Prevalence of risk factors for noncommunicable diseases among rural women in Yemen

2018-06-06GawadAlwabr

Gawad M.A. Alwabr

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized the right of every human to live a healthy life [ 1]. However, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and associated risk factors have emerged rapidly and have become a major challenge to public health around the world [ 2].

Today, NCDs are responsible for more than 75.0% of deaths worldwide [ 3]. NCDs,mainly cardiovascular diseases, were reported to be responsible for 64.0% of global deaths in 2014 [ 4]. They are responsible for more than 80.0% of cardiovascular and diabetes deaths and nearly 90.0% of deaths from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that occur in low- and middle-income countries[ 5]. About 38 million people die every year because of NCDs[ 6]. Diabetes mellitus is directly responsible for 3.5% of NCD deaths [ 7]. About 18.0% of global deaths are due to high blood pressure [ 6].

The increasing prevalence of behavioral and anthropological risk factors for these lifestyle diseases is expected to be a cause of the alarming increase in NCDs [ 8]. The main risk factors for NCDs include high blood pressure, tobacco use, harmful alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, high cholesterol level, high blood glucose level, overweight/obesity, and low consumption of fruits/vegetables, accounting for about 80.0%of deaths caused by heart disease and stroke [ 9]. More individuals, populations, and communities are adopting unhealthy lifestyles, which promote the development of NCDs [ 10].Additionally, with more than half of the global population in urban areas, risk factors associated with urbanization such as diet, obesity, hypertension, and a decrease in physical activity will all have significant impacts on the health of the population [ 11]. The prevalence of obesity and that of overweight are gradually increasing in developing countries as people experience changes in diet and physical activity patterns because of the in fluence of Western culture [ 12].

Nutrition-related NCDs are the most frequent cause of morbidity and death in most countries in the eastern Mediterranean region, particularly cardiovascular disease,diabetes, and cancer [ 13]. Food patterns represent a broader picture of food and nutrient consumption and may therefore be more predictive of disease risk than individual or nutrient feedings [ 14]. As a correct dose of medicine is essential for treating an illness, similarly there is an equally important role of a healthy diet and physical exercise for promotion of good health [ 15].

Too few studies on NCD risk factors have been conducted in Yemen. The aim of this study was to expand the evidence based on the prevalence of risk factors for the main NCDs(such as diabetes mellitus, blood pressure, and obesity) among rural women in Yemen.

Methods

Study design and sampling

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted among 450 rural women in the age range from 18 to 60 years who presented in the targeted health centers of Sana’ a and Al-Mahweet governorates during the time of the study. Nonprobability convenient sampling was used to select the participants.

Data collection

Data were collected by a structured questionnaire developed in accordance with the WHO STEPS guidelines, consisting of social and demographic characteristics, healthy lifestyle,and behavioral risk factors related to NCDs such as physical activity, diet style, tobacco consumption, and qat consumption, as step 1. The questionnaire was modified to suit local needs. Physical measurements of height and weight were specified to calculate the body mass index (BMI). As well as measuring of blood pressure was done in step 2 (waist circumference excluded), and step 3 consisted of biochemical measurements of fasting blood glucose (total cholesterol levels excluded).

Physical measurements of height and weight for calculation of BMI and blood pressure were obtained. Measurement of height in centimeters was recorded with the participant in the standing position by use of a standardized stature meter,and weight in kilograms (barefooted) was recorded with standardized electronic weighing equipment. BMI is a person’ s weight in kilograms (kg) divided by the person’ s height in square meters, and expressed globally in the unit of kilograms per square meter (kg/m2). Obesity was defined as BMI≥ 30 kg/m2[ 16]. Blood pressure in millimeters of mercury(mm Hg) was recorded with standardized electronic blood pressure monitoring equipment. The average of two readings taken at 5-minute intervals was used for the final value. Blood pressure was classified as normal, hypotension, or hypertension: generally, hypotension corresponds to systolic blood pressure lower than 90 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure lower than 60 mm Hg, hypertension corresponds to systolic blood pressure of at least 140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure of at least 90 mm Hg, and normal corresponds to blood pressure within the range from systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure of 80 mm Hg to systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg [ 17].

For collection of participants’ blood samples for fasting blood glucose analysis as a biochemical measurement, participants were asked to fast overnight and not consume any food after dinner until they gave blood samples in the health center on the morning of the following day. Fasting blood glucose was measured with an automated chemistry analyzer by a photometric method. Diagnosis of diabetes was based on the international criterion recommended by WHO: fasting blood glucose concentration of 126 mg/dL or greater [ 18]. The questionnaire was completed by the researcher while measuring blood pressure and taking anthropometric measurements and while blood samples were being collected by the nurses in the health centers. Ethics approval was obtained from the Ministry of Public Health and Population, Yemen. To ensure the feasibility and applicability of the study tool, a pilot study was conducted on a random sample of 30 women, which enabled modification of the questionnaire as well as the field interview procedures. Those who participated in the pilot study were excluded from the study.

