欧亚大陆高山林线温度的差异性分析

2018-03-08朱连奇张百平姚永慧曹艳萍

赵 芳,朱连奇,张百平,韩 芳,姚永慧,曹艳萍

1 河南大学 环境与规划学院, 开封 475004 2 中国科学院地理科学与资源研究所 资源与环境信息系统国家重点实验室, 北京 100101 3 江苏省地理信息资源开发与利用协同创新中心, 南京 210023 4 山东理工大学建筑工程学院, 淄博 255000

高山林线是山地森林带与高山带之间的过渡带,以上是树木稀少的高山冻原,以下是山地森林带。除了火灾、放牧、滑坡等因素对林线的破坏,自然林线的存在和分布主要受气候条件控制[1]。研究林线高度与气候指标的关系有助于探索林线存在的生理生态机理[2-3],预测林线对气候变化的响应[4-5],评估适合森林生长发育的环境[6]。

低温、强风、土壤贫瘠和干旱等不利的高山环境条件都可能限制树木生长或者生存,但是从宏观尺度来看,热量的缺乏(低温)是限制森林带向高山地区扩展的关键[1]。对全球不同地区林线温度进行比较发现,无论纬度位置和地势状况,林线位置具有相似的热量状况[7-9]。寻找与林线存在有关的等温线,包括最热月温度10 ℃[10-11],年生物温度3 ℃[12-13],温暖指数15 ℃·月[14-15],生长季平均温度6.4 ℃[8-9]等,以此预测林线位置的变化,探索林线形成的生理生态机理[16-17]成了林线研究的重要内容。林线等温线研究反映了低温对林线高度的控制,但是作为与时空尺度有关的生态过渡区,林线对温度变化的响应并非线性的,简单的线性相关在很大程度掩盖了林线生态气候的多样性和复杂性[18]。

实际上,受纬度位置、海陆分布、地势起伏、坡向等因素的影响,林线的气候特征具有明显的区域差异。热带湿润地区林线位置的气温年较差较小但日较差较大,而温带林线温度季变化显著,日变化较小[19-20]。这就意味着限制林线变化的因素也应具有区域差异性。研究发现,在厄瓜多尔北部的热带地区,影响树木幼苗的存活的关键是太阳辐射[21];芬兰北部大陆性气候区内,雪层覆盖维持了土壤湿度,减弱风蚀的影响,决定了林线分布[22];但在降水丰富的海洋性气候区内,春季和夏季长期的积雪通过缩短生长季限制了树木生长[23-24]。相应地,林线温度也呈现了多样性,例如尽管许多温带山体林线位置的最热月温度接近10 ℃[10],但是热带山地最热月温度可能低至5—6 ℃[25],位于高纬度的挪威最热月温度可能高达15.8 ℃[26]。

因此,除了研究与林线存在有关的等温线,探索不同地区林线温度指标的多样性,分析林线主导气候因子的区域差异也应受到人们的重视。但是先前研究或者受限于样本点过少,无法反映林线温度的区域差异,例如,对全球林线高度和温度关系进行的研究,Jobbagy和Jackson仅使用115个温带林线数据[27],Körner仅使用了青藏高原以外的46个林线数据[7-8],无法反映青藏高原林线的热量状况;或者研究本身侧重于林线存在的共同的等温线,选择性的忽略了林线温度和限制林线存在的温度指标的区域差异[8-15]。

欧亚大陆是世界上面积最大、环境最复杂的大陆,分布着世界上最多、变化最复杂的林线数据。这些数据分散在不同山地植被文献中,如何充分挖掘并利用这些数据,成为探索林线温度区域差异性的关键。本文在广泛收集林线高度数据的基础上,利用有效的温度资料,分析欧亚大陆及其不同生物气候区(主要是Köppen-Trewartha气候分类系统中的热带湿润气候区、亚热带湿润气候区、地中海气候区、温带大陆性和海洋性气候区、亚寒带相对海洋性和大陆性气候区和高原温带和亚寒带气候区)林线高度和林线温度的关系,确定不同区域影响林线高度的主导气候因子,以此展示林线温度和林线主导气候因子的多样性和复杂性。

