A NEW CONCEPT AND EXHIBITION PROGRAM FOR THE EGYPTIAN MUSEUM IN CAIRO

2018-06-22MohamedGamalRashed

Mohamed Gamal Rashed

Damietta University

1. Introduction

In parallel to the ongoing plans and anticipated opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) and the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC),1Rashed 2015a, 165–174; 2015b, 84–86.the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (EMC) will need to revise its display concept (Fig. 1).Eventually, it will become necessary to redraw its mission and objectives to ensure the continuity of its effective role towards its visitors and communities, and to meet the expectations of 21st century audiences. The recent decade has witnessed numerous challenges facing EMC, either because of its insecure status during and after the 2011 revolution;2Rashed 2016a; 2016b, 125–130.or because of the distribution of its collections among other museums.3Ibid.

This paper aims to propose a plan for its future permanent display. Meanwhile,it is necessary to deliberate and evaluate its future exhibition plans in relation to its targeted audiences,4Black 2005, 46–73. It is necessary to launch a research project on the current visitors and the local communities in order to understand their needs, interests, and expectations. This is an essential part of the strategic planning process, which must be achieved first in order to engage the expected audiences. For the recent research in engaging audiences, their types, interests and expectations, cf.Black 2005; Paris 2002; Falk and Dierking 1992; Falk, Dierking and Foutz 2007.collections, exhibition spaces, advantageous location in the capital, the recent changes in Egyptian society, and the parallel major museum projects in Cairo.5Rashed 2015c.Thus, it is necessary to consider using the most updated methods of display and interpretation, understanding the current exhibition spaces, and utilizing different modes of flexible display in different galleries.The aim is to meet the different expectations of the traditional audience,6Rashed 2017, 1–11.while attracting to new types of visitors.7Falk discusses how museums can work better for their visitors, through museum exhibits and programs, allowing them to achieve multiple, personally relevant goals. Falk 2009, 215–216.The suggested “general concept of display”would focus on the themes of “ancient Egyptian art” and “archaeological fieldwork in Egypt,” which will be illustrated by applying different modes of display, such as aesthetic, thematic, contextual and/or systematic.8Maximea 2014, 99 and 105–108.

As will be discussed later, three core ideas are recommended to be presented addressing different types of visitors. The first idea, a museum for “Ancient Egyptian Art,” which is already one of those previously suggested.9See: http://www.kairo.diplo.de/contentblob/3926336/Daten/3348650/ku_aegyptisches_museum_01.pdf (30.12.2016).It has been modified, in the current proposal, in the form of an exhibition program with a thematic structure to be adopted only in the round galleries of the ground floor,instead of the whole museum (plan I). The second idea, an “Archaeological Fieldwork Museum,” illustrating the history of Egyptian archaeology, where objects can be exhibited in connection to their archaeological contexts from discovery to display (plan I). The third idea is a “Visible Storage Display” (plan II). Guidelines are introduced for the project management, a strategic plan,working teams, and the budget for implementation.10The pedagogical research will be discussed in a forthcoming study in the development of the interpretation plan, as an essential portion of its development which must be based on pedagogical research preceding the project.

1.1. The Current Permanent Display

EMC is one of the most famous museums in the world for its unique collection of Egyptian antiquities. It was built in a neo-classical design by the French architect Marcel Dourgnon. Its cornerstone was laid on April 1, 1897, and it officially opened on November 15, 1902, housing a few thousand Egyptian antiquities.The museum now boasts 107 halls, and over 160,000 objects, on display and in storage, covering the time span from Prehistory to the Roman period (Figs. 2–11).The display is distributed between two floors in addition to the open air display in the Museum’s garden. The ground floor display follows a chronological order from the predynastic to the Roman period, with a few exceptions where extra heavy artifacts are located around the ground floor galleries (Figs. 2–7).On the first floor, visitors can get different experiences exploring the complete collections of related objects, tombs (e.g. “Tutankhamun,” “Yuya and Tyua”), or even categories and typological collections such as papyri, ostraca, coffins, etc.(Figs. 8–11). The second floor and the basement are used as storerooms housing tens of thousands of objects.11Liesgang 2014; Hawas 2005; Rashed 2015a, 165–174.

Since 2011, EMC has faced huge challenges and difficulties. Its location in the heart of Tahrir Square placed the museum in the center of the threats during the revolution.12The challenges have been discussed widely on several occasions, cf. Rashed 2015a, 165–174;2016a, 55–59; UNESCO Culture 2012; El Dorry 2011.Among the several challenges that EMC is now facing is the redistribution of its current collections among EMC, GEM, and NMEC. A number of selection committees were appointed to distribute the collection to the other museums, but the concepts of display in the three museums were not clearly formulated, creating duplications in the selection and repetition of highlighted themes and topics, thus disconnecting the unity of some of the collections.13Rashed 2014a.The proposed concept and exhibition program aim to provide the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities with some suitable plans for EMC.

EMC should develop its mission and objectives and, based on those, set a strategic plan for this transitional stage. The museum needs to establish its social role with respect to the local communities, as it should be a platform for social inclusion,14Salving and Fleming 2013, 134–171. Museums are first and foremost social environments, for social dynamic groups. Taking in account that visitors often come to the museum as a part of a social group, museums have to consider the social context for, and of, these groups. Cf. Falk and Dierking 1992, 41–54. On the other hand, museums are excellent platforms for social inclusion of very diverse communities among the museum audience. For instance, the cities which populations consist of people with different culture, language, and traditions; their museums can play a proactive role as a platform for social inclusion of these communities through presenting the culture of these groups within exhibitions and other events or programs, while making sure to involve these communities in the making of such activities. It means that each community can introduce their culture to the others, e.g., what LACMA museum in Los Angeles do for the several communities of the immigrated communities. Cairo is a major city which host millions of inhabitants from different nationalities,including more than five millions from Syria, Libya, Iraq, Palestine, and Yemen among other foreigner communities. Thus, EMC should play a proactive role towards these different communities in Cairo.not solely a touristic destination frequented exclusively by foreigners.15Rashed 2015a, 165–174; 2015c.The inclusive audience contributions to museums have come to be understood as “co-creation.”16Cf. Simon 2010, 263–280. Simon stated the main reasons that cultural institutions engage in co-creative projects, and which EMC should consider in order to succeed in engaging the local communities in particular and to book a higher place among the other competitive museums and cultural institutions in Cairo. The main reasons according to the study of Simon are: to give voice and be responsive to the needs and interests of the local community members; to provide a place for the community engagement and dialogue; to help participants develop skills that will support their own individual and community goals. Cf. Simon 2010, 263.Therefore, the proposed concept, storylines,and pedagogical programs17Cf. Falk, Dierking and Adams 2011, 323–339; Black 2005, 121–156, 239–257; Paris 2002; Falk and Dierking 1992; Falk, Dierking and Foutz 2007. Indications will be made only for the pedagogy program when it is necessary, however, the museum must develop a pedagogy research with the communities and the relevant institutions in order to respond efficiently to their expectations and to improve the educational role of the museum in society. It is understood that the educational plan is an essential component of the development of exhibition curatorial brief and program, which must start as early as the development phase. Therefore, it is necessary to start a “user survey” as a part of the educational plan to develop the museum educational role and create equal access to culture for all citizens. The museum should focus on developing new ways of sharing knowledge; and on creating new framework conditions for the development and communication of knowledge that is relevant. It is recommended to follow the steps of previous similar international museum projects.Compare for instance the educational program of the Danish museums, which stated these action areas: 1) development of the educational role of museums, 2) research into education, 3) international experience exchange, 4) museums and education, 5) user surveys, 6) experience exchange and knowledge sharing. Jensen 2013, 28–32.consider the expected types of visitors, which will sustain its role in the 21st century. Throughout the brainstorming phase, different ideas have been discussed.18It is necessary to incorporate co-creative programs together with the diverse communities of the museum, and to avoid any pre-conceived ideas about the outcome of the project by the staff members.Cf. Simon 2010, 268–271. Therefore the proposed concepts here are quite flexible for the input of participants and any expected modifications. Another round of workshops and discussions with the museum staff and representatives of the visitors is a necessity.A list of questions has been circulated and discussed including:

– How can the museum plan and activate its soft power?

– How can the future of the museum be seen through its intended cultural, social and educational roles?

– How can we achieve balance among the three major museums of Cairo?

– How can each of them have its distinct concept?

– What is the most appropriate concept to be developed at EMC?

– Should it be an archaeological resources museum or an ancient Egyptian art museum?

