NRAS基因突变致系统性红斑狼疮1例并文献复习

2018-01-23李国民刘海梅钱琰琰周利军吴冰冰

李国民 刘海梅 钱琰琰 史 雨 姚 文 张 涛 周利军 徐 虹 吴冰冰 孙 利

1 病例资料

患儿, 男,2014年12月24日出生,2017年8月5日因“反复发热、血小板减少1年”就诊于复旦大学附属儿科医院(我院),以系统性红斑狼疮(SLE)收入院。

患儿1年前发热后出现鼻腔出血,就诊当地医院,血常规PLT 8×109·L-1、凝血功能未见异常。骨髓穿刺提示粒红系增生活跃,巨核细胞45个,颗粒巨核细胞16个,PLT散在可见。诊断“原发性血小板减少性紫癜”,予丙种球蛋白输注及糖皮质激素治疗4 d,外周血PLT计数正常,口服泼尼松1月后停药。6月前至2月前曾发热4次,每次发热4~7 d,外周血PLT计数均正常,体温经治疗后恢复正常。就诊当地儿童专科医院血液科。骨髓穿刺提示红系增生低下,巨核细胞65个。骨髓活检提示髓细胞增生明显活跃,造血容积70%,单核细胞和淋巴细胞多见,粒红系造血受

抑制,幼稚细胞呈现,巨核细胞可见,但有退行性变。继续丙种球蛋白输注及糖皮质激素治疗。10 d前再次发热,血常规Hb 62 g·L-1、PLT 11×109·L-1,C4 0.09 g·L-1,抗核抗体1∶320、抗心磷脂抗体和抗SSA均阳性,血清铁蛋白1 048 ng·mL-1,AST 813 U·L-1。尿常规蛋白2+、RBC193.7个·μL-1,24 h尿蛋白定量180.6 mg。诊断“系统性红斑狼疮(SLE)、巨噬细胞活化综合征”。予甲基泼尼松龙(MP)冲击治疗2个疗程,MP冲击治疗之间及之后予足量MP口服、丙种球蛋白输注、环孢素口服并输注洗涤红细胞和PLT等。经治疗PLT计数稍有改善。为进一步明确病因,来我院就诊。

患儿系G2P2,足月顺产,出生体重2 900 g,出生时无产伤及窒息,既往体健。父亲有高血压病史,母亲体健。父母非近亲联姻。母亲妊娠史2-0-0-2。姐姐16岁,体健。

查体:血压95/65 mmHg,身高88 cm(-1.5 SD),体重12 kg。神志清醒,精神欠佳。面容正常,面部红色斑丘疹,压之褪色。浅表淋巴结无肿大。两肺未闻及干、湿性啰音,心率98·min-1,心律齐,无杂音。腹平软,未及包块,右肋下肝脏3 cm,质软,无压痛,左肋下未及脾脏。左膝关节肿胀,皮温增高,活动受限,有触痛。神经系统未见异常。

入院后多次血常规Hb 68~72 g·L-1、PLT计数(17~33)×109·L-1,尿沉渣蛋白质定性微量至2+、尿蛋白/肌酐0.37、24 h尿蛋白定量186.5 mg,肝、肾功能指标正常,免疫球蛋白IgG 21.4 g·L-1,IgA、IgM和IgE均在正常范围,淋巴细胞亚群绝对计数(个/微升)CD3+995.0(57.3%)、CD3+CD4+628.5(36.2%)、CD3+CD8+349.8(20.1%)、CD19+604.2(34.8%)、CD16+CD56+112.1(6.4%),自身抗体ANA、抗ds-DNA抗体和抗SSA抗体均阳性,直接Coombs试验阳性,补体C4 0.09 g·L-1,C3和CH50均在正常范围。心脏彩超示心脏结构与功能未见异常;腹部B超示右肋下肝脏3 cm、剑突下5 cm,肾、脾均未见异常。

