Unplanned hospitalizations for metastatic cancers: The changing patterns ofinpatient palliative care, discharge to hospice care,and in-hospital mortality in the United States

2017-11-07JasonSalemiCharlesChimaKiaraSpoonerRogerZoorob

Jason L. Salemi, Charles C. Chima, Kiara K. Spooner, Roger J. Zoorob

Unplanned hospitalizations for metastatic cancers: The changing patterns ofinpatient palliative care, discharge to hospice care,and in-hospital mortality in the United States

Jason L. Salemi1, Charles C. Chima1, Kiara K. Spooner1, Roger J. Zoorob1

Objective:To describe the rates and temporal trends ofinpatient end-of-life care among patients hospitalized with metastatic cancer in the United States.

Methods:We used data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample to conduct a cross-sectional analysis of unplanned inpatient hospitalizations of patients aged 18 years or older with metastatic cancer from 2002 to 2011. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess patient-and hospitallevel predictors of discharge to hospice care, palliative care, and in-hospital mortality. Temporal trends in outcomes were characterized with use of joinpoint regression.

Results:There were an estimated 350,241 unplanned hospitalizations per year of patients with a diagnosis of metastatic cancer. During their inpatient stay, 5.8% of patients received palliative care, and among those discharged alive, 12.2% were referred to hospice care. The rate ofinpatient palliative care increased from 2.3% to 13.6%, the rate of discharge to hospice care increased from 4.1% to 15.6%, and the in-hospital mortality rate decreased from more than 14.0% to 9.8%. These patterns were consistent across cancer subtypes, and were most pronounced among patients with extreme risk of mortality.

Conclusion:Despite increases in the provision of comfort-oriented care to patients with metastatic cancer, few receive such services. We recommend screening protocols in hospitals to identify patients who are good candidates for palliative care consultation and hospice referral.

End-of-life; hospice care; inpatient mortality; metastatic cancer; palliative care;unplanned hospitalization

Introduction

Despite improvements in treatment and survival, cancer remains the second leading cause of death in the United States, behind only heart disease [1, 2]. Cancer is already the leading cause of death in several US states and among some racial/ethnic groups [2], and accounts for nearly one in every four deaths [1]. Furthermore,relative to heart disease, which tends to kill the very old, cancer, specifically among women,predominantly kills the middle-aged [3].Patients with terminal cancer often undergo intensive treatment, with more than 60%experiencing hospitalization in the last month of life [4]. Intensive treatment at the end of life, when comfort-oriented care is preferred by patients and their families, has been recognized as one of the major forms of overtreatment that contributes substantially to the billions of dollars in wasteful healthcare spending each year in the United States [5]. Moreover, aggressive and unnecessary care at the end of life is often not congruent with patient preferences or health-related quality of life [6—8]. Thus for patients with advanced cancer, in addition to early initiation of palliative care services, timey hospice referral is likely to improve patient satisfaction at the end of life and reduce healthcare costs. A lesser-known issue concerns the most appropriate time to initiate such interventions at a population level.

Although cancer patients, particularly those with advanced stages of disease, experience frequent interactions with the healthcare system at the end of life, end-of-life discussions are typically not initiated in time [9, 10]. Hence such encounters constitute missed opportunities for more appropriate services for end-stage cancer, including palliative care and hospice care. With their fi nding that an unscheduled hospitalization for a patient with metastatic cancer is a marker of death in the near term, Rocque et al. [11] provided insights into issues surrounding ‘trigger events’ and the appropriate time to initiate end-of-life discussions. They recommended that any patient with metastatic cancer who experiences an unscheduled hospitalization, given the diminished chances of survival following discharge, should be considered hospice eligible and suitable for end-of-life planning. Therefore an unplanned hospitalization episode in a patient with advanced metastatic cancer can be viewed as an easily identifi able event that could become a screening and intervention point for improving end-of-life care in cancer patients.

At the national level in the United States, few data exist regarding temporal trends in the provision of palliative care and hospice referral services in patients with advanced cancer,except for one study assessing these end-of-life care options among patients with metastatic ovarian cancer [12] and another assessing discharge to hospice care among patients with metastatic prostate cancer [13]. We examined cancers in the United States with the 10 highest age-adjusted death rates across both sexes; these were responsible for 70% of the estimated 580,350 US cancer deaths in 2013 [1]. The primary aims of this study were to (1) assess trends in inpatient palliative care, in-hospital mortality, and discharge to hospice care among patients hospitalized with an advanced stage (i.e.,metastasis) of any of the top 10 most deadly cancers in the period from 2002 to 2011; (2) estimate changes in these trends over time with use of joinpoint regression; and (3) identify patient- and hospital-level predictors of discharge to hospice care, palliative care, and in-hospital mortality.

Methods

Study design and data sources

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional analysis ofinpatient hospitalizations in the United States between January 1,2002, and December 31, 2011, using data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s (HCUP’s) Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). The NIS represents the largest all-payer, publicly available inpatient database in the United States. To create the nationally representative database each year, all nonfederal community hospitals from participating states (1049 hospitals from 46 states in 2011) are classifi ed into strata based on fi ve hospital-level characteristics: geographic region of the United States, urban/rural location, number of beds, type of ownership, and teaching status. By means of a systematic random sampling process, 20% of hospitals are selected from each stratum, and all inpatient hospitalization records from selected hospitals constitute the annual NIS database. To facilitate use of the NIS to generate national frequency and prevalence estimates, HCUP calculates sampling weights from this two-stage clustered design and provides them with each annual database.

