncertainties on single analysis are reported at the 1σlevel.

3.2 Mica 40Ar/39Ar stepwise heating experiments

Rock samples were crushed to 180–250 μm in a stainlesssteel mortar and single muscovite grains were separated by hand picking under a binocular microscope.Muscovite grains were then cleaned in an ultrasonic bath with deionized water for 15 min.Sample and monitor standard ZBH-2506(biotite with age of 132.7±0.5 Ma)were irradiated in the China Mianyang Research Reactor for 48 h.Samples were step-heated using a continuous wave CO2laser instrument(50 W)and argon isotopes were measured using a multicollector ARGUS VI noble gas mass spectrometer(Bai et al.2018).The40Ar/39Ar dating results were calculated and plotted using the ArArCALC software by Koppers(2002).Correction factors for interfering argon isotopes derived from irradiated CaF2and K2SO4are:(39Ar/37Ar)Ca=6.175×10-4,(36Ar/37Ar)Ca-=2.348×10-3and(40Ar/39Ar)K=2.323×10-3,(38-Ar/39Ar)K=9.419×10-3. Detailed Instrument introduction and analytical procedures are described in(Bai et al.2018).Errors of40Ar/39Ar ages in this study are quoted at 2σ.

3.3 Major and trace element analyses

Whole rock samples,excluding the weathered materials,were crushed into small pieces in a stainless-steel mortar with a stainless-steel pestle,then finely powdered in an agate mortar to<74μm for bulk rock major,trace,and rare earth element(REE)analyses.Major element analysis was performed on X-ray fluorescence(XRF;Rigaku ZSX100e).Analytical uncertainties are mostly between 1 and 5%.Trace elements,including REEs,were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry(ICP-MS;Thermo iCAPQc).Precision and accuracy of trace element analyses were mostly within 5%.

3.4 Sr and Nd isotopic analyses

Sr and Nd isotopic analyses were performed on 150 mg powdered samples and element separation was undertaken by conventional ion-exchange techniques in an ultra-clean chemical laboratory.Sr and Nd isotope compositions were determined by multi-collector ICP-MS(Thermo Scientific Neptune).The87Sr/86Sr ratio of NBS-987 standard and143Nd/144Nd ratio of the Shin Etsu JNDi-1 standard were used to monitor the detector efficiency drift of the instrument and produced ratios of 0.710262± 9(1σ)and 0.512105± 5 (1σ), respectively. All measured143Nd/144Nd and86Sr/88Sr ratios were fractionation corrected to146Nd/144Nd=0.7219 and86Sr/88Sr=0.1194,respectively.The initial Sr and Nd isotopic compositions were calculated at 16 Ma based on the SIMS U–Pb age.

