Towards a Semantic Explanation for the(Un)acceptability of (Apparent) Recursive Complex Noun Phrases and Corresponding Topical Structures

2018-01-25CaimeiYang

Caimei Yang

Soochow University, China

0. Introduction

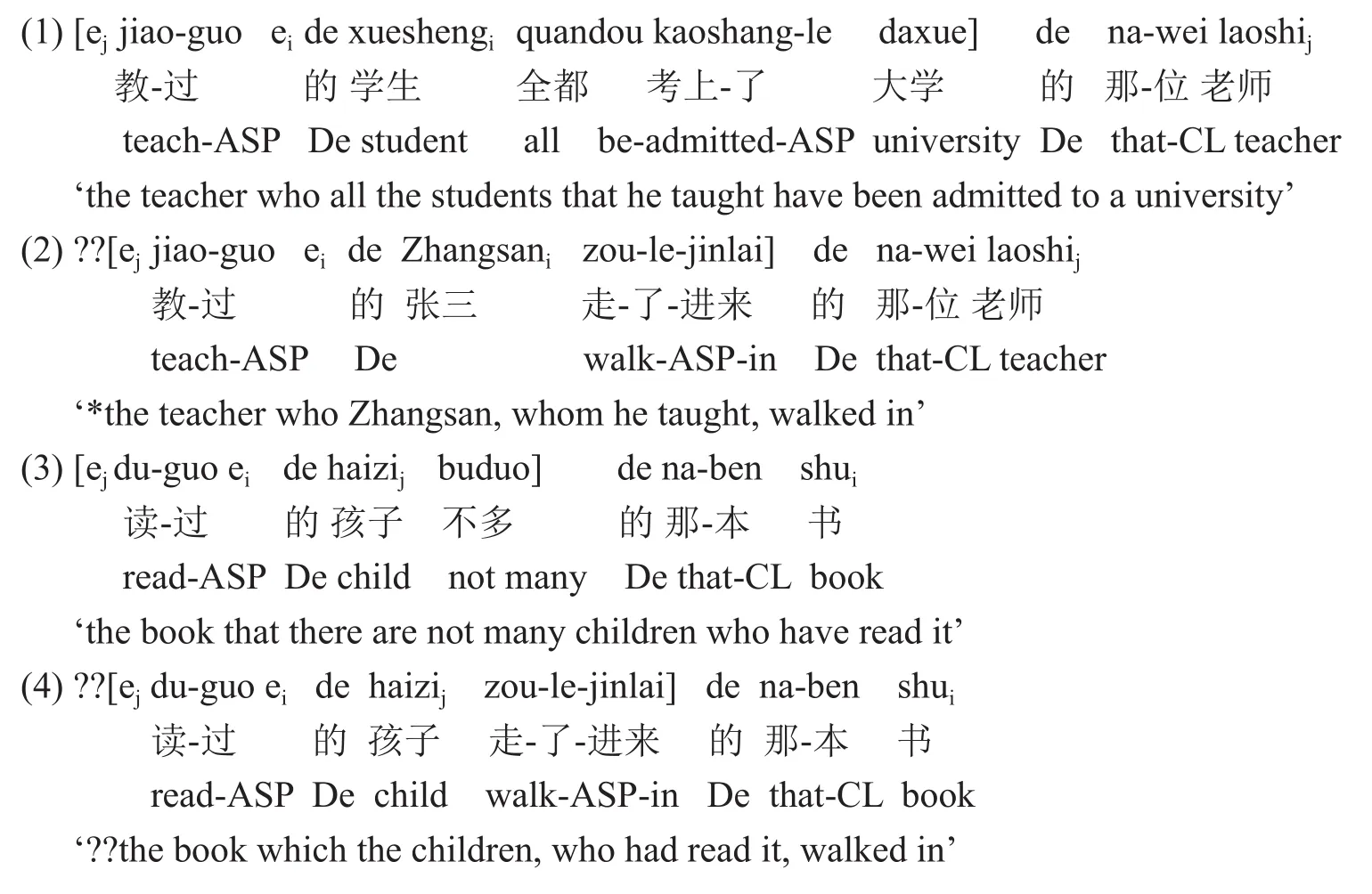

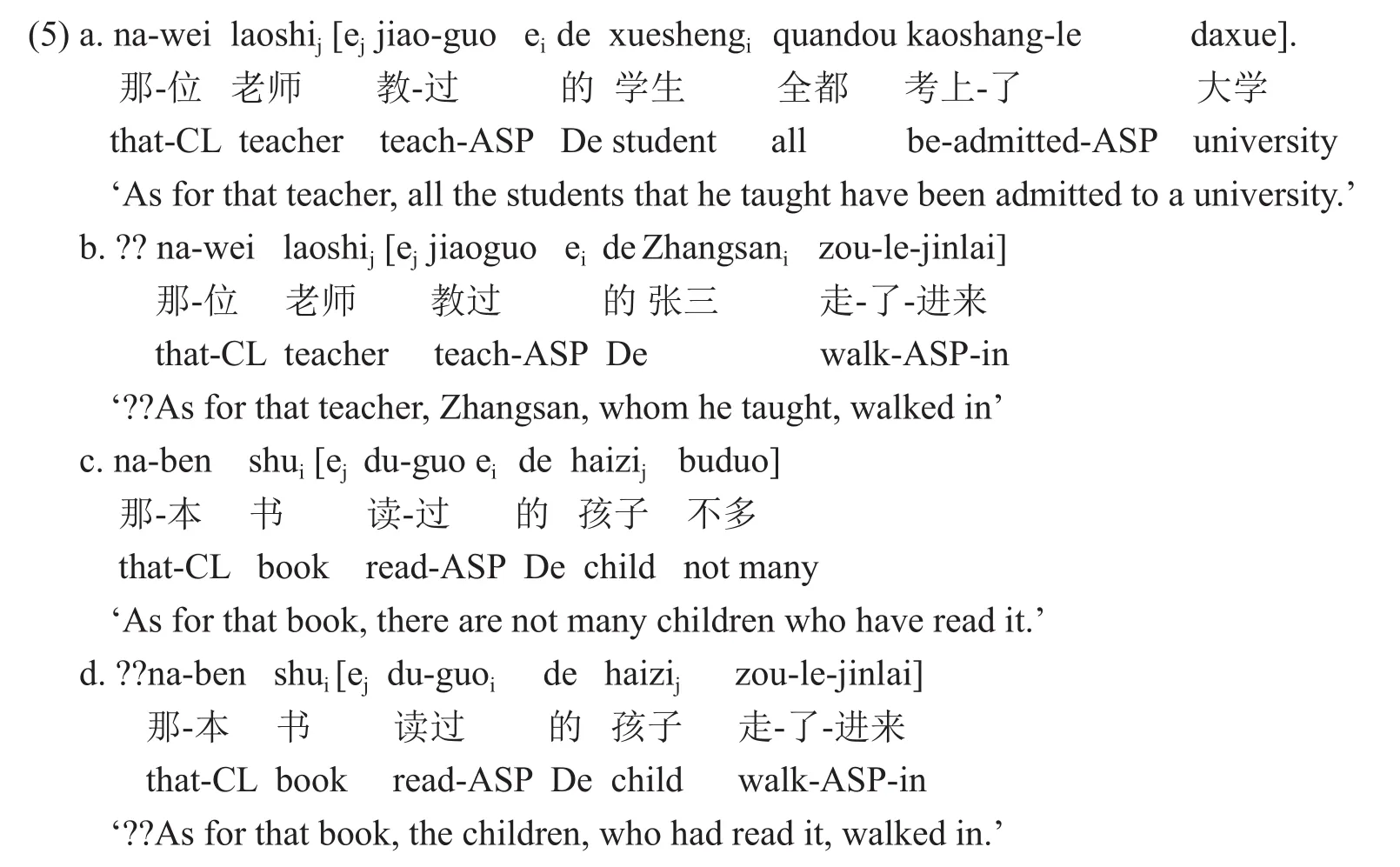

(1-4) are (un)acceptable (apparent) recursive relative structures in Chinese (See Chomsky,1957, 2010; Fitch, 2010; Lobina, 2017 about “recursive” phenomena in languages).The acceptability-unacceptability contrast between (1) and (2) and the acceptabilityunacceptability contrast between (3) and (4) have puzzled many linguists over the past few dozen years, because though their syntactic structures are apparently the same,they are different in acceptability. All of the expressions in (1-4) go against the famous“Complex Noun Phrase Principle” in syntax, but they have different acceptability.

Many linguists (e.g. Xu & Langendoen, 1985; Xu, 2003, 2006; Huang, 1992; Yang,2013) have mentioned corresponding situations in topicalization, as shown in (5).

Xu and Langendoen (1985, pp. 14-15) propose that the differences in acceptability in the above expressions can be attributed to the semantic specificity vs. nonspecificity distinction of the inner complex NPs. In their opinion, the inner complex NPjiaoguo de xuesheng (教过的学生)‘the students whom (he) taught’ in (1) and (5a) is understood as nonspecific while the inner complex NPjiaoguo de Zhangsan (教过的张三)‘Zhangsan,whom (he) taught’ in (2) and (5b) is understood as specific. Similarly, the inner complex NPduguo de haizi (读过的孩子)‘the children who have read (it)’ in (3) and (5c) is understood as nonspecific, while the inner complex NPduguo de haizi (读过的孩子)‘the children, who have read (it)’ in (4) and (5d) is understood as specific. Huang (1992) also provides similar examples and supports the semantic specificity vs. nonspecificity account for the contrasts in the above expressions.