入院后维持SLE诊断,继续泼尼松龙和环孢素A口服治疗,皮疹改善、关节肿痛消失,表1显示实验室指标好转,目前仍在随访中。

表1 先证者实验室相关指标

因患儿起病年龄小,非SLE好发年龄段,经患儿父母知情同意,对患儿及其父母进行家系WES。取患儿和其父母静脉血2 mL,置EDTA抗凝管中混匀。在我院行二代测序,采用我院已建立的WES数据分析流程逐步筛选,发现105个变异位点,根据先证者表型进一步人工筛选到符合先证者主要临床表型及遗传模式的可能致病基因NRAS基因c.38G>A (p.G13D)杂合突变,先证者父母均未携带,为新发突变,见图1。该变异为HGMD数据库已报道的致病性突变。行Sange验证,证实WES的NRAS基因在该家系的测序结果。

图1WES的NRAS基因在该家系的测序结果图

注 Sanger 验证c.38G>A突变,箭头为突变位点

2 文献检索和复习

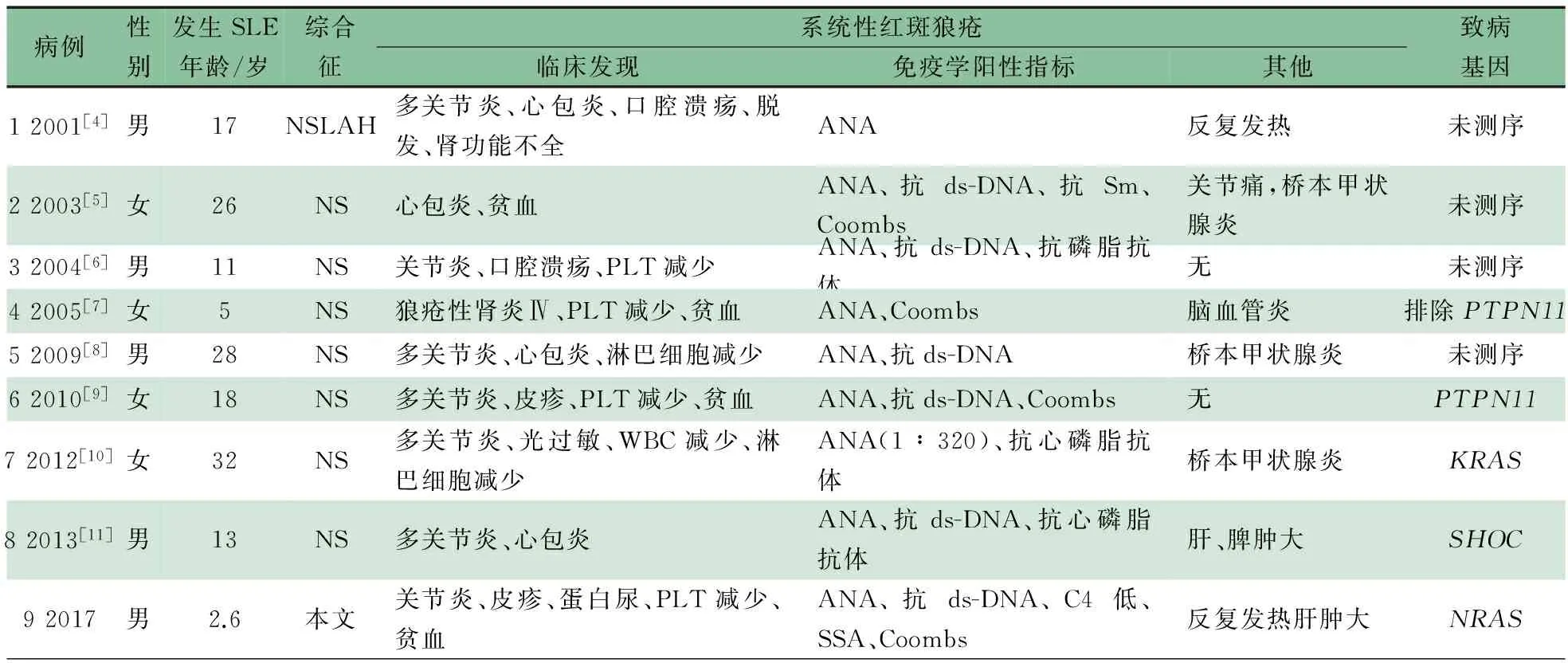

Noonan综合征(NS, OMIM 163950)是RAS病中相对常见的一种[1]。以RAS、自身免疫性疾病、SLE、Noonan综合征为关键词在中国知网、万方、维普和中国生物医学文献数据库中检索;以RASopathies、autoimmune disorders、SLE、Noonan syndrome为关键词检索PubMed和EBSCO数据库。符合RAS病定义及SLE诊断的文献被纳入,RAS病定义和SLE诊断参照相关文献[2, 3]。排除指南、传统综述和动物实验的文献。中文数据库检索到23篇文献报道NS 32例,均无并发自身免疫性疾病或SLE。8篇英文文献符合RAS病并发SLE[4~11],表2显示,男女各4例,诊断SLE的平均年龄16.7岁,7例临床符合NS诊断,1例符合NS相关性疾病。与本文1例合并后共9例,SLE临床指标:7例有单或多关节炎,6例有血液系统受累(主要表现为自身免疫性溶血和PLT下降),4例有心包炎,肾脏受累和口腔溃疡各2例,其他少见表现有皮疹、脱发和光过敏等;免疫学指标:9例均ANA阳性,6例抗ds-DNA阳性,3例抗心磷脂抗体阳性,4例直接Coombs试验阳性。有3例合并桥本甲状腺炎。4例行相关基因检测,3例得到了基因诊断。