Study population

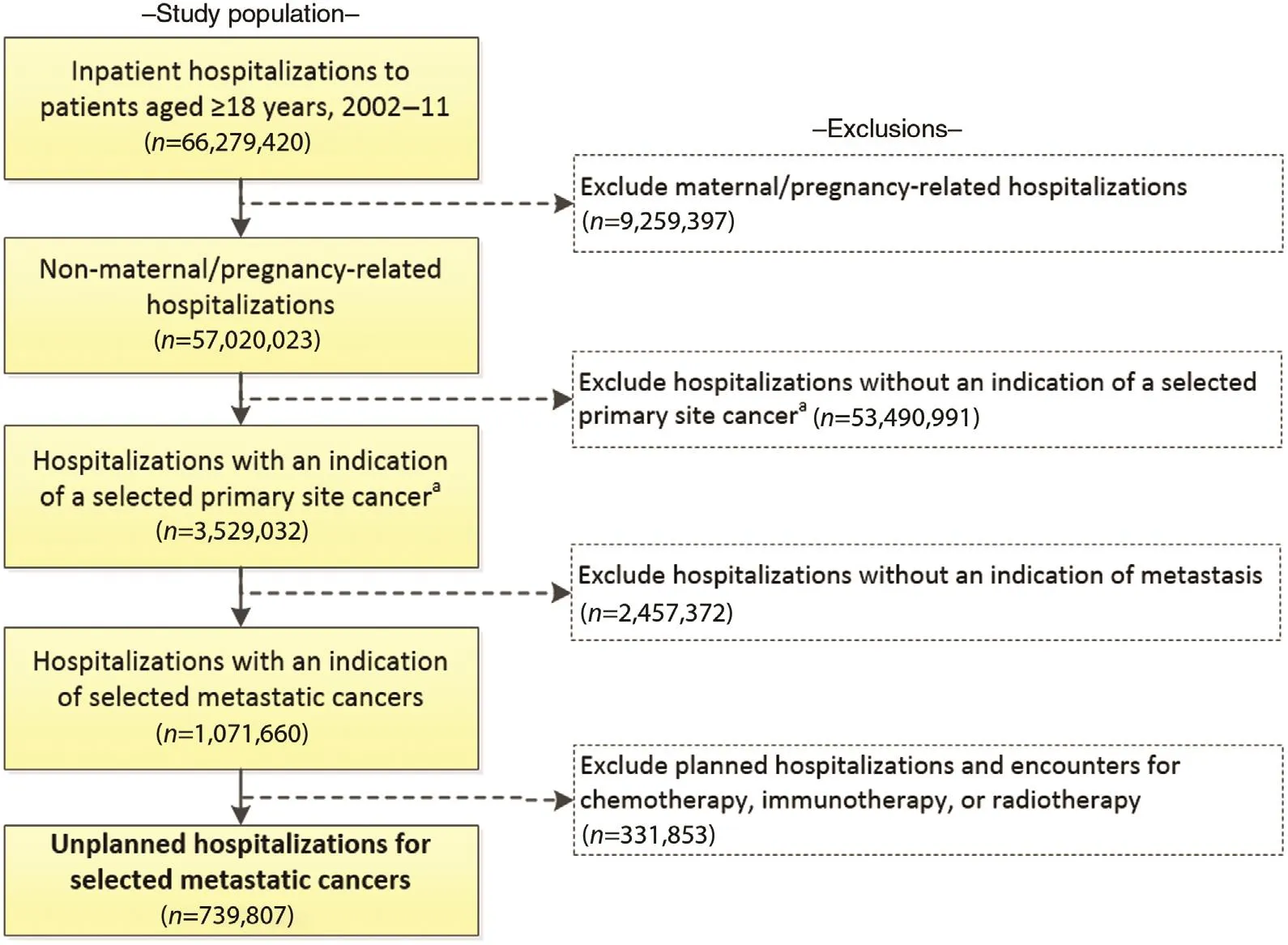

Our target population consisted of patients aged 18 years or older who were hospitalized with metastatic cancer in the United States between January 1, 2002, and December 31,2011. We restricted our analysis to primary site cancers with the 10 highest age-adjusted cancer death rates in the United States, which we ascertained from the US cancer statistics produced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Cancer Institute [14]. Using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes, we selected hospitalizations for patients with a diagnosis of one or more of the following primary site cancers: lung (162.2—162.9, 209.2, 231.2);colorectal (153.0—153.9, 154.0, 154.1, 154.8, 230.3, 230.4);female breast (174.0—174.9, 233.0); prostate (185.0, 233.4);pancreatic (157.0—157.9); ovarian (183.0); liver (155.0—155.2,230.8); uterine (179, 182.0—182.8, 233.2); non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (200.0—200.9, 202.0-202.3, 202.7-203.0); leukemia (202.4—202.5, 203.1—203.1, 204.0—204.9, 205.0—205.9,206.0—206.9, 207.0—207.8, 208.0—208.9). We then used the presence of additional diagnosis codes for secondary malignant neoplasms (196.0—198.9) to restrict our analysis to hospitalizations for metastatic cancer. Although rare, we excluded hospitalization records, regardless of the presence of metastatic cancer, in which the primary reason for admission was associated with pregnancy or childbirth. Last, since this study focused on end-of-life care, we excluded those hospitalizations that were elective (i.e., planned), including those in which the primary purpose was the administration of chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or radiotherapy (Fig. 1).

End-of-life care outcomes

We examined the prevalence and temporal trends of three clinical outcomes associated with end-of-life care: receipt ofinpatient palliative care services, in-hospital mortality, and discharge to hospice care for those that survive the hospitalization episode. Discharge to hospice care was defi ned with use of the “discharge disposition” documented on the hospitalization record, and constituted both hospice care to be received at home and hospice care to be provided by a certifi ed medical facility. Receipt ofinpatient palliative care was identifi ed by means of the presence of the V66.7 ICD-9-CM code as a principal or secondary diagnosis. Last, in-hospital mortality was defi ned as death before hospital discharge and operationalized as a discharge disposition of “expired.” For patients who were discharged alive, we were unable to assess any posthospitalization events (e.g., subsequent receipt of hospice care, palliative care, or mortality) following discharge because of the cross-sectional nature of the dataset.

Fig. 1. Determination of a nationally representative sample of unplanned hospitalizations of patients with a diagnosis of selected metastatic cancer aged 18 years or older, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, United States, 2002—2011. The frequencies presented are the raw (unweighted) number ofinpatient hospitalizations. When weighted, the fi nal analytic population of 739,807 represents 3,502,408 hospitalizations in the United States.

Patient- and hospital-level covariates

For each inpatient hospitalization, the NIS database captures various sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Patient age was categorized as 18—39 years, and then in 10-year strata for ages 40 years and older (e.g., 40—49 years, 50—59 years).Self-reported race/ethnicity, which is reported differently across states, was standardized by fi rst grouping this as Hispanic or non-Hispanic, and then further classifying the non-Hispanics by race (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or non-Hispanic other). Insurance status was based on the primary payer for the hospitalization, and was classifi ed as Medicare,Medicaid, private, uninsured (self-pay or no charge), and other.Socioeconomic status was estimated from the median household income in the patient’s zip code of residence, and estimated values were grouped into quartiles. Clinical factors included the timing of hospital admission (weekday vs. weekend), the primary cancer site, the site of metastasis, the patient’s chronic disease burden, and the estimated risk of mortality while hospitalized. To assess the chronic disease burden, we used HCUP’s Chronic Condition Indicator software [15] to classify each patient’s diagnosis as chronic or not chronic and, if chronic, to determine the specific body system(s) affected. We then created a variable to indicate the number of different body systems impacted by chronic conditions (zero or one, two or three, four or fi ve, or six or more systems). The inpatient risk of mortality was fi rst based on the diagnosis-related group to which a patient was assigned on the basis of age, sex, comorbidities, and diagnoses and procedures received during the stay. Then, with use of a proprietary algorithm developed by 3MTMHealth Information Systems [16], these were ‘severity-adjusted’ into all-patient refi ned diagnosis-related groups, and the risk of mortality was categorized as minor, moderate, major, or extreme.

We also considered several characteristics of the treating hospital that are captured within the NIS databases, including US census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), hospital size based on the number short-term acute beds in a hospital (small, medium, and large), and location/teaching status(urban—teaching, urban—nonteaching, and rural).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the distribution of patient and hospital characteristics among unplanned hospitalizations of patients with a diagnosis of one or more of the selected metastatic cancers. We calculated the frequency and rate of discharge to hospice care, provision ofinpatient palliative care services, and in-hospital mortality, overall and within each population subgroup. We also assessed the most common primary reasons for hospitalization among patients with metastatic cancer and described the variation in rates of each outcome across principal diagnoses. Although the denominator for determining the rate of palliative care and in-hospital mortality consisted of the entire study population, the rate of discharge to hospice care was assessed only among patients who survived their inpatient stay, since discharge to hospice care was not possible among those who died before discharge. All hospitalizations were weighted to account for the NIS sampling design and so that national estimates could be generated.

Simple and multivariable survey logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confi dence intervals (CIs) that represent the association between each outcome and each patient- and hospital-level covariate. For each outcome, we constructed a crude (unadjusted) model and three multivariable models. The fi rst multivariable model included all sociodemographic variables (age, race/ethnicity, household income, and primary payer). The second model added patientlevel clinical factors such as weekday versus weekend admission, primary cancer site, site of metastasis, chronic disease burden, and the risk of mortality. The third (fully adjusted)model added all hospital-level factors. We present adjusted measures of association for only the fully adjusted model since they represent the best statistical fi t to the data.