However, (4) can be extended into (6), and (5d) can be extended into (7); and then (6)and (7) become much more acceptable in a bigger context of contrast. It is this context of contrast that makes us easily conjure up a rather complicated situation involving two books and four groups of people in (6) and (7). Just like (4) and (5d), the inner complex NPduguo de haizi (读过的孩子)in (6-7) also denotes specificity. This means that the difference in acceptability cannot be totally attributed to the specificity-nonspecificity distinction.

Xu (2003, p. 142) also realizes that the specific-nonspecific distinction sometimes fails to explain the facts in Chinese, so he points out that the specific-nonspecific distinction may not be pertinent and as such, the phenomenon needs a new explanation.

In this paper, I will present a new analysis of the contrasts in acceptability of the above expressions. The acceptability-unacceptability contrasts in the Chinese relative structures in (1-4) and (6) will be explained with the characterization condition mentioned by Lyons (1977, p. 761). This will be done by showing that the acceptability-unacceptability contrasts are in correspondence with the satisfaction-dissatisfaction contrasts of the characterization condition, which themselves are in correspondence with the restrictivenonrestrictive contrasts of the inner relative clauses, which, in turn, are in correspondence with the reducibility-irreducibility contrasts of the head NPs of the relative clauses.

Similarly, the acceptability-unacceptability contrasts in the corresponding Chinese topical structure in (5) and (7) will be explained with the aboutness condition mentioned in Xu and Langendoen (1985) and Xu (2003, 2006), by showing that the acceptability-unacceptability contrasts in (5) and (7) are in correspondence with the satisfaction-dissatisfaction contrasts of the aboutness condition, which themselves are in correspondence with the restrictive-nonrestrictive contrasts of the relative clauses, which,in turn, are in correspondence with the reducibility-irreducibility contrasts of the head NPs of the relative clauses.