4 Results

4.1 Geochronology

4.1.1 SIMSzircon U–Pb dating

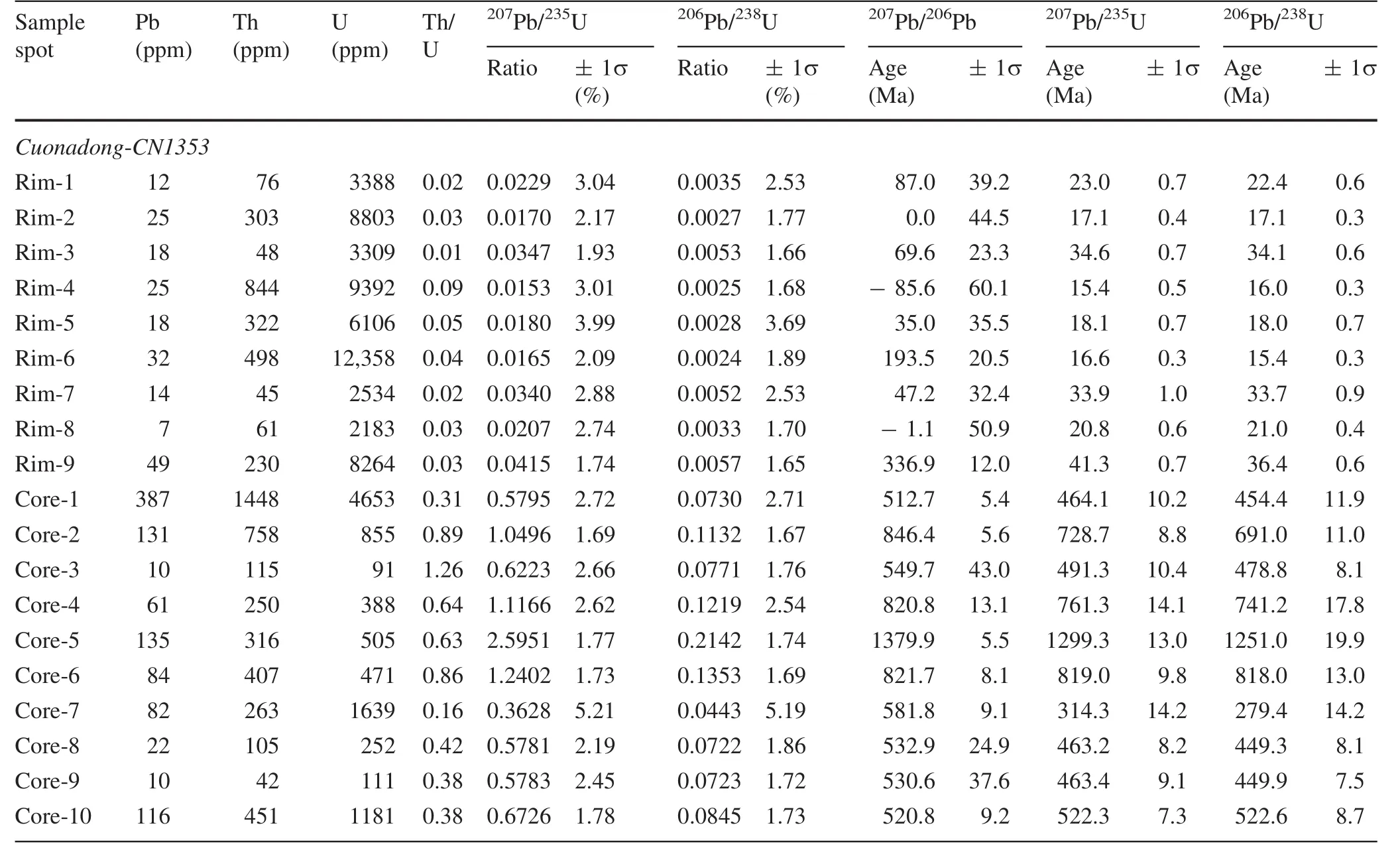

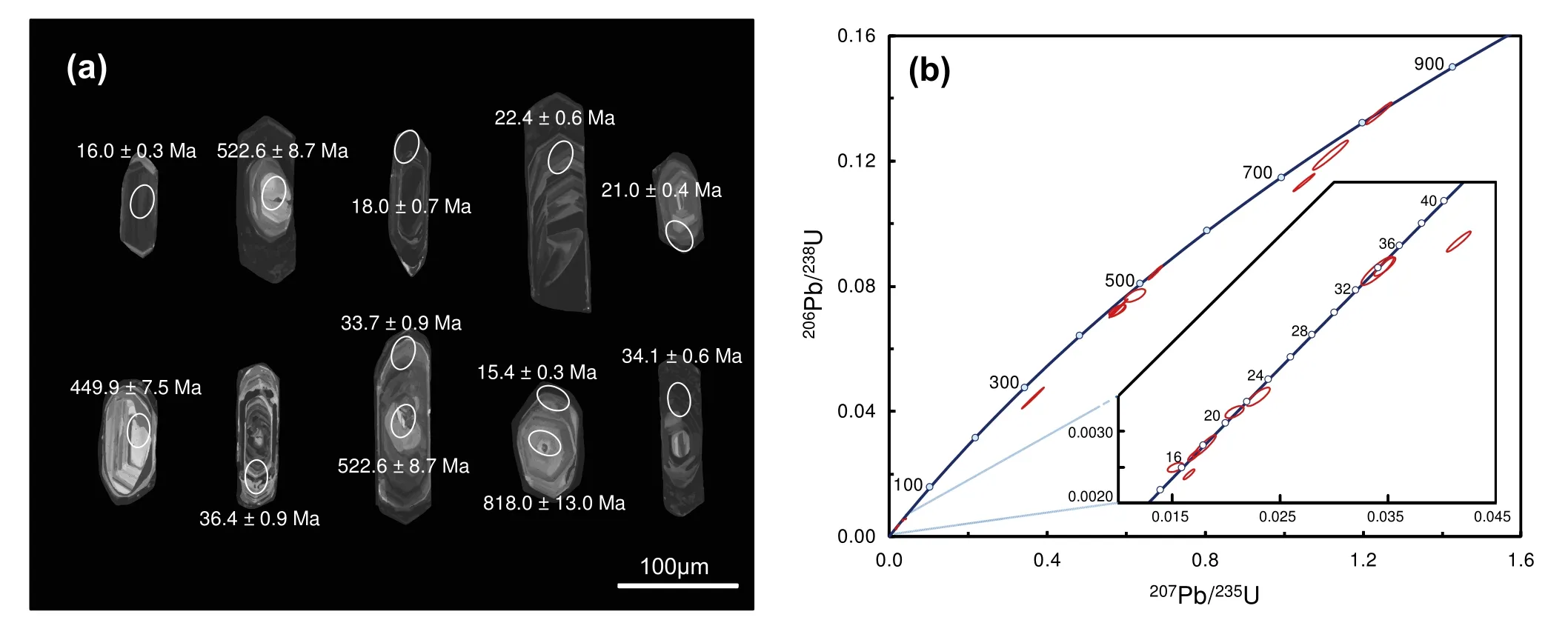

To constrain the emplacement age of the Cuonadong leucogranite,we carried out in situ high-resolution ion microprobe(SIMS)U–Pb spot analyses of zircon.U,Th,and Pb concentrations and isotopic ratios of zircon sample CN1353 are shown in Table 1.

The zircons of sample CN1353 from the Cuonadong leucogranite had euhedral to subhedral morphologies,with an average crystal length of 100μm and length to width ratios of about 2:1–3:1.Almost all zircons displayed corerim textures,with rims showing igneous oscillatory zoning on CL images(Fig.3a).Some zircons were characterized by a sponge-like texture in the rims; these were avoided for analysis.Nine spots were analyzed on the oscillatory zoned rims of zircons to constrain the timing of this magmatic event.These spots yield apparent206Pb/238U ages ranging from 36.4±0.6 to 15.4±0.3 Ma(Fig.3b)with especially low Th/U ratios from 0.01 to 0.09(Table 1).Four spots(Rim-1,-3,-7,and-8)with ages of 34.1 to 21.0 Ma were characterized by relatively lower U contents(2183–3388 ppm),in contrast with other rim spots with ages of 18.0 to 15.4 Ma and much higher U contents(6106–12358 ppm).The exception was Rim-9(36.4 Ma,8264 ppm U),indicating that the rims may have formed in different magmatic stages.U content increased withmagma evolution.In other words,high U content and low Th/U ratios are characteristic of the Cuonadong leucogranite.The oldest and youngest rim points(Rim-9,36.4 Ma and Rim-6,15.4 Ma)clearly deviated from the concordia curve (Fig.3b), showing Pb loss.The concordant ages of rim spots ranged from 34.1 to 16.0 Ma,providing age constraints on initial magma and emplacement of the Cuonadong leucogranite.Ten analyses on zircon cores yielded a wide range of206Pb/238U ages from 1251 to 279 Ma,with an age group of 500 to 450 Ma

(n=5)(Table 1 and Fig.3b).These core spots are characterized by higher Th/U ratios(0.16–1.26)than zircon rims(0.01–0.09).The differences between Th/U ratios in the zircon rims and cores indicate that they formed in different geologic environments.

Table 1 SIMSU–Pb isotope data of zircons from the Cuonadong leucogranite

Fig.3 a Representative cathodoluminescence images of sample CN1353 showing the textures and spots of zircon,and the corresponding 206Pb/238U ages(1σ).b U–Pb concordia diagrams of sample CN1353.Error ellipses are shown for 1σ level of uncertainty