– Should there be a systematic display?

In order to select a concept, the range of visitors and the diversity in the collection must be studied and considered. Who are the expected target audiences?Accordingly, it is understood that if the majority are tourists, tourism companies would definitely prefer GEM for its close location to the Pyramids of Giza. Thus what should EMC offer to convince tourists to keep coming? Whom else can EMC engage?19Black 2005, 46–51 and 61–62.Possibilities are artists, archaeologists, historians, materials specialists,students, and Egyptian families. To keep visitors coming, the display should be designed to attract not only tourists, but also new groups, particularly Egyptians(families, students, and scholars).20Rashed 2017, 1–11; Hooper-Greenhill 2011, 363–375.As for the collection, it is a critical decision to determine which collections must remain at EMC, and which of them may be transferred to other museums. What are the strengths of such collections? What are the stories that can be told? According to the suggested themes (“A Museum for Scholars,” “Ancient Egyptian Art,” “Archaeological Field Museum,” etc.), the two main concepts (a museum for “Ancient Egyptian Art” and “Archaeological Field Museum”) can be illustrated through ancient Egyptian art masterpieces,and representative collections from selected archaeological sites. The repeated objects can be displayed in the form of a “systematic display” according to the classifications of their types, shape, and materials. The balance between these types of permanent display will not just communicate and address the interests of the diverse target audiences, but also put an end to the conflict and the duplication in selection between GEM and NMEC.

1.2. The Methodology

A methodological analysis has been undertaken to select and develop the suitable exhibition program.21Methodologically, the research included descriptive material extracted from semi-structured interviews, panel discussions and mini workshops. For a selection of literature in context, theoretical points of reference were used in addition to elaborated analysis for assessing their applicability.The following points briefly define the applied method and the steps taken:

– Identifying the strengths in the collection.

– Defining the target audiences, their interests and expectations.22Rashed 2017, 3–9; Hooper-Greenhill 2011, 363–375.

– Understanding the current exhibition spaces, their accessibility and flexibility for future rotations and modifications.23Maximea 2014, 99–108; Hillier and Tazortzi 2011, 282–301.

– Studying and suggesting new ideas for the future concept of the display.

– Selecting and testing the most appropriate concept.

– Having discussions to finalize and approve the suggested concept.

– Developing the curatorial brief and the interpretative plan, as a part of the development phase.

– Building the storyline, the layout, and the circulation routes.

– Submitting of the exhibition project to the top management for approval.

– Preparing the objects’ lists, and launching the thematic and object related research.

– Exhibition design process: from schematic design, layout, lighting design and visitors’ circulation to A-Built design.

– Implementing the exhibition up to the opening day.

2. The Proposed Concepts

The concepts for GEM and NMEC have been considered here to avoid any sort of duplication or conflict.24NMEC will be a national museum where the identity of Egypt can be negotiated through the artworks from the long history of Egypt, and aims to present different aspects of the Egyptian civilizations. It will focus on highlighted themes that reflect the social life side rather than its artistic masterpieces. On the other hand, GEM will illustrate “the Broad Story of ancient Egypt,” and “the Kingship;” while mainly addressing the tourists, who often come in groups. Hawas 2005; Rashed 2015a, 165–174; 2015b, 84–86.

2.1. A Museum for “Ancient Egyptian Art”

This has been considered as a concept for the future permanent display of EMC. The considerations that should be taken into account are the number of masterpieces in relation to the exhibition space, and the ongoing selection of a significant percentage of masterpieces to be exhibited in GEM and NMEC.Together, they may mean that the possibility for creating a fully aesthetic display will be uncertain. Thus, dedicating a section of the museum, rather than the whole museum, to present an aesthetic display, would be more appropriate and suitable, and would benefit more diverse types of visitors. On the one hand, it will distinguish EMC, while addressing visitors with interest in art and art history,since neither GEM nor NMEC focus on art. On the other hand, it will help EMC avoid facing the difficulties of the art museums to increase the number of visitors and to address new types of visitors. Presenting art as the sole theme carries the risk of transforming the museum into an art museum, which could mean that EMC might fail both, to perform its social role25Rashed 2017, 1–11.and to compete with GEM and NMEC. Instead, the theme of Egyptian art could be presented according to the types of visitors, types of objects, and the modes by which artifacts can be displayed to communicate to the visitors.

Object types: a selection of “outstanding artifacts” that illustrates a distinguished Pharaonic schools of art, important historical events, periods or persons,etc. to be appreciated for themselves. A significant number of selected objects is expected to be presented in an “aesthetic mode of display”26Molineux 2014, 126–127.to furnish the dedicated galleries according to the motto “less is more.” The dedicated exhibition spaces, the round galleries on the ground floor, provide convenient locations to present the aesthetic display creating the fast tour including the atrium which will house “the council of the pharaohs,” (see below, and plan I).It lays out a simple circulation route for visitors, creating a positive experience.According to the aesthetic mode, the individual objects are presented as outstanding objects. They are to be seen and appreciated for themselves, where the emphasis is placed on the object itself, not on the supporting material. Art galleries and museums typically exhibit their collections in such an aesthetic display. Other modes of display such as contextual, chronological, or thematic arrangement can be used around individual objects in order to enrich the exhibition and to meet the expectations of the visitors.

“Contemplation”27Lord 2014, 15–16.is the appropriate mode of visitors, stimulated by the display of individual ancient Egyptian artifacts that are appreciated in and for themselves.This mode is most familiar at art museums aiming for an aesthetic experience, but it can be applied to archaeology and history museums in displaying masterpieces.Egyptian artifacts present the ancient Egyptian schools of art which have their distinctive styles and perspectives.28It will offer an excellent opportunity for improving the skills of children and school students. The museum educators can offer guide books and programs to the schools teachers and art educators, to help them in teaching.The transformative experience can be found in the enhanced appreciation of the meaning and qualities of each individual work in and for itself. Some objects can be comprehended in relation to the highlighted stories and themes, allowing visitors to discover deeper meanings of the objects. Egyptian artifacts often have significant meanings relating to their functions, purpose, and archaeological contexts; therefore, it is often possible to use them as storyteller, even if they are exhibited in an aesthetic display. All types of visitors can thus have a satisfactory museum experience. Interpretive materials should be provided in a way that meets the different needs of different visitors.29Black 2005, 9–11, 22–36.The galleries of Egyptian art are planned to accommodate both short and long visits. Those who would like to explore a variety of objects and other types of exhibits can find them in other sections of the museum. Accordingly, the art section becomes easily accessible for all types of visitors, while encouraging new types of visitors to be engaged in art.

2.1.1. The Council of the Pharaohs

The atrium “Grande Galerie Centrale” is the largest gallery which lies at the center of the museum, and is accessed directly from the main entrance. Its current display has about one hundred objects, including super heavy artifacts such as the colossi of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye, Ramses II, and the fragment from the floor of the palace of Akhenaton. Other artifacts were added through time causing a crowded display that departs from its original concept (Figs. 2a–b).

The newly suggested concept will simulate the royal palace where the crowned king is on his throne. The architectural design and space of the gallery together with the palace floor and the colossi of the kings will create a significant impact.However, it is alternatively recommended to create what is called the pharaohs’council, where the royal colossi on the high bases represent an imagined council of the kings of ancient Egypt. King Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye are the chairpersons of the council. The floor of the gallery will be designed in the form of a replica of the floor of Akhenaton’s palace, while its pillars, columns, and walls will replicate the decorations of the ancient Egyptian palaces. The two side corridors of the atrium will be able to facilitate a special experience for the gallery while serving as reading areas for the visitors. There will be twelve colossi, which is a significant number that will create a better atmosphere, while allowing the use of the space to house special events receptions, and culturama,etc. in order to enrich the visitors’ experience (compare the Dendur temple gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York). It is suggested also to adapt gallery “P 43” on the first floor with its unique panoramic view overlooking the atrium to set up a “Pharaohs’ Café.” The visitors are invited to enjoy their breaks savuoring a coffee in the presence of the pharaohs, in “Join the Pharaohs’council” (plan II).

2.2. A Museum for Scholars

EMC can be dedicated to house the archaeological collections for the purpose of study and research. There are tens of thousands of objects which have never been shown. GEM is going to be the main destination for tourists, thus, EMC,which may lose most of its masterpieces, can be transformed into a museum for scholars, providing access to its rich collections of Egyptian antiquities. One can compare this, for instance, with the Petrie Museum in London,30See: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums/petrie (01.12.2016).and the ceramic galleries at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (Figs. 12, 13, 15, 16).31See: https://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/ceramics (01.12.2016).The recently opened visible storage galleries at the Egyptian Museum in Turin are also good examples. Such systematic displays are recommended for scholarly study.