1 数据和方法

1.1 数据来源及分布

本文中使用的林线高度数据,主要来源于各类已经公开发表的植被文献和山地垂直带文献。林线数据的甄别需要:1)依据定义:高山林线是介于山地森林带上限与树种线之间的过渡地带,即林线生态过渡带[18],其上限树木的高度不低于3m[7];2)文献中需明确指明林线以上树木高度低于3m,或该线以上为矮曲林带、高山灌丛带、高山草甸带或者高山灌丛草甸带;3)为消除山顶效应造成的假林线,林线和山顶的高差应大于200m[27];4)去掉受人为的影响如伐木、放牧等和一些局地的突发性的事故如雪崩、滑坡等影响而形成的假林线。林线高度的记录:1)通常依据文献中描述的山体的林线平均高度;2)如果明确指明为山地某一段或某一个坡向的林线,则分段、分坡向记录林线高度;3)如果没有直接给定林线高度,只是描述了林线生态过渡带的上下限高度,则记录其平均值为林线高度[28]。研究从文献中收集到欧亚大陆约410个林线数据,覆盖了几乎所有的高原和山脉。林线数据点的分布如图1所示。

图1 欧亚大陆410个林线数据点的分布Fig.1 Distribution of 410 timberline data sites in the Eurasian continent

林线通常位于较高海拔的山区,缺乏气象台站,无法直接获取林线温度。本文从一个高精度的全球月均温气候数据集WorldClim(1950—2000)提取林线温度。WorldClim基于全球范围24542个气象台站,通过薄板样条平滑样条算法进行站点数据的内插,并对插值结果进行严格的质量控制,数据精度高达30弧秒[29],近年来常用于分析山区不同物种垂直分布模式与气候的关系[30-32]、建立气候模型预测林线的潜在位置[9]等。由于WorldClim温度值代表了每个格网温度的平均值,为了尽量减小误差,使用双线性插值方法将林线周围的4个格网点的温度值内插至林线位置。

1.2 方法

研究统计了欧亚大陆林线位置这7个气候指标(MTWM、WI、ABT、CI、MTCM、ART、AMT)的最小值、最大值、平均值和标准差,根据先前研究常用的标准差最小的原则确定影响林线存在的主导气候因子[14-15]。对于WI和CI这些多月累计值,使用标准差与计算这些指标的月数(n)相除的结果,对于ABT需要乘以12除以n与其它指标的标准差进行比较[37]。

为了研究林线温度的多样性,本文依据常用的Köppen-Trewartha气候分类方案[38-39]和郑度的青藏高原气候区划方案[40]对欧亚大陆进行了气候区的划分,并分析了林线集中分布的热带湿润气候区、亚热带湿润气候区、地中海气候区、温带海洋性气候区、温带大陆性气候区、亚寒带相对海洋性气候区、亚寒带相对大陆性气候区、高原温带和高原亚寒带气候区与林线分布有关的气候指标(图2)。

图2 欧亚大陆不同气候区林线数据点的分布Fig.2 Distribution of timberline data sites in the different climate zones of the Eurasian continent

2 结果与分析

2.1 欧亚大陆林线气候指标的变化

从欧亚大陆林线位置气候指标的统计值(表1)可以看出,欧亚大陆林线变化最小(标准差小于2)的气候指标是ABT,WI和MTWM,其平均值分别为3.94 ℃、19.1 ℃·月、和11.27 ℃,其他指标都变化较大,其标准差均大于4。

表1欧亚大陆林线位置气候指标的最小值、最大值、平均值及标准差(N=410)

Table1Minimum,maximum,meanandstandarddeviationofclimaticvariablesattimberlinesintheEurasiancontinentbasedon410timberlinesites

统计项Statisticalitems气候指标ClimaticvariablesWI/(℃·月)CI/(℃·月)ABT/℃MTWM/℃MTCM/℃ART/℃AMT/℃最小值Minimum3.948.651.866.95-46.317.70-18.21最大值Maximum41.93286.937.2715.642.2155.907.27平均值Mean19.1077.963.9411.27-11.7323.000.09标准差Standarddevia-tion1.235.101.121.818.959.584.32