4.1.2 Muscovite 40Ar/39Ar laser stepwise heating

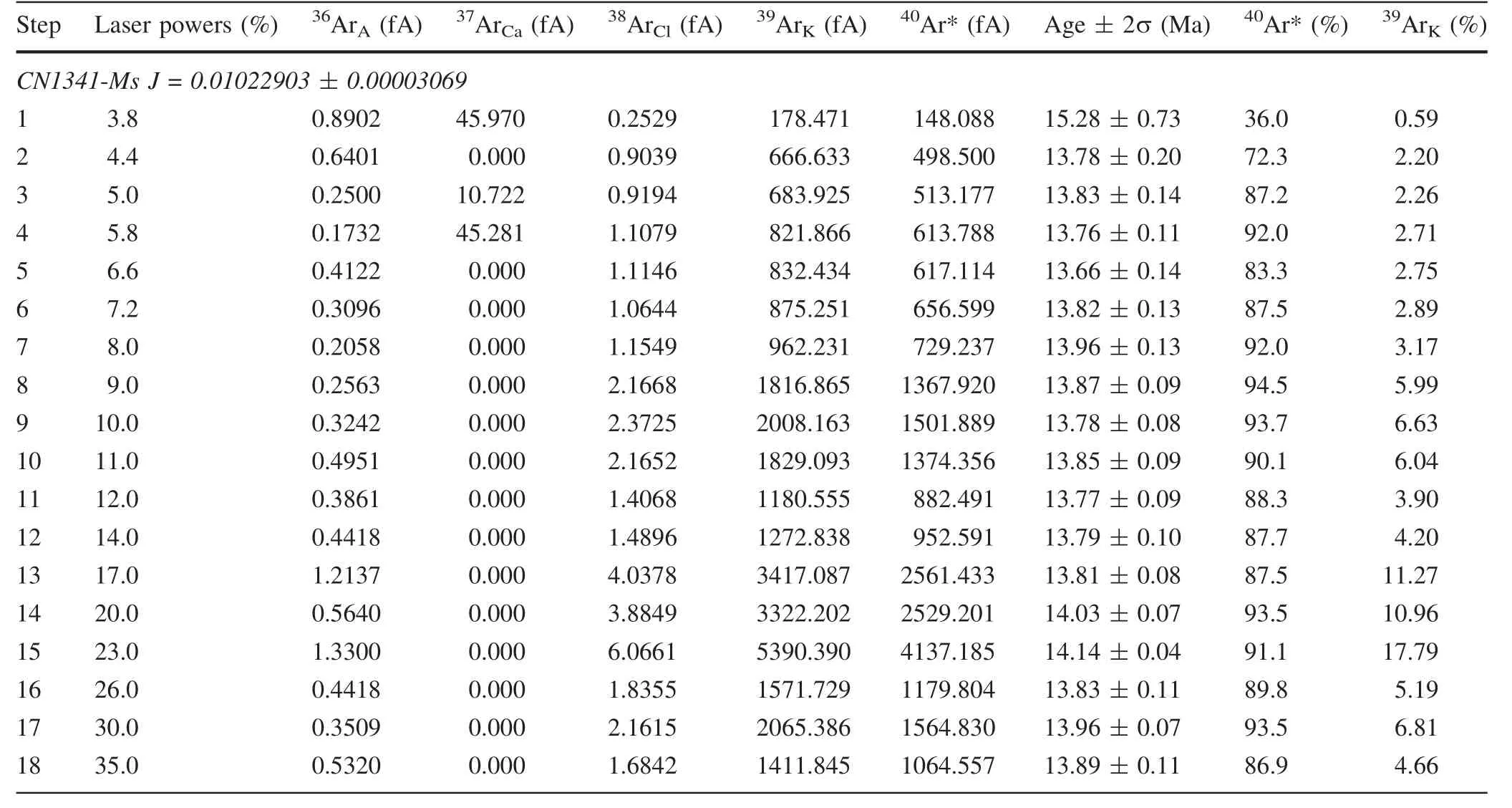

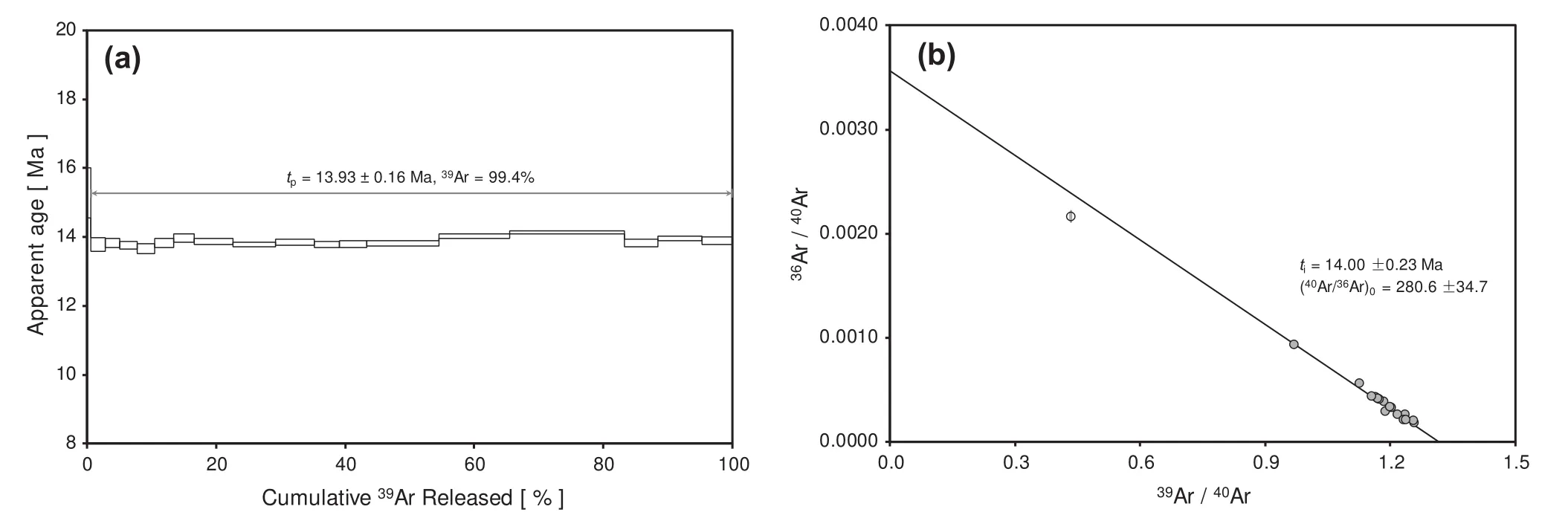

A muscovite sample,CN1341,from the Cuonadong leucogranite was analyzed by40Ar/39Ar laser stepwise heating and the corresponding ages are shown in Table 2 and Fig.4.

The muscovite crystals in Cuonadong leucogranite usually have euhedral shapes with clean crystal terminations,indicating that they are magmatic phase(Barbarin 1996).Muscovite crystals in this study were fresh and did not suffer from hydrothermal alternation(Fig.2).As shown in Fig.4,sample CN1341 yielded a flat40Ar/39Ar age spectrum with a plateau age of 13.93±0.16 Ma(cumulative39ArKreleased=99.41%).The argon isotopic data well-define an isochron corresponding to an age of 14.00±0.23 Ma, with initial40Ar/36Ar ratio of 280.6±34.7.We were unable to separate a biotite sample for40Ar/39Ar dating from the rock due to biotite’s scarcity and inter growth with muscovite(Fig.2).

4.2 Geochemistry characteristics

4.2.1 Major elements

Analysis data of the whole-rock major(wt%)and trace(ppm)elements for the Cuonadong leucogranite are listed in Table 3.Samples had uniform compositions of major elements,characterized by a relatively restricted range of high SiO2(71.01%–74.62%)and high alkali(Na2-O+K2O>8%),belonging to the high-K calc-alkaline series.However,CaO,TiO2,MnO,and Fe2O3T contents were relatively low.Therefore,all samples returned very low MgO/(FeO+MgO)values ranging from 16.69 to 26.31,suggesting they were generated from relatively evolved melts.Aluminum saturation index(ASI)of the samples ranged from 1.20 to 1.26,indicating the leucogranites are strongly peraluminous.

