马铃薯食物血糖指数与慢性疾病风险

2018-01-10林金雪娇范志红

林金雪娇 范志红

(中国农业大学食品科学与营养工程学院,北京 100083)

马铃薯食物血糖指数与慢性疾病风险

林金雪娇 范志红

(中国农业大学食品科学与营养工程学院,北京 100083)

马铃薯含有较多淀粉,被西方国家认为是高血糖指数食物。有流行病学研究提示增加马铃薯食物摄入可能影响慢性疾病风险,而这种作用与其提升膳食整体的血糖指数和血糖负荷有关。本文综述了马铃薯与慢性疾病风险的研究证据,以及影响马铃薯血糖指数的品种和烹调加工方法等因素。

马铃薯 血糖指数 淀粉消化 糖尿病

马铃薯(SolanumtuberosumL.),为一年生草本块茎植物,别名土豆、洋芋等。马铃薯块茎淀粉含量丰富,是世界第三大食用作物,最广泛食用的根类蔬菜[1]。2016年,农业部发布《关于马铃薯产业开发的指导意见》,推进马铃薯主粮化[2]。马铃薯富含淀粉,西方膳食中经常食用的马铃薯食物被认为是高血糖指数(glycemic index, GI)食品[3]。然而许多研究表明,马铃薯食物的GI值范围较大,不同品种、烹调方式等均会对马铃薯GI值造成不同的影响。本文归纳了近年来研究中马铃薯与糖尿病风险的研究证据,并对马铃薯食物的GI值及影响因素进行了探讨。

1 马铃薯摄入与慢性疾病风险的流行病学证据

多项研究确认长期摄入高GI食物会增加2型糖尿病、心血管疾病等慢性疾病的发生风险[4-6]。有长期流行病学研究[7-10]显示,摄入过多的马铃薯及其产品可能与慢性疾病风险相关。

瑞典《食品与营养研究杂志》2016年在线发表了一项生态学研究[7],基于FAOSTAT(联合国粮农统计)数据库,比较了42个欧洲国家1993—2008年间5项心血管指标的精确数据,发现与高心血管疾病风险相关的主要因素是能量摄入中来自碳水化合物和酒精的部分,主要源自马铃薯和精制谷物等高GI食物。这能够解释在欧洲地区碳水化合物摄入最高的国家心脑血管疾病(CVD)流行率也最高。然而,该研究没有给出马铃薯和心脑血管疾病相关的直接证据。

Halton等[8]根据Nurse Health Study (NHS)(1980—2000)的食物频次问卷分析马铃薯与糖尿病风险的关系,排除年龄、膳食和非膳食因素的影响后,发现马铃薯和薯条的摄入量与Ⅱ型糖尿病风险有关。按摄入马铃薯或薯条的量进行五分位分组,和摄入量最低组相比,马铃薯摄入最高组的相对风险为1.14;薯条摄入最高组的相对风险为1.21。在肥胖女性中,马铃薯食物促进糖尿病风险的作用更为明显。

Bao等[9]对NHSⅡ(1991—2001)数据进行分析,参与者怀孕前无妊娠糖尿病史以及慢性疾病。在21693位单胎妊娠的女性中,有854例妊娠糖尿病发生。排除年龄、胎次、饮食和非饮食因素,孕前摄入较多马铃薯的女性患妊娠糖尿病的比例更高,较高的马铃薯摄入似乎会增加高风险人群的空腹血糖和胰岛素抵抗。在消除年龄、饮食和非饮食因素的影响后,马铃薯和薯条摄入最高组的女性与最低组相比,患Ⅱ型糖尿病的风险分别增加14%和21%。

基于NHS、NHSⅡ和Health Professional Follow-up Study(HPFS)3项大型流行病学研究的数据,Borgi等[10]对马铃薯摄入与高血压风险进行了前瞻性纵向队列研究,排除其他饮食因素(全谷物、全水果和蔬菜的摄入)影响后,在3项研究当中,烤、煮、捣泥的马铃薯摄入与较高的女性高血压风险均有显著相关。此外,较高的薯条摄入与新增高血压均有显著相关,而油炸土豆片却没有增加风险。

