植物呼吸释放CO2碳同位素变化研究进展

2018-06-07钟尚志崔海莹

柴 华,钟尚志,崔海莹,李 杰,孙 伟

东北师范大学草地科学研究所植被生态科学教育部重点实验室, 长春 130024

碳循环是最重要的生物地球化学循环之一[1- 2]。随着CO2浓度升高引起的气候变化,碳循环过程及其与气候变化之间反馈调节机制成为生态学研究的一个热点[3- 4]。稳定性碳同位素技术作为探究碳循环过程的重要手段,在不同时间和空间尺度生态与环境问题研究中得到广泛应用[5- 7]。同时,探究碳循环不同过程稳定性碳同位素组成、变化趋势及其控制机制是当前生态学研究的另一个热点,有助于研究者更好地将碳同位素技术应用于生态系统碳循环过程研究[8]。

植物在生态系统与大气CO2交换过程中起到非常重要的作用[9]。植物通过光合作用吸收大气中的CO2,一部分光合产物储存在生物体中以维持自身的生长、繁殖等生命活动,另一部分通过植物的呼吸作用返回到大气中。在此过程中,植物通过光合作用和呼吸作用对近地面大气中CO2的稳定性碳同位素组成(13CO2丰度)产生影响。其中,光合作用增加了近地面大气中的13CO2丰度,而呼吸作用则趋于稀释空气中的13CO2丰度[10]。

植物呼吸释放CO2的碳同位素组成(δ13CR)受环境变化导致的光合判别和光合产物同位素组成影响,与大气中的13CO2存在显著差异[11- 13]。光合产物后续代谢过程的同位素分馏(isotope fractionation)也能够影响呼吸底物的碳同位素组成和植物不同器官呼吸释放的CO2碳同位素组成,并通过改变碳同位素通量的时空变化影响生态系统呼吸CO2的碳同位素组成,最终影响基于稳定性同位素技术的碳通量估测[14-15]。因此,植物δ13CR的碳同位素信号不仅有助于探究生态系统与大气的碳通量[16-17],区分生态系统呼吸[18-19],也能反映植物的生理过程[15]、碳分配方式[20]及植物应对环境变化的适应策略[21- 22]。

目前,国际上关于植物δ13CR的碳同位素组成、短期变化特征及其潜在生理机制已开展了一系列的研究工作[8,14,23],提出了底物同位素控制、呼吸中间产物分配、光照增强暗呼吸(LEDR, light-enhanced dark respiration)、呼吸过程同位素分馏变化等生理生态机制,但内在机制尚不清楚。本文通过概述国内外植物呼吸释放13CO2短期动态变化的研究概况,分析影响植物δ13CR短期变化的潜在机制,旨在推动稳定性碳同位素技术在生态系统碳循环研究中的应用。

1 植物呼吸释放13CO2短期动态变化研究概况

近年来,国内外学者针对植物δ13CR短期动态变化开展了一系列研究工作,发现植物δ13CR短期动态存在同种植物不同器官以及植物功能群差异。植物叶片暗呼吸释放CO2碳同位素组成有较大的变异性,变化范围为:(-31.9±0.3)‰—(-13.8±1.0)‰,昼夜变化幅度的最大值为11.5‰;树干/茎暗呼吸释放CO2碳同位素组成变化范围为:(-32.1±0.8)‰—(-21.2±0.3)‰,昼夜变化幅度的最大值为4.0‰;植物根系暗呼吸释放CO2碳同位素组成变化范围为:(-33.3±0.5)‰—(-16.3±1.9)‰,昼夜变化幅度的最大值为5.4‰[23]。

不同功能群植物δ13CR昼夜变化幅度研究较少,且结果存在不一致性。Priault等[3]通过对16种植物叶片暗呼吸研究发现,不同功能群植物存在δ13CR昼夜变化差异:慢速生长和芳香类植物的δ13CR有昼夜变化,幅度范围为1.4‰—7.9‰;草本、快速生长植物δ13CR则没有显著的昼夜变化。Cui等[24]通过对22种植物叶片暗呼吸研究发现,C3植物和C4植物δ13CR夜间变化幅度差异不显著,并且δ13CR夜间变化幅度在木本植物、杂类草和禾草之间也没有显著的差异。植物δ13CR的功能群差异需要深入研究。

植物暗呼吸释放CO2碳同位素组成与呼吸底物碳同位素组成的相关性研究结果并不一致:部分研究表明,植物δ13CR与呼吸底物碳同位素组成具有相关性,但植物δ13CR的变化幅度大于呼吸底物碳同位素组成的变化范围[17, 25- 29];也有一些研究表明,植物呼吸底物碳同位素组成并没有显著的昼夜变化,但植物δ13CR却有显著的变化[28,30-33];此外,也有研究表明植物δ13CR的变化幅度与呼吸底物的碳同位素组成呈负相关关系[27,34]。植物自养呼吸底物十分复杂,可以分为快速周转和慢速周转碳水化合物两类,其构成和稳定性碳同位素组成均有差异,很难在提取过程中将二者区分开,这也是导致植物δ13CR与底物碳同位素组成之间关系不确定的原因之一[35]。总体而言,目前对植物叶片δ13CR与呼吸底物碳同位素组成关系研究较多,但缺乏对植物其他特定组织的研究,如树干、茎、根系呼吸释放CO2碳同位素组成及其潜在生理机制的研究。