1. The Characterization Condition in Relative Clauses and the Aboutness Condition in Topical Structures

Jackendoff (1972, pp. 61-62) says that “a relative clause can be thought of as a syntactic device that enables the language to express new and complex properties, properties for which there may be no single lexical item.” According to Lyons (1977, p. 761),“Restrictive relative clauses, likethe man who/that broke the bank at Monte Carlo (is a mathematician), are used, characteristically, to provide descriptive information which is intended to enable the addressee to identify the referent of the expression within which they are embedded. For example,the man who/that broke the bank at Monte Carlotells the addressee of which person it is being asserted that he is a mathematician.”

These ideas clearly show that the semantic function of a relative clause is to characterize its head NP by describing the properties of the head NP. This is a necessary and universal semantic function of relative clauses and, therefore, a universal semantic licensing condition of all relative clauses. This characterization function can be further divided into two sub-functions: description and identification, related to two kinds of relative clauses: restrictive and nonrestrictive relative clauses. A restrictive is used to identify an entity (or a set of entities), denoted by the head NP, from others via the description of a property expressed with the relative clause. Here are more examples: in Chinese,ren (人)1‘person1’ can be distinguished fromren (人)2‘person2’ via their different properties such asxianzai zheng xiexin de(ren1)(现在正写信的(人1))‘(the person1)who is writing a letter’ andxianzai zheng shuijiao de(ren2)(现在正睡觉的(人2))‘(the person2) who is sleeping’. A nonrestrictive is used to describe an entity (a set of entities)without the need to identify the entity (or the set of entities) from others. For example,the relative clausedi da wu bo de(地大物博的)‘which is big and rich’ in the complex NP phrasedi da wu bo de Zhongguo (地大物博的中国)‘China, which is big and rich’is used to describe the head NPZhongguo‘China’, which is a proper name and need not be identified from other countries. In conclusion, the descriptive function is basic, and the identifying function is a further aim. To put it in another way, all relative clauses are to describe the properties of the head NPs, but not all relative clauses are to identify their head NPs from others.

Xu and Langendoen (1985, p. 1) claim that “[Chinese] topic structure(s) are syntactically characterized by the rule schema S’→X{S, S’}, where…S or S’, the comment, is another topic structure or a sentence which is independently well-formed”and that, in topic structures, “some constituent of the comment, or the comment as a whole, must be related to the topic”. To put it in another way, there are two licensing conditions on Chinese topicalization: one is the syntactic well-formedness condition,and the other is the semantic aboutness condition, which requires that the topicalized NP be related to the comments semantically. Although the syntactic condition of English topicalization is different from that of Chinese topicalization (see the details in Xu &Langendoen, 1985; Xu, 2003, 2006), both English and Chinese topicalizations must satisfy the same semantic aboutness condition. The aboutness condition is a universal semantic licensing condition of all topical structures. Take the Chinese examples in (8a)and their English translations for example. In (8), the comment parthuo xiaofangdui pumie-le(火消防队扑灭了)‘the fire brigade put (it) out’ is about the topicNa-chang huo(那场火) ‘that fire’.In (8b), the comment partyezi da (叶子大)‘(its) leaves are big’ is about the topiczhe-ke shu (这棵树)‘this tree’.

2. The Restrictive-Nonrestrictive Distinction in Correspondence With the Satisfaction-Dissatisfaction of the Characterization/Aboutness Condition

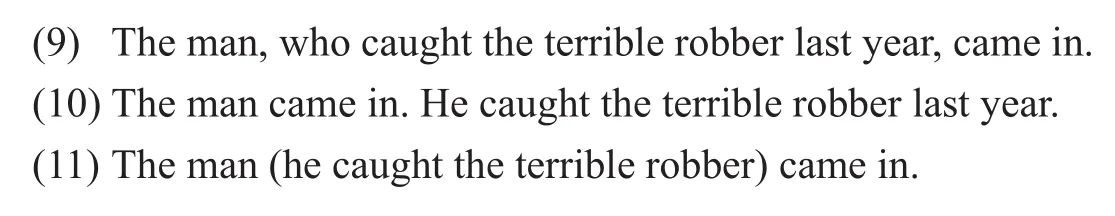

Many researchers think that, unlike the restrictive, the nonrestrictive doesn’t form a constituent with its antecedent, but forms another main clause. This is called the Main Clause Hypothesis (Ross, 1967; Sells, 1985a, b; Demirdache, 1991). Sells (1985a, b)treats nonrestrictives as a phenomenon of discourse anaphora at an intermediate level of discourse structure. In a broader perspective, as pointed out by De Vries (2002), the nonrestrictives are in a state of “orphanage”, that is, the nonrestrictive relative clause is not a constituent of the matrix sentence, but an “orphan”. In a word, the restrictive relative clause is a constituent of the matrix clause, while the nonrestrictive relative clause is separated as an “orphan” from the matrix clause or sentence.

According to the Main Clause Hypothesis, (9) is essentially equal to (10). According to the “orphanage” hypothesis, which is tantamount to the Main Clause Hypothesis in essence, the nonrestrictivewho caught the terrible robber last yearin (9) is not a constituent of the matrix sentenceThe man came inbut an “orphan” straying outside it.We may put this “orphan” in parentheses, as shown in (11).

The NPthe terrible robberin neither (10) nor (11) can be relativized or topicalized, as shown in (12-13), sincethe terrible robberin neither (10) nor (11) is related to the matrix sentenceThe man came in. Therefore, the head NP in neither (12a) nor (13a) can be characterized by the relative clause. And the comment in neither (12b) nor (13b) is about the topic.

Under the Main Clause Hypothesis or the “orphanage” hypothesis, (9) is equal to (10)or (11). Therefore, the NPthe terrible robber in the nonrestrictive clause in (9) cannot be relativized into (14a). Similarly, the NPthe terrible robber in the nonrestrictive clause in(9) cannot be topicalized into (14b).