The objective of the study was explained to the participants.Verbal consent was obtained from all women before their participation in the study. Data were collected from September to November 2016. The exclusion criteria included pregnant women, women who were younger than 18 years, and women who were older than 60 years.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 was used for data analysis.The descriptive statistics, including frequency distributions and percentages, were calculated. Means and standard deviations were used. A chi-square test was used to determine the relationship between variables. P < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

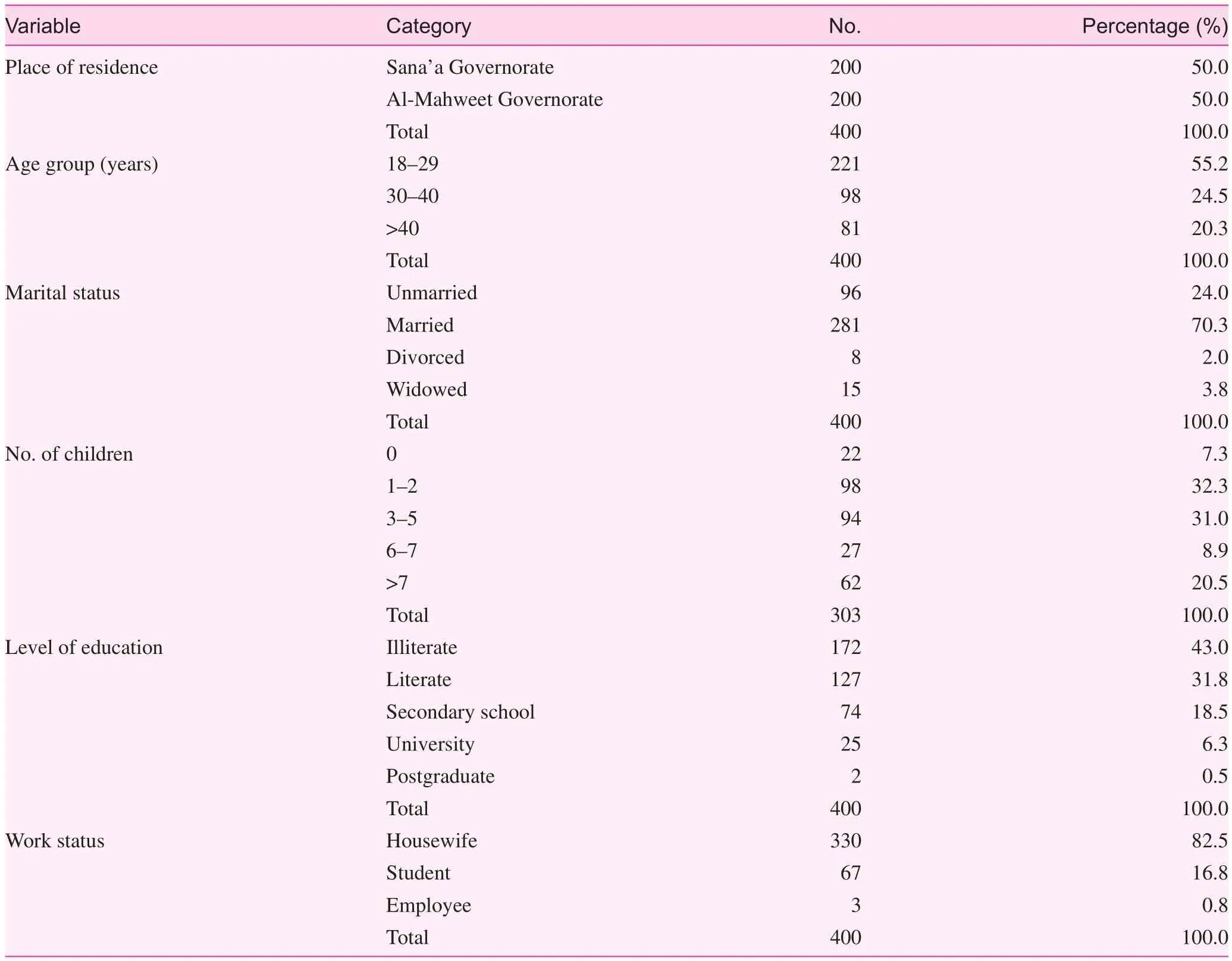

The total number of female participants for the study was 450:225 (50.0%) were from the rural areas of Sana’ a Governorate,and the other 225 (50.0%) were from the rural areas of Al-Mahweet Governorate. The response rate was 89.0% (400).All the study participants were in the age range from 18 to 60 years. Most of the respondents (221, 55.2%) were in the age group from 18 to 29 years. Most of the respondents were married (281, 70.3%). Ninety-eight (32.3%) of the married women had one or two children, 94 (31.0%) had three to five children, and 62 (20.5%) had more than seven children. One hundred seventy-two respondents were illiterate (43.0%), and 330 (82.5%) were housewives ( Table 1).