迄今为止,国内关于植物δ13CR短期动态变化的研究鲜有报道。近年来,植物δ13CR的动态变化及其调控机制是生态学的研究热点之一,但国内关于此方面的研究较少。因此,亟需加强我国关于植物δ13CR碳同位素组成及其潜在呼吸代谢机制的研究。

2 植物δ13CR短期变化的驱动机制

碳从大气经由植物叶片、茎、根系和土壤返回大气过程中涉及众多物理和生化过程,与之相关的同位素分馏和同位素判别(isotope discrimination)效应显著改变13C丰度。

Farquhar等[36]对同位素分馏和同位素判别给出定义:“同位素分馏”是指某一反应过程中同位素以不同的比例分配到不同的物质中;而“同位素判别”是指某一反应中或某催化剂由于同位素在质量上的差异,使其对重同位素有识别和排斥的作用,致使产物的重同位素含量减少的现象。同位素分馏表示的是反应物同位素组成改变的效果,而同位素判别表示的是造成反应物同位素组成改变的一种过程或原因[37]。受生长环境、遗传特性、功能群差异影响,植物光合、呼吸过程相关同位素效应存在变异,导致呼吸释放CO2碳同位素组成和短期变化幅度存在差异。已有研究结果表明,这些因素对植物δ13CR的作用并不是单一进行的,而是共同影响并可能存在相互作用[3,23]。

2.1 光合作用及其产物的同位素效应

2.1.1 光合碳同位素效应

植物通过光合作用合成13C贫化的含碳化合物,这些光合产物是植物呼吸的主要底物。因此,光合碳固定过程中,碳同位素分馏能够通过改变光合产物稳定性碳同位素组成,进而影响植物δ13CR及其变化幅度。植物叶片光合碳固定过程对于13C的同位素分馏主要包含两个过程:(1)大气中的CO2经由植物气孔向叶片扩散时发生同位素分馏(4.4‰)。12C、13C在化学性质上没有明显的差别,但由于质量上的细微差异使得大气中13CO2的扩散速率比12CO2慢,植物优先吸收12CO2而排斥13CO2。因此,进入叶肉细胞间隙的CO2其13C丰度低于大气CO2;(2)CO2同化过程中,二磷酸核酮糖羧化酶(ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase, RuBPCase, 29‰)和磷酸烯醇式丙酮酸羧化酶(phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, PEPCase, 5.7‰)对稳定性碳同位素存在分馏作用,溶解在细胞质中的12CO2优先通过酶的作用结合为磷酸甘油酸,因此合成的光合产物13C贫化[10]。

光合碳同位素判别仅在白天发生,但其不仅影响白天δ13CR,也可能影响夜晚δ13CR。植物夜晚呼吸利用底物主要是日间光合所积累的淀粉,淀粉在合成和分解过程中存在一定的时间差异,清晨和上午合成的淀粉处于淀粉颗粒的核心,通常在凌晨时分被分解利用[32,38]。白天光照、温度等环境条件变化导致的光合判别变化会通过影响淀粉颗粒不同部位稳定性碳同位素组成进而影响夜晚δ13CR。然而,δ13CR的昼夜变化并不能完全由光合碳同位素判别解释[23]。光合产物后续代谢过程同样存在潜在的同位素判别,例如,暗呼吸和光合产物由叶片向植物下游组织输出过程亦伴随同位素判别[39]。基于同位素模型预测研究发现,夜晚蓖麻(RicinuscommunisL.)的韧皮部和菜豆(PhaseolusvulgarisL.)、林烟草(NicotianasylvestrisSpeg.)、向日葵(HelianthusannuusL.)的叶片糖类δ13C值的变异度远大于预计的仅受光合判别作用的值[29,40]。因此,在研究植物δ13CR的短期变化时,既要考虑光合产物形成过程的同位素判别,又不能忽视光合产物后续代谢过程同位素效应的作用。与其他器官相比,叶片暗呼吸释放CO2呈13C富集态势,而叶片的δ13C值却低于植物其他器官,光合产物后续代谢过程同位素判别可以解释这种普遍观测到的植物器官间碳同位素差异现象[39]。

2.1.2 光合产物后续代谢过程同位素分馏

在卡尔文循环中,代谢分支点以及磷酸丙糖(triose phosphate, TP, 光合作用合成的最初糖类)向细胞溶质输出或继续在卡尔文循环中使用均存在碳同位素分馏[41]。在植物叶绿体中,卡尔文循环形成磷酸丙糖,经过各种酶的催化形成淀粉。在此过程中由于醛缩酶(aldolase)同位素效应的影响,使得淀粉中13C的丰度高于可溶性糖[42-43],而剩余的13C贫化的磷酸丙糖合成蔗糖从叶绿体中输出,进而改变呼吸底物的13C组成。同时,白天光合作用积累的淀粉在夜晚分解用于植物呼吸代谢和向其他器官的光合产物输出,造成叶片和植物韧皮部输出糖类δ13C值的昼夜差异,白天蔗糖中13C贫化,夜晚蔗糖中13C富集[29,40]。植物韧皮部的蔗糖混合了具有不同代谢历史和滞留时间的蔗糖分子[25],其δ13C值取决于植物最初积累淀粉的δ13C值,以及糖类在植物茎部由上至下的传输距离[23]。总体来讲,糖类在植物由上往下的传输过程中,由于同位素分馏的作用,使得不同类型和不同部位的呼吸底物δ13C值及其日变化幅度存在差异,从而影响植物茎和根呼吸释放CO2的δ13CR值及其日变化幅度。