WI, warmth index, 温暖指数; CI, 寒冷指数, coldness index; AMT, annual biotemperature, 年生物温度; MTWM, mean temperature of the warmest month, 最热月温度; MTCM, mean temperature of the coldest month, 最冷月温度; ART, annual range of temperature, 气温年较差; AMT, annual mean temperature, 年均温

2.2 不同生物气候区林线温度差异性分析

2.2.1 热带湿润气候区

欧亚大陆热带林线主要分布在喜马拉雅山南侧热带湿润山地,向东连接川西滇北的亚热带山地,向西沿喜马拉雅南坡至不丹、锡金、尼泊尔和印度西部山地,林线高度为3600—4200m[41-42]。该地区林线位置标准差最小的3个气候指标是ABT,WI和AMT,平均值分别为4.63 ℃,21.72 ℃·月和3.56 ℃(表2),因此林线高度分布的限制因子为ABT: 4.63 ℃,WI: 21.72 ℃·月,AMT: 3.56 ℃。

表2 热带湿润气候区林线处气候指标的平均值和标准差Table 2 Mean and standard deviation of climatic variables at the tropical humid timberlines in the Eurasian continent

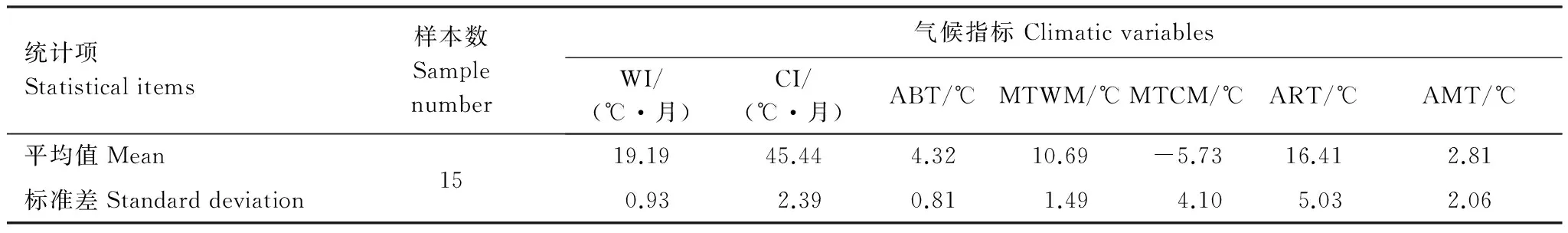

2.2.2 亚热带湿润气候区

亚热带地区林线主要分布在我国秦岭淮河以南地区和台湾地区以及日本的南部的亚热带湿润气候区。林线高度从日本kurobegorohdake的2450m[43]至滇西北横断山区的4150m[44]。根据表3,该气候区标准差最小的指标为ABT,WI和MTWM,平均值分别为4.32 ℃、19.19 ℃·月和10.69 ℃。

表3 亚热带湿润气候区林线处气候指标的平均值和标准差Table 3 Mean and standard deviation of climatic variables at the subtropical humid timberlines in the Eurasian continent

2.2.3 地中海气候区

地中海气候区林线主要分布在阿尔卑斯山南部山体、亚平宁北部和中部山地、巴尔干半岛,林线高度从亚平宁北部的和科西嘉岛的Monte Cinto的1750m升高至希腊Mt. Olympus的2300m[30]。如表4所示,该地区标准差最小的气候指标为ABT,WI及CI,其平均值分别为5.25 ℃、29.37 ℃·月、35.88 ℃·月。

表4 地中海气候区林线处气候指标的平均值和标准差Table 4 Mean and standard deviation of climatic variables at the mediterranean timberlines in the Eurasian continent