考虑到马铃薯是一种公认的高钾低钠食物,它对高血压的促进作用,很可能是通过促进体重增长而产生效果,而研究确认超重和肥胖会促进高血压的发生[11-12]。作为极受欢迎的大众食材,马铃薯既可以作为蔬菜摄入,也可以作为主食摄入。当马铃薯替代其他蔬菜食用时,必然会增加膳食的总能量摄入,同时提升膳食整体的血糖负荷(glycemic load, GL)值;当马铃薯替代全谷类食物食用时,也会提升膳食的GL值;而高GI和高GL膳食都有促进体重增长的长期效应[13]。研究证实,如用一份马铃薯代替全谷物,则2型糖尿病的相对风险上升30%[5]。对NHS、NHSⅡ和HPFS数据的分析结果[14]也佐证了这个推测:排除基础体重和BMI的影响之后,每增加1份油炸土豆片和马铃薯与4年中的体重增加强烈相关。

2 马铃薯食品的血糖指数

血糖指数的开创者Jenkins等[15]及Soh等[22]的测定将马铃薯归类为高GI食物,因其GI值均高于70。Tahvonen等[21]测定不同烹调和加工方式的马铃薯产品,发现其GI值在73~104之间。但Fernandes等[16]比较了烤土豆、炸薯条、热的和凉的煮土豆,发现GI值变化范围在56~89之间。Henry等[23-26]所测的数值在56~94之间。Atkinson等[17]在研究中指出,马铃薯食物的GI值有很大范围,并认为GI值差异主要来源于烹调加工方式和餐食组成。

在此基础上,King等[18]指出,把马铃薯简单划分为高GI食物可能存在误区,因为其GI值受到烹饪方式的深刻影响。Nayak等[23]更明确提出,马铃薯的餐后血糖反应随品种、成熟度、淀粉结构和加工方式等的变化而变化,改变马铃薯品种的基因型,发展高直链淀粉含量的马铃薯,可以显著降低马铃薯及其产品的GI值;食用冷却后或回热的马铃薯可以降低血糖反应。2016年,Pinhero等[20]对14个品种马铃薯进行比较,测定其总膳食纤维、总淀粉)、快消化淀粉、慢消化淀粉和抗性淀粉(resistant starch, RS),并从体外消化结果计算预期血糖指数(estimated glycemic index, EGI)和预期血糖负荷(estimated glycemic load, EGL),发现品种、处理方式和淀粉组成对EGI有深刻影响,且11种马铃薯被预测为低GL食物。