Presenting “systematic objects” in a “systematic display” aims to show examples of every type of object and stage of development. Systematic objects refer to the classification of the objects according to the material, type, size,footprint, etc. As for the suitable mode of display, the so-called visible storage“systematic display,”32Molineux 2014, 129–130.is the most effective way to maximize the number of objects on display. In visible storage, museums follow the motto “show, don’t tell.” According to this mode, individual objects are ranged along shelves or in glazed drawers, identified only by a number code that refers visitors to a screen on which to read the entire catalogue entry (Fig. 12);33Ibid., 129.compare the systematic display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 14).34See: http://www.metmuseum.org (01.12.2016).The systematic display allows the museum to show thousands of objects, which can be exhibited according to type, categories, materials, techniques, shape or volume, etc. Often,museums can exhibit 80% of their objects in 20% of their exhibition spaces when they apply this mode of display; while 20% of the objects occupy the 80%percentage of the space in a thematic, contextual or aesthetic display.

Suitable exhibition space to house a systematic display is suggested in most of the upper floor galleries (the eastern wing P15; P20; P25; P30; P35: P40;P45; and the western wing P12; P22; P32: P42; and the southern wing P46–P50)(see plan II), probably in addition to the second floor rooms. The museum’s old fashion showcases can be reused as suitable furniture for display. In addition,some spaces can be dedicated and readapted as classrooms and study spaces serving scholars (e.g. P6–P10 as a study space, and galleries P19; P29; P39 as classrooms (plan II)). The systematic display does not necessarily require building any oriented circulation routes, as visitors can simply walk through the galleries following their interests.

The most preferred mode for visitors to explore a systematic display is“discoveries,”35Lord 2014, 16.and probably “comprehension.”36Ibid.The visitors can explore a range of objects appreciating individual examples or noting relationships among them. This mode is traditionally found in many natural history museums with systematic specimen collections, but now increasingly seen in all types of museums that have adopted the visible storage means of display (e.g. the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Egyptian Museum in Turin).

EMC can satisfy all types of visitors, but mainly the focus will be on scholars and students. Systematic galleries work both for casual browsers and for serious students, who can spend hours or days studying the collections in detail.Moreover, EMC can provide unusual ways of achieving school curriculum targets for the primary, secondary, and private schools in Egypt. School students can learn with objects, sites, and relevant activities at the museum. Systematic display would enhance the curriculum and provoke alternative ways of learning through stimulating senses, arousing curiosity, and unleashing creativity.37Clarke 2002, 5–7.Visible storage will also facilitates educators’ use of the galleries, as students can be assigned to select an object of interest or a relevant subject in order to write a report about it (Fig. 15).38Molineux 2014, 129.Creating a scholarly environment will provide a study and teaching resource for the Departments of Egyptian Archaeology and relevant studies at the Egyptian and international universities;39Hannan, Chatterjee and Duhs 2013, 159–168.compare the case of the Petrie Museum40See: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums/petrie (01.12.2016).in London, where the students often have their practical classes inside the gallery studying the objects.

The “discovery” mode is a visually and intellectually active means of visitor engagement with museum exhibitions. This mode is increasingly seen in all types of museums that have adapted visible storage techniques of display. Discovery of the objects’ meaning may be further enhanced by the provision of full catalogue entries on screens adjacent to the showcases or the gallery. Thus, visitors can discover meanings by themselves, not predetermined by the museum (e.g. the ceramic galleries at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (Figs. 16, 17)).41Crill and Stanley 2010.

It is necessary to integrate the museum-pedagogical research at an early stage of the development phase in order to ensure that it meets the actual needs of the different types of audiences. EMC includes a wide range of audience types and learning styles, so certain target audiences can be selected earlier in order to identify visitor needs.42Rashed 2017, 1–11; Falk, Dierking and Adams 2011, 323–339; Hooper-Greenhill 2011, 363–375.Accordingly, the pedagogical research should define the types of audiences and their needs, as well as the suitable learning styles to be applied, which might include:

– analytical learners

– common-sense learners

– experiential learners

– imaginative learners.43Yousuf 2010, 125–138.

2.3. Archaeological Field Museum44 Though there is an obvious difference between this type and the scholarly museum (2.2); but as it is suggested hereafter, adapting these different types together will help EMC meet the expectations of the different types of visitors.

Studying the archaeological context of the museum objects has been highlighted as a new approach in the field of Egyptology in recent decades.45Schloz 2000. It was also the theme of CIPEG 2014, “Archaeological Sources and Resources in the Context of Museums,” the 31st CIPEG Annual Meeting, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen: http://www.egyptologyforum.org/CIPEG/CIPEG_2014_program.pdf (01.12.2016).Museums started to focus on the context of the objects in their collections, using the objects as the storytellers which may tell unlimited stories through multiple lives. EMC has become a witness in the archaeological field in Egypt during the last two centuries and thus can expand its role and the use of its collections by applying this approach. Creating archaeological field displays will allow EMC to add numerous stories illustrating the lives of each object and collection. The focus on archaeological contexts would make a connection to each archaeological site as well as to each object, set, and Egyptian collection in every museum in the world. Thus, EMC will be able to attain a position as a hub for Egyptology, while creating distinguished displays in GEM and NMEC.

According to this concept, the museum would illustrate the long history of archaeological fieldwork in Egypt through the last two centuries, or even longer.The rich archaeological resources and the records of the excavation expeditions would enrich the display with a broad record of stories around the history and multiple lives of the objects.46Molineux 2014, 127–128.

Other methods of acquiring objects in the past such as purchasing, donations,seizures, and repatriation can also enrich the display. The history of EMC has many of these thrilling stories to be told throughout its galleries, enriching the knowledge of the visitors, while also creating an emotional attachment to the museum and its collections. This is a comprehensive idea for the general concept of the display, or, to be applied in a section of the museum (see plan I, II).

根据昌宁县畜牧养殖业的现状以及目前存在的问题,需要采取有效的解决措施,促进昌宁县畜牧业的健康稳定发展。

In a “contextual display,”46Molineux 2014, 127–128.objects can be allocated in the display according to several contexts: their origin, the discovery, restoration, history of purchasing and acquisition, and even the funny or interesting stories in the lifecycle of the objects. Connections will be made between objects in situ, the distributions,conservation, research and the history of exhibiting the museum objects, as well as the lifestyle in ancient Egypt (i.e. clothes, equipment), etc. The objects are the storytellers that reveal hidden stories to the visitor. The emphasis is on making connections with the visitors and building stories around the objects. The contextual mode is common in history and archaeology museums, though it can be applied to other types of museums.47Ibid., 127.

The second applied mode is the “process display,”48Ibid., 127–128.where the objects are used to communicate how things work or were made; or why something occurs.49Ibid., 128.One example is to show the process of digging in a site, and how objects are unearthed,or to show the reconstruction of a building or of an object. It can be also used to show the conservation steps on some objects. The emphasis here is placed on revealing a sequence of actions or behaviors to lead to a certain outcome. The process display is more familiar to science and technology museums, but it can be used in a wide range of museums (e.g. the Design Museum50See: http://dnstdm.de/en (01.01.2017). It presents the development of designs in a chronological display showing the sequential models of engine, autos, and furniture, etc.in Munich).Adapting process display will be thrilling with antiquities, showing the ancient techniques used by people who lived and died thousands of years ago. In order to adapt contextual and process display, the preferred types of objects are the“outstanding” and “representative objects,” together with their object records and archival materials. It becomes more thrilling for the visitors to discover and dig into the hidden stories behind building the collections. The archival materials can be used either as a part of the display or as a part of the interpretations to tell multiple stories and lives of the objects, and perhaps to highlight the history of the museum itself as well as the excavators and the archaeologists, etc.

Accordingly, the number of objects to be shown is variable, and is open to unlimited number. Each theme, story or sub-theme can be presented using a few objects or hundreds or thousands. The decision is dependent on the available collection, space, and curatorial discretion. It also gives the opportunity to rotate or add new objects to the display. Furthermore, it allows creating a flexible permanent display of “changeable galleries”51Ibid., 121–132.with expected minor or major changes. It is recommended that adaptable exhibition space be in the fourteen interior galleries of the ground floor. Each gallery can be an independent exhibition focusing on an archaeological site, excavation expedition, or even more than one (see plan I, II). The galleries are not built on each other, thus,no oriented route is to be recommended. Visitors can select any of the fourteen galleries according to their interests, where they are encouraged to continue on to discover new galleries.