4.2.2 Trace elements and rare earth elements

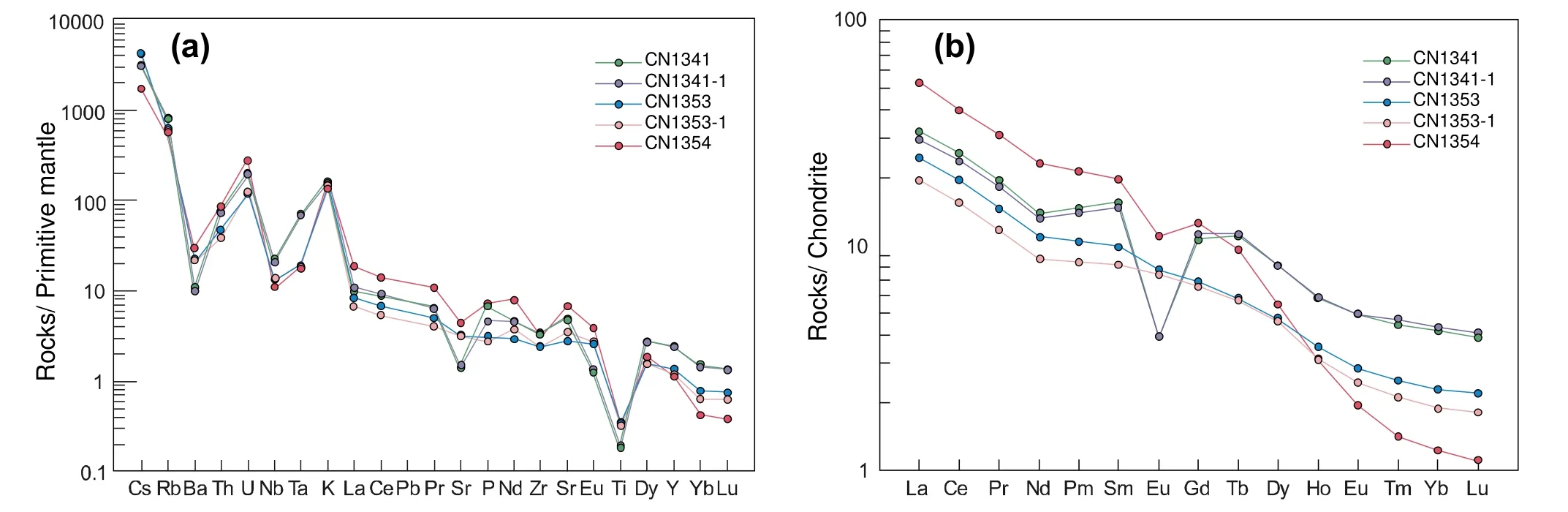

Like for the major elements,the leucogranite samples displayed a consistent pattern of trace elements,with enrichment in large-ion lithophile elements and depletion in high field-strength elements in their primitive mantlenormalized trace element patterns(Fig.5a).Samples were enriched in Cs,Rb,K,Pb,U,and light REEs,but depleted in Nb,Ta,Ti,Zr,Ba,Sr,heavy REEs(HREEs),and Y.Although Ba and Sr are large-ion lithophiles,theirconcentrations were significantly low.Rb/Sr ratios were very high(3–17),and exhibited a trend of increasing Rb/Sr with decreasing Ba(Fig.8).A chondrite-normalized REE diagram(Fig.5b)shows that all leucogranite samples were enriched in light REEs,but depleted in HREEs,with(La/Yb)Nratios ranging from 7.6 to 43.4.Two samples showed weak Eu anomalies or no Eu anomaly while other samples had obvious negative Eu anomalies.Sample CN1354 did not contain any garnet(a mineral with a strong capacity for HREEs),resulting in serious HREE depletion(Fig.5b)in comparison to garnet-bearing samples.Most Himalayan leucogranites show negative Eu anomalies,but some others have been reported to lack Eu anomalies(Gao and Zeng 2009;Wu et al.2015;Zeng and Gao 2017),warranting further investigated.

Table 2 Muscovite 40Ar/39Ar dating results by laser stepwise heating from the Cuonadong leucogranite

Fig.4 Age spectrum(a)and inverse isochron(b)of muscovite sample CN1341 from the Cuonadong leucogranite by 40Ar/39Ar laser stepwise heating

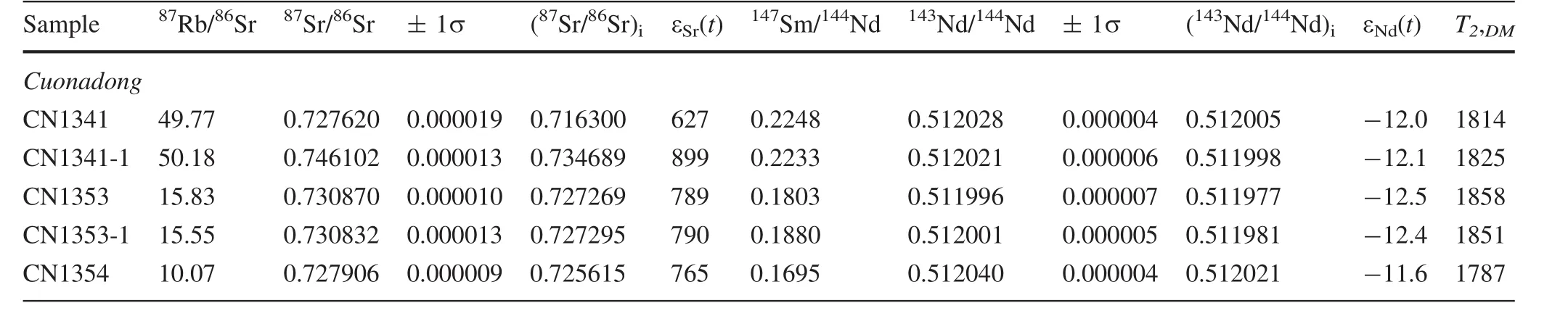

4.2.3 Sr–Nd isotope

Whole-rock Sr and Nd isotopic data for the Cuonadong leucogranite are reported in Table 4.A value t=16 Ma was assigned to calculate initial Sr and Nd isotopic compositions.Initial87Sr/86Sr ratios ranged from 0.71630 to 0.73469,and initial Nd isotopic ratios from 0.51198 to 0.51202,with a range ofεSr(t)from+627 to+899 and εNd(t)from-11.6 to-12.5,strongly indicating that the Cuonadong leucogranite had a crustal source for Tertiary melting(Zhang et al.2004).

5 Discussion

5.1 Emplacement and cooling ages of the Cuonadong leucogranite

Our new SIMS U–Pb dates from the new-growth zircon rims yielded widely scattered206Pb/238U ages spanning several million years from 34.1 to 16.0 Ma(Table 1 and Fig.3).Such a broad distribution of zircon rim U–Pb ages has three possible causes:(1)high-U content in zircon resultsin Pb loss by radiogenic damage(White and Ireland 2012);(2)zircons containing high[U+Th]can yield positive correlations between[U]or[U+Th]and the apparent ages(Aikman et al.2012);(3)the overgrowth rims of zircon grains record a long history of crust-derived granitic melts(Rubatto et al.2013).In this study,most data points of high-U content(2183–12,358 ppm)analysisspots on zircon rims are on the concordia curve(Fig.3b),not showing Pb loss(two spots from Rim-9 and Rim-6 being the exceptions).Due to potential effects on zircon,the accessory mineral monazite,which is free from the high-U effect(Wu et al.2015),is applied to dating the Himalayan leucogranites.However,such scattered ages of Himalayan leucogranites has not only been found in zircon U–Pb dates(Aoya et al.2005;Kellett et al.2009;Aikman et al.2012),but also in monazite U–Th–Pb dates(Aikman et al.2012;Lederer et al.2013;Rubatto et al.2013).Thus,the scattered ages of zircon rims probably reflect a prolonged period of crustal melting.In addition,the U and Th contents varying with the growth of zircon rims indicates slow magma evolution.Previous studies have proposed slow accretion of crustal-derived leucogranite magmas with no mantle supply(Annen et al.2006)and granitic melt production over several million years(Harris et al.2000;Booth et al.2009).Recently,Hopkinson et al.(2017)provided evidence supporting the theory that Himalayan leucogranites formed by pure crustal melts without mantle contributions.