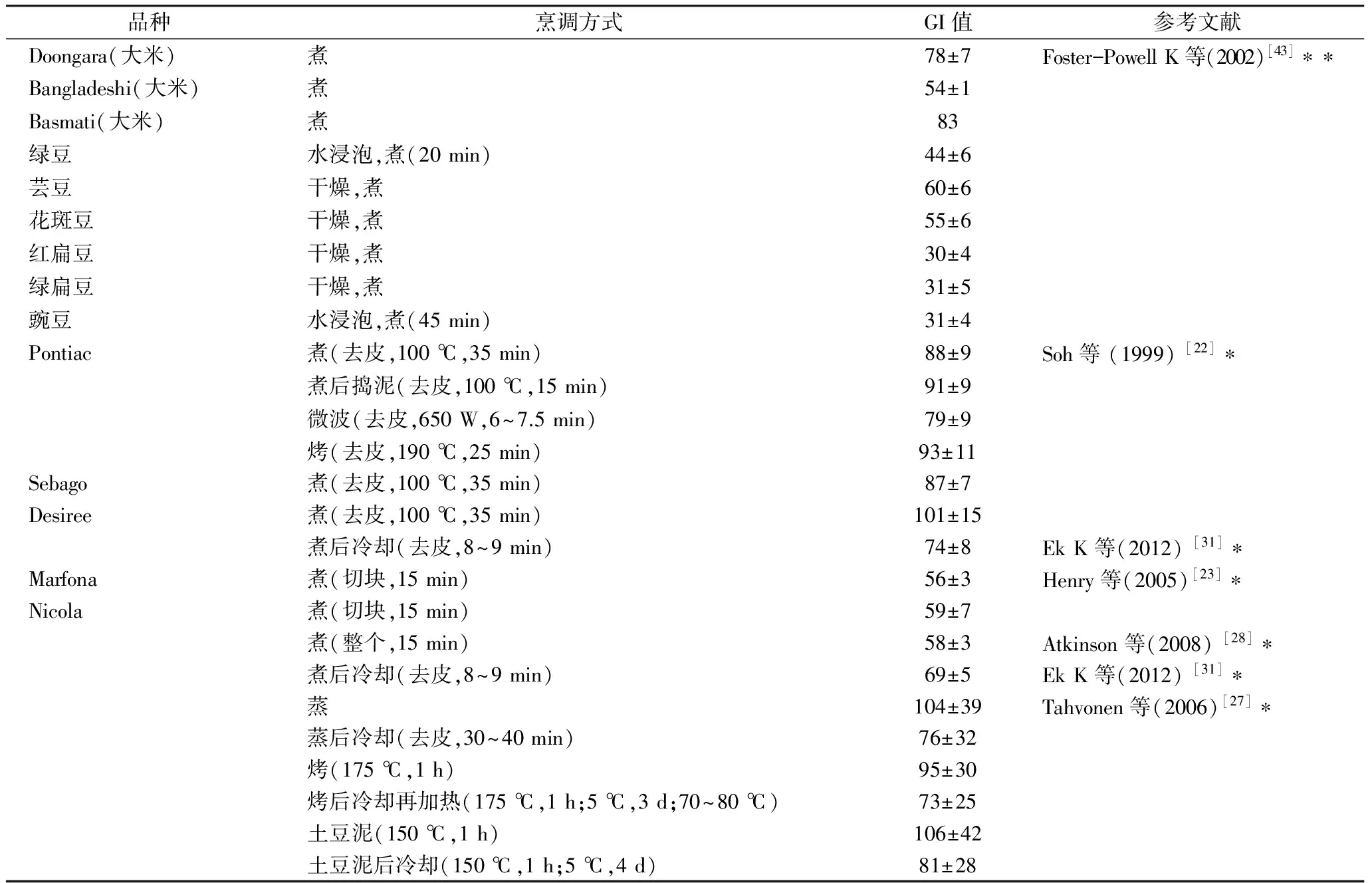

根据文献资料整理了不同品种、烹调方式的马铃薯及部分大米和淀粉豆类GI值(表1)[22-31]。其中,后两者的GI值范围分别在30~60和54~83,具有低GI值的马铃薯作为主食开发具有重要意义。

表1 不同品种、烹调方式的马铃薯GI值

表1(续)

注:*表示以葡萄糖为参比(GI=100),**表示以白面包为参比(GI=100)。

3 影响马铃薯血糖指数数值的因素

从表1可见,马铃薯食物GI文献值范围从53~131,其差异原因主要可归纳为品种因素和烹调处理因素两方面,而前者又涉及淀粉结构差异的影响。

3.1 品种因素

从表1数据可见,Maris Peer 和King Edward两个品种在同样烹调条件下,GI值分别是94和75[24],可见品种差异的影响极大,而品种差异与淀粉类型和结构有关。有研究指出,直链淀粉和支链淀粉的结构对于淀粉消化程度的决定作用[32]。与较低直链淀粉含量的食物相比,高直链淀粉含量的天然淀粉在标准烹调条件下更难膨胀和糊化,消化速度更慢,带来更低的血糖反应和胰岛素反应[33]。

然而,Kai等[31]研究发现,在特定的烹调条件下,相似直链淀粉含量的马铃薯品种在体外消化和体内血糖反应上仍有显著不同。2014年,Kai等[34]对7个品种的马铃薯淀粉特性进行了深入研究,发现具有最低GI值的马铃薯品种Carisma淀粉的糊化特性显著区别于其他品种,它有显著较高的糊化温度、谷值黏度和最终黏度,在烹调中需要更多的热量才开始糊化,具有较好的抗崩解能力,且产生更多黏性的回生淀粉糊,抵抗酶的消化。这提示直链淀粉和支链淀粉的精细结构(如分支点之间的间距)等因素仍需要进一步研究,因为这些差异可能影响到马铃薯烹调过程中糊化、淀粉消化性和GI值。