2.2 呼吸碳同位素分馏

由于植物呼吸代谢过程中细胞、组织以及植物类型的不同,导致不同的代谢途径呼吸释放的CO2同位素组成存在差异。植物呼吸过程碳同位素分馏包括糖类分子结构上13C不均衡分布(non-statistical13C distribution)导致的裂解分馏、呼吸酶的同位素效应、次生代谢过程中的同位素分馏[10]。

2.2.1 裂解分馏

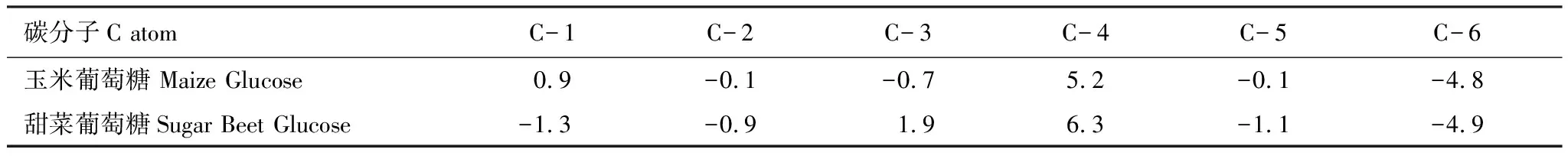

由于醛缩酶的同位素分馏效应,导致葡萄糖分子中13C的不均匀分布,与葡萄糖分子整体13C丰度相比,其中C- 3和C- 4富含13C,而其他位置的碳则呈13C贫化趋势(表1)[43-45]。不同光合途径植物在葡萄糖分子13C分布不均匀性上存在差异,主要是因为光呼吸导致二磷酸核酮糖(RuBP)分子内部结构存在差异,在光合作用下二磷酸核酮糖还原为磷酸丙糖,最终合成糖类物质[45]。

表1 葡萄糖分子内部13C的不均衡分布(不同位置C原子相对于葡萄糖分子δ13C平均值的差值)

C- 1:葡萄糖分子中第一位碳原子,C- 2:葡萄糖分子中第二位碳原子,后同,数据来源于Rossmann等[44]

在糖酵解过程中,葡萄糖首先活化为1,6-二磷酸果糖,然后裂解为3-磷酸甘油醛和磷酸二羟丙酮,接着3-磷酸甘油醛氧化释放能量,并最终生成丙酮酸。在此过程中,从富含13C葡萄糖的C- 3和C- 4转化为C- 1的丙酮酸,在丙酮酸脱氢酶(PDH)作用下释放富含13C的CO2。含有相对13C贫化碳分子的乙酰辅酶A(Acetyl CoA)既可以进入柠檬酸循环,经过脱羧作用,分解产生ATP(adenosine triphosphate),又可以被用于合成次生代谢产物[3]。当所有乙酰辅酶A均用于呼吸作用时,所产生CO2的13C丰度与底物葡萄糖一致;当部分乙酰辅酶A用于合成次生代谢产物时,呼吸释放CO2的13C丰度则高于底物葡萄糖[23](图1)。很多研究发现植物暗呼吸释放CO2的13C丰度高于其呼吸底物的13C丰度,并归因于乙酰辅酶A未完全用于呼吸分解所导致的同位素分馏[46-50]。

Priault等[3]通过丙酮酸13C标记研究表明,在丙酮酸脱羧反应和柠檬酸循环中均存在碳同位素分馏。灌木植物欧洲半日花(HalimiumhalimifoliumL.)在丙酮酸脱氢酶的作用下,释放富含13C的CO2,而剩余的丙酮酸进入次生代谢的碳通量超过进入柠檬酸循环的碳通量数倍,致使δ13CR的日变化幅度增加;而快速生长的草本植物三角紫叶酢浆草(OxalistriangularisA. St-Hil.)的次生代谢活动和柠檬酸循环都保持低的活性,因此δ13CR的日变化幅度不明显(图1)。

图1 植物呼吸代谢中间产物利用对暗呼吸δ13CR的影响Fig.1 Major expected fluxes of respiratory substrates explaining δ13CR of dark-respired CO2 depending on the respiratory energy demand PDH: 丙酮酸脱氢酶 pyruvate dehydrogenase; KC: 柠檬酸循环 Krebs Cycle; 粗体C代表含有高丰度的13C,阴影部分表示主要的呼吸底物的通量,黑色箭头代表碳的通量,改绘自Priault等[3]