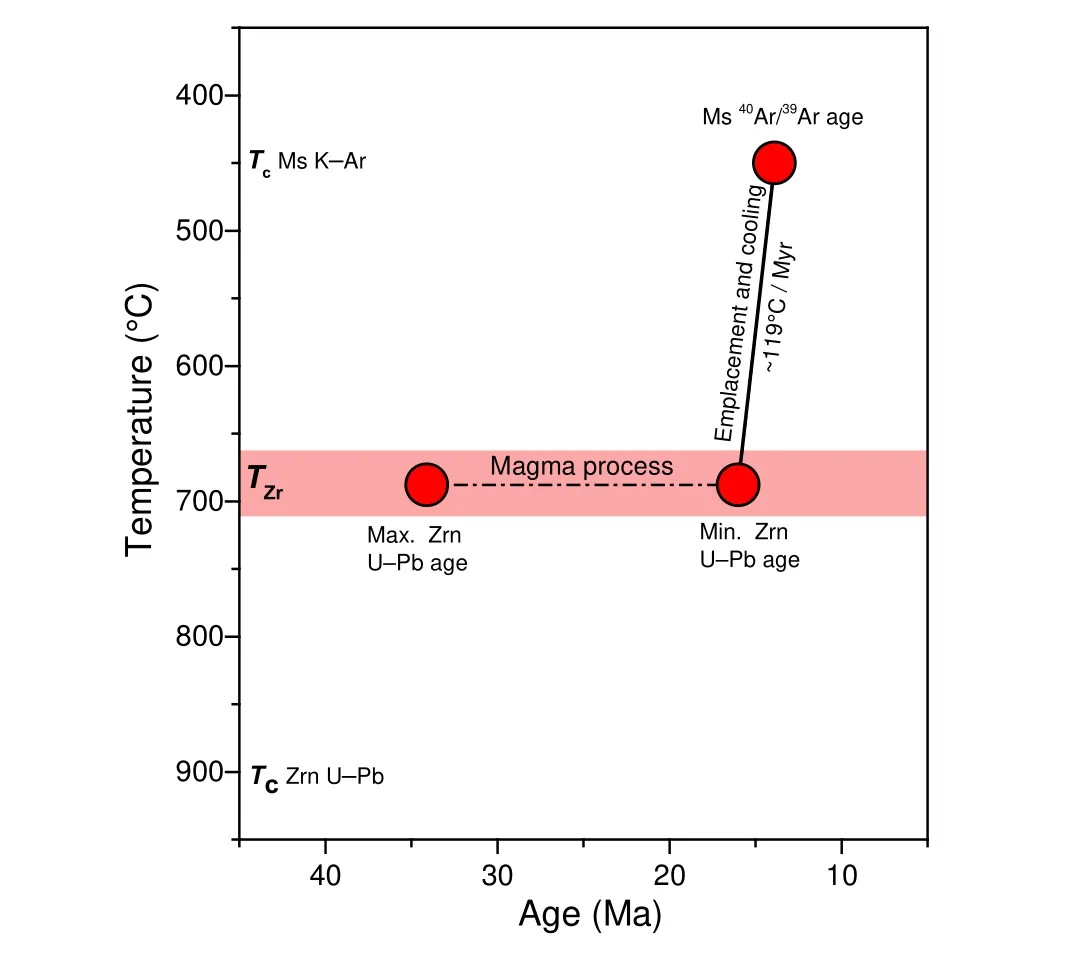

Zircon saturation temperatures(TZr)(Watson and Harrison 1983;Miller et al.2003)can be applied to estimate initial magma temperatures at the source.In this study,TZrof the Cuonadong leucogranite were calculated as 662–711 °C(mean 688 °C)(Table 3).TZrcalculated frombulk rock compositions provide a minimum estimate of temperature if the magma was undersaturated,but a maximum if it was saturated(Miller et al.2003).Since abundant inherited zircon grains have been found in the Cuonadong leucogranite,its maximum initial magma temperature was about 710°C at the source,similar to other North Himalayan leucogranites(Zhang et al.2004;Gao and Zeng 2014)and indicating the temperatures of these magmas were low(~ 700 °C).Because the closure temperature(Tc)of the zircon U–Pb system(about 900 °C)(Cherniak and Watson 2001)is significantly higher than the temperatures of leucogranite magmas,the inherited zircons have been widely preserved in almost all Himalayan leucogranites and thus the zircon rims grew throughout the magmatic process,recording a large spread in U–Pb ages.Based on the youngest concordant U–Pb age of zircon rims,the emplacement of the Cuonadong leucogranite probably occurred at 16 Ma.

Table 3 Whole-rock major and trace element compositions of leucogranites from the Cuonadong gneiss dome

Fig.5 a Primitive mantle normalized multi-element patterns.b Chondrite-normalized rare earth element patterns.Primitive mantle and chondrite normalization values are from Sun and McDonough(1989)

Table 4 Sr and Nd isotope data of the Cuonadong leucogranite

40Ar diffusion in muscovite was revised by Harrison et al.(2009),showing that retention of Ar in muscovite is substantially greater than previously assumed.Recent studies have further constrained muscovite closure temperaturesat:410–470 °C(van Rooyen et al.2016),460 °C(Fournier et al.2017),and 490°C(Schultz et al.2017).In this study,muscovite40Ar/39Ar laser stepwise heating yielded a flat age spectrum(Fig.4a),indicating that the muscovite of the Cuonadong leucogranite has remained a closed K–Ar system and has not been thermally disturbed sincecrystallization(McDougall and Harrison 1999).Thus,the muscovite40Ar/39Ar age indicates the Cuonadong leucogranite cooled below 450°C at 14 Ma.

Rapid cooling of the Cuonadong leucogranite is supported by the minor difference between the U–Pb age of 16 Ma and the muscovite40Ar/39Ar age of 14 Ma.Based on the average zircon saturation temperature of 688°C(Table 3)at 16.0±0.3 Ma and the muscovite Ar closure temperature of 450°C at 13.9± 0.16 Ma,a rapid cooling rate of 119°C/Ma was determined for leucogranite emplacement and cooling(Fig.6).An exhumation rate of 3 km/Maat 16–14 Maisbased on ageothermal gradient of 40°C/km(Nelson et al.1996),and is consistent with the exhumation rate of 3–4 km/Ma during the same period for the Qomolangma detachment of Himalaya(Schultz et al.2017).Therefore,the geochronological dates of the Cuonadong leucogranite imply rapid exhumation of the eastern Himalaya at 16–14 Ma.This is consistent with Aikman et al.(2012),who found that the nearby Dala granitoids experienced rapid exhumation at 15 Ma.

Fig.6 Calculated temperature–time path for the Cuonadong leucogranite.The closure temperature(T c)of the zircon U–Pb system is greater than 900°C(Cherniak and Watson 2001),and that of the muscovite K–Ar system 450 °C(see ‘‘Discussion’’).The calculated zircon saturation temperatures(T Zr)of the leucogranite are from 662 to 711 °C(Table 3),which emplaced at 16 Ma and cooled to 450 °C at 14 Ma with a rapid cooling rate of 119°C/Ma

5.2 The source region

Elementary and isotopic analyses characterized the Cuonadong leucogranite as high SiO2(>71%)and strongly peraluminous(ASI>1.2),with high initial87Sr/86Sr(0.72–0.73)and negative εNd(t)values(-11.6 to-12.5).These characteristics are similar to other Miocene Himalayan leucogranites,indicating that they were derived from the crust(Scharer et al.1986;Lefort et al.1987;Guo and Wilson 2012).Previous studies have demonstrated that NHGs originated from:(1)the GHC(Zhang et al.2004;King et al.2011);(2)a mixture between the Lesser Himalayan Sequence(LHS)and GHC(Murphy 2007;Pullen et al.2011;Guo and Wilson 2012);or(3)metasedimentary units of gneiss domes in the Tethyan Himalaya(Aikman et al.2008;King et al.2011).The THS is another possible source region of the NHG due to the isotopic characteristics and spatial relationship of the THS and NHG.However,experimental studies have shown that anatexis occurred at depths of 15–20 km(Patiño Douce and Harris 1998).Due to the low metamorphic grade of sedimentary rocks of the Tethyan Himalaya,leucogranites cannot have been generated from such a region unless the THSwasburied deeply at crustal levels,ascenario that has not yet been identified(Zhang et al.2004).