Joinpoint regression was used to estimate and describe temporal trends in discharge to hospice care, palliative care, and in-hospital mortality during the 10-year study period. Joinpoint regression is designed to identify and describe changes in the rate of events over time [17]. First, joinpoint regression assumes that a single trend best describes outcome rates over time;therefore it fi ts the data to a straight line (one with no joinpoints). A joinpoint is then added to the model, and a Monte Carlo permutation test is used to determine whether the model fi t is improved. This process of adding joinpoints continues iteratively until an optimal number of joinpoints is identifi ed.Each joinpoint ref l ects a statistically significant change in the temporal trend, and the model estimates the annual percent change (APC) to describe how the rate changes within each distinct time interval [18]. HCUP-provided trends fi les were used to account for a changing NIS sampling design during the study period and to ensure consistency of sampling weights and study variables over time [19]. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA),and Joinpoint, version 4.2.0.2 [17]. Because of the deidentifi ed,publicly available nature of NIS data, the analyses performed for this study were considered exempt by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Results

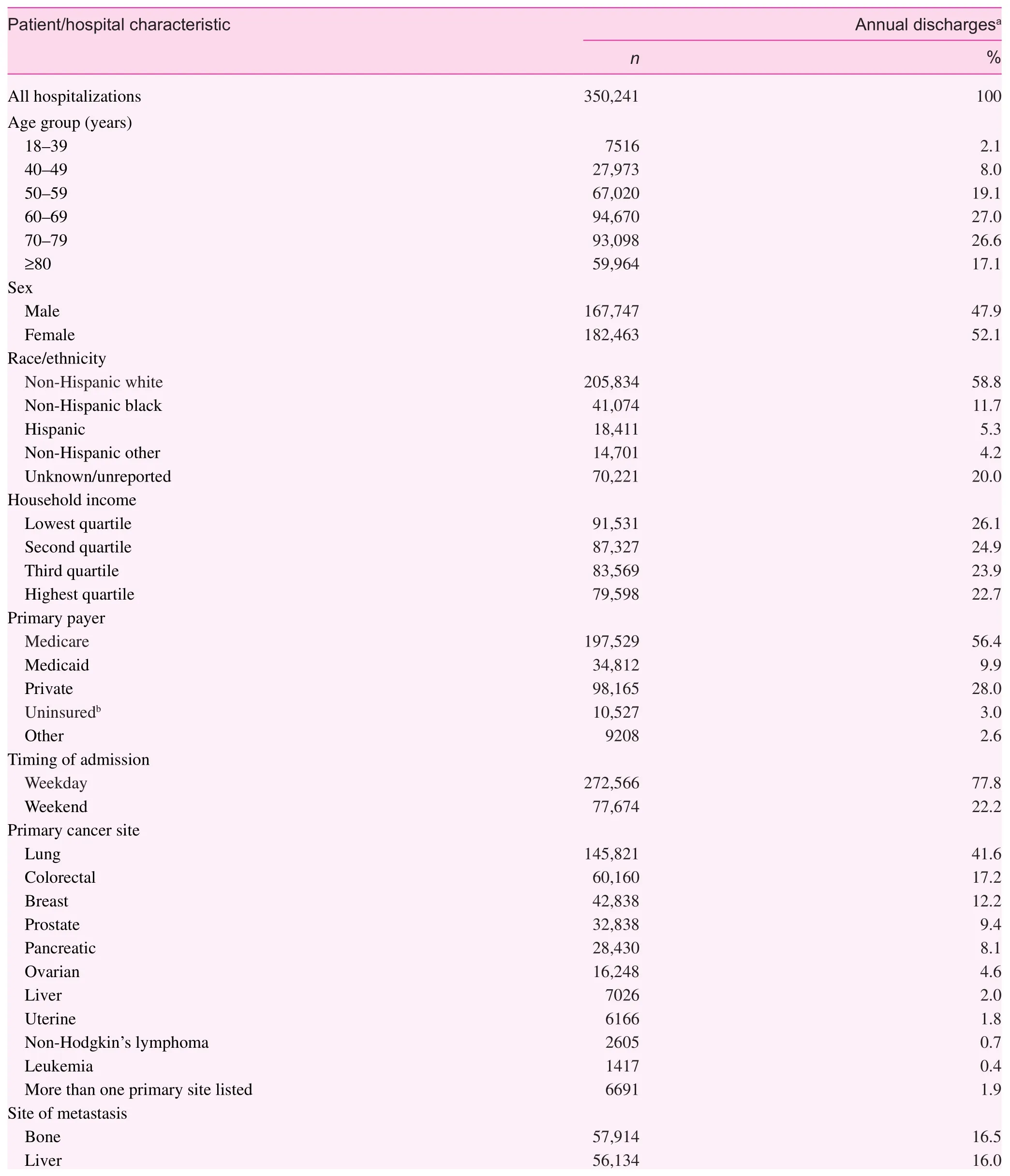

Following all exclusions, we identifi ed 739,807 unplanned hospitalizations of nonpregnant patients aged 18 years or older with a diagnosis of one or more of the primary site cancers included in this study and in which metastasis had occurred(Fig. 1). When the data were weighted to ref l ect the sampling design, this translated into more than 3.5 million hospitalizations in the United States during the 10-year study period. More than 70.0% of the study sample were aged 60 years or older,with slightly more women than men (Table 1). Among those with a self-reported race/ethnicity, nearly three-quarters were non-Hispanic white, 15.0% were non-Hispanic black, and 7.0%were Hispanic. Most of the patients had Medicare coverage(56.0%), followed by private insurance (28.0%) and Medicaid coverage (10.0%). Only 3.0% of patients were uninsured. The most common primary site cancers were lung (41.6%), colon/rectum (17.2%), and breast (12.2%), and the most common sites of metastasis were bone and the liver. However, 3 in 10 patients experienced metastasis to more than one site.