2.2.2PEPCase对植物释放CO2的再固定

PEPCase能够催化植物体内呼吸释放CO2的再固定(CO2refixation),该过程伴随碳同位素判别效应(5.7‰)[36],对植物非光合组织呼吸释放CO2碳同位素组成有重要影响。所有植物器官中均存在PEPCase[51-52],不同器官PEPCase酶活性的差异会导致同位素呼吸分馏上存在差异[53]。由于PEPCase的作用使得生成的有机物质中13C丰度高于未被固定CO2的丰度,同时降低了由植物向大气的CO2呼吸释放通量。理论上PEPCase酶活性与植物δ13CR值呈正相关关系,但研究表明植物根、茎的PEPCase与δ13CR值并没有相关性[23]。因此,PEPCase可能并不是导致植物δ13CR变化的关键因素。

2.3 光照增强暗呼吸

当植物叶片从光照条件立即转变为黑暗条件时,呼吸释放CO2量呈显著增加趋势,这种现象被称为光照增强暗呼吸(LEDR)[54]。LEDR不仅导致植物叶片呼吸释放CO2量的增加,也影响呼吸释放CO2的碳同位素组成,δ13CR值表现为先增加后降低的趋势,植物叶片δ13CR的日变化幅度增加,δ13CR值增加的时间一般会持续5—20分钟[55-56]。LEDR现象对叶片暗呼吸释放CO2碳同位素组成影响程度依赖于光照强度,一般随着光强的增加而增加[54, 57-59]。在光照条件下,植物自养器官中与糖酵解和柠檬酸循环相关酶的活性受到抑制[60-61],导致柠檬酸循环处于非闭合的状态[62-63],而苹果酸则在PEPCase的作用下得到积累。当植物叶片由光照条件转入黑暗条件后,呼吸酶抑制作用解除,催化苹果酸分解,释放富含13C的C- 4,导致呼吸释放CO2的碳同位素组成改变,LEDR的瞬时效应在自然条件下不仅出现在白天,晴天日落后也会持续约90分钟,显著影响夜晚初期生态系统呼吸释放CO2同位素组成[64]。因此,采用容器收集植物叶片呼吸时需要慎重确定培养时间[3]。

2.4 环境因素对植物δ13CR短期变化的影响

环境因素能够影响植物δ13CR及其变化幅度。DeNiro和Epstein[65]的研究发现夜间温度的变化会通过影响呼吸酶的活性改变13C/12C分馏,促使叶片δ13CR发生变化。随着叶片温度的升高,呼吸底物由碳水化合物转为脂肪(13C相对贫化),导致植物叶片呼吸CO2的δ13CR值持续下降[47]。Schnyder和Lattanzi[66]的研究也表明生长在高温环境中(25℃/23℃,白天/夜晚)的黑麦草(LoliumperenneL.)其根系呼吸底物和呼吸释放CO2的δ13C值(-21.7‰、-24.9‰)均高于生长在低温环境中的δ13C值(15℃/14℃,白天/夜晚)(-22.8‰、-28.3‰)。

水分条件会通过影响光合碳同位素判别,改变呼吸底物的δ13C值,使植物呼吸CO2的δ13CR发生改变[67]。叶片内外水蒸汽压差的增加通常会降低气孔导度[68],使大气CO2经气孔进入叶片的量减少,导致胞间CO2和空气CO2分压比(Pi/Pa)降低,同位素判别会随着Pi/Pa的降低而降低,同时增加了13C的同化,因此植物呼吸CO2的δ13CR值和日变化幅度均会发生改变[36]。在干旱胁迫下,水分条件的限制降低了气孔导度和Pi/Pa的日变化幅度,导致光合碳同位素判别日变化幅度不明显[69],并且干旱胁迫会显著的降低呼吸分馏,影响与呼吸底物相关联的植物呼吸δ13CR值[47-48]。例如,在美国亚利桑那州沙漠生态系统的研究结果表明,干旱季节叶片呼吸δ13CR值显著高于雨季[32]。

不同的生长环境也会影响植物δ13CR值,Klumpp等[50]研究发现,生长在低密度下的向日葵δ13CR值高于生长在高密度下的δ13CR值。环境因素对植物呼吸δ13CR值的影响往往表现为综合作用,不同时间尺度(昼夜、季节性)环境变化会改变与呼吸底物相关联的叶片暗呼吸δ13CR的数值和日变化程度[19,33]。例如,Sun等[70-71]通过探究不同植被类型(C3和C4)δ13CR对于环境变化的响应发现,季节性的环境变化不仅影响呼吸代谢底物碳同位素值,也能够通过影响底物量进而影响呼吸代谢中间产物乙酰辅酶A的利用,最终改变δ13CR值和日变化幅度。此外,植物在受到来自自然条件的胁迫时(例如凋萎或衰老、长期处于黑暗条件),会发生呼吸底物的转变[19],呼吸底物类型(可溶性糖、淀粉、脂类、氨基酸)间在碳同位素组成上存在差异,进而对δ13CR产生影响[35,49]。