表2 9例RAS病并发SLE患者的临床特征

注 NSLAH: NS with loose anagen hair

3 讨论

本文患儿的临床表现及相关实验室检查结果符合SLE诊断。临床指标:①Hb、PLT计数均低于正常值,符合SLE血液系统受累的标准[3];②持续性蛋白尿,尿蛋白/肌酐0.37 (>0.2)mg/mg,24 h尿蛋白定量0.186(>0.150)g,也符合SLE肾脏受累的儿童标准[12];③左膝关节炎。免疫学指标ANA、ds-DNA和抗心磷脂抗体阳性。SLE好发年龄段为青春期,5岁以下SLE十分罕见[11]。本文患儿起病年龄小,诊断SLE时只有2.6岁。SLE是累及多系统的自身免疫性疾病,全基因组关联分析(GWAS)发现SLE存在遗传易感性[13~15]。目前已发现多个易感基因与SLE发病有关,并认为是多基因病[15]。不仅如此,近年发现多个单基因突变均与SLE发病有关,特别是小年龄SLE还可能继发其他遗传性疾病[16, 17]。鉴于此,对本文患儿行家系全外显子测序分析,结果显示NRAS基因c.38G>A (p.G13D)杂合突变,该突变父母均不携带,为新发突变,Sanger法测序验证了该突变。

文献报道,NRAS基因杂合c.38G>A突变可以影响CD95(Fas/APO-1)介导的细胞凋亡,引起自身免疫性淋巴细胞增生综合征(ALPS),其主要临床特征为淋巴细胞增生性表现,如脾脏肿大、自身免疫性疾病,以Coombs阳性溶血性贫血最为常见,免疫性PLT减少次之,还可发生自身免疫性中性粒细胞减少症、肾小球肾炎、多发性神经根炎和皮肤损害(包括荨麻疹和非特异性皮肤血管炎)[18, 19]。NRAS基因杂合突变不仅可以引起ALPS,还可以引起NS[20]。