But (15a) is different. In it, the relative clausewho can catch that terrible robberis more reasonably understood as a restrictive modifying and identifying the head NPany man, and so the NPthe terrible robberin the relative clause can be relativized into (15b)with the help of a resumptive pronoun. In this case, the head NPthe terrible robbercan be characterized by the recursive relative clausewhom any man who can catch him must be a herosince the restrictivewho can catch himis a constituent of the whole recursive relative clause. So, the characterization condition of relative clause is satisfied. Similarly,the NPthe terrible robberin the relative clause can be topicalized into (15c) with the help of a resumptive pronoun. Here, the recursive comment partany man who can catch him must be a herois about the NPthe terrible robber. So, the aboutness condition is satisfied.

In conclusion, the NP in an English restrictive relative clause can be further relativized and topicalized since the restrictive relative clause is thought to be a constituent of the matrix clause, while the NP in a nonrestrictive relative cause cannot since the nonrestrictive relative clause is not a constituent of the matrix clause. This leads to the satisfaction/dissatisfaction of the characterization condition of relative clauses and the aboutness condition of topic structures.

2.1 The restrictive-nonrestrictive distinction in correspondence with the reducibilityirreducibility distinction in English

“It is well known that English restrictive relative clauses differ from nonrestrictive relative clauses in phonology, orthography, semantics, and syntax (Jackendoff, 1977; Bache &Jakobsen, 1980; Huddleston, 1984; McCawley, 1988, among others)” (Lin, 2003, p. 1).Lyons (1977, p. 760) says that “nonrestrictive relative clauses are set off from the head NP by commas in written English and are at least potentially distinguishable by rhythm and intonation in the spoken language.” For example, (16a) is thought to be nonrestrictive,while (16b) restrictive.

But this paper proposes that, behind these apparent punctuational or phonological features, the restrictive-nonrestrictive distinction of the English relative clauses is essentially decided by a semantic reducibility-irreducibility distinction of the head NPs of the relative clauses, which is hinted at not only by the head NPs themselves but more importantly by their context. To make it clearer, let’s see the acceptability-unacceptability contrasts in examples (17-20).

In (17a), the complex NPJohn, who had read the bookdenotes a specific person for reason of the proper nameJohn. We cannot have (18) (in which there is no comma between the head NP and the relative clause). That is to say, the proper nameJohnhints that the head NPJohncannot be reduced. It is this irreducibility of the head NP that leads to the existence of a nonrestrictive relative clause. And since (17a) has a nonrestrictive,the bookin it cannot be relativized into the more-apparent-than-real recursive complex NP in (17b) as a result of the dissatisfaction of the characterization condition. In (17b), the inner relative clausewho had read itis just an “orphan”, so the remaining outer relative clausewhich John camecannot characterize the head NPthe book. As a result, the head NPthe bookcannot be characterized by the whole more-apparent-than-real recursive relative clausewhich John, who had read it, came in.Similarly,the bookin (17a)cannot be topicalized into (17c), either, as a result of the dissatisfaction of the aboutness condition.

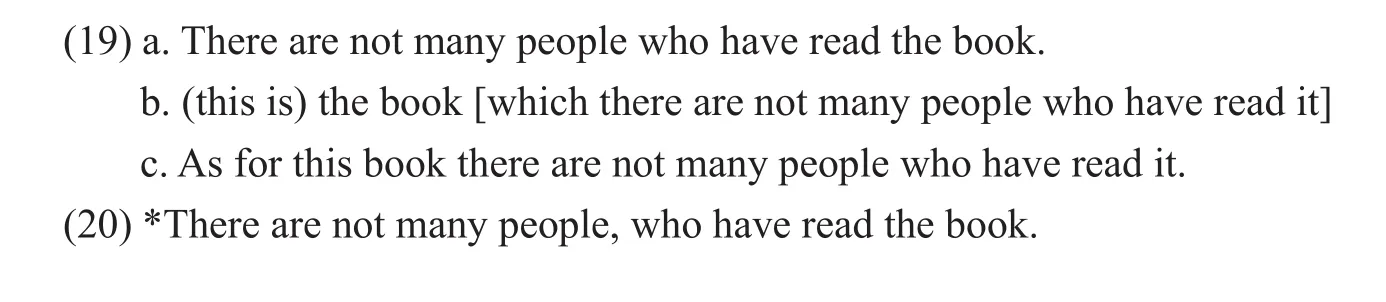

On the other hand, in (19a) the complex NPmany people who have read the bookdenotes some nonspecific persons in the context of a “there be” construction, for we cannot have such expressions asthere is John/this man who has read the bookin the context of a “there be” construction. As a result, (20) is ungrammatical, in that there is a comma between the head NP and the relative clause. That is to say, the head NPmany peopleand the context of the “there be” construction hint that the head NPmany peoplemust be reduced. This reducibility of the head NP of the relative clause only allows for a restrictive. Since the complex NPmany people who have read the bookin (19a) has a restrictive,the bookin it can be relativized into (19b) because of the satisfaction of the characterization condition. Therefore, in (19b), the head NPthe bookcan be characterized by the recursive relative clausewhich there are not many people who have read it.Similarly,the bookin (19a) can be topicalized into (19c) as a result of the satisfaction of the aboutness condition.

From (17-20), it is concluded that, behind the apparent punctuational or phonological features, the restrictive-nonrestrictive distinction of relative clauses is decided by the semantic distinction between the reducibility and irreducibility of the head NPs, which is hinted at not only by the head NPs but more importantly by their context, for example, the context of the “there be” construction.