3 结论与展望

植物δ13CR的短期动态变化能够反映植物碳分配方式、碳代谢生理过程、植物与环境相互作用等重要生理生态过程,探究植物呼吸释放碳同位素组成变化有助于推进陆地生态系统碳循环的研究。不同植物类型以及植物的不同器官δ13CR值均存在差异。多数研究表明植物不同部位δ13CR值差异及变化幅度趋势一致,表现为:叶片δ13CR>根系δ13CR>树干/茎δ13CR,但植物暗呼吸释放的δ13CR与呼吸底物的变化趋势并不一致。同位素效应、呼吸底物的供给和消耗、糖类分子13C的不均匀分布、碳代谢相关酶的活性、LEDR、植物的遗传特性及外部环境等因素均可以改变植物δ13CR值及其变化幅度。总体上说,导致植物δ13CR发生变化的原因可以归纳为以下几点:(1)植物呼吸底物的δ13C值发生变化;(2)植物在不同时期利用的呼吸底物不同,而这些呼吸底物中δ13C值存在差异;(3)植物呼吸代谢中对中间产物利用方式的变化,导致植物δ13CR值发生变化。

近年来,随着科学技术的发展,为研究植物暗呼吸碳同位素组成的动态变化及内在控制机制提供了广阔的前景。随着稳定性碳同位素标记技术的成熟,利用13C标记进而追踪植物同化和释放的碳同位素,可直接、有效的定期监测植物不同器官及其暗呼吸碳同位素组成变化趋势及对环境变化的响应。稳定性同位素质谱仪(Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer, IRMS)是测定植物暗呼吸释放CO2碳同位素组成的较为成熟的方法,具有样品用量少、测量精确性高等优点。但设备存在结构复杂,体积大,造价较高,且测试样品容易受到污染等缺陷。激光吸收光谱法(Laser Absorption Spectroscopy, LAS)、特定化合物同位素分析(Compound Specific Isotope Analysis, CSIA)、核磁共振技术(Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, NMR)、纳米二次离子质谱技术(Nano-scale Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometer, Nano SIMS)具有快速测定、高敏感度、高精确度、增加可重复性等优点,为研究植物暗呼吸和内在控制机制提供了更为多样化的手段。

关于导致植物暗呼吸发生变化的原因已有了较多的研究,但内在调控机理尚不明晰。在未来的研究中,研究者可关注以下几方面的研究:(1)植物暗呼吸δ13CR值对外部环境变化及植物特性(例如:叶肉细胞导度)的响应;(2)植物同化产物δ13C值与呼吸释放δ13CR的比较及其在不同时空尺度的动态变化;(3)不同功能群植物暗呼吸δ13CR的变化及其与呼吸代谢活动的关系;(4)不同生态系统碳同位素通量以及对生态系统呼吸δ13CR的贡献率。

研究植物δ13CR有助于我们更好地了解植物尺度碳的流动,以及植物与生态系统的碳交换。目前,国际上已有较多关于δ13CR值短期变化的研究,但我国关于此方面的研究鲜有报道,以期通过本文增进国内关于植物呼吸碳同位素领域研究的了解,推动相关研究工作的深入开展。

参考文献(References):

[1] Falkowski P, Scholes R J, Boyle E, Canadell J, Canfield D, Elser J, Gruber N, Hibbard K, Högberg P, Linder S, Mackenzie F T, Moore III B, Pedersen T, Rosenthal Y, Seitzinger S, Smetacek V, Steffen W. The global carbon cycle: a test of our knowledge of earth as a system. Science, 2000, 290(5490): 291- 296.

[2] Scholze M, Kaminski T, Knorr W, Blessing S, Vossbeck M, Grant J P, Scipal K. Simultaneous assimilation of SMOS soil moisture and atmospheric CO2in-situ observations to constrain the global terrestrial carbon cycle. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2016, 180: 334- 345.

[3] Priault P, Wegener F, Werner C. Pronounced differences in diurnal variation of carbon isotope composition of leaf respired CO2among functional groups. New Phytologist, 2009, 181(2): 400- 412.

[4] IPCC. Climate Change 2013: the Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

[5] Yakir D, da Silveira Lobo Sternberg L. The use of stable isotopes to study ecosystem gas exchange. Oecologia, 2000, 123(3): 297- 311.

[6] Ostle N, Ineson P, Benham D, Sleep D. Carbon assimilation and turnover in grassland vegetation using aninsitu13CO2pulse labelling system. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 2000, 14(15): 1345- 1350.

[7] 易现峰, 张晓爱. 稳定性同位素技术在生态学上的应用. 生态学杂志, 2005, 24(3): 306- 314.

[8] Bowling D R, Pataki D E, Randerson J T. Carbon isotopes in terrestrial ecosystem pools and CO2fluxes. New Phytologist, 2008, 178(1): 24- 40.

[9] Beer C, Reichstein M, Tomelleri E, Ciais P, Jung M, Carvalhais N, Rödenbeck C, Arain M A, Baldocchi D, Bonan G B, Bondeau A, Cescatti A, Lasslop G, Lindroth A, Lomas M, Luyssaert S, Margolis H, Oleson K W, Roupsard O, Veenendaal E, Viovy N, Williams C, Woodward F I, Papale D. Terrestrial gross carbon dioxide uptake: global distribution and covariation with climate. Science, 2010, 329(5993): 834- 838.

[10] 林光辉. 稳定同位素生态学. 北京: 高等教育出版社, 2013.