2.2.4 温带海洋性和大陆性气候区

温度海洋型气候区的林线主要分布在阿尔卑斯山、喀尔巴阡山和苏格兰的山体,林线高度从山体边缘的1600—1700m升高至山体内部的2200—2400m[45]。温带大陆性气候区林线主要分布在乌拉尔山南部、天山、阿尔泰山、我国华北地区、东北亚和日本北海道地区。林线高度纬向递减趋势明显,在乌拉尔山南部的Yaman-Tow Mt.,林线高度仅为1250m[46],到昆仑山北翼乌依塔克林线高度可升高至3400m[47]。如表5所示,这两个气候区林线位置标准差最小的气候指标均为:ABT,WI和MTWM。但是气候指标平均值相差较大,前者分别为:3.73 ℃、16.14 ℃·月和10.31 ℃,后者分别为:4.01 ℃、21.47 ℃·月、MTWM:12.24 ℃。

表5温带海洋性气候区和大陆性气候区林线处气候指标的平均值和标准差

Table5MeanandstandarddeviationofclimaticvariablesatthetimberlinesofthetemperatemarineandcontinentalzoneintheEurasiancontinent

统计项Statisticalitems气候区(样本数)Climaticzone(samplenumber)气候指标ClimaticvariablesWI/(℃·月)CI/(℃·月)ABT/℃MTWM/℃MTCM/℃ART/℃AMT/℃平均值Mean温带海洋性16.1452.773.7310.31-5.8816.191.95标准差Standarddeviation气候(67)1.001.490.741.462.582.351.63平均值Mean温带大陆性21.4794.934.0112.24-16.2728.52-1.12标准差Standarddeviation气候(55)0.983.100.751.314.991.042.41

2.2.5 亚寒带相对海洋性和大陆性气候区

亚寒带地区的林线主要分布在海洋性气候影响显著的斯堪的纳维亚山脉东西两侧和大陆性气候影响显著的斯堪的纳维亚山北部、乌拉尔山、中西伯利亚高原。其中相对海洋性气候区林线高度由沿海地区的400—500m,升高至山体内部的1200m[18,48]。相对大陆性气候区林线高度由乌拉尔山北部的Narodnaya的400—500m[46],升高至阿尔泰山Kuray山区的2240m[49]。根据表6,相对海洋性气候区林线位置变化最小的3个气候指标分别是:ABT:2.98 ℃、WI:12.55 ℃·月、CI:80.88 ℃·月;而相对大陆性气候区分别是:ABT:2.99 ℃,WI:15.47 ℃·月,MTWM:12.06 ℃。

表6亚寒带相对海洋性气候区和相对大陆性气候区林线处气候指标的平均值和标准差

Table6MeanandstandarddeviationofclimaticvariablesatthetimberlinesofthesubarcticmarineandcontinentalzoneintheEurasiancontinent

统计项Statisticalitems气候区(样本数)Climaticzone(samplenumber)气候指标ClimaticvariablesWI/(℃·月)CI/(℃·月)ABT/℃MTWM/℃MTCM/℃ART/℃AMT/℃平均值Mean相对海洋性12.5580.882.9810.16-10.5120.67-0.69标准差Standarddeviation气候(14)0.350.550.330.581.010.990.76平均值Mean相对大陆性15.47162.282.9912.06-26.8838.94-7.23标准差Standarddeviation气候(56)1.294.621.061.547.437.183.87

2.2.6 高原温带和亚寒带气候区

青藏高原地区的林线主要分布在高原温带湿润型的藏东川西山地针叶林带、高原温带半干旱型的青东祁连山地草原与针叶林地带和高原亚寒带半干旱型的喀喇昆仑山-西昆仑山地区。高原温带和亚寒带地区林线高度分别为3700—4900m[50-52]和3500—4300m[42]。如表7所示,青藏高原林线位置标准差最小的气候指标均为:ABT、WI和MTWM。但是气候指标平均值相差较大,温带地区为:ABT:4.04 ℃、WI:18.02 ℃·月、MTWM:10.3 ℃;亚寒带地区为: ABT:4.18 ℃、WI:23.1 ℃·月、MTWM:12.5 ℃。

表7 青藏高原温带气候区和亚寒带气候区林线处气候指标的平均值和标准差Table 7 Mean and standard deviation of climatic variables at the timberlines in the Tibetan Plateau of the Eurasian continent