Take more examples in (21-22). In (21), the lexical array of the complex NPthe men who had read the bookis more likely to denote specific persons in the context of past tense, which usually involves a bigger context like this: “Yesterday I met some men. They all had read the bookGone with the Wind. The men, who had read the book, walked in…”This context makes the head NPthe menirreducible. So, we have (21a), in which there is a comma between the head NP and the relative clause, forming a nonrestrictive. In this case,the bookin (21a) cannot be relativized into the more-apparent-than-real recursive complex NP in (21b) because of the dissatisfaction of the characterization condition.Therefore, in (21b), the head NPthe bookcannot be characterized by the apparent recursive relative clausewhich the men, who had read it, walked in. Similarly,the bookin (21a) cannot be topicalized into (21c) as a result of the dissatisfaction of the aboutness condition.

However, although the lexical array in the complex NPthe menwho had read the bookin the extended expression (22a) is still more likely to denote specific persons in the context of past tense, when it comes to the bigger context of contrast we cannot have(22b). This is because in the bigger context of contrast, the two instances ofthe menmust be reduced by restrictives, as shown in (22a). Since the two complex NPsthe men who had read the bookandthe men who had not read the bookin (22a) have restrictives instead of nonrestrictives,the bookin (22a), which is in the across-the-board situation, can be relativized into the recursive (22c) because of the satisfaction of the characterization condition. Similarly,the bookin (22a) can be topicalized into (22d) as a result of the satisfaction of the aboutness condition.

More similar examples are shown in (23-28).

From the above discussion, we see that, according to the Main Clause Hypothesis, or the“orphanage” hypothesis, a nonrestrictive is another type of main clause, or “orphan”. Therefore,the NP in a nonrestrictive cannot be relativized into an acceptable recursive complex NP since the characterization condition is accordingly unsatisfied, while the NP in the restrictive relative clause can, since the characterization condition is satisfied. Similarly,the NP in a nonrestrictive cannot be topicalized into an acceptable topic structure since the aboutness condition is accordingly unsatisfied, while the NP in the restrictive relative clause can, since the aboutness condition is satisfied. Moreover, the restrictivenonrestrictive distinction of English relative clauses is essentially decided by a semantic reducibility-irreducibility distinction of the head NP, hinted at not only by the head NP itself but more importantly by its context. This is true with Chinese, too, as will be shown below.

2.2 The restrictive-nonrestrictive distinction in correspondence with the reducibilityirreducibility distinction in Chinese

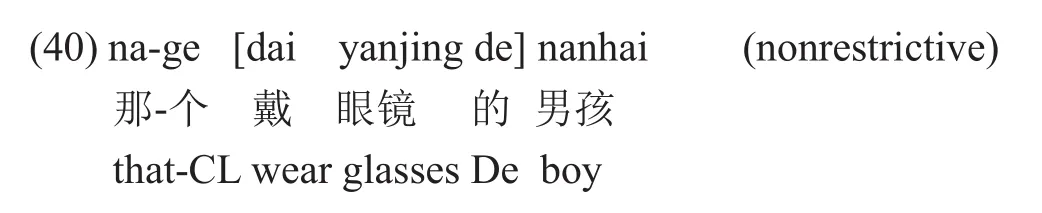

In Chinese, there is no English-like punctuational, phonological, or syntactic distinction of restrictiveness vs. nonrestrictiveness. According to Lin (2003), “Whether or not Chinese has nonrestrictive relative clauses has been very controversial.” Also, it has been claimed that the distinction between restrictiveness and nonrestrictiveness in Chinese is marked through linear order. More specifically, Chao (1968), Hashimoto (1971), and Li(1998) maintain that a Chinese relative clause is interpreted as nonrestrictive if it follows a demonstrative, but as restrictive if it precedes it, as shown below.

Huang’s (1982/1998) account of the examples in (29-30) is in terms of the scope of modification: if the relative clause is in the scope of the demonstrative as in (29), the demonstrative is deictic, and it fixes the reference of the head of the relative clause. The relative clause is then nonrestrictive. But when the demonstrative is in the scope of the relative clause, as in (30), it is used anaphorically on the relative clause. And it is the relative clause, now restrictive, which contributes to determining the reference of the head noun phrase.

On the other hand, Lin (2003, p. 1) claims: “All relative clauses that occur with a determiner should be analyzed as restrictive. However, it is too strong a claim to say that nonrestrictive relative clauses do not exist in Chinese. When the antecedent of a relative clause is a proper name, the nonrestrictive interpretation is allowed if the relative clause describes a more or less permanent or stable property.”

I agree with Lin (2003) that when the antecedent of a relative clause is a proper name, the nonrestrictive interpretation is allowed if the relative clauses describe a more or less permanent or stable property. But I disagree with Lin (2003) when he claims that all relative clauses that occur with a determiner should be analyzed as restrictive. Also, I think the linear order hypothesis in Chao (1968), etc., as shown in (29-30) above, is more apparent than real.

The rationale in Section 2.1 can help us to dig out the distinction between restrictives and nonrestrictives in Chinese. I propose the restrictive-nonrestrictive distinction of Chinese relative clauses is also determined by the semantic reducibility-irreducibility distinction of the head NP of the relative clause, which is also hinted at not only by the head NP itself but more importantly by its context. Let’s see the following examples.