The recommended modes for visitors’ appreciation are “discoveries,”“comprehension,”52Lord 2014, 16.and “participation.”53Ibid., 18; Simon 2010.The visitors can explore some of these galleries to learn about the stories behind the objects, the work in the field of excavations, and the methods and tools of digging. The galleries would serve also as practical study areas for students and archaeologists, etc. Visitors are also invited to participate and interact with the presented topics and stories throughout the exhibition. They can measure their knowledge about the most famous discoveries and discoverers through question and answer situations. They are invited also to co-create and participate in curating and creating sub-stories and sub-themes that they might find interesting through their experience in the gallery. Their own ideas can adapt and re-use the institutional content to create new meanings and new forms. They will be invited to participate in implementing these ideas at the dedicated changeable exhibition spaces.54Participatory techniques have the particular ability to help visitors develop specific skills related to creativity, collaboration, and innovation. The skills are necessary for people to be successful,productive citizens in a globally interconnected, multicultural world. By other means, activating the museum’s social role in the development of the Egyptian society. Cf. Simon 2010, 193.These displays will satisfy all visitor types. Those best served will be the scholars, students,specialists, newly assigned curators, museum professionals, and archaeologists,who have dedicated interest in more details about certain collections.

The display can be connected to the school curricula of primary, secondary,and high schools. The physical experience of visiting the museum creates special excitement for both students and their teachers, providing unusual ways of learning and fresh ways of thinking while working outside the classroom.Through the galleries and with the assistance of the interpretative materials,we can improve the potential skills of the students. New and meaningful ways of education and meeting targets will be available such as providing access for students to hold the original objects, and to talk with curators and experts inside the gallery. In parallel, it helps the museum engage new generations in building the future museum’s advocates and core visitors.55Clarke 2002, 5–17.It also addresses the tourists who might have special interests or those who decided to spend more time exploring the museum collection. And finally, the local visitors who have the interest to discover and know more about the archaeological sites in their neighborhoods.

3. A Development Plan for the “Archaeological Field Museum”

It is noted that the idea of the Archaeological Field Museum is highly recommended to be implemented together with the themes of “Ancient Egyptian Art,” and “Visible Storage” (for the distribution of the three themes, see plan I, II). It is worthwhile to present additional details for this concept as part of the development phase.56For comparable permanent display projects, however in smaller scales, cf. Salway 2010, 76–101;Wilk 2004.A smaller of permanent exhibition development was designed and implemented at EMC in 2014 (plan III).57A refurbishment of four rooms of the Tutankhamun permanent gallery which aimed to communicate a new mission for EMC with its audience, communities and stakeholders, and to achieve an affordable and practical exhibition project. It had the goal to update partly the non-thrilling display and to showcasing the numerous strength in the unique collection. Thus, the museum intended to a) present its content in the 21st century methods of display, while recalling and preserving its original architectural design, and presenting its unique collections in a distinguished way; b) educate and excite its visitors, both Egyptians and tourists about the story behind the objects, and how to see the objects from different views or prospective, and discovering new meanings; c) create a dialogue between the visitors and the collection through the many spotted questions that visitors may discover themselves. See Rashed 2014b.In addition to the implemented concept(s), certain spaces will be dedicated to additional facilities such as the temporary exhibition space (P11; P16; P21), and multipurpose facilities (P26; P31; P41), etc. (see plan I, II).

3.1. The Type of Collection

– All the archival materials, photographs, drawings, and records of the objects,their excavations, and their life-journeys.

– All the archival materials related to the excavations, including correspondences,agreements, pictures or negatives, equipment of excavations or storerooms, and documentation.58The archival materials are excellent to enrich the display and to interpret the objects or to build stories around them. The exhibitions which include archival materials are considered as either promotional, where the archive is the subject; or educational using the materials for interpretation,which is most recommended here. Casterline, 1980, 11; Allyn, Aubitz and Stern 1987, 402–404.EMC and the Ministry of Antiquities hold tens of thousands of archival materials related to the history of excavations in Egypt and of the history of EMC and its collections. In addition, EMC can obtain copies of the archival materials of foreign institutions with legal agreements as part of a cooperation.

– The acquisition records and documents related to the history of the museum.

3.2. Who Are the Targeted Audiences?

It is necessary to define the museum audiences in order to engage the diverse types of visitors.59Falk 2009, 158–159, 206–207.With whom should the suggested exhibition program communicate, engage, and interact? Does it meet their needs, interests, and expectations?

The secret to attracting and building audiences is helping potential visitors understand that the museum can meet and satisfy their individual identity-related needs.60Ibid., 158.

EMC faces competition with the other cultural, historical, and touristic attractions in greater Cairo. The competition is expected to increase with the anticipated opening of GEM and NMEC which share the same audiences and goals. EMC must develop a strategic plan that includes audience development,61In order to develop a strategic plan including an “audience development,” EMC needs to put the needs of its audiences first, with the understanding of the different kinds of barriers which might exclude people from museums. A full strategic plan should be developed before the implementation phase, while precisely monitored during the implementation. Since audience development is about breaking down the barriers which hinder access to museums, and building bridges with different groups to ensure that their needs have been met. It is a process by which a museum seeks to create access to and encourage greater use of its collections and services by an identified group of people.Audience development is not an optional activity but a way of working which needs to become central to the philosophy and function of the institution. Dodd and Sandell 1998, 6–7.taking into consideration such competitions.62Rashed 2015a, 165–174; 2016a, 55–59; 2016b, 125–130.A distinguished display must be created that meets the expectations of the audiences. This concept will enable EMC to increase its visitor numbers while attracting new types of visitors.63Piacente 2014, 253–263; Lord 2014, 10–14.Accordingly,the target audiences of EMC can be identified as:

– Local communities: addressing all the local communities, families, children,adults, senior citizens, and those who have limited or good standard education.64The author has discussed the needs and the expectations of the Egyptians in a recent article entitled“The Museums of Egypt Speak for Whom?” The article relied on a study, which has been carried in 2016/2017, defines the needs and expectations of the Egyptian communities, and how the Egyptian archaeological museums can meet these expectations. Cf. Rashed 2017, 1–11.They vary between groups that have an interest in museums, others who have no interest, or have not been introduced to museums. It is very important that these groups engage with EMC, but each group has different needs or interests to be met. The education department of EMC must consider different local groups in the early stages of the interpretation planning of the exhibition project. The goal for local communities should be to illustrate “Egyptian identity.”65Falk 2009, 189–191.It is necessary to implement “lifelong learning”66Museums are learning institutions which provide different learning facilities to their audiences.In his study, Harrison distinguished between the lifelong and life-wide learning: “Learning as a preparation for life has been displaced by learning as an essential strategy for successful negotiation for the life course, as the conditions in which we live and work are subject to ever more rapid change… In contemporary conditions, learning becomes not only ‘lifelong’, suggesting learning as relevant throughout the life course, but also ‘life-wide’, suggesting learning as an essential aspect of our whole life experience, not just that which we think of as ‘education’.” In: Clarke 2002, 1; cf. Black 2005,125; also Kaplan 1994; Fladmark 2000; MacDonald and Fyfe 1996.programs to make the museum a “center of learning” for Egyptians. It is noted that learning is not a simple output of teaching since the learning processes involves cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions as well as different levels of engagement and critique.67Illeris 2006, 16.Learners at museums should be provided with access to many different paths to knowledge. In order to be a center of learning, the idea is that EMC would not be limited to providing an exciting display, but it should link the display to the life experiences of different groups of visitors.

– Tourists: providing facilities for leisure time, cultural curiosity, etc. Tourists,who have special interest in archaeology, discoveries, and discoverers, etc.,will find their way to EMC. The museum is surrounded by hotels and tourist destinations in downtown Cairo.

– Primary and secondary school students: providing educational values for developing skills of the students in art, history, sciences as well as the skills of discovery, creativity, and other comprehensive skills. It is supposed that the education department of EMC should develop education programs linked to the schools’ curricula, which apply practical methods of education. It is planned also to prepare special programs for school teachers as a means to prepare them to use the museum galleries for teaching.

– Newly assigned curators, museum staff, and inspectors: the materials and information found throughout the galleries present intensive training for the newly assigned staff. It is important for the career of the junior rank of civil servant in the Ministry of Antiquities to be introduced to the history of his/her archaeological site (among other sites), the excavation methods, techniques,expeditions, their history and achievements, and artefacts discovered at the site.