不同肉色的马铃薯淀粉消化特性也有差异。与白色马铃薯相比,黄色马铃薯的类胡萝卜素含量较高,紫色马铃薯的花青素含量较高。2011年,Nayak等[35]发现马铃薯的总抗氧化能力、总酚和总花青素水平为紫色>红色>黄色>白色的排序。2014年Ramdath等[36]的体内研究发现,紫、红、黄、白4种马铃薯经对流恒温烤箱烹调后,GI值分别为77、78、81和93。研究者认为,有色马铃薯的GI值与其多酚含量高有关,花青素对肠道α-淀粉酶有较强抑制作用。

3.2 烹调处理

马铃薯的西式烹调方法主要是煮、烤、微波、油炸等。通过观察表1,经煮、蒸两种烹调方式处理后的马铃薯具有较高的GI值,而经油炸处理的马铃薯却具有最低的GI值。

煮和蒸2种烹调方式,属于湿热加工,能够为淀粉糊化提供充足的水分。马铃薯煮5 min时,淀粉粒与水亲和,水膨胀并充满细胞;煮10 min后,达到最大膨胀的淀粉粒形成密集群;煮20~30 min后细胞完全分离;煮50 min时细胞结构完全崩解[8]。由于水分充足,马铃薯淀粉颗粒糊化程度较高,因而煮、蒸马铃薯的GI值较高。

烤属于干热烹调,与其他烹调方式相比传热速度较慢。Wilson等[38]在传统烤箱中烤制马铃薯,发现30 min后马铃薯中心温度达到100℃,60 min才达到质地松软的可食状态。在烤的过程中,淀粉的糊化依靠马铃薯本身的水分,升温速率受到表面蒸发冷却的限制,并且表皮对热传导有屏障作用,因此达到糊化的时间较长。微波烹调中,食物中的水分子振动使食物升温,比传统烹调方式热效率更高。Huang等[39]将完整马铃薯置于800 W微波炉中,2~2.5 min后达到65 ℃(分离马铃薯淀粉的糊化温度),4 min后水分快速蒸发,7 min后马铃薯达到食用口感。微波烹调马铃薯时,水分蒸发较快,造成马铃薯质地紧密,糊化程度较低而GI值较小。

马铃薯油炸时,随着温度的升高,马铃薯的水分迅速蒸发使得含水量降低。可能由于水分供应对糊化的限制,和提取出来的淀粉相比,在细胞完整的情况下,马铃薯淀粉粒在油炸时的糊化温度要高6~7 ℃[40]。烹调过程中,油脂被吸入完整马铃薯细胞的内部[41],形成淀粉-脂肪复合物。这能够解释炸薯片具有较低GI值的原因。

一种可以显著改善马铃薯的GI值的方法是冷却。与马铃薯热食相比,在8 ℃放置24 h后GI值降低26%,抗性淀粉含量(占淀粉的比例)从3.3%增加到5.2%[24]。可以推断,冷却导致快消化淀粉转变为慢消化淀粉。另外两项研究也发现,与烹调后热食相比,经冷藏后的马铃薯GI值降低约25%[25-27]。

在烹调马铃薯中添加一定量的醋和橄榄油也有助于降低GI值。与煮马铃薯热食相比,添加以醋和橄榄油为浇汁的烹调冷却后的Sava马铃薯GI值降低了43%[24]。与醋酸类似的添加物,可以通过降低胃排空的速度来降低血糖反应[42],减缓了健康人摄入马铃薯后的急性血糖和胰岛素分泌情况。Henry 等[26]比较不同浇汁对烤马铃薯GI值的影响,发现脂肪的加入使得GI值降低了58%,将马铃薯由高GI值变成低GI值。

4 结论与展望

中国居民膳食指南(2016)中推荐居民每日摄入谷薯类250~400 g,其中包括土豆在内的薯类平均每日摄入50~100 g。西方研究中普遍认为马铃薯是高GI食物,不利慢性疾病预防,但多项研究也表明,马铃薯的GI值因品种和烹调方法而异。我国日常食用的马铃薯品种与洋快餐中的品种有很大区别,烹调方式也不同于西方膳食,在替代部分主食的情况下,对血糖反应和慢病预防会产生何种影响,还需要进行深入研究。在研究数据的基础上,教育国民正确食用马铃薯及其产品,对逐步推进马铃薯作为主粮化产品的政策措施实施极为重要。

[1]Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2008) International year of the potato. http://www.potato2008.org/en/index.html (accessed March 2012)