Sr and Nd isotopic analyses in bulk rock samples can identify possible source regions of melts.Combined with published Sr and Nd isotope data(all ratios re-corrected to 16 Ma)of the GHC and LHS,the Cuonadong leucogranite is isotopically similar to metasedimentary rocks of the GHC(Fig.7),although the initial Sr isotopic values are slightly lower(0.7163–0.7347).Nevertheless,the LHS is characterized by larger variations in Sr isotopes and lower εNdvalues,precluding it as the source of the Cuonadong leucogranite.In addition,based on the lithotectonic unitsof the eastern Himalaya(Bhutan),Richards et al.(2006)reported significantly distinct Nd model ages of metapelites between the GHC (1700–2200 Ma) and LHS(2500–2600 Ma).In comparison,the Nd model agesof the Cuonadong leucogranite of 1787–1858 Ma(Table 4)are identical to GHC metapelites,further indicating that the Cuonadong leucogranitewasgenerated from the GHC.The distinct isotopic differences of the eastern Himalaya are comparable with the equivalent units from the central Himalaya(Richards et al.2006),indicating that different parts of the Himalayan orogen probably have experienced varied geological histories,and thus have significantly distinct characteristics(Yin 2006;Aikman et al.2012).Therefore,the hypothesis that Himalayan leucogranites in diverse locations derived from different source regions is probably tenable.For example,the leucogranites in the Xiao Gurlaarea and the Gurla Mandhata metamorphic core complex of the western Himalaya are considered to be derived from anatexis of the GHC and LHSrocks(Murphy 2007;Pullen et al.2011).

Highly heterogeneous Sr isotopic compositions are characteristic for almost all Himalayan leucogranites(Deniel et al.1987;Lefort et al.1987;Scaillet et al.1990;Guo and Wilson 2012).The initial87Sr/86Sr ratios of the Cuonadong leucogranite have a relatively wide range(0.7163 to 0.7347),showing largeisotopic variation even at the meter scale,similar to other HHLs(Lefort et al.1987;Scaillet et al.1990)and most NHGs(Guo and Wilson 2012).This characteristic of the Himalayan leucogranites is one of many open questions and many hypotheses are proposed to explain this phenomenon.Previous studies indicate that the initial Sr isotopic variations could come from(1)heterogeneous source and poor mixing of magma batches during magma segregation and transport from its source(Deniel et al.1987;Copeland et al.1990);(2)progressive melting of a single metasedimentary source(Inger and Harris 1993;Knesel and Davidson 2002);(3)fluid interaction during magma evolution(Lefort et al.1987;Prince et al.2001);or(4)contamination of wallrocks during magma ascent and emplacement(Liu et al.2014,2016).Every interpretation above is reasonable under certain circumstances,and most likely morethan one mechanisms influenced the process of leucogranite formation in such complex collisional orogenesis.However,if initial Sr isotopic variations derived from post-magmatic hydrothermal alteration or contamination of wall-rocks,the characteristic of geochemistry and the isotopic compositions of these leucogranites would represent the magma source(Liu et al.2014,2016).

From the perspective of highly viscous melts(Deniel et al.1987;Scaillet et al.1996)and rapid magma emplacement(Lefort 1981;Copeland et al.1990;Lederer et al.2013)of the Himalayan leucogranites,such isotopic heterogeneities most likely derived from their source region.Our geochronological data further suggest that the emplacement of the Cuonadong leucogranite took place rapidly.In addition,considering that the metasedimentary rocks of the GHC also have heterogeneous initial Sr isotope compositions(Deniel et al.1987),even though leucogranites were not generated from progressive melting of a single metasedimentary source(Knesel and Davidson 2002),such heterogeneities from source rocks of the GHC can be preserved in their products.Thus,the heterogeneous Sr isotopic compositions also support the GHC as the source region of the Cuonadong leucogranite.

5.3 Melting mechanism

Previous studies on petrology and geochemistry have demonstrated that the Himalayan leucogranites were generated by partial melting of metasedimentary rocks,driven by fluid-absent mica(muscovite or biotite)breakdown(Harris and Inger 1992;Inger and Harris 1993;Patiño Douce and Harris 1998;Knesel and Davidson 2002).In recent years,two-mica granites in Sakya and Malashan gneiss domes were determined to be generated from fluidfluxed melting of metasediments(King et al.2011;Gao and Zeng 2014).Harrison et al.(1999)suggested that breakdown of muscovite during dehydration melting preferentially releases Rb over Sr,producing the high Rb/Sr ratios observed for the leucogranites.In contrast,fluid fluxed melting produces melts with lower Rb contents but higher Sr contents than melts derived from fluid-absent melting(Harris and Inger 1992;Prince et al.2001).For example,two-mica granites of the Malashan gneiss dome which formed around 17 Maarecharacterized by higher Sr contents (>146 ppm), but lower Rb contents(<228 ppm).According to detailed research by Gao and Zeng(2014),the Malashan two-mica granites derived from fluid-fluxed melting of metasediments.

In addition,as suggested by Inger and Harris(1993),muscovite dehydration breakdown would produce a rich residual K-feldspar,with which Ba is highly compatible.Consequently,this mechanism could result in distinct Ba depletion and negative Eu anomalies.Thehigh Rb/Sr ratios observed for the Cuonadong leucogranite ranged from 3.5 to 17.3(Table 3),much higher than the Malashan twomica granites(Rb/Sr<1.3)(Aoya et al.2005;Gao and Zeng 2014).From Ba–Rb/Sr systematics(Fig.8),the Cuonadong leucogranite shows distinct Ba depletion along with the elevated Rb/Sr ratios.Apparently,Malashan twomica granites have abundant Ba and much lower Rb/Sr ratios, distinguishing them from the Cuonadong leucogranite(Fig.8).Therefore,the characteristics of high Rb/Sr(> 3.5),low Sr/Ba(< 0.5)ratios,and negative Eu anomalies of the Cuonadong leucogranite(Table 3)suggest fluid-absent melting of muscovite from a metapelitic source.This is also supported by the studies of Gao et al.(2017).

Fig.8 Ba–Rb/Sr systematics of the Cuonadong leucogranite based on Inger and Harris(1993).FA:fluid-absent melting;FP:fluidpresent melting.Data of the Malashan granites are from Aoya et al.(2005)and Gao and Zeng(2014)

6 Conclusions

The first comprehensive investigations of the leucogranite exposed in the Cuonadong gneiss dome are presented in this study.The major points are summarized here:

1. The scattered U–Pb ages of zircon rims from 34.1 to 16.0 Ma suggest protracted melting of the mid-crust,or that formation of the crustal-derived magma took a long time.

2. The muscovite40Ar/39Ar laser stepwise heating analyses yielded an essentially flat age spectrum,exhibiting closed K–Ar system behavior of the Ar release pattern.40Ar/39Ar dating revealed that the Cuonadong leucogranite cooled down to 450°C at 14 Ma.

3. The youngest U–Pb age of the zircon rims and the muscovite40Ar/39Ar age suggest that the Cuonadong gneiss dome experienced rapid emplacement and exhumation with a cooling rate of 119°C/Ma during 16–14 Ma.

4. Geochemical characteristics demonstrate that the Cuonadong leucogranite derived from partial melting of metapelite from the GHC under fluid-absent muscovite melting conditions.Rapid cooling of the Cuonadong leucogranite indicates that the eastern Himalaya experienced rapid exhumation around 16–14 Ma.The ductile extension of the STDS in southern Tibet probably ceased by about 14 Ma.