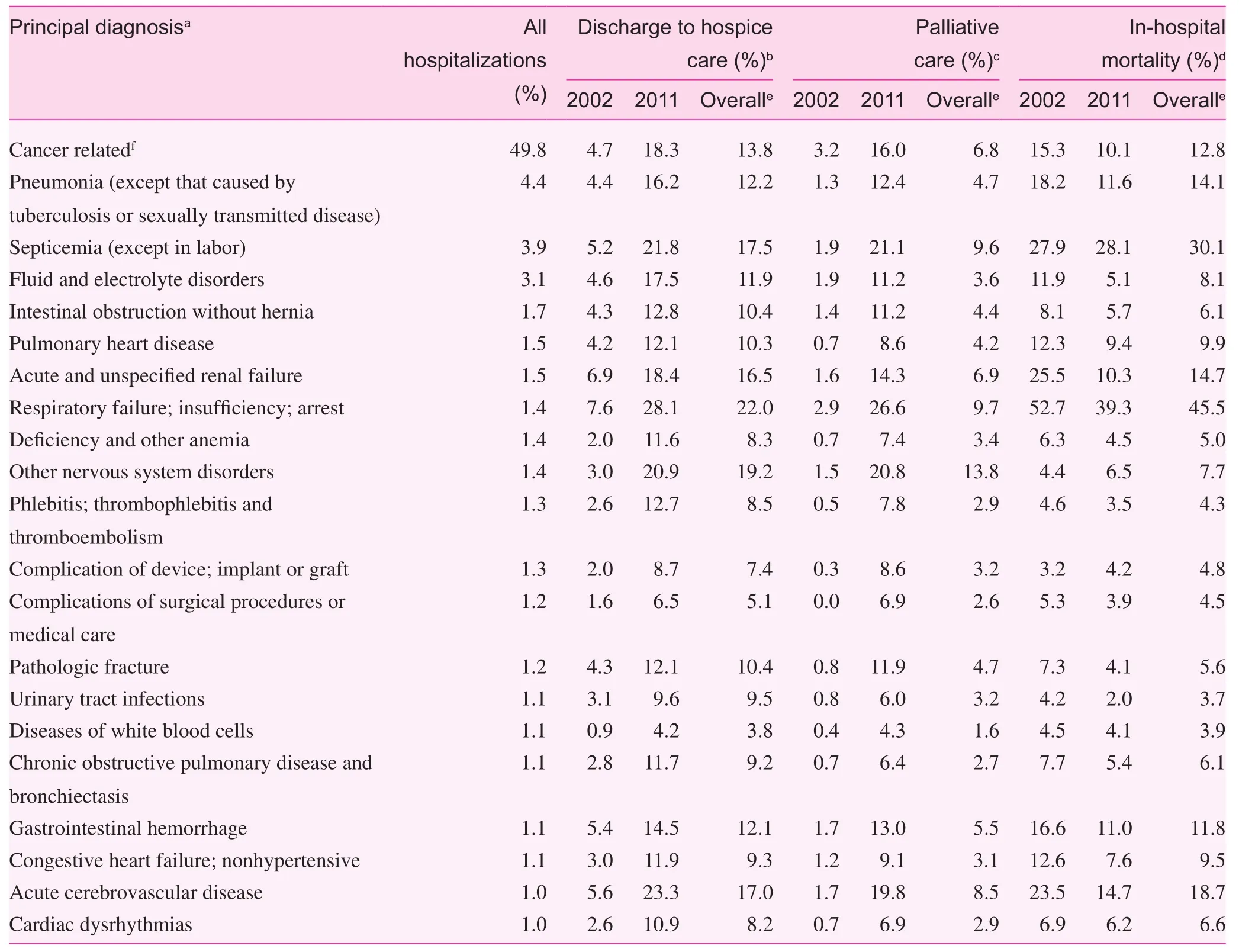

The most common reasons for these unplanned hospitalizations, aside from the cancer diagnosis, were pneumonia (4.4%),septicemia (3.9%), and fl uid and electrolyte disorders (3.1%;Table 2). Because of their metastatic cancer, 62.0% of patients were estimated to have a major or extreme risk of mortality, and 12.0% actually died before discharge; however, we observed substantial variation in mortality and other outcome rates on the basis of the primary reason for hospitalization. For nearly every condition, there was an increase in the rate of both discharge to hospice care and inpatient palliative care, and a decrease in in-hospital mortality between 2002 and 2011.