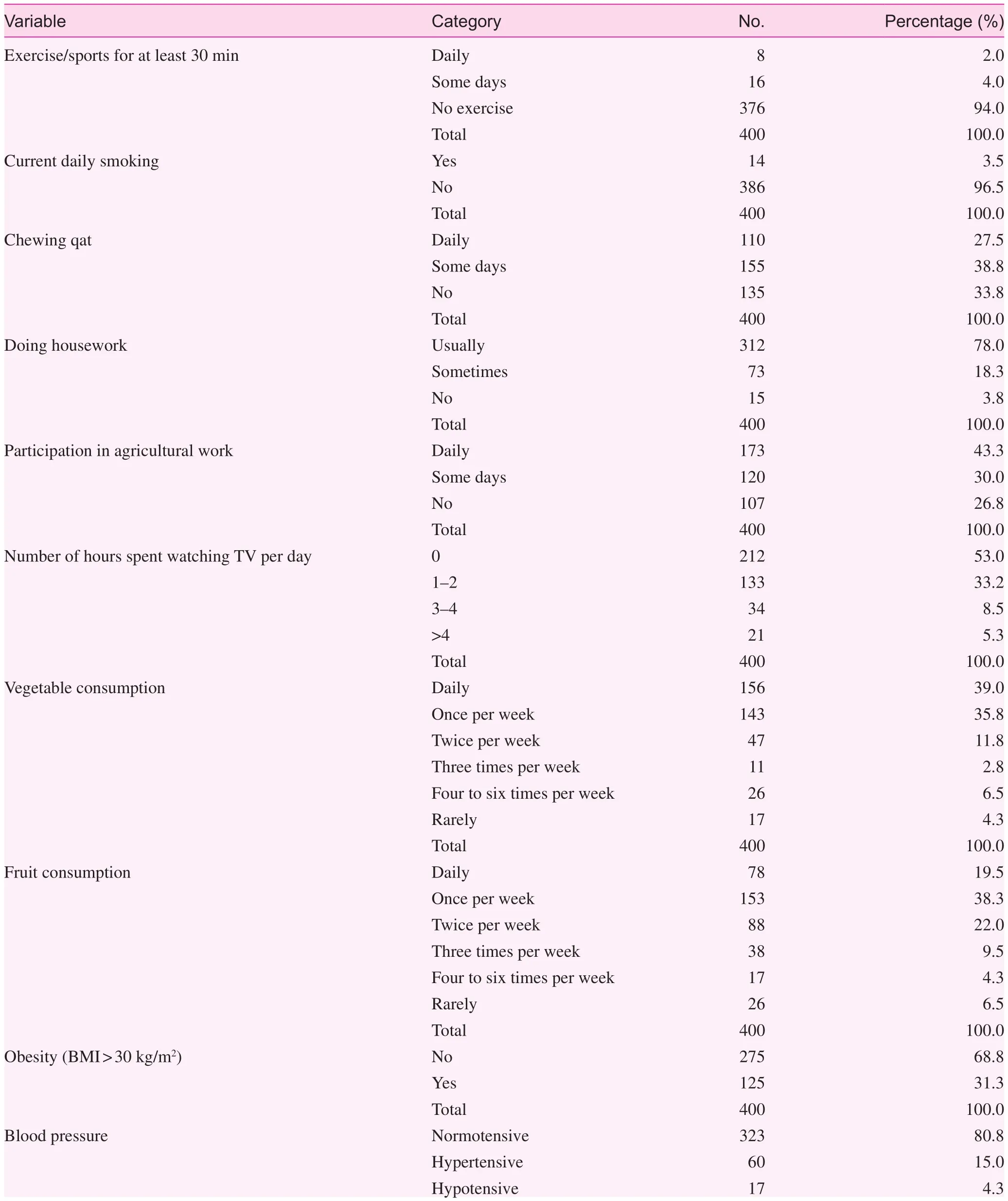

Table 2 shows that 94.0% of the respondents were physically inactive, 3.5% were smokers, and 66.3% were qat chewers, with 27.5% of them chewing qat daily and 38.8%chewing qat on some days. Most respondents (78.0%) usually did housework, and 43.3% of them participated daily in agricultural work. In addition, 47.0% of respondents watched TV:33.2% of them spent 1– 2 hours per day watching TV, 8.5%spent 3– 4 hours per day watching TV, and 5.3% spent more than 4 hours per day watching TV. Only 39.0% of respondents ate vegetables daily, while 19.5% consumed fruits daily.

Among the respondents, 31.3% were obese(BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), 15.0% were hypertensive, 4.3% were hypotensive, and 80.8% were normotensive. Further, 7.8% of respondents had diabetes mellitus (fasting blood glucose level greater than 125 mg/dL).