AcknowledgementsWe are grateful to Yuanbao Wu and Defeng He for their constructive suggestions.Weappreciate the assistance of Lin Ma for field sampling,and Xianglin Tu for trace element analyses.We also thank Yingde Jiang and Ming Xiao for their helpful discussion.This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(Nos.41630315,41503053 and 41688103).

Ahmad T,Harris N,Bickle M,Chapman H,Bunbury J,Prince C(2000)Isotopic constraints on the structural relationships between the Lesser Himalayan Series and the High Himalayan Crystalline Series,Garhwal Himalaya.Geol Soc Am Bull 112:467–477

Aikman AB,Harrison TM,Lin D(2008)Evidence for early(>44 Ma)Himalayan crustal thickening,Tethyan Himalaya,southeastern Tibet.Earth Planet Sci Lett 274:14–23

Aikman AB,Harrison TM,Hermann J(2012)Age and thermal history of Eo-and Neohimalayan granitoids,eastern Himalaya.JAsian Earth Sci 51:85–97

Annen C,Scaillet B,Sparks RSJ(2006)Thermal constraints on the emplacement rate of a large intrusive complex:the Manaslu Leucogranite,Nepal Himalaya.JPetrol 47:71–95

Aoya M,Wallis SR,Terada K,Lee J,Kawakami T,Wang Y,Heizler M(2005)North-south extension in the Tibetan crust triggered by granite emplacement.Geology 33:853

Bai XJ,Qiu HN,Liu WG,Mei LF(2018)Automatic40Ar/39Ar dating techniques using multicollector ARGUS VI noble gas mass spectrometer with self-made peripheral apparatus.J Earth Sci 29:408–415

Barbarin B(1996)Genesis of the two main types of peraluminous granitoids.Geology 24:295–298

Booth AL,Chamberlain CP,Kidd WSF,Zeitler PK(2009)Constraints on the metamorphic evolution of the eastern Himalayan syntaxis from geochronologic and petrologic studies of Namche Barwa.Geol Soc Am Bull 121:385–407

Cherniak DJ,Watson EB(2001)Pb diffusion in zircon.Chem Geol 172:5–24

Copeland P,Harrison TM,Lefort P(1990)Ageand cooling history of the Manaslu granite:implications for Himalayan tectonics.JVolcanol Geotherm Res 44:33–50

Deniel C,Vidal P,Fernandez A,Lefort P,Peucat JJ(1987)Isotopic study of the Manaslu granite(Himalaya,Nepal)—inferences on the age and source of Himalayan leukogranites.Contrib Mineral Petrol 96:78–92

Fournier HW,Lee JKW,Urbani F,Grande S(2017)The tectonothermal evolution of the Venezuelan Caribbean Mountain System:40Ar/39Ar age insights from a Rodinian-related rock,the Cordillera de la Costa and Margarita Island.J S Am Earth Sci 80:149–173

Fu J,Li G,Wang G,Huang Y,Zhang L,Dong S,Liang W(2017)First field identification of the Cuonadong dome in southern Tibet:implications for EW extension of the North Himalayan gneiss dome.Int JEarth Sci 106:1581–1596

Gao LE,Zeng LS(2014)Fluxed melting of metapelite and the formation of Miocene high-CaO two-mica granites in the Malashan gneiss dome,southern Tibet.Geochim Cosmochim Acta 130:136–155

Gao LE,Gao JH,Zhao LH,Hou KJ,Tang SH(2017)The Miocene leucogranite in the Nariyongcuo Gneiss Dome,southern Tibet:Products from melting metapelite and fractional crystallization.Acta Petrol Sin 33:2395–2411

Guo ZF,Wilson M(2012)The Himalayan leucogranites:constraints on the nature of their crustal source region and geodynamic setting.Gondwana Res 22:360–376

Harris NBW,Inger S(1992)Trace-element modeling of pelitederived granites.Contrib Mineral Petrol 110:46–56

Harris N,Vance D,Ayres M(2000)From sediment to granite:timescales of anatexis in the upper crust.Chem Geol 162:155–167

Harrison TM,Grove M,Lovera OM,Catlos EJ(1998)A model for the origin of Himalayan anatexis and inverted metamorphism.JGeophys Res[Solid Earth]103:27017–27032

Harrison TM,Grove M,McKeegan KD,Coath CD,Lovera OM,Le fort P(1999)Origin and episodic emplacement of the Manaslu intrusive complex,central Himalaya.JPetrol 40:3–19

Harrison TM,Celerier J,Aikman AB,Hermann J,Heizler MT(2009)Diffusion of40Ar in muscovite.Geochim Cosmochim Acta 73:1039–1051

Hopkinson TN,Harris NBW,Warren CJ,Spencer CJ,Roberts NMW,Horstwood MSA,Parrish RR,EIMF(2017)The identification and significance of pure sediment-derived granites.Earth Planet Sci Lett 467:57–63

Hou ZQ,Zheng YC,Zeng LS,Gao LE,Huang KX,Li W,Li QY,Fu Q,Liang W,Sun QZ(2012)Eocene-Oligocene granitoids in southern Tibet:constraints on crustal anatexis and tectonic evolution of the Himalayan orogen.Earth Planet Sci Lett 349–350:38–52

Inger S,Harris N(1993)Geochemical constraints on leucogranite magmatism in the Langtang Valley,Nepal Himalaya.J Petrol 34:345–368

Kawakami T,Aoya M,Wallis SR,Lee J,Terada K,Wang Y,Heizler M(2007)Contact metamorphism in the Malashan dome,North Himalayan gneissdomes,southern Tibet:an example of shallow extensional tectonics in the Tethys Himalaya.JMetamorph Geol 25:831–853

Kellett DA,Grujic D,Erdmann S(2009)Miocene structural reorganization of the South Tibetan detachment,eastern Himalaya:Implications for continental collision.Lithosphere 1:259–281

King J,Harris N,Argles T,Parrish R,Zhang H(2011)Contribution of crustal anatexis to the tectonic evolution of Indian crust beneath southern Tibet.Geol Soc Am Bull 123:218–239

Knesel KM,Davidson JP(2002)Insights into collisional magmatism from isotopic fingerprints of melting reactions.Science 296:2206–2208

Koppers AAP(2002)ArArCALC-software for40Ar/39Ar age calculations.Comput Geosci 28:605–619

Gao LE,Zeng LS(2009)Early Oligocene Na-rich peraluminous leucogranites in the Yardoi gneiss dome,southern Tibet:formation mechanism and tectonic implications.Acta Petrol Sin 25:2289–2302

Lederer GW,Cottle JM,Jessup MJ,Langille JM,Ahmad T(2013)Timescales of partial melting in the Himalayan middle crust:insight from the Leo Pargil dome,northwest India.Contrib Mineral Petrol 166:1415–1441

Lee J,Whitehouse MJ(2007)Onset of mid-crustal extensional flow in southern Tibet:evidence from U/Pb zircon ages.Geology 35:45

Lefort P(1981)Manaslu leucogranite—a collision signature of the Himalaya a model for its genesis and emplacement.JGeophys Res[Solid Earth]86:545–568

Lefort P,Cuney M,Deniel C,Francelanord C,Sheppard SMF,Upreti BN,Vidal P(1987)Crustal generation of the Himalayan leucogranites.Tectonophysics 134:39–57

Li XH,Liu Y,Li QL,Guo CH,Chamberlain KR(2009)Precise determination of Phanerozoic zircon Pb/Pb age by multicollector SIMS without external standardization.Geochem Geophys Geosyst 10:Q04010