NRAS基因编码的蛋白是RAS/MAPK信号通路中的信号转导分子之一。RAS/MAPK信号通路可将细胞外生长因子信号传至胞内,对调节细胞周期和细胞的分化、生长、衰老和凋亡起重要作用[1]。约1/3的人类肿瘤与体细胞RAS/MAPK信号通路分子编码基因突变有关,而生殖细胞RAS/MAPK信号通路分子编码基因突变所致的一组遗传异质性疾病称为“RAS病”[1, 21]。表3显示,目前已发现25个RAS/MAPK信号通路分子编码基因突变可导致9种临床综合征[22~43],该组疾病为常染色体显性遗传。NS是相对常见的一种RAS病,已知16个基因突变均可引起该病。约50%的NS由PTPN11基因突变引起[1]。每种RAS病都有其独特的临床表型,但由于每个基因突变都会使RAS/MAPK信号通路调节异常,这些RAS病又有相互重叠的临床表型,如颅面部畸形,心脏畸形,皮肤、肌肉、骨骼和眼部异常,神经认知功能受损,肌张力减退,癌症的风险增高[21]。哺乳动物的RAS基因家族有3个成员,分别是HRAS、KRAS和NRAS,其编码蛋白称为Ras蛋白,是膜结合型的GTP/GDP结合蛋白,在细胞内可传递多种信号。

近年来研究发现,ANA、抗ds-DNA、抗SSA/Ro和抗SSB/La等自身抗体可以在52%的RAS病患者中被检测到,其中约14%的患者符合SLE、抗磷脂综合征和自身免疫性肝炎等疾病诊断,约7%的患者仅有胃、肠和肝脏特异性抗体,无任何临床症状[10]。经文献复习发现,截止目前全球共有8例RAS病并发SLE(“R和S”)报道(见表2)。本例有ANA等多种自身抗体阳性,临床符合SLE诊断,存在新发NRAS基因致病突变,考虑临床特征由NRAS基因突变引起。文献报道8例“R和S”诊断SLE的平均年龄为16.7岁,而本文患儿仅2.6岁;8例“R和S”临床特征均符合NS和NS相关疾病诊断,本文患儿无面容异常,也无其他脏器畸形,临床特征不符合NS诊断,虽然有自身免疫性贫血、PLT下降等,但无脾脏肿大,淋巴细胞亚群分析CD3+绝对计数接近CD4+和CD8+之和(提示无CD4-和CD8-双阴T淋巴细胞增多),故临床上也不符合ALPS;8例“R和S”中,仅4例行相关基因检测,3例分别有PTPN11、KRAS和SHOC基因杂合致病性突变,1例排除PTPN11基因突变。本文患儿发现NRAS基因致病性杂合突变,未发现RAS病的其他基因存在致病性突变。因此,本文患儿基因型和表型均不同于文献报道的“R和S”。由于SLE是环境因素触发有遗传背景的个体所导致的一种自身免疫性疾病,故不排除环境因素如感染可能是造成这种差异的原因。本文患儿每次发生自身免疫性贫血、PLT减少前均有发热,有可能是SLE触发的诱因。

表3 RAS病致病基因

“R和S”:最常见的临床指标是单或多关节炎,其次是血液系统受累,主要表现为自身免疫性溶血和PLT下降,再次是心脏(心包炎)、肾脏受累和口腔溃疡,皮疹、脱发、光过敏等相对少见;常见异常免疫学指标有ANA、抗ds-DNA抗体、抗心磷脂抗体、直接Coombs试验,低补体血症和抗Sm抗体不常见[4~11]。这些“R和S”患儿尚可以合并其他自身免疫性疾病,如桥本甲状腺炎[4~11]。

综上所述,体细胞NRAS基因突变可能与某些肿瘤发病相关,生殖细胞NRAS基因突变所致RAS病可以表现为NS和ALPS。本文1例生殖细胞NRAS基因突变患儿仅有SLE表型,无NS或NS相关综合征表现,进一步丰富了NRAS基因突变表型谱。

[1] Tidyman WE, Rauen KA. Expansion of the RASopathies. Curr Genet Med Rep, 2016, 4(3): 57-64