– Local and international scholars and undergraduate students in the field of Egyptian archaeology and museums: the display will present excellent facilities for building intensive and practical experience. They will be taught about the sites, cultural materials, Egyptian archaeology, and the techniques of digging,This will be in addition to learning about different stones and other materials.The museum studies students can have access to the best practical facilities to learn about exhibitions, museum education, exhibition designs, multimedia and technology as well as interpretation and text writing. Different galleries will apply different techniques while presenting different stories and themes which would create an excellent museum experience. They will be trained through the participation of curating and creating the changeable exhibitions, the regular refurbishments of the permanent displays and the development of temporary exhibitions, etc. As a step towards international collaboration, the students of the relevant institutions around the world are invited to participate during the courses and training programs at EMC. An exchange program is suggested which allows them to study and be trained at EMC, and in return, the professionals of these international institutional counterparts will be invited to deliver lectures, courses and training programs in their respective areas of specialization at EMC.

3.3. Developing the Exhibition Program

The core idea has been briefly articulated in section (2.4), on which the curatorial brief and the interpretation plan can be developed. Thus, the main themes will be only introduced hereafter. The dedicated galleries under this exhibition concept will be divided into five main themes; each of them might have sub-divided stories and themes. Each theme could occupy one or several galleries.

3.3.1. The Introduction Gallery

The introduction gallery includes several sections. The main court will contain a few iconic artifacts to give the first impression about the museum and its collections (room R43, (plan I)). Two other galleries are included and accessed directly from the main court introducing the story of EMC and Egypt landscape.

3.3.1.1. Broad Story of EMC

One gallery would be dedicated to the history of the museum itself. There are thousands of stories that can be told illustrating its long history. The archives of the museum and the records of its collections are rich with numerous interesting stories, in addition to the multi-destination journeys of the museum itself from Azbakia (1835), Boulaq Museum (1858), Giza Museum (1890), to its current location.

3.3.1.2. Egypt Landscape and Topography: Past and Present

A gallery which introduces the landscape and topography of Egypt. Both sections(3.3.1.1 and 2) can be in one room, which is suggested to be room R44 (the access to the room will be transferred to R43, see plan I).

3.3.2. The Archaeological Sites

Rooms R42, R37, R32, R27, R22, R17 and R12 will be dedicated to some archaeological sites (plan I). The archaeological sites will be selected according to the following criteria:

– Different archaeological sites which should vary from small to big sites;presenting various topographical features and representing both upper and lower Egypt (e.g. Abydos, Abusir, Tell el-Faran, Tanis, Bahria Oasis, Sinai, etc.).

– The availability of good quality representative objects at EMC or the storerooms of these sites.

– Representing different historical periods from Prehistory to Ptolemaic Egypt(e.g. Saqqara, Sais, Meidum, etc.).

– Illustrating the characteristic features of ancient and contemporary Egypt(Asuan, Fayum, Siwa oasis, Dahshur, etc.).

– Surviving archaeological sites, which visitors can explore later to discover and learn more (e.g. Saqqara, Tell el-Amarna, Abydos, etc.). One of the lost sites may have a significant value by enriching the experience and imagination of the visitors when using modern technology such as augmented reality (e.g.Heliopolis).

3.3.3. The Archaeological Expeditions in the Field “Behind the Scene”

Rooms R14, R19, R24, R29, and R39 would be dedicated to the achievements of selective expeditions (plan I). The selection depends on building cooperative partnerships to develop exhibition projects, and carry out the thematic research and objects research of exhibition projects. Each gallery is a joint project together with one expedition or more.68EMC have experienced such cooperative projects in the last ten years through series of temporary exhibitions showing the achievements of the foreign expeditions during two centuries.In accordance with the general concept of display, the museum will define the topic of each of the galleries, according to sites, collections, and partner expeditions. These institutions will be invited to participate and cooperate in the development of galleries.

In each gallery, the objects exhibited will be telling several stories and creating thematic, contextual, and/or geographical displays. The achievements of the expedition(s), their technique in digging, research, and activities, will be presented in a storytelling manner. One specific component is to tell the stories behind the scenes about personal experience or accidents of the expedition team or individuals during the digging seasons. Personal stories of famous archaeologists can be told in these displays. These stories could be more interesting for certain types of visitors, who might have less interest in Egyptian art.

3.3.4. The Outdoor Display

The landscape of the open air display plays an essential role in impressing the visitors and engaging the surrounding communities. The museum garden recently gained additional space with a panoramic view of the Nile. It creates the opportunity for different facilities including exhibiting modern artworks, which might be inspired by ancient Egyptian art. This large landscape will be enriched with a selection of ancient Egyptian plants and flora. These, with the view of the Nile, will create good memories for visitors who will be able to experience the integration of the ancient Egyptian landscape as a part of the tour. Additionally,it creates a great facility to run regular social and entertaining activities for the Egyptian communities who may have less interest in visiting museums. The green area and the presented activities can work as a means to engage local communities with the museum over time.

4. The Project Management Strategy

The approved concept and exhibition program should reflect on the mission of the museum and its objectives thereby creating a distinctive identity and concept for EMC. Conflict with GEM and NMEC in both their exhibition concepts and collections must be avoided. The suggested exhibition program “archaeological field museum” is preferred since it would support EMC’s future strategic plan to retrieve its place as a hub for Egyptology while gaining a new role in elevating the field of museum studies. It can become an international center for scientific research and cooperation in Egyptology on both institutional and scholarly levels and act as an institute of museum studies which will integrate theoretical and practical studies as explained below.

4.1. A Platform for International Collaboration

The implementation of the “archaeological fieldwork” would make EMC a platform for Egyptological international collaboration among relevant institutions69All museums with Egyptian collections as well as research and academic institutions focusing on ancient Egyptian archaeology around the world.thereby increasing their benefits. This platform and its expected benefits can be outlined as:

– Entering into several collaborative projects at the same time and gaining the benefits of accessing the most important Egyptian collections worldwide.Museums, institutions, and expeditions which have potential projects to examine and study their own excavations and collections are invited to collaborate. Even scholars and researchers, with their own research projects, are considered to be included into cooperation projects.

– Launching an international project to lead the future research disciplines in Egyptology. Recent projects such as “Re-contextualizing museum objects in their archaeological contexts,” can re-examine the distributed archaeological objects among museums worldwide. The museum’s objective to clean up its archaeological database, and to relate the objects to their essential information and publications will also benefit from this.

– Building strong connections among museums and institutions with Egyptian collections around the world while recalling the “Global Egyptian Museum”project. Accordingly, it is recommended that EMC provides online access to its collection to both scholars and the public, taking the lead to invite institutions that acquire Egyptian antiquities to participate in the initiative of the “Global Egyptian Museum.”

– Maximizing the benefits of cooperation for institutions as well as individual scholars.

– Appreciating the efforts of the excavators, archaeologists, and expeditions over the last two centuries while motivating them to continue their efforts in the field.

4.2. A Flexible Strategic Plan for Implementation70 A full strategic plan is in preparation by the author and will be submitted to the Ministry of Egyptian Antiquities for implementation. A final version of the strategy will be published in a forthcoming article.

Strategic planning can be time-consuming.71Genoways and Ireland 2003, 77; McKenna-Cress and Kamien 2013; Bogle 2013; Sandell and Janes 2007; Lord and Lord 2009, 55–57.Managers should understand that it is not something to be finalized in a few weeks, and that they cannot simply request a strategic plan and expect that it will be ready for implementation in a few months. If the management underestimates the required amount of time and effort, the strategic planning process may simply fail.72Mohamed 2016, 101.Furthermore, the plan should be given the required time for preparation. Creativity will not be achieved unless the whole process is given the time needed. Through the strategic process,the museum staff would be trained to think and act strategically which would permit the museum to handle transformations creatively.73Wright et al. 2007, 2; LaMarre 2014, 379–392.

SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis would be a useful tool to capitalize strengths, minimize weaknesses, exploit opportunities as they arise, and avoid any threats as far as possible.74Vrontis and Thrassou 2006, 136.The challenge is that the museums in Egypt have not been put through a strategic planning process. It is recommended that a strategic plan for the museum be established first, and then a flexible strategic plan for the museum exhibition project be created later, which must be adhered to. The planning process should incorporate the views of all the parties who would be affected by the plan or have a role in its implementation.75Mittenthal 2002, 3.The planning team should identify the parties responsible for completing the tasks related to the strategic objectives and provide a timetable for completion.76Lord and Lord 2009, 55–57. In the second edition, Mrs. and Mr. Lord gave us an excellent example for strategic corporate planning at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, which should be considered by the management of the EMC in their strategic planning for the museum and for the proposed project.Once the strategic framework is ready, then all staff should be taken through it.77Shapiro 2001, 7.The plan should be monitored, controlled, and reviewed in order to ensure that short-term strategies are working towards achieving the long-term objectives and mission of the museum.78Guiltinan and Paul 1988 (cited in McLean 2003, 201).

The entire exhibition project, as well as each subdivided or individual gallery project, must be developed and managed under the supervision of one core management team. The team will also follow the review and evaluation of the implementation of the plan. The evaluation’s intent is not only to evaluate the final results and outcomes, their relevance, cost effectiveness, and sustainability,but also to analyze why certain results have been achieved but not others, and to derive lessons for possible policy review and for preparing the next planning cycle.79Carron 2010, 17.This must be followed by each entity of the project, either the subdivided project by galleries or the plans for the audiences’ engagement, education programs, marketing, etc. The core implementation team will manage the whole project leading the small teams and working groups of each gallery project as well as identifying the tasks and responsibilities of the sub-teams and working groups and the manner of communicating with each other. The schedules are to be settled and managed by the core team. As discussed above, the concept,curatorial brief, and the interpretative plan are the responsibility of the core team and the museum. They must be settled and articulated before forming these working groups and galleries’ teams. The team of each gallery is responsible for the research, development of the interpretative plan, and cooperation with the designers of the galleries for the final implementation of the gallery.

Dividing the exhibition project into small entities allows the museum to manage and achieve the smaller projects. It gives more flexibility in managing and opening some of the galleries, while the work is ongoing in some other galleries. The core team will manage the project as a whole and its subdivided projects to ensure they are integrated with the whole exhibition program and meeting the mission of the museum.

4.3. Teams and Curatorship

Museums are platforms for communication and exchange, not only for visitors but also for professional staff. To achieve a positive result, EMC needs a large team covering the different needed disciplines. EMC will launch its project announcing a call for international collaboration, sponsorship, and fundraising,stating the general plan of the project, primary schedules, rules of collaborations,goals, and returned benefits. Every collaboration should be carefully designed to meet the respective requirements, thus the museum can fulfill its goals covering the gaps that form barriers towards implementation. It is essential to assign a core team for the overall management of the project to manage the working groups and teams of each of the subdivided projects.80EMC has currently a number of well trained professionals covering different disciplines, in addition the Ministry of Antiquities has different experts and specialists covering additional required disciplines. The core team as well as the galleries’ teams will be formed from them. Exceptions will be made to cover the shortage in certain areas such as marketing, fundraising, designing who will be contracted accordingly to the ongoing phases of projects, otherwise to be exchanged with the collaborating institutions. Meanwhile, in the last few years, several training programs have been carried out to train and prepare the museum staff in Egypt with focus on the different areas of museum works.The core team has the responsibility to communicate among all the working groups of each subdivided project and to ensure they are doing their tasks and are meeting the overall objectives. The core team is also responsible for assigning teams and working groups of each of the subdivided projects, according to these guidelines:

– Each subdivided “gallery project” should have an assigned team, consisting of Egyptian and international specialists. International specialists are the representatives of the collaborating institution(s). The representatives of the partners can carry out their tasks at their home institutions. To motivate international institutions to participate in the projects, incentives can be offered such as showing their achievements in the permanent display, and getting more facilities to carry out their research at EMC. Exchanging related information with EMC would be added benefit.

– Each institution can participate in developing one or several galleries, or several institutions can join in one project.

– Creating competition among several teams within different projects will ensure the quality of the display. Each team will do its best to present the best display.The team members from EMC will gain the competitive skills and experience through working with the international partners.

– Collaboration will be proportionate to as many gallery projects there are, which will help the museum retrieve its place as a hub for Egyptology.

5. Conclusion

The permanent display of the Egyptian Museum is an important project for Egypt, thus, its planning stage must consider the Egyptian people as the principal stakeholders and primary audience. It is necessary to set up a strategic plan for the museum, while dividing the whole exhibition project into several smaller projects, which the museum can easily manage and achieve in a timely manner.

The different views of the concept of the future permanent display have been discussed, and the arguments which support the author’s suggestions have been presented. It is recommended to set up an exhibition program combining several concepts and applying several modes of display in order to meet the expectations of the diverse audience. Among the four concepts which are introduced above,three ideas work well together: “Archaeological Field Museum,” “Visible Storage,” together with the theme of “Ancient Egyptian Art.” This relies on the understanding of the current exhibition space at EMC, its rich collections, and the targeted audiences.

EMC has excellent spaces for exhibitions which include more than one hundred halls, with a flexible design that allows several routes for circulation and special exhibitions, together with other related facilities. Thus, dividing the exhibition space into several divisions to present several concepts is a possible solution which also supports the objectives of the museum to address diverse types of visitors. The three suggested ideas will create a thrilling display which meets the diverse targeted audiences, as discussed above, while presenting the collection in different modes of display. The “Archaeological Field Museum,”in particular, meets the demand of EMC to retrieve its place as the hub of Egyptology worldwide, where it allows the museum to link all institutions and museums that have Egyptian collections, as well as those who are conducting scientific research in Egyptian archaeology and antiquities.

Finally, it is a necessity to institute a suitable management strategy for the project in order to accomplish the project within the suggested time frame.

Plans and Figures

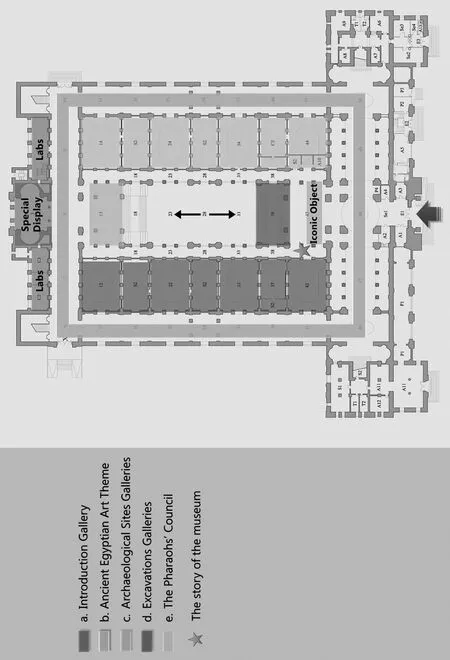

Plan I: The distribution of the suggested themes on the ground floor of the Museum according to the proposed exhibition project. The different grey shades on the plan key refer to the dedicated spaces on the plan.