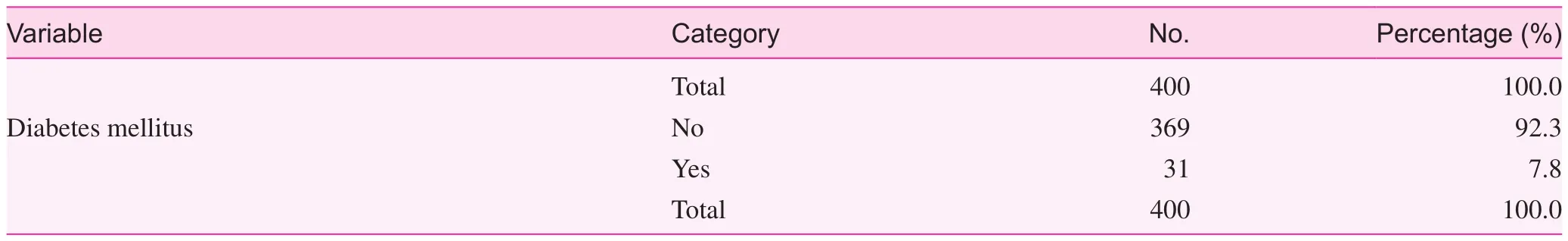

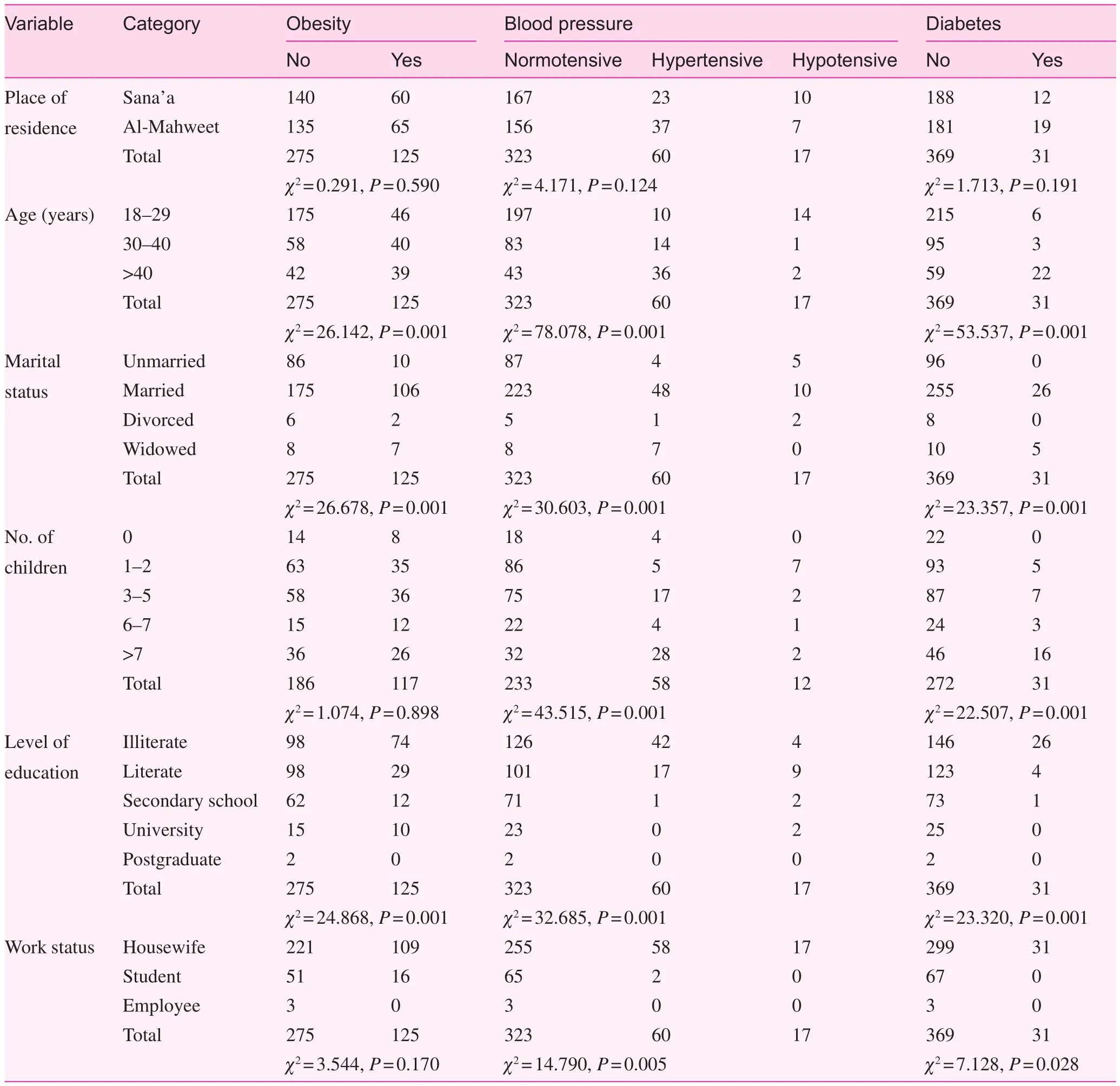

Table 3 shows the association between sociodemographic variables and obesity, blood pressure, and diabetes mellitus.The place of residence was insignificantly associated with obesity, diabetes mellitus, and blood pressure ( P > 0.05).The age group was significantly associated with obesity( P = 0.001), blood pressure ( P = 0.001), and diabetes mellitus( P = 0.001). Marital status was significantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.001), blood pressure ( P = 0.001), and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.001). The number of children was significantly associated with blood pressure ( P = 0.001) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.001), while it was insignificantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.898). The level of education was significantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.001), blood pressure ( P = 0.001),and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.001). Work status was signifi-cantly associated with blood pressure ( P = 0.005) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.028), while it was insignificantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.170).