[2] Rauen KA. The RASopathies. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet, 2013, 14: 355-369

[3] Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum, 2012, 64(8): 2677-2686

[4] Martin DM, Gencyuz CF, Petty EM. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a man with Noonan syndrome. Am J Med Genet, 2001, 102(1): 59-62

[5] Amoroso A, Garzia P, Vadacca M, et al. The unusual association of three autoimmune diseases in a patient with Noonan syndrome. J Adolesc Health, 2003, 32(1): 94-97

[6] Alanay Y, Balci S, Ozen S. Noonan syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus: presentation in childhood. Clin Dysmorphol, 2004, 13(3): 161-163

[7] Lopez-Rangel E, Malleson PN, Lirenman DS, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune disorders in children with Noonan syndrome. Am J Med Genet A, 2005, 139(3): 239-242

[8] Lisbona MP, Moreno M, Orellana C, et al. Noonan syndrome associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus, 18(3): 267-269

[9] Leventopoulos G, Denayer E, Makrythanasis P, et al. Noonan syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus in a patient with a novel KRAS mutation. Clin Exp Rheumatol, 2010, 28(4): 556-557

[10] Quaio CR, Carvalho JF, da Silva CA, et al. Autoimmune disease and multiple autoantibodies in 42 patients with RASopathies. Am J Med Genet A, 2012, 158A(5): 1077-1082

[11] Bader-Meunier B, Cavé H, Jeremiah N, et al. Are RASopathies new monogenic predisposing conditions to the development of systemic lupus erythematosus? Case report and systematic review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum, 2013, 43(2): 217-219

[12] 中华医学会儿科分会肾脏病学组. 狼疮性肾炎诊疗指南. 中华儿科杂志, 2010, 48(9): 687-689

[13] Morris DL, Sheng Y, Zhang Y, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in

Chinese and European individuals identifies ten new loci associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet, 48(8): 940-946

[14] Demirci FY, Wang X, Kelly JA, et al. Identification of a New Susceptibility Locus for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus on Chromosome 12 in Individuals of European Ancestry. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2016, 68(1): 174-183

[15] Ruiz-Larraaga O, Migliorini P, Uribarri M, et al. Genetic association study of systemic lupus erythematosus and disease subphenotypes in European populations. Clin Rheumatol, 2016, 35(5): 1161-1168

[16] Belot A, Cimaz R. Monogenic forms of systemic lupus erythematosus: new insights into SLE pathogenesis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J, 2012, 10(1): 21

[17] 李国民, 刘海梅, 张涛, 等. 赖氨酸尿性蛋白耐受不良1家系(1例合并系统性红斑狼疮)报告并文献复习. 中国循证儿科杂志, 2017, 12(3): 190-195

[18] Munson PJ, Puck JM, Dale J, et al. NRAS mutation causes a human autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2007, 104(21): 8953-8958

[19] Agrebi N, Sfaihi Ben-Mansour L, Medhaffar M, et al. Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome caused by homozygous FAS mutations with normal or residual protein expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2017, 140(1): 298-301

[20] Altmüller F, Lissewski C, Bertola D, et al. Genotype and phenotype spectrum of NRAS germline variants. Eur J Hum Genet, 2017, 25(7): 823-831

[21] Tidyman WE, Rauen KA. Pathogenetics of the RASopathies. Hum Mol Genet, 2016, 25(R2): R123-R132[22] Hamdan FF, Gauthier J, Spiegelman D, et al. Mutations in SYNGAP1 in autosomal nonsyndromic mental retardation. N Engl J Med, 2009, 360(6): 599-uta

[23] Revencu N, Boon LM, Mendola A, et al. RASA1 mutations and associated phenotypes in 68 families with capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation. Hum Mutat, 2013, 34(12): 1632-1641

[24] Niihori T, Aoki Y, Narumi Y N, et al. Germline KRAS and BRAF mutations in cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Nat Genet, 2006, 38(3): 294-296