[2]高雅. 解读《马铃薯产业开发指导意见》16个关键点[J]. 种子科技, 2016, 34(3): 8-9

Gao Y. Interpretation of the 16 key points of potato industry development guidance[J]. Seed Science And Technology, 2016, 34(3): 8-9

[3]曾凡逵, 许丹, 刘刚,等. 马铃薯营养综述[J]. 中国马铃薯, 2015, 29(4): 233-243

Zeng F, Xu D, Liu G, et al. Potato Nutrition: A Critical Review[J]. Chinese Potato Journal, 2015, 29(4): 233-243

[4]Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm E B, et al. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men[J]. New England Journal of Medicine, 2011, 364(25): 2392-2404

[5]Yu D, Zhang X, Shu X O, et al. Dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, and refined carbohydrates are associated with risk of stroke: a prospective cohort study in urban Chinese women.[J]. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2016, 104(5): 1345-1351

[6]Gardner C D, Offringa L C, Hartle J C, et al. Weight loss on low-fat vs. low-carbohydrate diets by insulin resistance status among overweight adults and adults with obesity: A randomized pilot trial[J]. Obesity, 2016, 24(1): 79-86

[7]Grasgruber P, Sebera M, Hrazdira E, et al. Food consumption and the actual statistics of cardiovascular diseases: an epidemiological comparison of 42 European countries[J]. Food and Nutrition Research, 2016, 60(0): 1-27

[8]Halton T L, Willett W C, Liu S, et al. Potato and french fry consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in women[J].American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2006, 83(2): 284-290

[9]Bao W, Tobias D K, Hu F B, et al. Pre-pregnancy potato consumption and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: prospective cohort study[J]. British Journal of Nutrition, 2016, 352: h6898

[10]Borgi L, Rimm E B, Willett W C, et al. Potato intake and incidence of hypertension: results from three prospective US cohort studies[J]. British Journal of Nutrition, 2016, 353: i2351

[11]Must A, Spadano J, Coakley E H, et al. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity[J]. Jama, 1999, 282(16): 1523-1529

[12]Hall J E. The kidney, hypertension, and obesity[J]. Hypertension, 2003, 41(3): 625-633

[13]Breymeyer K L, Lampe J W, Mcgregor B A, et al. Subjective mood and energy levels of healthy weight and overweight/obese healthy adults on high-and low-glycemic load experimental diets[J]. Appetite, 2016, 107(12): 253-259

[14]Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm E B, et al. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men[J]. New England Journal of Medicine, 2011, 364(25): 2392-2404

[15]Jenkins D J, Wolever T M, Taylor R H, et al. Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange[J]. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1981, 34(3): 362-366

[16]Atkinson F S, Foster-Powell K, Brand-Miller J C. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008[J]. Diabetes Care, 2008, 31(12): 2281-2283

[17]Fernandes G, Velangi A, Wolever T M S. Glycemic index of potatoes commonly consumed in North America[J]. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 2005, 105(4): 557-562

[18]King J C, Slavin J L. White potatoes, human health, and dietary guidance[J]. Advances in Nutrition: An International Review Journal, 2013, 4(3): 393S-401S

[19]Nayak B, Berrios J D J, Tang J. Impact of food processing on the glycemic index (GI) of potato products[J]. Food Research International, 2014, 56: 35-46

[20]Pinhero R G, Waduge R N, Liu Q, et al. Evaluation of nutritional profiles of starch and dry matter from early potato varieties and its estimated glycemic impact[J]. Food Chemistry, 2016, 203(14): 356-366

[21]Thed S T, Phillips R D. Changes of dietary fiber and starch composition of processed potato products during domestic cooking[J]. Food Chemistry, 1995, 52(3): 301-304

[22]Soh N L, Brand M J. The glycaemic index of potatoes: the effect of variety, cooking method and maturity[J]. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1999, 53(4): 249-254

[23]Henry C J, Lightowler H J, Strik C M, et al. Glycaemic index values for commercially available potatoes in Great Britain[J]. British Journal of Nutrition, 2006, 94(6): 917-921

[24]Leeman M, Ostman E, Björck I. Vinegar dressing and cold storage of potatoes lowers postprandial glycaemic and insulinaemic responses in healthy subjects[J]. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2005, 59(11): 1266-1271