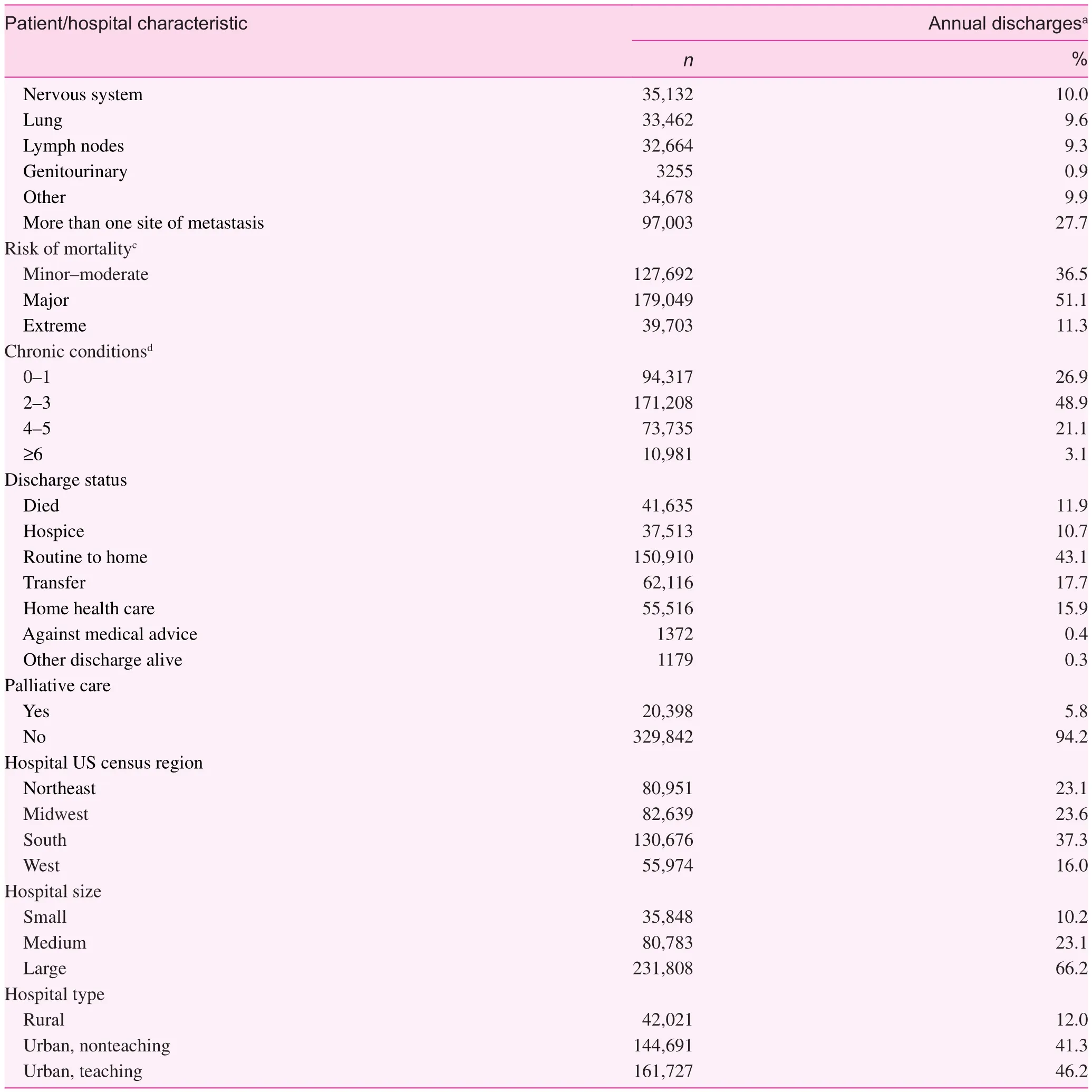

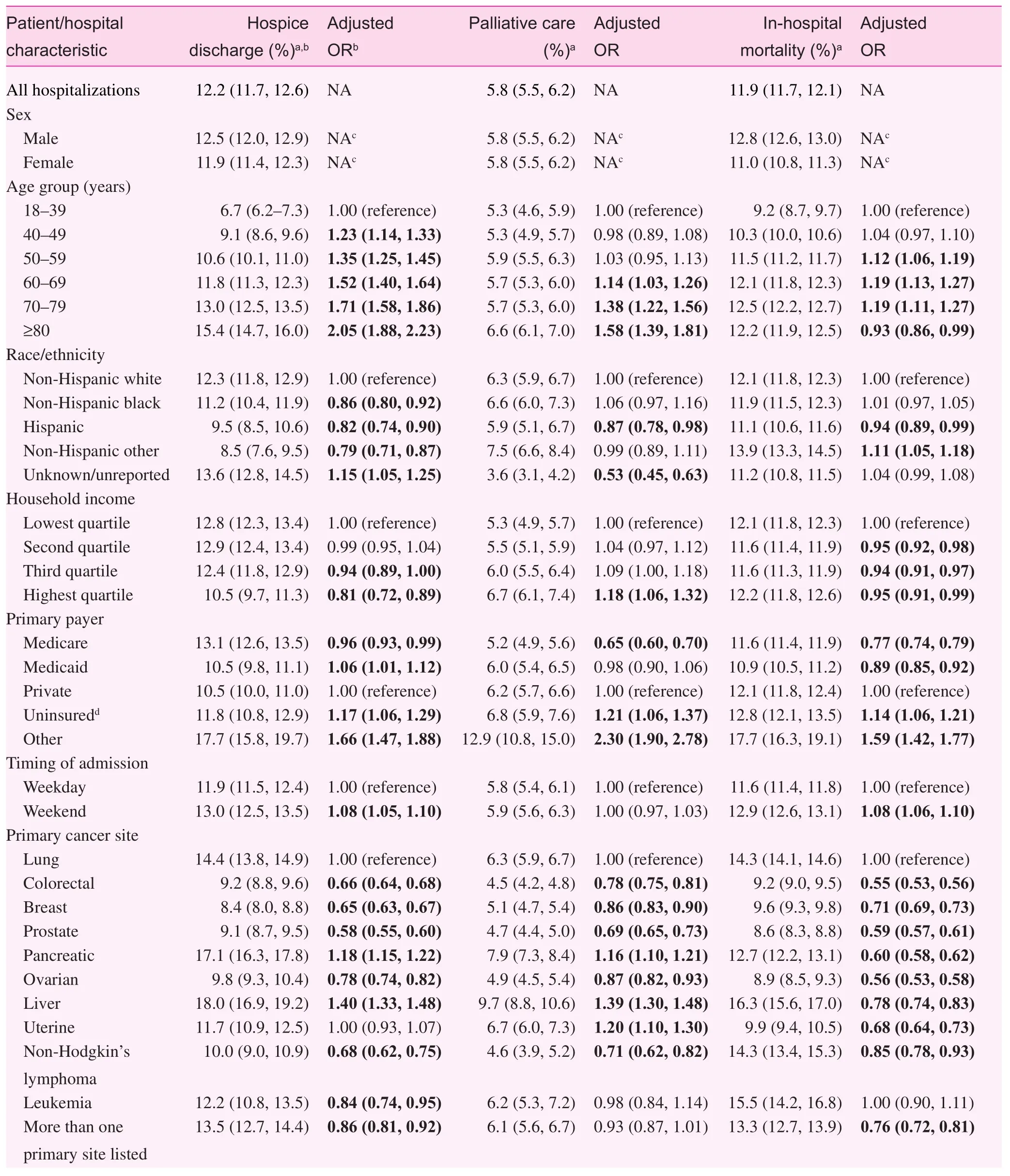

During their inpatient stay, 5.8% of patients received palliative care services, and among those who were discharged alive,12.2% were discharged to hospice care at home (7.4%) or at a certifi ed medical facility (4.8%). Table 3 presents the crude rates and adjusted ORs of predictors of discharge to hospice care, palliative care, and in-hospital mortality among the study population. Increasing patient age tended to be associated with increased odds of both palliative care and discharge to hospice care. Compared with patients younger than 40 years, those aged 80 years or older were 58.0% more likely to receive palliative care (OR 1.58; 95% CI 1.39—1.81) and twice as likely to be discharged to hospice care (OR 2.05; 95% CI 1.88—2.23). Hispanics had between 12.0% and 17.0% lower odds of receiving inpatient palliative care than other race/ethnic groups, and Hispanics,non-Hispanic blacks, and other non-Hispanics were respectively 18.0%, 14.0%, and 21.0% less likely than non-Hispanic whites to be discharged to hospice care. Uninsured patients were approximately 20.0% more likely both to receive palliative care and to be discharged to hospice care than patients with private insurance, and patients living in areas with the highest (vs. lowest) median household income had 18.0% increased odds of receiving palliative care, but 19.0% decreased odds of being discharged to hospice care. As expected, even after adjustment for age and other factors, the type of cancer, site(s)of metastasis, and estimated risk of mortality were predictive of each outcome. The highest odds of palliative care and discharge to hospice care were among patients with liver cancer,and those with metastasis to more than one site of the body.Compared with patients with a minor to moderate risk of mortality, those with an extreme risk of mortality were 2.60 (95%CI 2.38—2.75) and 3.30 (95% CI 3.15—3.43) times more likely to receive palliative care and be discharged to hospice care respectively. We also observed differences across hospital-level characteristics. The highest odds ofinpatient palliative care were among hospitals in the West and Midwest, large hospitals,and urban teaching hospitals. Conversely, hospitals in the South and urban nonteaching hospitals had the highest odds of discharge to hospice care. Small, rural hospitals consistently had the lowest likelihood of palliative care and discharge to hospice care, and the highest odds ofin-hospital mortality.