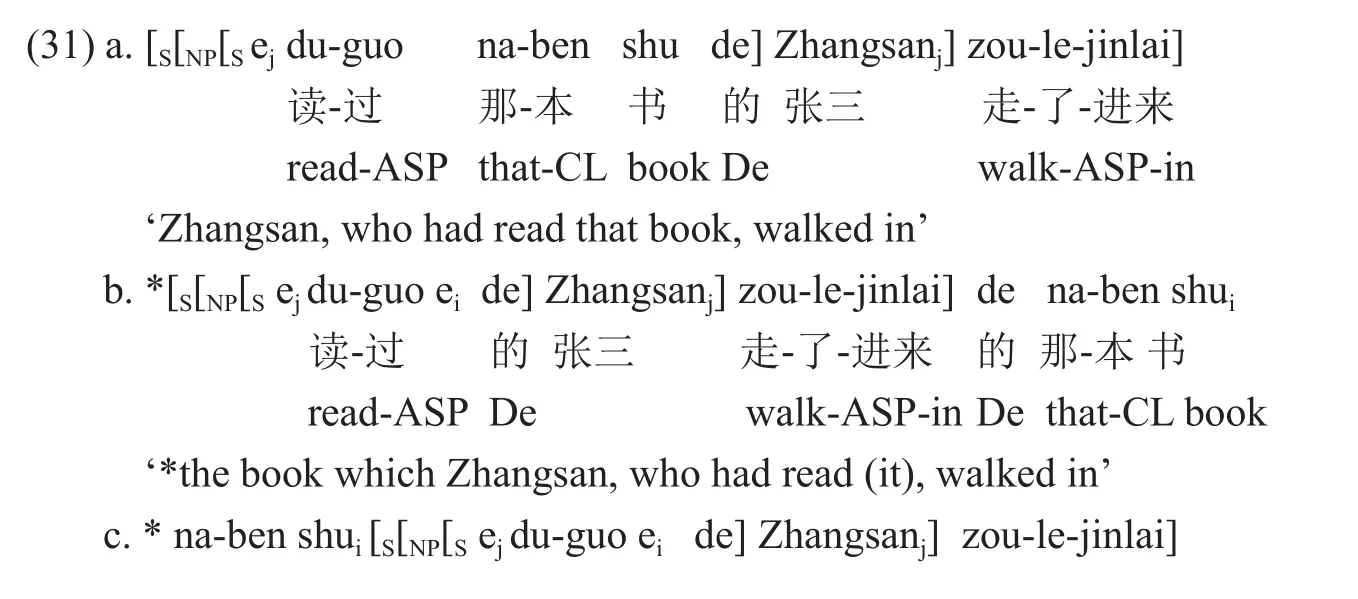

The complex NP in (31a)du-guo na-ben shu de Zhangsan (读过那本书的张三)‘Zhangsan,who had read that book’ denotes a specific person named Zhangsan, and therefore the context of the proper nameZhangsanonly allows for a nonrestrictive. Since the complex NPdu-guo na-ben shu de Zhangsan (读过那本书的张三)in (31a) has a nonrestrictive,the NPna-ben shu(那本书)in it cannot be relativized into the more-apparent-than-real recursive complex NP in (31b) as a result of the dissatisfaction of the characterization condition. In (31b), the inner relative clausedu-guo de(读过的)‘who had read (it)’ is just an “orphan” and therefore the remaining part,Zhangsan zou-le-jinlai de (张三走了进来的)‘which Zhangsan walked in’, cannot characterize its head NPna-ben shu(那本书).Similarly,na-ben shu(那本书)in (31a) cannot be topicalized into (31c) as a result of the dissatisfaction of the aboutness condition.