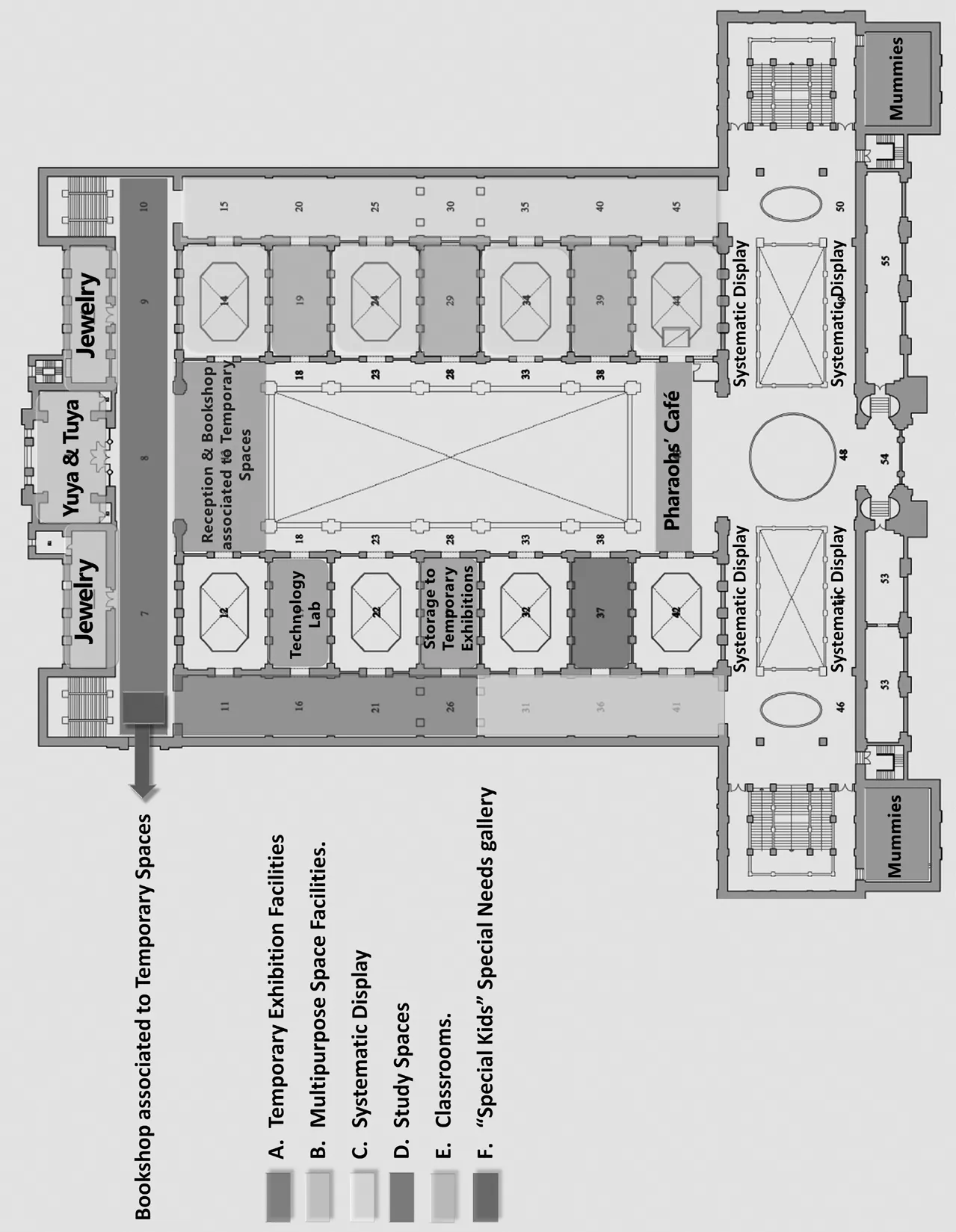

Plan II: The distribution of the suggested themes on the first floor of the Museum according to the proposed exhibition project. The different grey shades on the plan key refer to the dedicated spaces on the plan.

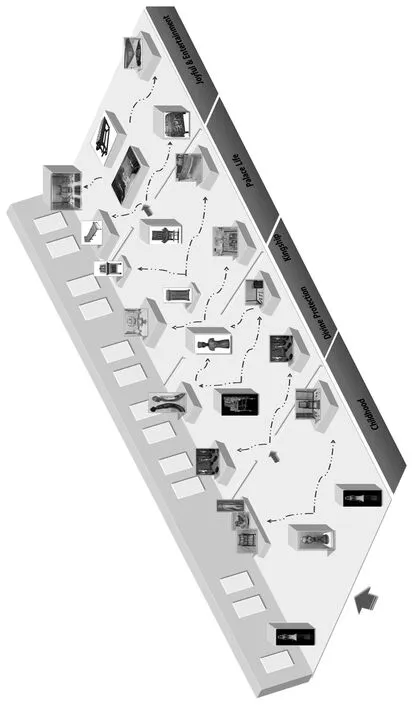

Plan III: The design of the refurbishment of the Tutankhamun Permanent Display, the Egyptian Museum, 2014. An example for a small exhibition project has been implemented at the Egyptian Museum.

Fig. 1: The outdoor façade of the Egyptian Museum Cairo. Courtesy of the Egyptian Museum.

Fig. 2a: An overview of the atrium showing its architectural and current display.

Fig. 2b: The balcony with the panoramic view from the first floor down to the atrium.

Fig. 3: An overview of the west wing of the ground floor with the current chronological display.

Fig. 4: A view of the Old Kingdom galleries R41 & 42, the ground floor.

Fig. 5: An overview of the current display of The Old Kingdom Gallery R 46.

Fig. 6: An overview of the east wing of the ground floor with the current chronological display.

Fig. 7: The animal mummies gallery at the first floor, opened 2002.

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Fig. 11: An overview of the east wing of the first floor with an old display of the Tutankhamun collection.

Fig. 13: Study space of the ceramic galleries at V&A Museum, London. Courtesy of V&A Museum.

Fig. 14: The systematic display at the Greek Roman department, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fig. 15: The ceramic galleries at V&A Museum, London. Courtesy of V&A Museum.

Fig. 16: The ceramic galleries at V&A Museum, London. Courtesy of V&A Museum.

Fig. 17: The systematic display at the Design Museum, Munich. Courtesy of the Design Museum. Die Neue Sammlung – The Design Museum, Mobility. Pinakothek der Moderne,Munich.

Figures 1–11 have been photographed by Mr. Sameh Abdel Mohsen, the photographer of the Egyptian Museum of Cairo; while figures 12 to 17 have been photographed by the author.

Bibliography

Allyn, N., Aubitz, S. and Stern, G. F. 1987.

“Using Archival Materials Effectively in Museum Exhibitions.” In: American Archivist 50: 402–404, accessed under: http://www.americanarchivist.org/doi/pdf/10.17723/aarc.50.3.g5203123461g2208?code=same-site (13.12.2017).

Black, G. 2005.

The Engaging Museum: Developing Museums for Visitor Involvement. London &New York: Routledge.

Blankenberg, N. and Lord, G. 2015.

“Thirsty-two Ways for Museums to Activate Their Soft Power.” In: G. D. Lord and N. Blankenberg (eds.), Cities, Museums and Soft Power. Washington, DC:The AAM Press, 201–239.

Bogle, E. 2013.

Museum Exhibition: Planning and Design. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Carron, G. 2010.

“Strategic Planning; Concept and Rationale.” Working Paper 1 (International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP-UNESCO)): 1–21, accessed under:http://www.iiep.unesco.org/en (13.12.2017).

Casterline, G. F. 1980.

Archives & Manuscripts: Exhibits. Chicago: Society of American Archivists.

Clarke, A. 2002.

Learning through Culture: The DfES Museums and Galleries Education Programme: A Guide to Good Practice. Leicester: Research Centre for Museums and Galleries, University of Leicester.

Crill, R. and Stanley, T. (eds.). 2010.

The Making of the Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: V & A Publications.

Dodd, J. and Sandell, R. 1998.

Building Bridges: Guidance for Museums and Galleries on Development New Audiences. London: Museums and Galleries Commission.

Doyon, W. 2008.

“The Poetics of the Egyptian Museum Practice.” British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 10: 1–37.

El Dorry, M-A. 2011.

“Why Do People Loot? The Case of the Egyptian Revolution.” al-Rai Egypt’s Heritage Review 2: 20–28.

Falk, J. H. 2009.

Identity and the Museum Visitor Experience. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Falk, J. H. and Dierking, L. D. 1992.

The Museum Experience. Washington D.C.: Whalesback.

Falk, J. H., Dierking, L. D. and Adams, M. 2011.

“Living in a Learning Society: Museums and Free-choice Learning.” In:MacDonald 2011, 323–339.

Falk, J. H., Dierking, L. D. and Foutz, S. 2007.

In Principals, In Practice: Museums as Learning Institutions. New York:Altamira Press.

Fladmark, J. M. 2000.

Heritage and Museums: Shaping National Identity. London & New York:Routledge.

Genoways, H. H. and Ireland, L. M. 2003.

Museum Administration: An Introduction. New York: Altamira Press.

Gosden, C. and Marshall, Y. 1999.

“The Cultural Biography of Objects.” World Archaeology 31/2: 169–178.

Clarke, J. 2002.

Supporting Lifelong Learning. vol. I: Perspectives on Learning. London:Routledge Falmer.

Hannan, L., Chatterjee, H. and Duhs, R. 2013.

“Object Based Learning: A Powerful Pedagogy for Higher Education.” In: A.Boddington, J. Boys and C. Speight (eds.), Museums and Higher Education Working Together: Challenges and Opportunities. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing,159–168.

Hawas, Z. 2005.

“New Era for Museums in Egypt.” Museum International (Reshaping of the Heritage Landscape) 57/225–226: 7–23.

Hill, K. (ed.) 2012.

Museums and Biographies: Stories, Objects, Identities. London: Boydell and Brewer.

Hillier, B. and Tazortzi, K. 2011.

“Space Syntax: The Language of Museum Space.” In: McDonald 2011, 282–301.

Hooper-Greenhill, E. 2011.

“Studying Visitors.” In: MacDonald 2011, 363–375.