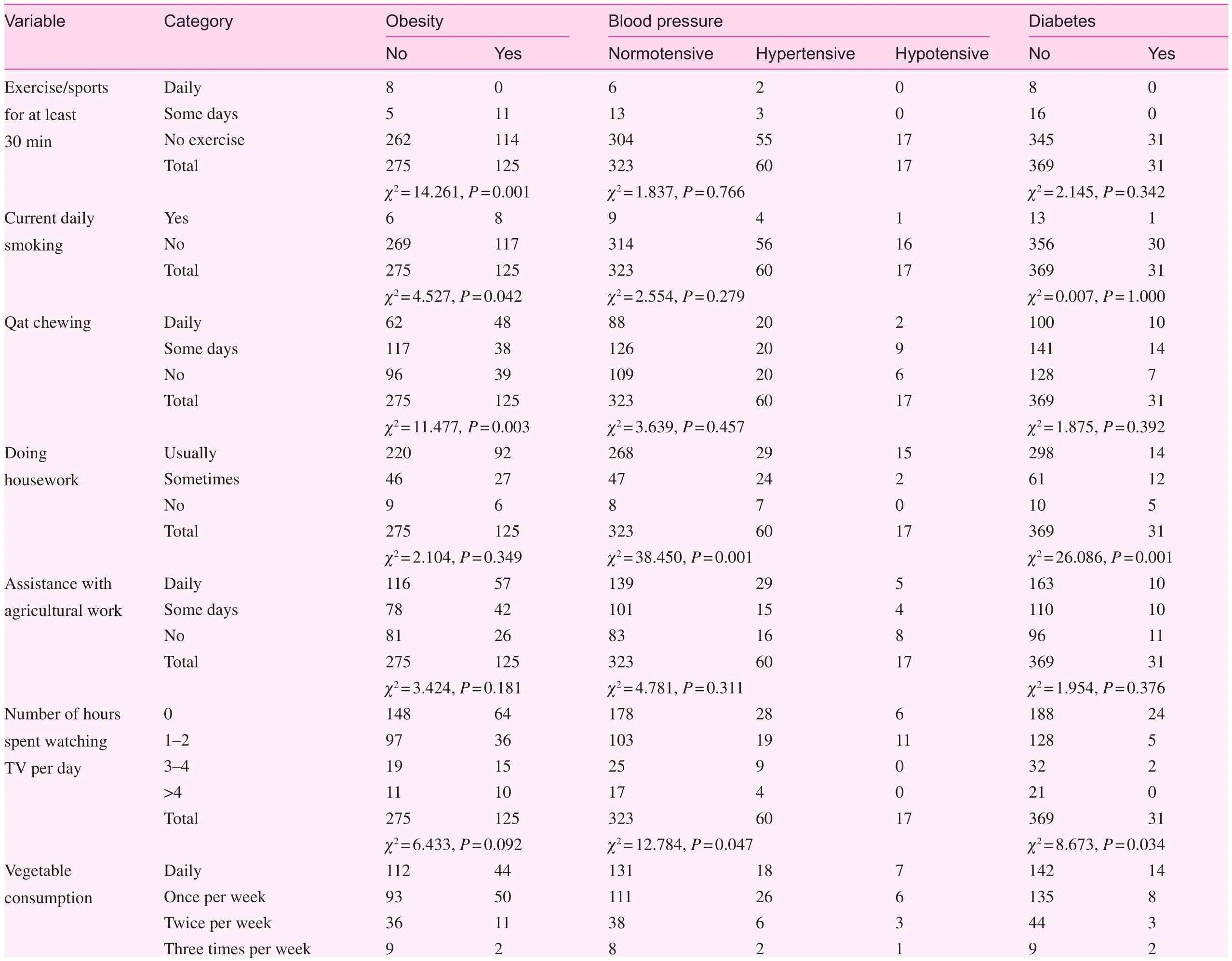

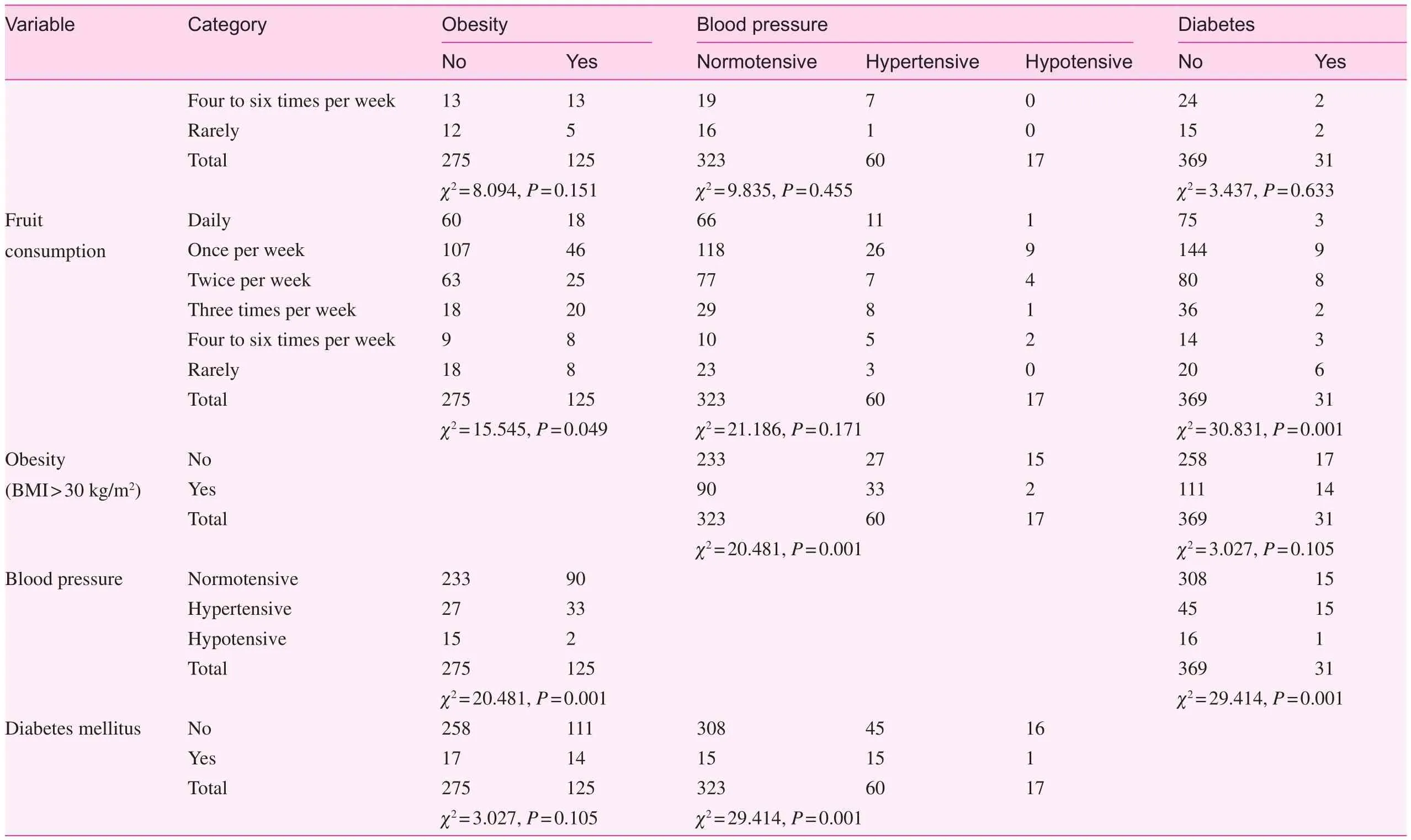

Table 4 shows the association between common risk factors and obesity, blood pressure, and diabetes mellitus. Physical activity was insignificantly associated with blood pressure( P = 0.766) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.342), while it was significantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.001). Smoking was significantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.042), while it was insignificantly associated with blood pressure ( P = 0.279) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 1.000). Qat chewing was significantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.003), while it was insignifi-cantly associated with blood pressure ( P = 0.457) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.391).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents ( n = 400)