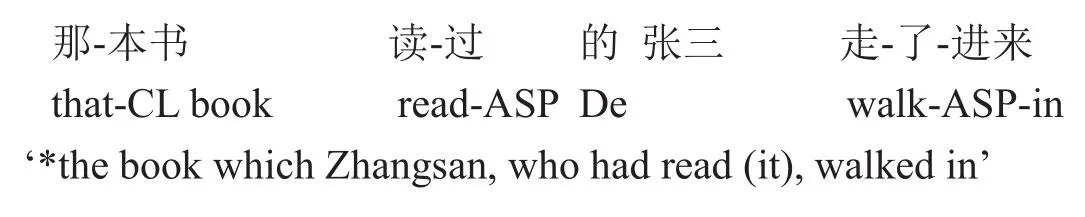

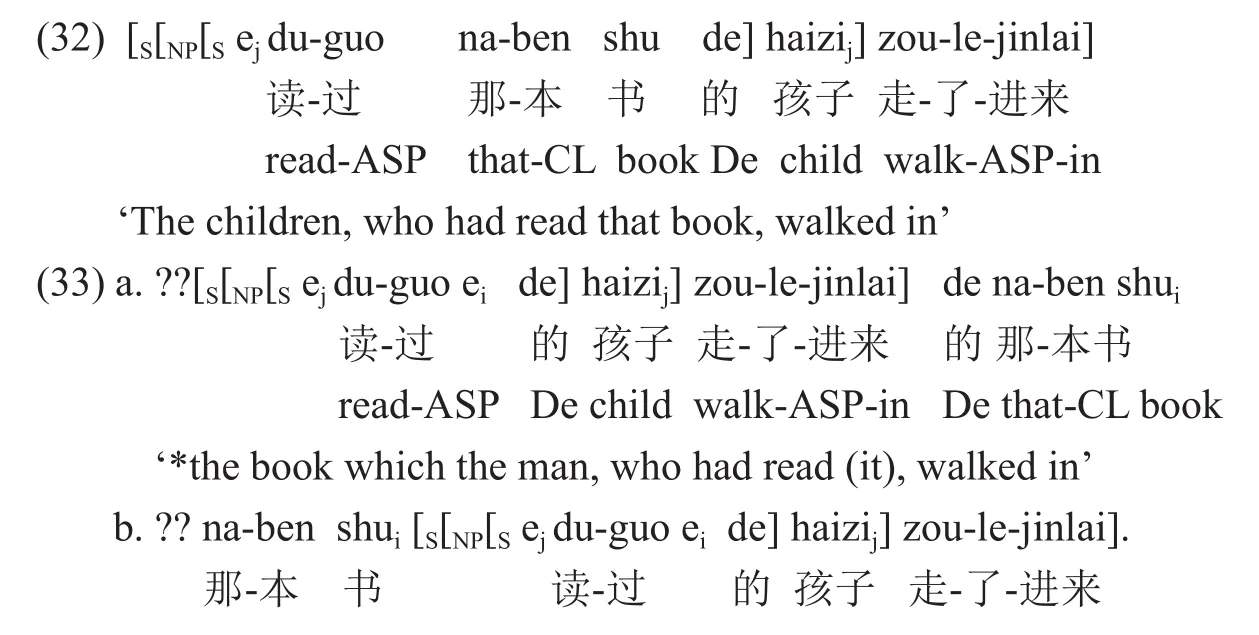

In (32), the lexical array in the complex NPdu-guo na-ben shu de haizi(读过那本书的孩子)‘the children, who had read that book’ is more likely to denote a specific person in the context of a covert past tense, which usually involves a bigger context, like this:zuotian wo pengjian-le yixie haizi. Tamen dou du-le Gone with the Wind zhe-ben shu. (Suoyou) duguo zhe-ben shu de haizi zou-le-jinlai…(昨天我碰见了一些孩子。他们都读了 Gone with the Wind 那本书。(所有)读过这本书的孩子走了进来…) ‘Yesterday I met some children. They all had read the bookGone with the Wind. (All) the children, who had read the book, walked in…’ In this context, the head NPhaizi (孩子) ‘children’ is irreducible.So (32) has a nonrestrictive. In this case,na-ben shu(那本书)‘that book’ in (32) cannot be relativized into (33a) as a result of the dissatisfaction of the characterization condition. In(33a), the inner relative clausedu-guo de (读过的)‘who had read (it)’ is just an “orphan”,so the remaining parthaizi zou-le-jinlai de (孩子走了进来的)‘which the children walked into’ cannot characterize the head NPna-ben shu (那本书)‘that book’. Similarly, it is not easy for us to relativizena-ben shu (那本书)‘that book’ in (32) into the recursive (33b)as a result of the dissatisfaction of the aboutness condition.

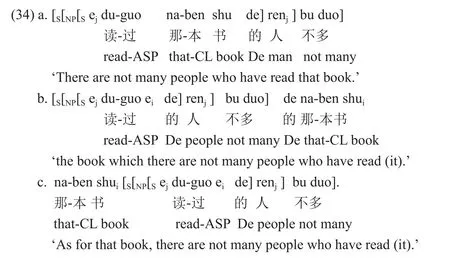

On the other hand, in (34a) the complex NPdu-guo na-ben shu de ren (读过那本书的人)‘the people who have read that book’ denotes some nonspecific persons in the context of the “…bu duo (…不多)” construction. That is to say, the head NPren (人)‘people’ and the context of the “…bu duo (…不多)” construction hint that the head NPren (人)‘people’must be reduced. The reducibility of the head NP of the relative clause only allows for a restrictive. Since the complex NPdu-guo na-ben shu de ren (读过那本书的人)in (34a)has a restrictive,na-ben shu (那本书)‘that book’ in it can be relativized into the recursive complex NP in (34b) for reason of the satisfaction of the characterization condition.Therefore, in (34b), the head NPna-ben shu (那本书)‘that book’ can be characterized by the recursive relative clausedu-guo de ren buduo de (读过的人不多的)‘which there are not many people who have read (it)’. Similarly,na-ben shu (那本书)‘that book’ in (34a)can be topicalized into (34c) for reason of the satisfaction of the aboutness condition.

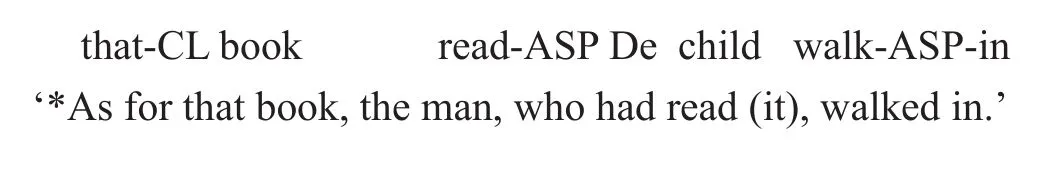

However, although the lexical array in the complex NPdu-guo na-ben shu de haizi(读过那本书的孩子)in the extended expression (35) is still more likely to denote specific persons in the context of covert past tense (similar to (32)), in the bigger context of contrast, the two instances ofhaizimust be reduced by means of restrictive clauses.Since the complex NPs in (35)du-guo na-ben shu de haizi (读过那本书的孩子)andmei du-guo na-ben shu de haizi (没读过那本书的孩子)have restrictives instead of nonrestrictives in them,na-ben shu (那本书)‘the book’ in (35), which is in the acrossthe-board situation, can be relativized into the recursive (36a)/(6a) for reason of the satisfaction of the characterization condition. Similarly,na-ben shu (那本书)‘that book’in (35), which is in the across-the-board situation, can be topicalized into (36b)/(7a) for reason of the satisfaction of the aboutness condition.

More similar examples are shown in (37-39).

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, there are great similarities in acceptability between the above Chinese examples and their corresponding English examples. The similarities lie in the fact that the acceptability-unacceptability contrasts in both Chinese and English recursive complex NPs/the corresponding topic structures can be explained with the characterization/aboutness condition. The acceptability-unacceptability contrasts are in correspondence with the satisfaction-dissatisfaction contrasts of the characterization/aboutness condition,which themselves are in correspondence with the restrictive-nonrestrictive contrasts of the relative clauses, which, in turn, are in correspondence with the reducibility-irreducibility contrasts of the head NPs of the relative clauses.

Chao (1968), Hashimoto (1971), Li (1998), and Huang (1982/1998) maintain that a Chinese relative clause is interpreted as nonrestrictive if it follows a demonstrative, but as restrictive if it precedes it, as shown below.