[11] Fung I, Field C B, Berry J A, Thompson M V, Randerson J T, Malmström C M, Vitousek P M, Collatz G J, Sellers P J, Randall D A, Denning A S, Badeck F, John J. Carbon 13 exchanges between the atmosphere and biosphere. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 1997, 11(4): 507- 533.

[12] Pataki D E, Ehleringer J R, Flanagan L B, Yakir D, Bowling D R, Still C J, Buchmann N, Kaplan J O, Berry J A. The application and interpretation of Keeling plots in terrestrial carbon cycle research. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 2003, 17(1): 1022.

[13] Mortazavi B, Chanton J P, Smith M C. Influence of13C-enriched foliage respired CO2onδ13C of ecosystem-respired CO2. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 2006, 20(3): GB3029.

[14] Ghashghaie J, Badeck F W. Opposite carbon isotope discrimination during dark respiration in leaves versus roots-a review. New Phytologist, 2014, 201(3): 751- 769.

[15] Ghashghaie J, Badeck F W, Lanigan G, Nogués S, Tcherkez G, Deléens E, Cornic G, Griffiths H. Carbon isotope fractionation during dark respiration and photorespiration in C3plants. Phytochemistry Reviews, 2003, 2(1/2): 145- 161.

[16] Knohl A, Werner R A, Brand W A, Buchmann N. Short-term variations inδ13C of ecosystem respiration reveals link between assimilation and respiration in a deciduous forest. Oecologia, 2005, 142(1): 70- 82.

[17] Kodama N, Barnard R L, Salmon Y, Weston C, Ferrio J P, Holst J, Werner R A, Saurer M, Rennenberg H, Buchmann N, Gessler A. Temporal dynamics of the carbon isotope composition in aPinussylvestrisstand: from newly assimilated organic carbon to respired carbon dioxide. Oecologia, 2008, 156(4): 737- 750.

[18] Bowling D R, Tans P P, Monson R K. Partitioning net ecosystem carbon exchange with isotopic fluxes of CO2. Global Change Biology, 2001, 7(2): 127- 145.

[19] Unger S, Máguas C, Pereira J S, Aires L M, David T S, Werner C. Disentangling drought-induced variation in ecosystem and soil respiration using stable carbon isotopes. Oecologia, 2010, 163(4): 1043- 1057.

[20] Damesin C, Lelarge C. Carbon isotope composition of current-year shoots fromFagussylvaticain relation to growth, respiration and use of reserves. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2003, 26(2): 207- 219.

[21] Keitel C, Adams M A, Holst T, Matzarakis A, Mayer H, Rennenberg H, Geßler A. Carbon and oxygen isotope composition of organic compounds in the phloem sap provides a short-term measure for stomatal conductance of European beech (FagussylvaticaL.). Plant, Cell & Environment, 2003, 26(7): 1157- 1168.

[22] Pate J, Arthur D.δ13C analysis of phloem sap carbon: novel means of evaluating seasonal water stress and interpreting carbon isotope signatures of foliage and trunk wood ofEucalyptusglobulus. Oecologia, 1998, 117(3): 301- 311.

[23] Werner C, Gessler A. Diel variations in the carbon isotope composition of respired CO2and associated carbon sources: a review of dynamics and mechanisms. Biogeosciences, 2011, 8(9): 2437- 2459.

[24] Cui H Y, Wang Y B, Jiang Q, Chen S P, Ma J Y, Sun W. Carbon Isotope composition of nighttime leaf-respired CO2in the agricultural-pastoral zone of the Songnen Plain, Northeast China. PLoS One, 2015, 10(9): e0137575.

[25] Brandes E, Kodama N, Whittaker K, Weston C, Rennenberg H, Keitel C, Adams M A, Gessler A. Short-term variation in the isotopic composition of organic matter allocated from the leaves to the stem ofPinussylvestris: effects of photosynthetic and postphotosynthetic carbon isotope fractionation. Global Change Biology, 2006, 12(10): 1922- 1939.

[26] Brandes E, Wenninger J, Koeniger P, Schindler D, Rennenberg H, Leibundgut C, Mayer H, Gessler A. Assessing environmental and physiological controls over water relations in a Scots pine (PinussylvestrisL.) stand through analyses of stable isotope composition of water and organic matter. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2007, 30(1): 113- 127.

[27] Gessler A, Keitel C, Kodama N, Weston C, Winters A J, Keith H, Grice K, Leuning R, Farquhar G D.δ13C of organic matter transported from the leaves to the roots inEucalyptusdelegatensis: short-term variations and relation to respired CO2. Functional Plant Biology, 2007, 34(8): 692- 706.

[28] Gessler A, Tcherkez G, Peuke A D, Ghashghaie J, Farquhar G D. Experimental evidence for diel variations of the carbon isotope composition in leaf, stem and phloem sap organic matter inRicinuscommunis. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2008, 31(7): 941- 953.

[29] Werner C, Wegener F, Unger S, Nogués S, Priault P. Short-term dynamics of isotopic composition of leaf-respired CO2upon darkening: measurements and implications. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 2009, 23(16): 2428- 2438.