Doing housework was insignificantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.349), while it was significantly associated with blood pressure ( P = 0.001) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.001).Participation in agricultural work was insignificantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.181), blood pressure ( P = 0.311),and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.376). The number of hours spent watching TV per day was insignificantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.092), while it was significantly associated with blood pressure ( P = 0.047) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.037).Consuming vegetables was insignificantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.151), blood pressure, ( P = 0.455) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.633), and eating fruits was significantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.049) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.001).There were significant associations between obesity and blood pressure ( P = 0.001), as well as between blood pressure and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.001).

Table 2. Distribution of noncommunicable disease risk factors among the respondents ( n = 400)

Table 2 (continued)

Discussion

Maternal health, malnutrition, and communicable diseases are the main concerns in Yemen. This study presented the NCD risk factor burden among rural women of Sana’ a and Al-Mahweet governorates, using the WHO STEPS tool.According to our findings, most of the respondents (55.2%)were in age group from 18 to 29 years, 70.3% were married,43.0% were illiterate, and 82.5% were housewives.

Most respondents (94.0%) did not exercise regularly.Physical inactivity is considered an independent risk factor for a number of chronic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension [ 19]. The high level of physical inactivity observed in this study could be attributed to the limited opportunities of Yemeni females to engage in physical activity because of the absence of physical education programs for girls, in addition to cultural reasons where families may not encourage females to engage in physical activity, and also because of the lack of sports centers in rural areas particularly for women. This finding is in agreement with a previous study conducted in India that indicated that 95.0% of the study population was physically inactive [ 20]. However, it is incompatible with the results obtained in other studies. A study conducted in Saudi Arabia among female university students indicated that 61.7% were physically inactive [ 19]; a study conducted in India revealed that 22.0% of women were physically inactive [ 21]; and a study conducted in Sri Lanka indicated that 31.0% were physically inactive [ 22]. Participation in regular physical activity over time is associated with a decrease in all causes of death [ 23].

In the present study, the percentage of smokers was low(3.5%), which might be attributed to the conservative community as in Yemen, where women may feel ashamed to admit certain habits, such as smoking, in addition to cultural unacceptability and less freedom to smoke among women.This finding is in agreement with findings in previous studies.A study conducted in Saudi Arabia among female university students indicated that 3.1% were current smokers [ 19], and a study conducted in Afghanistan indicated that the overall prevalence of smoking was 0.3% among women [ 24]. However, it is incompatible with the results obtained in other studies. A study conducted in India indicated that 40.0% of women were current smokers [ 21], and another study conducted in India indicated that 19.16% of womens were smokers [ 20].

This study showed that 27.5% of women chewed qat daily and 38.8% chewed qat on some days. On the basis of these findings, the prevalence of qat chewing is high, which might be attributed to cultural acceptability.

In the current study, 78.0% of women usually did housework and 43.3% assisted their family daily in agricultural work. Doing housework and agricultural work are the two important segments of daily life in which most time is usually spent; as a proxy for physical activity, they are protective factors against obesity as well as other NCDs.

In the present study, 53.0% of respondents did not watch TV. The low level of women who watched TV might be attributed to unavailability of electricity because of the current political and economic situation in Yemen. This finding is incompatible with the results obtained in a previous study conducted in Saudi Arabia that indicated that 91.2% of womens spent more than 2 hours per day watching TV [ 25].

The present study showed that 39.0% of respondents ate vegetables daily, while only 19.5% consumed fruits daily. The inadequate and low consumption of fruits and vegetables by most respondents might be attributed to economic problems.According to the WHO recommendation, an adult should consume at least two to three servings per day as part of ahealthy dietary requirement [ 20, 26]. This finding is in agreement with findings in previous studies. A study conducted in India found low fruit consumption in both sexes [ 20]; a study conducted in Saudi Arabia among female university students indicated that 70.0% of them consumed fruits one to five times per week and 59.9% consumed vegetables one to five times per week [ 19]; and a study conducted in Afghanistan revealed that 41.1% of participants consumed vegetables more than three times per week and 42.5% consumed fruits more than three times per week [ 24].

Table 3. Association of sociodemographic variables with obesity, blood pressure, and diabetes mellitus ( n = 400)

In this study, 31.3% of respondents were obese. The low prevalence of obesity among respondents might be because

most of them do housework and agricultural work daily, which are protective factors against obesity, as well as other NCDs.This finding is in agreement with findings in previous studies. A study conducted in Sri Lanka indicated that 38.7% of women were obese [ 22]; a study conducted in Afghanistan indicated that the prevalence of obesity was 37.3% in women[ 24]; a study conducted in India indicated that 34.0% of womens were obese [ 27]; and another study conducted in India indicated that the 33.0% of womens were obese [ 21]. However,the finding is incompatible with results obtained in other studies. A study conducted in Palestine indicated that the overall prevalence of obesity among female students was 9.17% [ 28];a study conducted in Saudi Arabia among female university students indicated that the prevalence of obesity was 18.1%[ 19]; and a study conducted in Brazil indicated that the obesity rate was 14.0% [ 28].