James, T. G. H. 1982.

Excavating in Egypt. The Egyptian Exploration Society 1882–1982. London: The EES Press.

Jensen, J. T. 2013.

“Improving the Educational Role of Museums in Society.” In: B. I. Lundgaard and J. T. Jensen (eds.), Museums: Social Learning Spaces and Knowledge Producing Processes. Copenhagen: Styrelsen, 26–43.

Illeris, H. 2006.

“Museums and Galleries as Performative Sites for Lifelong Learning:Constructions, Deconstructions, and Reconstructions of Audience Positions in Museum and Gallery Education.” Museum and Society 4/1: 15–26, accessed under: https://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/museumstudies/museumsociety/documents/volumes/2illeris.pdf (12.12.2017).

LaMarre, R. 2014.

“Effective Exhibition Project Management.” In: Lord and Piacente 2014, 379–392.

Liesgang, D. 2014.

“Das Ägyptische Museum Kairo.” Antike Welt, accessed under: http://www.antikewelt.de/index.php/das-agyptische-museum-kairo (01.1.2017).

Lord, B. 2014.

“The Purpose of Museum Exhibitions.” In: Lord and Piacente 2014, 7–22.

Lord, B. and Piacente, P. (eds.). 2014.

Manual of Museum Exhibitions. 2nd ed. New York & Toronto: Rowman &Littlefield.

Lord, G. and Lord, B. 2009.

The Manual of Museum Management. 2nd ed. Lanham, New York & Toronto:Altamira, 53–105.

Kaplan, F. S. 1994.

Museums and the Making of Ourselves: The Role of Objects in National Identity.London & New York: Leicester University Press.

McKenna-Cress, P. and Kamien, J. 2013.

Creating Exhibitions: Collaboration in the Planning, Development, and Design of Innovative Experiences. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

MacDonald, S. (ed.). 2011.

A Companion to Museum Studies. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

MacDonald, S. and Fyfe, G. (eds.). 1996.

Theorizing Museums: Representing Identity and Diversity in a Changing World.Oxford: Blackwell.

Maximea, H. 2014.

“A World of Exhibition Spaces.” In: Lord and Piacente 2014, 99–120.

McLean, F. 2003.

Marketing the Museum. Taylor & Francis e-Library, accessed under: http://gardoonism.com/files/60/root/books/marketing%20the%20museum.pdf(01.01.2017).

Mohamed, W. 2016.

The Passive Discipline: Effective Strategic Planning for the Egyptian Museums of Antiquities. PhD-Dissertation: University Helwan (unpublished).

Mittenthal, R. A. 2002.

Ten Keys to Successful Strategic Planning for Nonprofit and Foundation Leaders.New York: TCC Group, (12 pages), accessed under: http://www.tccgrp.com/pdfs/per_brief_tenkeys.pdf (23.06.2017).

Molineux, K. 2014.

“Permanent Collection Displays.” In: Lord and Piacente 2014, 121–132.

Paris, K. 2003.

Strategic Planning in the University. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin (23 pages), accessed under: http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/u-planning-office/documents/other-strategic-planning/paris-2003_strat-plan-in-u.pdf (23.06.2017).

Paris, S. G. 2002.

Perspectives on Object-Centered Learning in Museums. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Piacente, M. 2014.

“Interpretive Planning.” In: Lord and Piacente 2014, 253–263.

Rashed, M. Gamal. 2014a.

“Cairo Major Museums Conflict in Discussions.” In: Archaeological Sources and Resources in the Context of Museums. The 31st CIPEG Annual Meeting,Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, 26–29 Aug., accessed under: http://www.egyptologyforum.org/CIPEG/CIPEG_2014_program.pdf (01.06.2017).

—— 2014b.

“‘Ankh-Wedja-Senb,’ Life, Health and Prosperity for Tutankhamun.” Antike Welt 1/15: 1–21, accessed under: http://www.antikewelt.de/index.php/ankh-w-da-snb(01.11.2017).

—— 2015a.

“Cairo and its Museums: From Multiculturalism to Leadership in Sustainable Development.” In: G. D. Lord and N. Blankenberg (eds.), Cities, Museums and Soft Power. Washington, DC: The AAM Press, 165–172.

—— 2015b.

“Ausblick auf eine grosse Ära für Museen in Ägypten: Das Grand Egyptian Museum.” Antike Welt 2/15: 84–86.

—— 2015c.

“The Future Permanent Display of the Egyptian Museum of Cairo. The Concept and Exhibition Program.” In: From Historicism to the Multimedia Age. Content– Concept – Design of the Egyptian Museums and Collections. The 32nd CIPEG Annual Meeting, Staatliche Museum, Munich, 1st–4th September, accessed under: https://www.academia.edu/22081816/The_new_Permanent_Display_of_the_Egyptian_Museum_of_Cairo_The_Concept_and_Exhibition_Program_in_CIPEG_32_Munich_2015 (01.06.2017).

—— 2016a.

“Museen in Ägypten: Herausorderungen und Chancen.” Antike Welt 4/16: 55–59.—— 2016b.

“The Museums in Egypt after the 2011 Revolution.” Museums International(Museums and Heritage in the Times of Political Change) 67/265–268: 125–130.—— 2017.

“The Museums of Egypt Speak for Whom?” Comité international pour l’égyptologie Journal 1: 1–11, accessed under: https://doi.org/10.11588/cipeg.2017.1.40324 (01.11.2017).

Salving, J. C. and Fleming, M. 2013.

“Social Inclusion and Interdisciplinarity Learning Space.” In: B. I. Lundgaard and J. T. Jensen (eds.), Museums: Social Learning Spaces and Knowledge Producing Processes. Copenhagen: Styrelsen, 134–171.

Salway, O. 2010.

“The Design of the Jameel Gallery.” In: R. Crill and T. Stanley (eds.), The Making of the Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum.London: V & A Publications, 76–101.

Sandell R. and Janes R. 2007.

Museum Management and Marketing. London & New York: Routledge.

Shapiro, J. 2001.

Strategic Planning Toolkit. Washington: CIVICUS, 1–53, accessed under: http://www.civicus.org/view/media/Strategic%20Planning.pdf (23.06.2017).

Simon, N. 2010.

The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz, CA: Museum 2.0.

Stevenson, A. 2015.

“Egyptian Archaeology and the Museum.” Oxford University Handbook for Archaeology Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1–21, accessed under: http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935413.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199935413-e-25 (13.12.2017).

Thomas, N. 2010.

“The Museum as Method.” Museum Anthropology 33/1: 6–10.

The Revival of the Egyptian Museum. 2013.

The Egyptian Museum, an Official Document, Cairo. [Official Document,29 pages], accessed under: http://www.kairo.diplo.de/contentblob/3926336/Daten/3348650/ku_aegyptisches_museum_01.pdf (01.01.2017).

Vrontis, D. and Thrassou, A. 2006.

“Situation Analysis and Strategic Planning: An Empirical Case Study in the UK Beverage Industry.” Innovative Marketing 2/2: 134–151, accessed under: http://businessperspectives.org/journals_free/im/2006/im_en_2006_02_Vrontis.pdf(01.01.2017).

UNESCO Culture. 2012.

Egyptian Museums One Year after the Revolution. Paris: UNESCO Online,accessed under: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/single-view/news/egyptian_museums_one_year_after_the_revolution#.VqYsBvl96M8(01.01.2017).

Yousuf, N. 2010.

“Gallery Interpretation.” In: R. Crill and T. Stanley (eds.), The Making of the Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: V & A Publications, 125–138.

Wilk, C. (ed.). 2004.

The Making of the British Galleries at the V & A: A Study in Museology. London:V & A Publications.

Wright, G. A. N. et al. 2007.

Strategic Business Planning for Market-led Financial Institutions Toolkit. Version 0707, MicroSave, accessed under: http://www.setoolbelt.org/resources/934(01.01.2017).

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

Journal of Ancient Civilizations的其它文章

- ABSTRACTS

- BOOK REVIEW

- GLOBAL HISTORY, ENTANGLED AREAS, CULTURAL CONTACTS –AND THE ANCIENT WORLD1

- DRAMATIC ELEMENTS IN POLYBIUS’ GENERAL HISTORY:AN ANALYSIS BASED ON THE MODEL OF THE CONNECTIVITY OF THE ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN WORLD

- “MY PUTREFACTION IS MYRRH:”THE LEXICOGRAPHY OF DECAY, GILDED COFFINS,AND THE GREEN SKIN OF OSIRIS

- Editors’ Note