[25] Cave H. Gene symbol: MAP2K1. Disease: Cardio-Facio-Cutaneous syndrome. Hum Genet, 2008, 123(5): 551

[26] Hanna N, Parfait B. Gene symbol: MAP2K2. Disease: Cardio-Facio-Cutaneous syndrome. Hum Genet, 2008, 123(5): 543

[27] Lorenz S, Petersen C, Kordaβ U, et al. Two cases with severe lethal course of Costello syndrome associated with HRAS p. G12C and p. G12D. Eur J Med Genet, 2012, 55(11): 615-619

[28] Bianchi M, Saletti V, Micheli R, et al. Legius Syndrome: two novel mutations in the SPRED1 gene. Hum Genome Var, 2015, 2: 15051

[29] Pannone L, Bocchinfuso G, Flex E, et al. Structural, Functional, and Clinical Characterization of a Novel PTPN11 Mutation Cluster Underlying Noonan Syndrome. Hum Mutat, 2017, 38(4): 451-459

[30] Carcavilla A, Pinto I, Muoz-Pacheco R, et al. LEOPARD syndrome (PTPN11, T468M) in three boys fulfilling neurofibromatosis type 1 clinical criteria. Eur J Pediatr, 2011, 170(8): 1069-1074

[31] Calcagni G, Baban A, De Luca E, et al. Coronary artery ectasia in Noonan syndrome: Report of an individual with SOS1 mutation and literature review. Am J Med Genet A, 2016, 170(3): 665-669

[32] Luo C, Yang YF, Yin BL, et al. Microduplication of 3p25.2. encompassing RAF1 associated with congenital heart disease suggestive of Noonan syndrome. Am J Med Genet A, 2012, 158A(8): 1918-1923

[33] Kobayashi T, Aoki Y, Niihori T, et al. Molecular and clinical analysis of RAF1 in Noonan syndrome and related disorders: dephosphorylation of serine 259 as the essential mechanism for mutant activation. Hum Mutat, 2010, 31(3): 284-294

[34] Addissie YA, Kotecha U, Hart RA, et al. Craniosynostosis and Noonan syndrome with KRAS mutations: Expanding the phenotype with a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet A, 2015, 167A(11): 2657-2663

[35] Martinelli S, Stellacci E, Pannone L, et al. Molecular Diversity and Associated Phenotypic Spectrum of Germline CBL Mutations. Hum Mutat, 2015, 36(8): 787-796

[36] Flex E, Jaiswal M, Pantaleoni F, et al. Activating mutations in RRAS underlie a phenotype within the RASopathy spectrum and contribute to leukaemogenesis. Hum Mol Genet, 2014, 23(16): 4315-4327

[37] Kouz K, Lissewski C, Spranger S, et al. Genotype and phenotype in patients with Noonan syndrome and a RIT1 mutation. Genet Med, 2016, 18(12): 1226-1234

[38] Chen PC, Yin J, Yu HW, et al. Next-generation sequencing identifies rare variants associated with Noonan syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014, 111(31): 11473-11478

[39] Yamamoto GL, Aguena M, Gos M, et al. Rare variants in SOS2 and LZTR1 are associated with Noonan syndrome. J Med Genet, 2015, 52(6): 413-421

[40] Lee BH, Kim JM, Jin HY, et al. Spectrum of mutations in Noonan syndrome and their correlation with phenotypes. J Pediatr, 2011, 159(6): 1029-1035

[41] Kraft M, Cirstea IC, Voss AK, et al. Disruption of the histone acetyltransferase MYST4 leads to a Noonan syndrome-like phenotype and hyperactivated MAPK signaling in humans and mice. J Clin Invest, 2011, 121(9): 3479-3491

[42] Vissers LE, Bonetti M, Paardekooper J, et al. Heterozygous germline mutations in A2ML1 are associated with a disorder clinically related to Noonan syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet, 2015, 23(3): 317-324