3 结论与讨论

本研究首先表明无论哪个气候区,林线高度如何变化,以年生物温度和温暖指数为代表的生长季温度都具有最小的标准差,表明了它们最为稳定,是限制林线高度分布的主导气候因子。这与近年来Körner等[7,9,16]对全球林线变化的研究得出的结论,即生长季温度决定了林线高度的分布是一致的。从生理生态机理来说,生长季温度过低不仅限制碳固定[16,53],影响树木的生长[7,28],也会通过突发性事件如夏季霜冻对树木的繁殖更新产生干扰[54]。由于低温环境下,光吸收作用降低之前,温度已经制约了植物细胞的形成和组织的分化,因此相比碳固定,生长季温度对植物增长率的影响近年来被认为是全球林线形成的关键[8,28]。但是在区域尺度和山系尺度,生长季温度如何影响林线还需要进一步的探讨。

本研究还发现除生长季温度外,在亚热带湿润气候区、温带海洋性气候区、温带大陆性气候区、亚寒带大陆性气候区、高原温带气候区和高原亚寒带气候区,最热月温度也发挥了重要的作用;在地中海地区和亚寒带海洋性气候区寒冷指数对林线的存在也很重要;而在热带湿润气候区,年均温与林线存在的相关性也较为明显。另外在不同气候区,限制林线高度的温度值变化较大,如在温带海洋性气候区,限制林线高度的温度指标分别为ABT:3.73 ℃,WI:16.14 ℃·月,MTWM:10.31 ℃;但是在温带大陆性气候区,这三个指标的数值分别升高至4.01 ℃, 21.47 ℃·月和12.24 ℃,均高于前者。

先前的许多研究通常使用某一个均温指标,如MTWM 10 ℃、 ABT 3 ℃,WI 15 ℃·月来指示林线的位置[10-15]。但是本研究发现这3个指标仅适用于部分气候区。如图3所示,林线位置平均MTWM仅在温带海洋性气候,亚寒带海洋性气候区和高原温带地区接近10 ℃,平均ABT仅在亚寒带气候区接近3 ℃,平均WI仅在亚寒带大陆性气候区内接近15 ℃·月。而在温带大陆性气候区、高原亚寒带地区和地中海气候区,这些指标的平均值都出现了不同程度的升高,其中地中海气候区的升高幅度最高,MTWM、ABT和WI分别升高了3.3 ℃,2.25 ℃和14.37 ℃·月(图3)。这也说明了在这些气候区林线的实际高度低于基于均温预测的理论值,造成林线高度降低和温度升高的原因可能有如下几个:

图3 欧亚大陆不同气候区内林线位置平均WI,ABT和MTWM的比较Fig.3 Comparison of the average WI, ABT and MTWM at timberline positions in different climatic zones in the Eurasian continentWI, warmth index, 温暖指数; AMT, annual biotemperature, 年生物温度; MTWM, mean temperature of the warmest month, 最热月温度

首先,环境异质性致使地中海气候区缺乏常规的云杉、冷杉等林线建群种,导致林线实际高度的降低。地中海气候区内巴尔干半岛、亚平宁半岛的北部山地通常为水青冈属,缺乏云杉、冷杉等暗针叶林[55]。这导致了地中海地区实际林线高度低于林线均温如MTWM 10 ℃等预测的理论值。如巴尔干半岛Mt. Ossa(39.79°N)林线高度仅为1800m[55],而使用最热月温度10 ℃估算其林线高度约为2730 m,前者比后者低930 m。物种缺乏的原因至今并无定论,可能与全新世气候的改变、人类的影响及火灾等因素有关[56]。

其次,季风、山体效应和局部气候综合作用造成青藏高原内部降水相对丰富的南坡和谷地出现了成片的森林带,其分布上限低于气候林线。青藏高原地势的特点是由外缘向内部升高,青藏高原内部山体基面高度高达4000m,产生了强烈山体效应,导致高原内部温度高于高原外缘同海拔自由大气的温度[57]。根据姚永慧和张百平[58-59]的研究,在4500m海拔上,青藏高原内部温度比四川盆地高3.58—6.63 ℃,导致气候林线(根据最热月温度10 ℃估算)升至4600—5000m[60-62]。但是高原内部高寒干旱的气候致使整体缺乏森林带,只是在克什米尔喜马拉雅山西部降水相对丰富的南坡和谷地出现了糙皮桦(Betulautilis)、栒子叶柳(Salixkarelinii)以及刺柏属(J.turkestanica)矮曲林带[42,63],林线高度为3600—4300m[42],低于气候林线。