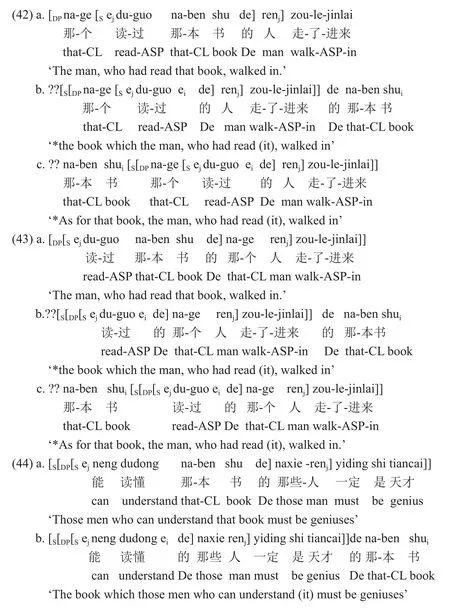

Now I can prove that the linear order cannot decide the restrictive-nonrestrictive distinction of Chinese relative clauses. Let’s see (42-45).

According to the linear order hypothesis in Chao (1968), Hashimoto (1971), and Li(1998), as mentioned above, the relative clause in (42)na-ge du guo (na-ben shu) de ren(那个读过(那本书)的人)‘the man who had read the book’ should be a nonrestrictive,while the relative clause in (43)du-guo (na-ben shu) de na-ge ren‘the man who has read the book’ should be a restrictive. However, if so, according to the Main Clause Hypothesis or the “orphanage” hypothesis, (42a) cannot be converted into (42b-c) while (43a) can be converted into (43b-c). But the fact is that neither the NPna-ben shu‘that book’ in (42a)nor the NPna-ben shu‘that book’ in (43a) can be relativized/topicalized into (42b-c)/(43b-c). Therefore, the relative clause inna-ge du-guo na-ben shu de ren‘the man who has read that book’ in (42a) and the relative clause indu-guo na-ben shu de na-ge ren‘the man who has read that book’ in (43a) should be nonrestrictives. Similarly, according to the linear order hypothesis, the relative clause in (44)neng dudong (na-ben shu) de naxie ren‘those men who can understand that book’ is a restrictive, while the relative clause in (45)naxie neng dudong (na-ben shu) de ren‘those men who can understand that book’ is a nonrestrictive. But the fact is that the NPna-ben shu‘that book’ in both(44a) and (45a) can be relativized/topicalized. Therefore, the relative clauses in both (44a)and (45a) should be restrictives. Therefore, the linear order cannot decide the restrictivenonrestrictive distinction of Chinese relative clauses.

Acknowledgements

This paper was written with support from the National Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of China (Grant No. 15BYY070). I express my appreciation to my teachers,colleagues and friends for their valuable comments on the paper.

Bache, C., & Jakobsen, L. K. (1980). On the distinction between restrictive and nonrestrictive relative clauses in modern English.Lingua, 52, 243-267.

Chao, Y. R. (1968).A grammar of spoken Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Chomsky, N. (1957/2002).Syntactic structures.Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Chomsky, N. (2010). Some simple evo-devo theses: How true might they be for language? In R. K.Larson, V. M. Déprez, & H. Yamakido (Eds.),The evolution of human language(pp. 45-62).New York: Cambridge University Press.

De Vries, M. (2002).The syntax of relativization(Doctoral dissertation). The Netherlands:Netherlands Graduate School of Linguistics.

Demirdache, H. (1991).Resumptive chains in restrictive relatives, appositives and dislocation structures(Doctoral dissertation). Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Fitch, W. T. (2010). Three meanings of “recursion”: Key distinctions for biolinguistics. In R. K.Larson, V. M. Déprez, & H. Yamakido (Eds.),The evolution of human language(pp. 73-90).New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hashimoto, A. Y. (1971). Mandarin syntactic structures.Unicorn,8, 1-149.

Huang, C. R. (1992). Certainty and functional uncertainty.Journal of Chinese Linguistics,20,247-288.

Huang, C.-T. J. (1982/1998).Logical relations in Chinese and the theory of grammar.New York:Garland.

Huddleston, R. (1984).Introduction to the grammar of English. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jackendoff, R. (1972).Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Li, Y.-H. A. (1998). Argument determiner phrases and number phrases.Linguistic Inquiry, 29,693-702.

Lin, J. W. (2003). On restrictive and nonrestrictive relative clauses in Mandarin Chinese.Tsinghua Journal of Chinese Studies,33, 199-240.

Lobina, D. J. (2017).Recursion:A computational investigation into the representation and processing of language.London: Oxford University Press.

Lyons, J. (1977).Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCawley, J. D. (1988).The syntactic phenomenon of English(Vol. 2). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Ross, J. R. (1967).Constraints on variables in syntax(Doctoral dissertation). Cambridge, MA:Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Sells, P. (1985a).Anaphora and the nature of semantic representation. Unpublished manuscript,CSLI, Stanford University, California.

Sells, P. (1985b). Restrictive and non-restrictive modification. CSLI Report. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Xu, L.-J. (2003). 话题句的合格条件 [The licensing condition of topic constructions]. In L.-J.Xu & D.-Q. Liu, (Eds.), 《话题与焦点新论》 [New ideas about topic and focus]. Shanghai:Shanghai Educational Publishing House.

Xu, L.-J. (2006). Topicalization in Asian languages. In M. Everaert & H. van Riemsdijk (Eds.),Blackwelll companion to syntax(pp. 137-174). London: Blackwell.

Xu, L.-J., & Langendoen, D. T. (1985). Topic structures in Chinese.Language, 61, 1-27.

Yang, C.-M. (2013).A study of the syntax and the acquisition of relative structures within the framework of generative grammar.Beijing: The Commercial Press.

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Grammar, Multimodality and the Noun

- The Logic of Legal Narrative1

- An Embodied View of Physical Signs in News Cartoons

- Complementiser and Complement Clause Preference for Verb-Heads in the Written English of Nigerian Undergraduates

- Developing Mathematics Games in Anaang

- Identif i cation by Antithesis and Oppositional Discourse Reproduction in Chinese Space of New Media