Table 4. Association between common risk factors and obesity, blood pressure, and diabetes mellitus ( n = 400)

Table 4 (continued)

According to the findings of this study, 15.0% of the respondents have hypertension. This finding is incompatible with the results obtained in previous studies, with the rate being lower than that in previous studies. A study conducted in Afghanistan indicated that the prevalence of hypertension was 46.5% in women [ 24]; a study conducted in Brazil indicated that arterial hypertension was present in 22.4% of female participants [ 28]; and a study conducted in India indicated that high blood pressure was observed in nearly 30.0%of womens [ 27].

This study also showed that only 7.8% of women have diabetes mellitus. This finding is in agreement with findings in previous studies. A study conducted in Sri Lanka indicated that 4.8% of womens had diabetes [ 22]; a study conducted in Afghanistan indicated that the prevalence of diabetes was 12.0% in women [ 24]; and a study conducted in Brazil indicated that 3.7% of womens had diabetes [ 28].

The low prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus in the present study might be because most of the female participants (79.7%) were younger than 40 years, and there are fewer risk factors for hypertension and diabetes mellitus in this age range.

In the present study, age was significantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.001), blood pressure ( P = 0.001), and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.001). Respondents older than 40 years were more likely to have high blood pressure as compared with respondents in the other age groups. This finding is in agreement with findings in previous studies. A study conducted in Afghanistan indicated that age was a significant risk factor for obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, and also indicated high prevalence of diabetes in older age groups who also have other aging diseases [ 24]; a study conducted in Brazil indicated there was correlation between hypertension and age greater than 60 years [ 28]; and a study conducted in India indicated that the prevalence of all NCD risk factors increased with age [ 27].

This study showed that the marital status of the respondents was significantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.001),blood pressure ( P = 0.014), and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.001).The rates of obesity and diabetes were more likely to be high in widowed respondents, while blood pressure was more likely to be high in divorced respondents.

In the present study, the number of children the respondents had was significantly associated with blood pressure( P = 0.002) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.001), while it was insignificantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.900).

In this study, the level of education was significantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.001), blood pressure ( P = 0.020),and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.001). In addition, the work status of respondents was significantly associated with blood pressure ( P = 0.001) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.028), while it was insignificantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.171).

This study showed that there were insignificant associations between physical inactivity and blood pressure ( P = 0.766) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.342), while physical inactivity was significantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.001). Smoking was significantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.042), while it was insignificantly associated with blood pressure ( P = 0.279) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 1.000). In addition, qat chewing was significantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.003), while it was insignificantly associated with blood pressure ( P = 0.457) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.391). These findings are incompatible with the results obtained in a previous study conducted in India that indicated that physical inactivity and smoking were associated with the prevalence of obesity and hypertension, but were not related to the prevalence of diabetes [ 27].However, they are in agreement with the findings in a previous study conducted in Yemen that indicated that there was a positive correlation between BMI and the frequency of qat chewing, and that there was no correlation between qat chewing and blood pressure [29].

This study showed that participation of women in housework was insignificantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.349),while it was significantly associated with blood pressure( P = 0.001) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.001). However, participation of women in agricultural work was insignificantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.181), blood pressure ( P = 0.311),and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.376).

In the present study, the number of hours spent watching TV per day was insignificantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.092),while it was significantly associated with blood pressure( P = 0.047) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.037). Consuming vegetables was insignificantly associated with obesity ( P = 0.151),blood pressure ( P = 0.455), and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.633),while eating fruits was significantly associated with obesity( P = 0.049) and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.001).

There were significant associations between obesity and blood pressure ( P = 0.001), as well as between blood pressure and diabetes mellitus ( P = 0.001), showing that the factors are related to each other. These findings are in agreement with findings in previous studies. A study conducted in Afghanistan indicated an independent significant association of obesity and blood pressure as well as diabetes [ 24]. A study conducted in Brazil indicated that obesity and diabetes were associated with arterial hypertension [ 28].

Conclusions

The study findings showed poor practice of healthy lifestyles such as physical activities and consumption of vegetables and fruits. Participation of women in housework as well as in agricultural work as physical activities is of prime importance for lowering the levels of obesity, blood pressure, and diabetes. Frequent campaigns and educational programs are to be encouraged for the adoption of healthy lifestyle practices and health promotion. They should improve awareness of the ill effects of qat chewing among the masses, especially the high-risk groups. In view of that, the present study was conducted in rural areas and the study participants may not be representative of the general population. Thus more comprehensive studies should be extended to women from urban and rural areas.

Acknowledgments

I thank the fieldwork team and health centers in the study areas(Saleh H.M. Ali, Khaled A. Maeed, Hemeir H. Al-roab, Maha A. Borge, Esam M. Alatar, and Adel Y. Abdollah) for their contribution in conducting the fieldwork. I thank Sultan Haza’ a Saif Qassim for revision of the English language of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-pro fit sectors.

1. Wesonga R, Guwatudde D, Bahendeka SK, Mutungi G, Nabugoomu F, Muwonge J. Burden of cumulative risk factors associated with non-communicable diseases among adults in Uganda:evidence from a national baseline survey. Int J Equity Health 2016;15:195.

2. Essa HAEE, El-Shemy MBA. Prevalence of lifestyle-associated risk factors for non-communicable diseases and its effect on quality of life among nursing students, faculty of nursing, Tanta University. Int J Adv Res 2015;3(5):429– 46.

3. AL-Daboony SJ. Knowledge, attitude, and practices towards non-communicable disease risk factors among medical staff.Global J Med Res 2016;16(3):4–19.

4. Alzeidan R, Rabiee F, Mandil A, Hersi A, Fayed A. Non-communicable disease risk factors among employees and their families of a Saudi University: an epidemiological study. PLoS One 2016,11(11):e0165036.