[30] Wegener F, Beyschlag W, Werner C. The magnitude of diurnal variation in carbon isotopic composition of leaf dark respired CO2correlates with the difference betweenδ13C of leaf and root material. Functional Plant Biology, 2010, 37(9): 849- 858.

[31] Rascher K G, Máguas C, Werner C. On the use of phloem sapδ13C as an indicator of canopy carbon discrimination. Tree Physiology, 2010, 30(12): 1499- 1514.

[32] Sun W, Resco V, Williams D G. Diurnal and seasonal variation in the carbon isotope composition of leaf dark-respired CO2in velvet mesquite (Prosopisvelutina). Plant, Cell & Environment, 2009, 32(10): 1390- 1400.

[33] Hymus G J, Maseyk K, Valentini R, Yakir D. Large daily variation in13C-enrichment of leaf-respired CO2in twoQuercusforest canopies. New Phytologist, 2005, 167(2): 377- 384.

[34] Gessler A, Tcherkez G, Karyanto O, Keitel C, Ferrio J P, Ghashghaie J, Kreuzwieser J, Farquhar G D. On the metabolic origin of the carbon isotope composition of CO2evolved from darkened light-acclimated leaves inRicinuscommunis. New Phytologist, 2009, 181(2): 374- 386.

[35] Nogués S, Tcherkez G, Cornic G, Ghashghaie J. Respiratory carbon metabolism following illumination in intact French bean leaves using13C/12C isotope labeling. Plant Physiology, 2004, 136(2): 3245- 3254.

[36] Farquhar G D, Ehleringer J R, Hubick K T. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology, 1989, 40: 503- 537.

[37] 林光辉, 柯渊. 稳定同位素技术与全球变化研究//李博. 现代生态学讲座. 北京: 科学出版社, 1995.

[38] Zeeman S C, Smith S M, Smith A M. The diurnal metabolism of leaf starch. Biochemical Journal, 2007, 401(1): 13- 28.

[39] Cernusak L A, Tcherkez G, Keitel C, Cornwell W K, Santiago L S, Knohl A, Barbour M M, Williams D G, Reich P B, Ellsworth D S, Dawson T E, Griffiths H G, Farquhar G D, Wright I J. Why are non-photosynthetic tissues generally13C enriched compared with leaves in C3plants? Review and synthesis of current hypotheses. Functional Plant Biology, 2009, 36(3): 199- 213.

[40] Tcherkez G, Farquhar G, Badeck F, Ghashghaie J. Theoretical considerations about carbon isotope distribution in glucose of C3plants. Functional Plant Biology, 2004, 31(9): 857- 877.

[41] Werner C, Schnyder H, Cuntz M, Keitel C, Zeeman M J, Dawson T E, Badeck F W, Brugnoli E, Ghashghaie J, Grams T E E, Kayler Z E, Lakatos M, Lee X, Máguas C, Ogée J, Rascher K G, Siegwolf R T W, Unger S, Welker J, Wingate L, Gessler A. Progress and challenges in using stable isotopes to trace plant carbon and water relations across scales. Biogeosciences, 2012, 9(8): 3083- 3111.

[42] Gleixner G, Scrimgeour C, Schmidt H L, Viola R. Stable isotope distribution in the major metabolites of source and sink organs ofSolanumtuberosumL.: a powerful tool in the study of metabolic partitioning in intact plants. Planta, 1998, 207(2): 241- 245.

[43] Gleixner G, Schmidt H L. Carbon isotope effects on the fructose- 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase reaction, origin for non-statistical13C distributions in carbohydrates. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1997, 272(9): 5382- 5387.

[44] Rossmann A, Butzenlechner M, Schmidt H L. Evidence for a nonstatistical carbon isotope distribution in natural glucose. Plant Physiology, 1991, 96(2): 609- 614.

[45] Hobbie E A, Werner R A. Intramolecular, compound-specific, and bulk carbon isotope patterns in C3and C4plants: a review and synthesis. New Phytologist, 2004, 161(2): 371- 385.

[46] Park R, Epstein S. Metabolic fractionation of C13& C12in plants. Plant Physiology, 1961, 36(2): 133- 138.

[47] Duranceau M, Ghashghaie J, Badeck F, Deleens E, Cornic G.δ13C of CO2respired in the dark in relation toδ13C of leaf carbohydrates inPhaseolusvulgarisL. under progressive drought. Plant, Cell & Environment, 1999, 22(5): 515- 523.

[48] Ghashghaie J, Duranceau M, Badeck F W, Cornic G, Adeline M T, Deleens E.δ13C of CO2respired in the dark in relation toδ13C of leaf metabolites: comparison betweenNicotianasylvestrisandHelianthusannuusunder drought. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2001, 24(5): 505- 515.

[49] Tcherkez G, Nogués S, Bleton J, Cornic G, Badeck F, Ghashghaie J. Metabolic origin of carbon isotope composition of leaf dark-respired CO2in French bean. Plant Physiology, 2003, 131(1): 237- 244.

[50] Klumpp K, Schäufele R, Lötscher M, Lattanzi F A, Feneis W, Schnyder H. C-isotope composition of CO2respired by shoots and roots: fractionation during dark respiration? Plant, Cell & Environment, 2005, 28(2): 241- 250.