最后,在温带大陆性气候区,林线高度与降水量呈现负相关,根据Malyshev[49]的研究,阿尔泰山西北部相对湿润,林线高度为1700—1900m,而东南部相对干燥,林线高度为2100—2465m。这就意味着该地区林线高度的降低可能与降水量的增加有关。但是从全球尺度来看,降水的变化主要与局部的山地气候有关,与山体海拔并没有密切的相关[64],因此本研究没有将年降水或者湿度作为与林线存在有关的气候指标之一。但是值得注意的是,林线存在需要满足一个基本的前提,那就是降水量或者湿度状况满足森林带存在的基本需要。对于暗针叶林来说,年平均相对湿度需要大于60%,年降水量大于600mm[65]。

另外,基于WorldClim全球气候数据集估算高海拔山区林线温度与实际林线温度可能存在一定的误差。但是由于大部分林线位置缺乏气象台站,无法直接获取林线温度,而本文的结果是所在区域多个林线温度的平均值,在很大程度上降低了由于数据误差带来的结果不确定性。实际上,基于WorldClim估算的区域温度的平均值在全球尺度和区域尺度接近实际林线温度,比如由WorldClim估算的全球林线生长季平均温度为6.4 ℃[9],与实测的生长季平均温度6.7 ℃[7]仅相差0.3 ℃;估算的北方针叶林的北界是最热月温度11.7 ℃,这一温度与Malyshev计算的北方针叶林的北界11.2 ℃[49]仅相差0.5 ℃。

[1] Troll C. The Upper Timberlines in Different Climatic Zones. Arctic and Alpine Research, 1973, 5(3): A3-A18.

[2] Hoch G, Körner C. Growth and carbon relations of tree line forming conifers at constant vs. variable low temperatures. Journal of Ecology, 2009, 97(1): 57-66.

[3] Kollas C, Randin C F, Vitasse Y, Körner C. How accurately can minimum temperatures at the cold limits of tree species be extrapolated from weather station data? Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2014, 184: 257-266.

[4] Harsch M A, Bader M Y. Treeline form—a potential key to understanding treeline dynamics. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2011, 20(4): 582-596.

[5] Kullman L. Tree line population monitoring ofPinussylvestrisin the Swedish Scandes, 1973-2005: implications for tree line theory and climate change ecology. Journal of Ecology, 2007, 95(1): 41-52.

[6] Miehe G, Miehe S, Koch K, Will M. Sacred forests in Tibet——using geographical information systems for forest rehabilitation. Mountain Research and Development, 2003, 23(4): 324-328.

[7] Körner C, Paulsen J. A world-wide study of high altitude treeline temperatures. Journal of Biogeography, 2004, 31(5): 713-732.

[8] Körner C. Alpine treelines: functional ecology of the global high elevation tree limits. Basel: Springer 2012: 33-56.

[9] Paulsen J, Körner C. A climate-based model to predict potential treeline position around the globe. Alpine Botany, 2014, 124(1): 1-12.

[10] Daubenmire R. Alpine timberlines in the Americas and their interpretation. Butler University Botanical Studies, 1954, 11(8/17): 119-136.

[11] Grace J. Plant response to wind. London: Academic Press, 1977: 1-204.

[12] Holdridge L R. Determination of world plant formations from simple climatic data. Science, 1947, 105(2727): 367-368.

[13] Harris S A. Comments on the Application of the Holdridge System for Classification of World Life Zones as Applied to Costa Rica Arctic and Alpine Research 1973, 5(3): A187-A191

[14] Ohsawa M. An interpretation of latitudinal patterns of forest limits in South and East Asian mountains. Journal of Ecology, 1990, 78(2): 326-339.

[15] Fang J Y, Ohsawa M, Kira T. Vertical vegetation zones along 30°N latitude in humid East Asia. Vegetatio, 1996, 126(2): 135-149.