Table 1. Distribution of selected patient sociodemographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics among unplanned hospitalizations of patients with a diagnosis of selected metastatic cancer aged 18 years or older, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, United States, 2002—2011.

Table 1 (continued)

Table 2. Outcomes for primary reason for hospitalization among unplanned hospitalizations of patients with a diagnosis of selected metastatic cancer aged 18 years or older, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, United States, 2002—2011.

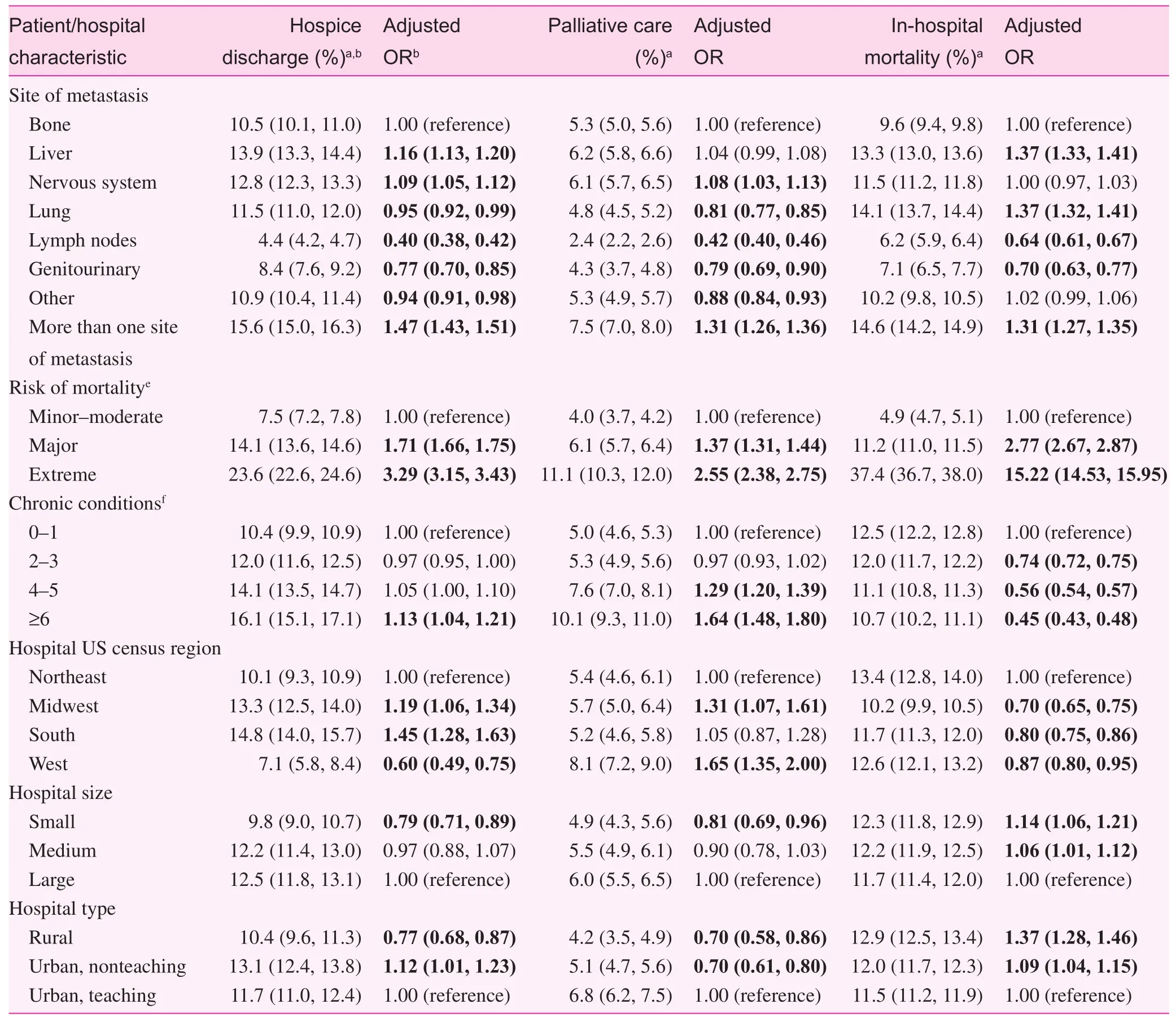

We observed considerable changes in the patterns of palliative care, discharge to hospice care, and in-hospital mortality during the study period (Fig. 2A). The overall rate ofinpatient palliative care increased from 2.3% in 2002 to 13.6% in 2011, translating into a 28.0% annual increase (APC 27.8, 95% CI 21.1—35.0).Temporal trends in palliative care were consistent across cancer subtypes, as ref l ected by the low variability in estimated APCs when data were stratifi ed by primary cancer site (Fig. 2B). The

rate of discharge to hospice care increased sharply between 2002 and 2004 (APC 55.1; 95% CI 16.1—107.1), more than doubling in 3 years. The rate of discharge to hospice care continued to increase at more than 8% annually between 2004 and 2008 (APC 8.5; 95%CI 0.8—16.9), but this was followed by a plateauing between 2008 and 2011. Although there was more variability in actual rates of discharge to hospice care across cancer subtypes, the patterns of change over time were remarkably consistent. Contrary to hospice and palliative care, in-hospital mortality decreased consistently throughout the study period at nearly 4.0% each year, from more than 14.0% in 2002 to 9.8% in 2011. The decline in mortality was not due to a change in the distribution of cancer subtypes over time as evidenced by the statistically significant decreases in every primary cancer site except for leukemia, the least prevalent subtype in the study (data not shown).