[51] Hibberd J M, Quick W P. Characteristics of C4photosynthesis in stems and petioles of C3flowering plants. Nature, 2002, 415(6870): 451- 454.

[52] Berveiller D, Damesin C. Carbon assimilation by tree stems: potential involvement of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase. Trees, 2008, 22(2): 149- 157.

[53] Badeck F W, Tcherkez G, Nogués S, Piel C, Ghashghaie J. Post-photosynthetic fractionation of stable carbon isotopes between plant organs-a widespread phenomenon. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 2005, 19(11): 1381- 1391.

[54] Atkin O K, Evans J R, Ball M C, Siebke K, Pons T L, Lambers H. Light inhibition of leaf respiration: the role of irradiance and temperature//Moller I M, Gardestrom P, Gliminius K, Glaser E, eds. Plant Mitochondria: from Gene to Function. Leiden: Backhuys Publishers, 1998: 567- 574.

[55] Barbour M M, McDowell N G, Tcherkez G, Bickford C P, Hanson D T. A new measurement technique reveals rapid post-illumination changes in the carbon isotope composition of leaf-respired CO2. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2007, 30(4): 469- 482.

[56] Werner C, Hasenbein N, Maia R, Beyschlag W, Máguas C. Evaluating high time-resolved changes in carbon isotope ratio of respired CO2by a rapid in-tube incubation technique. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 2007, 21(8): 1352- 1360.

[57] Reddy M M, Vani T, Raghavendra A S. Light-enhanced dark respiration in mesophyll protoplasts from leaves of pea. Plant Physiology, 1991, 96(4): 1368- 1371.

[58] Xue X, Gauthier D A, Turpin D H, Weger H G. Interactions between photosynthesis and respiration in the green algaChlamydomonasreinhardtii(characterization of light-enhanced dark respiration). Plant Physiology, 1996, 112(3): 1005- 1014.

[59] Atkin O K, Evans J R, Siebke K. Relationship between the inhibition of leaf respiration by light and enhancement of leaf dark respiration following light treatment. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology, 1998, 25(4): 437- 443.

[60] Tcherkez G, Farquhar G D. Carbon isotope effect predictions for enzymes involved in the primary carbon metabolism of plant leaves. Functional Plant Biology, 2005, 32(4): 277- 291.

[61] Nunes-Nesi A, Sweetlove L J, Fernie A R. Operation and function of the tricarboxylic acid cycle in the illuminated leaf. Physiologia Plantarum, 2007, 129(1): 45- 56.

[62] Tcherkez G, Mahé A, Gauthier P, Mauve C, Gout E, Bligny R, Cornic G, Hodges M. In folio respiratory fluxomics revealed by13C isotopic labeling and H/D isotope effects highlight the noncyclic nature of the tricarboxylic acid “cycle” in illuminated leaves. Plant Physiology, 2009, 151(2): 620- 630.

[63] Sweetlove L J, Beard K F M, Nunes-Nesi A, Fernie A R, Ratcliffe R G. Not just a circle: flux modes in the plant TCA cycle. Trends in Plant Science, 2010, 15(8): 462- 470.

[64] Barbour M M, Hunt J E, Kodama N, Laubach J, McSeveny T M, Rogers G N D, Tcherkez G, Wingate L. Rapid changes inδ13C of ecosystem-respired CO2after sunset are consistent with transient13C enrichment of leaf respired CO2. New Phytologist, 2011, 190(4): 990- 1002.

[65] DeNiro M J, Epstein S. Mechanism of carbon isotope fractionation associated with lipid synthesis. Science, 1977, 197(4300): 261- 263.

[66] Schnyder H, Lattanzi F A. Partitioning respiration of C3-C4 mixed communities using the natural abundance13C approach-testing assumptions in a controlled environment. Plant Biology, 2005, 7(6): 592- 600.

[67] Brugnoli E, Farquhar G D. Photosynthetic fractionation of carbon isotopes//Leegood R C, Sharkey T D, von Caemmerer S, eds. Photosynthesis: Physiology and Metabolism. Berlin: Springer, 2000: 399- 434.

[68] Oren R, Sperry J S, Katul G G, Pataki D E, Ewers B E, Phillips N, Schäfer K V R. Survey and synthesis of intra-and interspecific variation in stomatal sensitivity to vapour pressure deficit. Plant, Cell & Environment, 1999, 22(12): 1515- 1526.

[69] Valladares F, Pearcy R W. Interactions between water stress, sun-shade acclimation, heat tolerance and photoinhibition in the sclerophyllHeteromelesarbutifolia. Plant, Cell & Environment, 1997, 20(1): 25- 36.

[70] Sun W, Resco V, Williams D G. Environmental and physiological controls on the carbon isotope composition of CO2respired by leaves and roots of a C3woody legume (Prosopisvelutina) and a C4perennial grass (Sporoboluswrightii). Plant, Cell & Environment, 2012, 35(3): 567- 577.

[71] Sun W, Resco V, Williams D G. Nocturnal and seasonal patterns of carbon isotope composition of leaf dark-respired carbon dioxide differ among dominant species in a semiarid savanna. Oecologia, 2010, 164(2): 297- 310.