Lin B,Tang J,Zheng W,Leng Q,Lin X,Wang Y,Meng Z,Tang P,Ding S,Xu Y,Yuan M(2016)Geochemical characteristics,age and genesis of Cuonadong leucogranite,Tibet.Acta Petrol Mineral 35:391–406(in Chinese with English abstract)

Liu ZC,Wu FY,Ji WQ,Wang JG,Liu CZ(2014)Petrogenesisof the Ramba leucogranite in the Tethyan Himalaya and constraints on the channel flow model.Lithos 208:118–136

Liu ZC,Wu FY,Ding L,Liu XC,Wang JG,Ji WQ(2016)Highly fractionated Late Eocene(~35 Ma)leucogranite in the Xiaru Dome,Tethyan Himalaya,South Tibet.Lithos 240:337–354

McDougall I,Harrison TM (1999)Geochronology and thermochronology by the40Ar/39Ar method.Oxford University Press,Oxford

Miller CF,McDowell SM,Mapes RW(2003)Hot and cold granites?Implications of zircon saturation temperatures and preservation of inheritance.Geology 31:529–532

Murphy MA(2007)Isotopic characteristics of the Gurla Mandhata metamorphic core complex:Implications for the architecture of the Himalayan orogen.Geology 35:983

Nelson KD,Zhao WJ,Brown LD,Kuo J,Che JK,Liu XW,Klemperer SL,Makovsky Y,Meissner R,Mechie J,Kind R,Wenzel F,Ni J,Nabelek J,Chen LS,Tan HD,Wei WB,Jones AG,Booker J,Unsworth M,Kidd WSF,Hauck M,Alsdorf D,Ross A,Cogan M,Wu CD,Sandvol E,Edwards M(1996)Partially molten middle crust beneath southern Tibet:synthesis of project INDEPTH results.Science 274:1684–1688

Patiño Douce AE,Harris N(1998)Experimental constraints on Himalayan anatexis.JPetrol 39:689–710

Prince C,Harris N,Vance D(2001)Fluid-enhanced melting during prograde metamorphism.JGeol Soc 158:233–241

Pullen A,Kapp P,DeCelles PG,Gehrels GE,Ding L(2011)Cenozoic anatexis and exhumation of Tethyan sequence rocks in the Xiao Gurla Range,Southwest Tibet.Tectonophysics 501:28–40

Richards A,Argles T,Harris N,Parrish R,Ahmad T,Darbyshire F,Draganits E(2005)Himalayan architecture constrained by isotopic tracers from clastic sediments.Earth Planet Sci Lett 236:773–796

Richards A,Parrish R,Harris N,Argles T,Zhang L(2006)Correlation of lithotectonic units across the eastern Himalaya,Bhutan.Geology 34:341–344

Rubatto D,Chakraborty S,Dasgupta S(2013)Timescales of crustal melting in the Higher Himalayan Crystallines(Sikkim,Eastern Himalaya)inferred from traceelement-constrained monazite and zircon chronology.Contrib Mineral Petrol 165:349–372

Scaillet B,Francelanord C,Lefort P(1990)Badrinath-Gangotri plutons(Garhwal,India):petrological and geochemical evidence for fractionation processes in a high Himalayan leucogranite.JVolcanol Geotherm Res 44:163–188

Scaillet B,Holtz F,Pichavant M,Schmidt M(1996)Viscosity of Himalayan leucogranites:Implications for mechanisms of granitic magma ascent.J Geophys Res [Solid Earth]101:27691–27699

Scharer U,Xu RH,Allegre CJ(1986)U–(Th)–Pb systematics and ages of Himalayan Leucogranites,South Tibet.Earth Planet Sci Lett 77:35–48

Schultz MH,Hodges KV,Ehlers TA,van Soest M,Wartho J-A(2017)Thermochronologic constraints on the slip history of the South Tibetan detachment system in the Everest region,southern Tibet.Earth Planet Sci Lett 459:105–117

Sun SS,McDonough WF(1989)Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts:implications for mantle composition and processes.Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 42:313–345

van Rooyen D,Carr SD,Gibson D(2016)40Ar/39Ar thermochronology of the Thor-Odin—Pinnacles area,southeastern British Columbia:tectonic implications of cooling and exhumation patterns.Can JEarth Sci 53:993–1009

Wang XX,Zhang JJ,Yan SY,Liu J(2016)Age and geochemistry of the Cuona leucogranite in southern Tibet and its geological implications.Geol Bull China 35:91–103(in Chinese with English abstract)

Watson EB,Harrison TM(1983)Zircon saturation revisited—temperature and composition effects in a variety of crustal magma types.Earth Planet Sci Lett 64:295–304

White LT,Ireland TR(2012)High-uranium matrix effect in zircon and its implications for SHRIMP U–Pb age determinations.Chem Geol 306:78–91

Whitney DL,Evans BW(2010)Abbreviations for names of rockforming minerals.Am Mineral 95:185–187

Wu FY,Liu ZC,Liu XC,Ji WQ(2015)Himalayan leucogranite:petrogenesis and implications to orogenesis and plateau uplift.Acta Petrol Sin 31:1–36(in Chinese with English abstract)

Yin A(2006)Cenozoic tectonic evolution of the Himalayan orogen as constrained by along-strike variation of structural geometry,exhumation history,and foreland sedimentation.Earth-Sci Rev 76:1–131

Yin A,Harrison TM(2000)Geologic evolution of the Himalayan-Tibetan orogen.Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 28:211–280

Zeng LS,Gao LE (2017)Cenozoic crustal anatexis and the leucogranites in the Himalayan collisional orogenic belt.Acta Petrol Sin 33:1420–1444

Zeng LS,Gao LE,Xie KJ,Liu ZJ(2011)Mid-Eocene high Sr/Y granites in the Northern Himalayan Gneiss Domes:melting thickened lower continental crust.Earth Planet Sci Lett 303:251–266

Zeng LS,Gao LE,Tang SH,Hou KJ,Guo CL,Hu GY(2015)Eocene magmatism in the Tethyan Himalaya,southern Tibet.Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 412:287–316

Zhang HF,Harris N,Parrish R,Kelley S,Zhang L,Rogers N,Argles T,King J(2004)Causes and consequences of protracted melting of the mid-crust exposed in the North Himalayan antiform.Earth Planet Sci Lett 228:195–212

Zhang Z,Zhang LK,Li GM,Liang W,Xia XB,Fu JG,Dong SL,Ma GT(2017)The cuonadong gneiss dome of North Himalaya:a new member of gneiss dome and a new proposition for the orecontrolling role of north Himalaya gneiss domes.Acta Geosci Sin 38:754–766(in Chinese with English abstract)

杂志排行

Acta Geochimica的其它文章

- Geochemistry and geochronology of Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous intrusions related to some Au(Sb)deposits in southern Anhui:a case study and review

- Re–Os dating of molybdenite and in-situ Pb isotopes of sulfides from the Lamo Zn–Cu deposit in the Dachang tin-polymetallic ore field,Guangxi,China

- Major Miocene geological events in southern Tibet and eastern Asia induced by the subduction of the Ninetyeast Ridge

- Using electrogeochemical approach to explore buried gold deposits in an alpine meadow-covered area

- U–Pb zircon age of the base of the Ediacaran System at the southern margin of the Qinling Orogen

- Organic carbon content and carbon isotope variations across the Permo-Triassic boundary in the Gartnerkofel-1 borehole,Carnic Alps,Austria