5. Srivastava A, Sharma M, Gupta S, Saxena S. Epidemiological investigation of lifestyle associated modifiable risk factors among medical students. Natl J Med Res 2013;3(3):210– 5.

6. Naseem S, Khattak UK, Ghazanfar H, Irfan A. Prevalence of non-communicable diseases and their risk factors at a semi-urban community, Pakistan. Pan Afr Med J 2016,23:151.

7. Kumar P, Singh CM, Agarwal N, Pandey S, Ranjan A, Singh GK. Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable disease in a rural area of Patna, Bihar – a WHO step wise approach. Indian J Prev Soc Med 2013;44(1– 2):46– 53.

8. Oommen AM, Abraham VJ, George K, Jose VJ. Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in rural & urban Tamil Nadu. Indian J Med Res 2016;144:460– 71.

9. Kufe NC, Ngufor G, Mbeh G, Mbanya JC. Distribution and patterning of non-communicable disease risk factors in indigenous Mbororo and nonautochthonous populations in Cameroon: crosssectional study. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1188.

10. Mwai D, Muriithi M. Non-communicable diseases risk factors and their cobtribution to NCD incidences in Kenya. Eur Sci J 2015;11(30):268– 81.

11. Wu F, Guo Y, Chatterji S, Zheng Y, Naidoo N, Jiang Y, et al.Common risk factors for chronic non-communicable diseases among older adults in China, Ghana, Mexico, India, Russia and South Africa: the study on global Ageing and adult health(SAGE) wave 1. BMC Public Health 2015;15:88.

12. Gbary AR, Kpozehouen A, Houehanou YC, Djrolo F, Amoussou MPG, Tchabi Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of overweight and obesity: findings from a cross-sectional community-based survey in Benin. Global Epidemic Obesity 2014;2:3.

13. Musaiger AO, Al-Hazzaa HM. Prevalence and risk factors associated with nutrition-related non-communicable diseases in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Int J Gen Med 2012;5:199– 217.

14. Wang H, Deng F, Qu M, Yang P, Yang B. Association between dietary patterns and chronic diseases among Chinese adults in Baoji. Int J Chron Dis 2014;2014:548269.

15. Adhikari K, Adak MR. Behavioural risk factors of non-communicable diseases among adolescents. J Inst Med 2012;34(3):39– 43.

16. Al-Shehri FS, Moqbel MM, Al-Shahrani AM, Al-Khaldi YM,Abu-Melha WS. Management of obesity: Saudi clinical guideline. Saudi J Obesity 2013;1(1):18– 30.

17. Passos VMA, Barreto SM, Diniz LM, Lima-Costa MF. Type 2 diabetes: prevalence and associated factors in a Brazilian community – the Bambu í health and aging study. São Paulo. Med J 2005;123:66– 71.

18. Lopes ACS, Santos LCd, Lima-Costa MF, Caiaffa WT. Nutritional factors associated with chronic non-communicable diseases – the Bambu í project: a population-based study. Cad. Saúde Pública, Rio De Janeiro 2011;27(6):1185– 91.

19. Desouky DS, Omar MS, Nemenqani DM, Jabbar J, Tarak-Khan NM. Risk factors of non-communicable diseases among female university students of the health colleges of Taif University. Int J Med Med Sci 2014;6(3):97– 107.

20. Krishna R, Dijo D, Krishnaveni K, Sambathkumar R. Noncommunicable diseases: prevalence and risk factors among adults in rural community. Int J Chemtech Res 2017;10(5):197– 202.

21. Sugathan TN, Soman CR, Sankaranarayanan K. Behavioural risk factors for non-communicable diseases among adults in Kerala,India. Indian J Med Res 2008;127:555– 63.

22. Swarnamali AKSH, Jayasinghe MVTN, Katulanda P. Identifi-cation of risk factors for selected non-communicable diseases among public sector of fice employees, Sri Lanka. Int J Health Life-Sci 2015;1(2):12– 24.

23. Lollgen H, Bockenhoff A, Knapp G. Physical activity and allcause mortality: an updated meta-analysis with different intensity categories. Int J Sports Med 2009;30:213– 24.

24. Saeed KMI. Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in the adult population of urban areas in Kabul City,Afghanistan. Cen Asian J Global Health 2013;2(2):549–69.

25. Al-Hazzaa HM. Prevalence of physical inactivity in Saudi Arabia: a brief review. East Mediter Health J 2004;10(4/5):663– 70.

26. Chakma JK, Gupta S. Lifestyle practice and associated risk factors of non-communicable diseases. Int J Health Allied Sci 2017;6(1):20– 5.

27. Thankappan KR, Shah B, Mathur P, Sarma PS, Srinivas G, Mini GK, et al. Risk factor pro file for chronic non-communicable diseases: results of a community-based study in Kerala, India.Indian J Med Res 2010;131:53– 63.

28. Ghrayeb FAW, Rusli M, Al Rifai A, Ismail M. Prevalence of lifestyle-related risk factors contributing for non-communicable diseases among adolescents in Tarqumia, Palestine. Int Med J 2014;21(3):1– 5.

29. Laswar AN, Darwish H. Prevalence of cigarette smoking and Khat chewing among Aden University medical students and their relationship to BP and body mass index. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2009;20(5):862–66.

杂志排行

Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- The role of the teaching practice in undergraduate education– A British perspective

- Geographic and health system correlates of interprofessional oral health practice

- Genetic screening for quality-of-life improvement and post– genetic testing consideration in Saudi Arabia

- Cross-sectional analysis of obesity and high blood pressure among undergraduate students of a university medical college in South India

- Has Mayaro virus always existed or is it new ?

- Impacts from the implementation of a Novel Clinical Pharmacist Training Program in Changsha, Hunan Province, China