Table 3. Crude rates and adjusted odds ratios assessing predictors of discharge to hospice care, palliative care, and in-hospital mortality among unplanned hospitalizations of patients with a diagnosis of selected metastatic cancer aged 18 years or older, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, United States, 2002—2011.

Table 3 (continued)

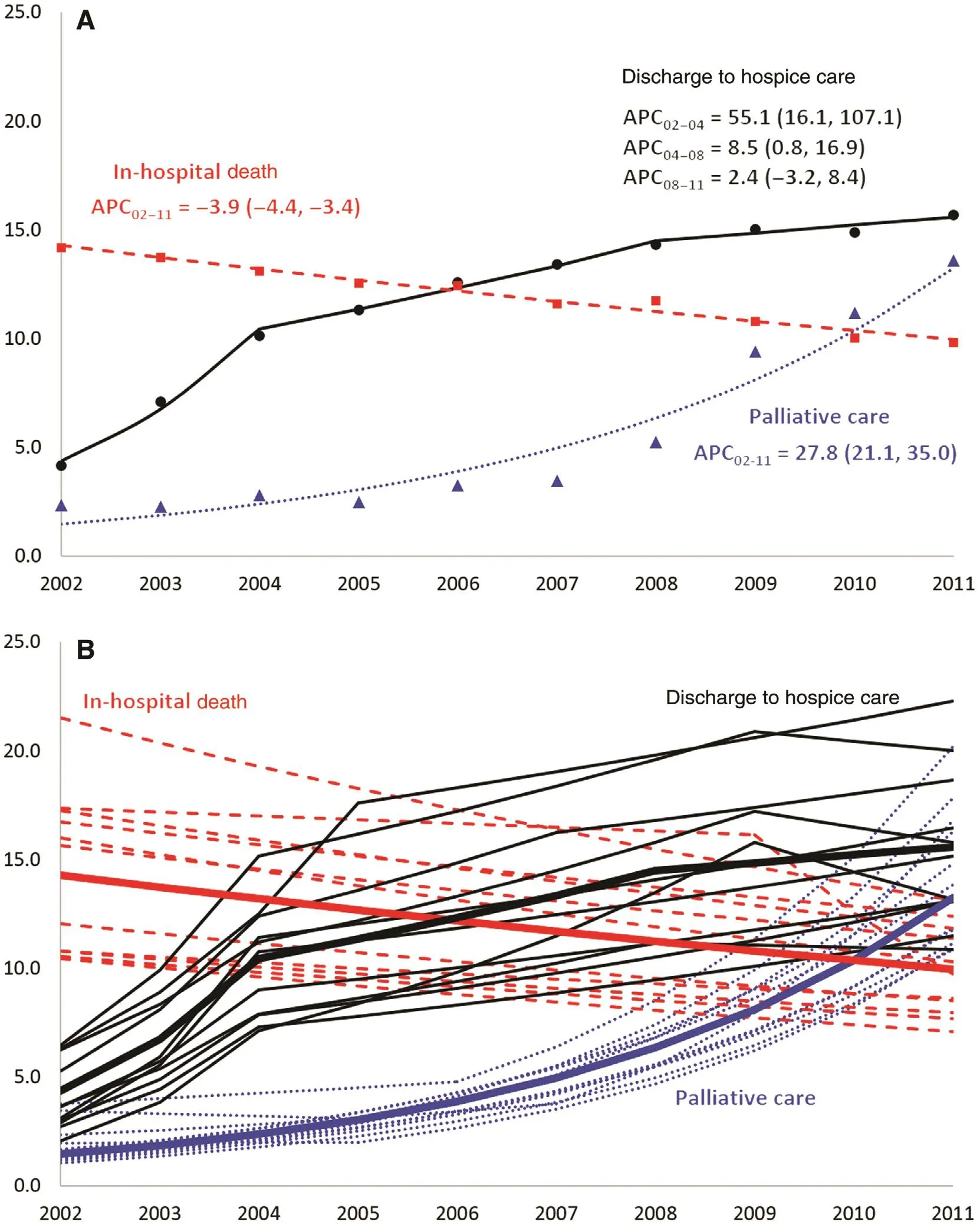

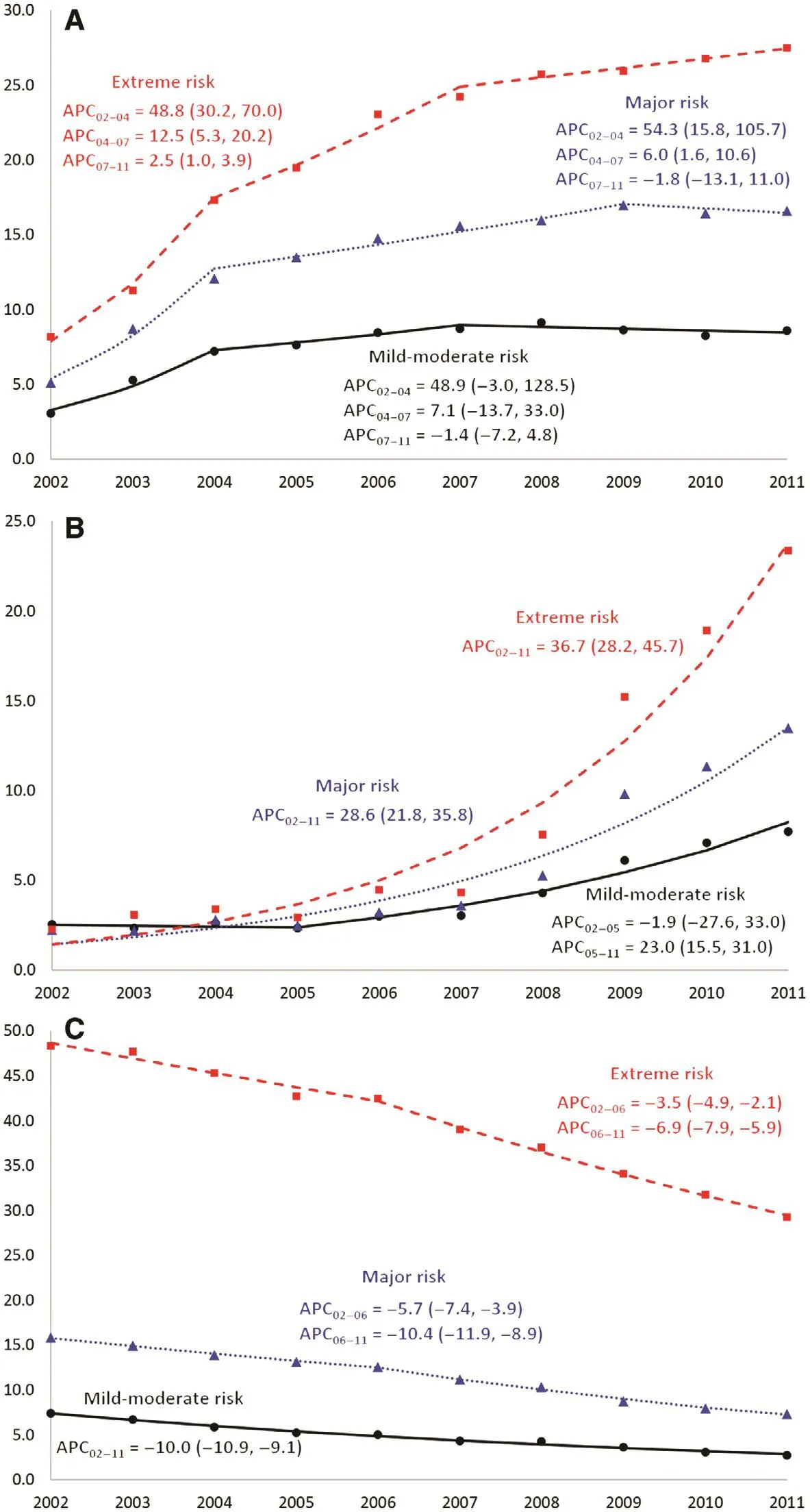

The strongest determinant of each clinical outcome—discharge to hospice care, palliative care, and mortality before discharge—was disease severity as approximated by the estimated risk ofinpatient mortality. Although the pattern of change in each outcome was fairly consistent when stratifi ed by risk subgroups; the most pronounced increases in the rate of hospice and palliative care were observed among patients with the severest cases of metastatic cancer (Fig. 3A, B). Between 2002 and 2011, patients with metastatic cancer who were classifi ed as having an ‘extreme’ risk of death experienced an increase in the rates of discharge to hospice care from 7.5% to 27.0%, and a 13-fold increase in receipt ofinpatient palliative care from 1.8%to 23.5%. Collectively, these patients also experienced a 3.5%annual decrease in mortality from 2002 to 2006, followed by a steeper 7% decline from 2006 to 2011 (Fig. 3C). Whereas nearly half of all extreme-risk patients died before discharge in 2002,7 in 10 were being discharged alive by 2011. Even patients with‘mild to moderate’ or ‘major’ risk of death experienced marked declines in inpatient mortality during the 10-year study period.

Discussion

We found low average levels of provision of comfort-oriented care services—documented inpatient palliative care (5.8%) and discharge to hospice care (12.2%)—among a nationally representative population of US metastatic cancer patients with an unplanned hospitalization. Despite evidence that this population has a high risk of death in the near term [11], most of them are not being given alternatives to intensive care at the end of life. This is consistent with prior fi ndings that US patients often receive aggressive care at the end of life [20]. Considering that less than half of terminally ill patients will initiate end-of-life care discussions by themselves [21], providers should be more proactive in recognizing clinical triggers that warrant the initiation of alternative end-of-life care discussions.

Although the overall levels remained low, there were considerable increases in the rates of provision of palliative care services (from 2.3% to 13.2%) and discharge to hospice care (from 4.1% to 15.6%) over the study period. Whereas palliative care had a steady and pronounced annual increase of 28.0%, the rate of discharge to hospice care went from an initial period of rapid increase to a much slower growth phase and fi nally ended in a plateau phase. Hence the trends of provision of comfort-oriented care to patients with metastatic cancer are generally headed in a direction consistent with recent care recommendations; however,the relative stagnation in the rates of discharge to hospice care during the last 3 years of the study period warrants attention.

On average about 12.0% of the patient population died during the hospitalization, but the inpatient mortality rate decreased at a steady pace from a rate of 14.0% in 2002 to less than 10.0% in 2011. In addition to increased use of hospice care at home and at hospice facilities, the decrease in mortality could be, in part, a ref l ection ofimprovements in the quality ofinpatient care for patients with metastatic cancer over time;however, these improvements do not speak to patient survival following hospital discharge. Still, metastatic cancer patients who died in the hospital without hospice use represent missed opportunities for better end-of-life care.

It is remarkable to note that although there is some variation in the three outcomes by cancer type, less for palliative care than for discharge to hospice care and in-hospital mortality, the trends were considerable in magnitude and consistently in the same direction. As noted earlier, the cancers included in this study collectively constitute most of the burden of cancer deaths in the United Sates and provide meaningful insights into the changing patterns of cancer care. It is therefore prudent to act on these fi ndings without the need for further single cancer site studies of alternative care practices.

Fig. 2. Temporal trends in discharge to hospice care, palliative care, and in-hospital mortality among unplanned hospitalizations of patients with a diagnosis of selected metastatic cancer aged 18 years or older, Nationwide Inpatient Sample, United States, 2002—2011.

Fig. 3. Temporal trends in (A) discharge to hospice care, (B) palliative care, and (C) in-hospital mortality among unplanned hospitalizations of patients with a diagnosis of selected metastatic cancer aged 18 years or older stratifi ed by the risk of mortality, Nationwide Inpatient Sample,United States, 2002—2011. The x-axis represents the year of discharge and the y-axis represents the percentage ofinpatient discharges with the outcome ofinterest. Lines represent the trend estimated by joinpoint regression. Markers represent the observed annual data points. APC, annual percent change, expressed as a point estimate, with the 95% confi dence limits in parentheses.

As expected, the strongest predictor affecting the likelihood of each study outcome was the inpatient risk of mortality categorization, a proxy for the overall severity of the patient’s illness. Nearly two of every fi ve people classifi ed as having an extreme risk of death ended up dying during that hospitalization episode, with an odds of dying that was 15 times higher than that for those considered to be at minor to moderate risk,even after adjustment for potential confounders. This extreme risk group also had about three times increased odds of receiving inpatient palliative care services and, if they survived the hospitalization, of being discharged to hospice care. Our fi ndings are encouraging as one would expect that patients with advanced disease and a higher likelihood of death should be prioritized for comfort-oriented care. Furthermore, not only were these patients with extreme risk of mortality more likely to get appropriate end-of-life care, the trends showed that the rate of provision of such care services to them increased at a faster rate over time. So they are not just being appropriately prioritized for comfort- oriented care relative to patients with less severe disease, but this prioritization has improved over time. Notwithstanding, 40.0% of patients classifi ed as having major or extreme risk of mortality were discharged routinely to their home. This again points to a low penetration of hospice care among cancer patients nearing the end of their lives.

There were socioeconomic disparities across the study outcomes. Other racial/ethnic groups were generally less likely than non-Hispanic whites to receive inpatient palliative care and to be discharged to hospice care. Unsurprisingly, older age was associated with increased odds of each of the three outcomes. Younger people are more likely to want to cling on to life even when their disease has advanced significantly, and are thus going to be more likely to exhaust all intensive treatment options and be less disposed to comfort care. Income and healthcare insurance had mixed effects: people living in more aff l uent neighborhoods were more likely to receive palliative care but less likely to die during hospitalization and to be discharged to hospice care. People with Medicare coverage were not only the least likely to die but were also the least likely to receive palliative care and be discharged to hospice care. This is consistent with earlier fi ndings that Medicare patients receive very high intensity care at the end of life [20]. In fact, more than one of every four Medicare dollars is spent in the last 1 year of life ofits beneficiaries, and in a given year Medicare spends,on a per capita basis, six times the amount of money on new decedents as compared with surviving beneficiaries [22]. Thus,addressing aggressive care at the end of life will likely result in huge savings for the Medicare program.