[16] Hoch G, Körner C. Global patterns of mobile carbon stores in trees at the high-elevation tree line. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2012, 21(8): 861-871.

[17] Shi P, Körner C, Hoch G. A test of the growth-limitation theory for alpine tree line formation in evergreen and deciduous taxa of the eastern Himalayas. Functional Ecology, 2008, 22(2): 213-220.

[18] Holtmeier F K. Mountain timberlines ecology, patchiness, and dynamics, 2nd edn. New York: Springer Verlag, 2009: 49-58.

[19] Ohsawa M, Nainggolan P H J, Tanaka N, Anwar C. Altitudinal zonation of forest vegetation on Mount Kerinci, Sumatra: With comparisons to zonation in the temperate region of east Asia. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 1985, 1(3): 193-216.

[20] Janzen D H. Why Mountain Passes are Higher in the Tropics. The American Naturalist, 1967, 101(919): 233-249.

[21] Bader M Y, Ruijten J J A. A topography-based model of forest cover at the alpine treeline in the tropical Andes. Journal of Biogeography, 2008, 35(4): 711-723.

[22] Holtmeier F K, Broll G, Müterthies A, Anschlag K. Regeneration of trees in the treeline ecotone: northern Finnish Lapland. Fennia, 2003, 181(2): 103-128.

[23] Peterson D L. Climate, limiting factors and environmental change in high-altitude forests of Western North America//Beniston M, Innes J L, eds. The Impacts of Climate Variability on Forests. Berlin Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 1998: 191-208.

[24] Gansert D. Treelines of the Japanese Alps——altitudinal distribution and species composition under contrasting winter climates. Flora -Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants, 2004, 199(2): 143-156.

[25] Miehe G, Miehe S. Zur oberen Waldgrenze in tropischen Gebirgen. Phytocoenologia, 1994, 24(1/4): 53-110.

[26] Odland A. Differences in the vertical distribution pattern ofBetulapubescensin Norway and its ecological significance. Paläoklimaforschung, 1996, 20: 43-59.

[27] Jobbágy E G, Jackson R B. Global controls of forest line elevation in the northern and southern hemispheres. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2000, 9(3): 253-268.

[28] Körner C. A re-assessment of high elevation treeline positions and their explanation Oecologia, 1998, 115(4): 445-459.

[29] Hijmans R j, Cameron S e, Parra J l, Jones P g, Jarvis A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology, 2005, 25(15): 1965-1978.

[30] Kessler M, Kluge J, Hemp A, Ohlemüller R. A global comparative analysis of elevational species richness patterns of ferns. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2011, 20(6): 868-880.

[31] Szabo N D, Algar A C, Kerr J T. Reconciling topographic and climatic effects on widespread and range-restricted species richness. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2009, 18(6): 735-744.

[32] Casalegno S, Amatulli G, Camia A, Nelson A, Pekkarinen A. Vulnerability ofPinuscembraL. in the Alps and the Carpathian mountains under present and future climates. Forest Ecology and Management 2010, 259(4): 750-761.

[33] Kira T. Forest Ecosystems of East and Southeast Asia in a global perspective. Ecological Research, 1991, 6(2): 185-200.

[34] Harsch M A, Hulme P E, McGlone M S, Duncan R P. Are treelines advancing? A global meta-analysis of treeline response to climate warming. Ecology Letters, 2009, 12(10): 1040-1049.

[35] Tranquillini W. Physiological ecology of the Alpine timberline. Berlin Heidelberg and New York: Springer-Verlag, 1979

[36] Fang J Y, Lechowicz M J. Climatic limits for the present distribution of beech (FagusL.) species in the world. Journal of Biogeography, 2006, 33(10): 1804-1819.

[37] 王襄平, 张玲, 方精云. 中国高山林线的分布高度与气候的关系. 地理学报, 2004, 59(6): 871-879.

[38] Belda M, Holtanová E, Halenka T, Kalvová J. Climate classification revisited: from Koppen to Trewartha. Climate Research, 2014, 59(1): 1-13.