[25]Fernandes G, Velangi A, Wolever T M. Glycemic index of potatoes commonly consumed in North America[J]. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 2005, 105(4):557-562

[26]Henry C J K, Lightowler H J, Kendall F L, et al. The impact of the addition of toppings fillings on the glycaemic response to commonly consumed carbohydrate foods[J]. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2006, 60(6): 763-769

[27]Tahvonen R, Hietanen R M, Sihvonen J, et al. Influence of different processing methods on the glycemic index of potato (Nicola)[J]. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 2006, 19(4): 372-378

[28]Atkinson F S, Foster-Powell K, Brand-Miller J C. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008[J]. Diabetes Care, 2008, 31(12): 2281-2283

[29]Leeman M, Ostman E, Björck I. Glycaemic and satiating properties of potato products[J]. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2007, 62(1): 87-95

[30]中国疾病预防控制中心营养与食品安全所. 中国食物成分表[M]. 北京:北京大学医学出版社, 2009

Institute of nutrition and food safety; Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Chinese food composition[M]. Beijing Peking University Medical Press, 2009

[31]Ek K L, Wang S, Copeland L, et al. Discovery of a low-glycaemic index potato and relationship with starch digestion in vitro[J]. British Journal of Nutrition, 2013, 111(4):1-7

[32]Syahariza Z A, Sar S, Hasjim J, et al. The importance of amylose and amylopectin fine structures for starch digestibility in cooked rice grains[J]. Food Chemistry, 2013, 136(2): 742-749

[33]Goddard M S, Young G, Marcus R. The effect of amylose content on insulin and glucose responses to ingested rice[J]. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1984, 39(39): 388-392

[34]Lin E K, Wang S, Brand M J, et al. Properties of starch from potatoes differing in glycemic index[J]. Food and Function, 2014, 5(10): 2509-2515

[35]Nayak B, Berrios J D J, Powers J R, et al. Colored potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) Dried for antioxidant-rich value-added foods[J]. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 2011, 35(5): 571-580

[36]Ramdath D D, Padhi E, Hawke A, et al. The glycemic index of pigmented potatoes is related to their polyphenol content[J]. Food and Function, 2014, 5(5): 909-915

[37]Thybo A K, Martens H J, Lyshede O B. Texture and microstructure of steam cooked, vacuum packed potatoes[J]. Journal of Food Science, 1998, 63(4): 692-695

[38]Wilson W D, MacKinnon I M, Jarvis M C. Transfer of heat and moisture during oven baking of potatoes[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2002, 82(9): 1074-1079

[39]Huang J, Hess W M, Weber D J, et al. Scanning electron microscopy: tissue characteristics and starch granule variations of potatoes after microwave and conductive heating[J]. Food Structure, 1990, 9(2): 113-122

[40]Aguilera J M, Cadoche L, López C, et al. Microstructural changes of potato cells and starch granules heated in oil[J]. Food Research International, 2001, 34(10): 939-947

[41]Bouchon P, Aguilera J M. Microstructural analysis of frying potatoes[J]. International journal of food science and technology, 2001, 36(6): 669-676

[42]Liljeberg, H., & Bjorck, I. Delayed gastric emptying rate may explain improved glycaemia in healthy subjects to a starchy meal with added vinegar[J]. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition,1998, 52(5): 368-371

[43]Foster-Powell K, Atkinson F S, Brand-Miller J C. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2002[J]. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2002, 76: 5-65.

The Glycemic Indexes of Potatoes Products and Chronic Diseases Rais

Lin Jinxuejiao Fan Zhihong

(College of Food Science and Nutritional Engineering,China Agricultural University,Beijing 100083)

Potato products were generally characterized as high glycemic food for they were starchy foods. Some epidemiological studies suggested that high potato food intake might raise the risk of obesity and some chronic diseases by raising the glycemic index and glycemic load of daily diet. This review summarized the possible association between potato food intake and chronic diseases, as well as the possible variety factors and preparation treatments which may affect the glycemic indexes of potato foods.

potatoes,glycemic indexstarch digestion,diabetes

TS215

A

1003-0174(2017)12-0025-06

2017-01-04

林金雪娇,女,1994年出生,硕士,食物营养

范志红,女,1966年出生,副教授,食物营养