[39] Trewartha G T, Horn L H. An Introduction to Climate. 5th ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 1980:

[40] 郑度. 中国生态地理区域系统研究. 北京: 商务印书馆, 2008

[41] 中国科学院青藏高原综合科学考察队. 西藏植被. 北京: 科学出版社, 1988

[42] Schickhoff U. The Upper timberline in the Himalayas, Hindu Kush and Karakorum: a review of geographical and ecological aspects//Broll G and Keplin B. Mountain Ecosystems: Studies in Treeline Ecology. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2005: 275-354.

[43] Oka S. Controlling Factors of the Forest Limit Altitude in Japanese Mountains. Journal of Geography, 1991, 100(5): 673-696.

[44] 李文华, 冷允法, 胡涌. 云南横断山区森林植被分布与水热因子相关的定量化研究//中国科学院青藏高原综合科学考察队. 青藏高原研究-横断山考察专集(一). 昆明: 云南人民出版社, 1983: 185-205.

[45] Ellenberg H. Vegetation ecology of central Europe. 4th ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988

[46] Henning I. Horizontal and veritcal arrangement of vegetation in the Ural-System//Troll C. Geoecology of the High Mountain Regions of Euroasia. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag Gmbh, 1972: 264-275.

[47] 郑远长. 青藏高原垂直自然带结构类型研究. 云南地理环境研究, 1997, 9(2): 43-52.

[48] Dalen L, Hofgaard A. Differential regional treeline dynamics in the Scandes Mountains. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 2005, 37(3): 284-296.

[49] Malyshev L. Levels of the upper forest boundary in Northern Asia. Vegetatio, 1993, 109(2): 175-186.

[50] 陈桂琛, 彭敏, 黄荣福, 卢学峰. 祁连山地区植被特征及其分布规律. 植物学报, 1994, 36(1): 63-72.

[51] 刘华训. 我国山地植被的垂直分布规律. 地理学报, 1981, 36(3): 267-279.

[52] Miehe G, Miehe S, Vogel J, Co S, Duo L. Highest treeline in the northern hemisphere found in southern Tibet. Mountain Research and Development, 2007, 27(2): 169-173.

[53] Stevens G C, Fox J F. The Causes of Treeline. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 1991, 22: 177-191.

[54] Wardle P. New Zealand timberlines. 1. Growth and survival of native and introduced tree species in the Craigieburn Range, Canterbury. New Zealand Journal of Botany, 1985, 23(2): 219-234.

[55] Grebenshchikov O S. Vegetation structure in the high mountains of the Balkan Peninsula and the Caucasus, USSR. Arctic and Alpine Research, 1978, 10(2): 441-447.

[56] Vescovi E, Ammann B, Ravazzi C, Tinner W. A new Late-glacial and Holocene record of vegetation and fire history from Lago del Greppo, northern Apennines, Italy. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 2010, 19(3): 219-233.

[57] 郑度, 李炳元. 青藏高原自然环境的演化与分异. 地理研究, 1990, 9(2): 1-10.

[58] Yao Y H, Zhang B P. MODIS-based air temperature estimation in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau and neighboring areas. Journal of Geographical Sciences, 2012, 22(1): 152-166.

[59] 姚永慧, 张百平. 基于MODIS数据的青藏高原气温与增温效应估算. 地理学报, 2013, 68(1): 95-107.

[60] 姚永慧, 徐美, 张百平. 青藏高原增温效应对垂直带谱的影响. 地理学报, 2015, 70(3): 407-419.

[61] Yao Y H, Zhang B P. The mass elevation effect of the Tibetan Plateau and its implications for Alpine treelines. International Journal of Climatology, 2014, 35(8): 1833-1846.

[62] Yao Y H, Zhang B P. A Preliminary Study of the Heating Effect of the Tibetan Plateau. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(7): e68750.

[63] Liang E Y, Dawadi B, Pederson N, Eckstein D. Is the growth of birch at the upper timberline in the Himalayas limited by moisture or by temperature? Ecology 2014, 95(9): 2453-2465.

[64] Körner C. The use of ‘altitude’ in ecological research. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2007, 22(11): 569-574.

[65] Li W H, Chou P. The Geographical Distribution of the Spruce-Fir Forest in China and Its Modelling. Mountain Research and Development, 1984, 4(3): 203-212.