Lastly, the size and type of the hospital of care had a significant impact on the outcomes. Patients admitted to smaller and rural hospitals were more likely to die during their hospitalization and were less likely to receive palliative care and to be discharged to hospice care. This is likely as a result of fewer resources at the disposal of these hospitals. Even though palliative medicine was recognized as a subspecialty of general medicine in the United Kingdom as far back as 1987, palliative care specialization among physicians in the United States became established only in 2008 [23]. Hence, being a relatively recent fi eld, the availability of such specialists in rural areas will lag that of urban areas. Even in urban areas, as we observed, this disparity remains as teaching hospitals are more likely to offer inpatient palliative care than their nonteaching counterparts. Interestingly, however, urban teaching hospitals were less likely than nonteaching hospitals to discharge patients to hospice care. We hypothesize that this is likely due to a higher inclination for intensive care at teaching hospitals; since teaching hospitals are often regarded as centers of excellence in various aspects of clinical care, they might be more inclined to exhaust all measures to keep patients alive even when their illness may have progressed beyond the point of curability or of salvaging an acceptable quality of remaining life.

Our fi ndings should be considered in the light of several limitations. First, we sought to focus on patients with advanced stages of cancer, but since the NIS does not have information on cancer staging, we relied on the best available proxy of disease progression—the presence of metastasis. Furthermore, the defi -nition of our study population and subsequent analyses depend largely on the ability ofiCD-9-CM codes in the NIS to accurately and completely capture the primary cancer site and presence of metastatic disease. These rely on documentation in the medical record, translation of the condition into an appropriate diagnostic code, and entry into the electronic discharge record, all of which are subject to human error. However, the accuracy and positive predictive value of administrative datasets such as those of the NIS specifically to capture metastatic disease are quite good and have been estimated to be in the 75% to 95% range [24, 25].Second, we could not extend the assessment of trends beyond 2011 because as from 2012 discharge to hospice care is no longer coded as a destination for hospital discharge in the NIS. Third,our reliance on the V66.7 ICD-9-CM code restricts our assessment to documented inpatient palliative care, which is dependent on the quality of reporting and a potentially subjective and variable defi nition of what constitutes palliative care. On the basis of studies that have reported suboptimal sensitivity of the V66.7 code [26, 27], we anticipate underestimation of all possible palliative care interactions that might have occurred during inpatient care. Furthermore, factors such as improved insurance coverage for palliative care and the introduction of board certification to hospice and palliative medicine in the middle of the fi rst decade of this century [12] may have incentivized or enhanced reporting,thereby explaining some of the increased trend for palliative care observed in this study. These biases are less likely to affect the other two outcomes—inpatient mortality and discharge to hospice care—since they do not rely on ICD-9-CM codes. However, as noted earlier, because of the cross-sectional nature of the NIS, we cannot tell if or when patients discharged to hospice care eventually enrolled in hospice care or received hospice services.

Despite these limitations, the NIS is the largest all-payer,publicly available inpatient database in the United States; therefore a major strength of this study is its use of a large nationally representative sample of hospitalizations to measure important dimensions of end-of-life cancer care. Hence the fi ndings can be extrapolated to the general population of the United States with metastatic cancer. A unique strength of this particular study is that instead of focusing on single cancer sites [12, 13], we assessed outcomes for multiple cancers that collectively represent most of the cancer death burden in the United States. Also, other related national studies in the United States focused on inpatient palliative care alone and did not assess temporal trends [28, 29]. This study expands on previous research by using joinpoint regression to assess changes in outcome trends over time instead of relying on a potentially faulty assumption that a single trend represents the changing practice patterns for end-of-life care in the United States.

Conclusion

This study set out to characterize predictors and assess trends in inpatient mortality and the provision of palliative and hospice services to metastatic cancer patients who experience unplanned hospitalization. Unplanned hospitalization in this population has been shown to be an indication ofincreased risk of death in the short term, thereby warranting consideration of alternatives to intensive and potentially invasive end-of-life care when such a trigger event is experienced. We found that over the 10-year period from 2002 to 2011, even though there were rapid increases in the provision ofinpatient palliative care services and discharge to hospice care among these patients, only a minority of patients received these services. These fi ndings suggest a continuation of aggressive care even as patients near the end of life. We recommend screening protocols in hospitals to identify cancer patients who are likely to benefi t from palliative care and those who will be good candidates for hospice referrals. Such screening is likely to improve the chance that end-of-life discussions are initiated at a time that offers patients the opportunity to receive more appropriate and less expensive care, thereby improving satisfaction, enhancing quality of life,and reducing unnecessary healthcare costs.

Conflict ofinterest

The authors declare no conflict ofinterest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or from non-profi t sectors.

1. American Cancer Society. [Internet] Cancer facts & fi gures 2013,2013. [accessed 2016 Nov 7]. Available from: www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-036845.pdf.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Internet] Changes in the leading cause of death: recent patterns in heart disease and cancer mortality. NCHS data brief no. 254, 2016. [accessed 2016 Nov 17].Available from: www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db254.htm.

3. Pathak EB. Is heart disease or cancer the leading cause of death in United States women? Womens Health Issues 2016;26(6):589—94.

4. Dartmouth Atlas. [Internet] Percent of cancer patients hospitalized during the last month of life, 2012. [accessed 2016 Nov 16]. Available from: www.dartmouthatlas.org/data/table.aspx?ind=178.

5. Lallemand N. [Internet] Health policy brief: reducing waste in health care. Health Affairs, 2012. [accessed 2016 Nov 20].Available from: www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=82.

6. Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, Gallagher PM, Skinner JS, Bynum JP, et al. Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences? A study of the US Medicare population. Med Care 2007;45(5):386—93.

7. Higginson IJ, Sen-Gupta GJ. Place of care in advanced cancer:a qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences.J Palliat Med 2000;3(3): 287—300.

8. Pritchard RS, Fisher ES, Teno JM, Sharp SM, Reding DJ, Knaus WA, et al. Inf l uence of patient preferences and local health system characteristics on the place of death. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46(10):1242—50.

9. Lopez-Acevedo M, Havrilesky LJ, Broadwater G, Kamal AH,Abernethy AP, Berchuck A, et al. Timing of end-of-life care discussion with performance on end-of-life quality indicators in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2013;130(1):156—61.

10. Mack JW, Cronin A, Taback N, Huskamp HA, Keating NL, Malin JL, et al. End-of-life care discussions among patients with advanced cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2012;156(3):204—10.

11. Rocque GB, Barnett AE, Illig LC, Eickhoff JC, Bailey HH, Campbell TC, et al. Inpatient hospitalization of oncology patients: are we missing an opportunity for end-of-life care? J Oncol Pract 2013;9(1):51—4.

12. Uppal S, Rice LW, Beniwal A, Spencer RJ. Trends in hospice discharge, documented inpatient palliative care services and inpatient mortality in ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2016;143(2):371—8.

13. Sammon JD, McKay RR, Kim SP, Sood A, Sukumar S, Hayn MH,et al. Burden of hospital admissions and utilization of hospice care in metastatic prostate cancer patients. Urology 2015;85(2):343—9.

14. US Cancer Statistics Working Group. [Internet] United States cancer statistics: 1999—2013 incidence and mortality Web-based report.Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute,2016. [accessed 2016 Oct 25]. Available from: www.cdc.gov/uscs.

15. Health Care Cost and Utilization Project. [Internet] Chronic condition indicator (CCI) for ICD-9-CM, 2015. [accessed 2016 Apr 15]. Available from: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp.

16. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Internet] Mortality measurement: development of the 3M™ all patient refi ned diag,2009. [accessed 2016 Oct 6]. Available from: archive.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/mortality/Hughes3.html.

17. National Cancer Institute. [Internet] Joinpoint regression program,version 4.2.0.2. Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch and Data Modeling Branch, Surveillance Research Program 2015.[accessed 2015 Jan 4]. Available from: surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/.

18. Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000;9(3):335—51.

19. Houchens RL, Elixhauser A. [Internet] Using the HCUP nationwide inpatient sample to estimate trends (updated for 1988—2004).HCUP methods series report # 2006-05 online; 2006. [accessed 2016 Oct 6]. Available from: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/2006_05_NISTrendsReport_1988-2004.pdf.

20. Morden NE, Chang CH, Jacobson JO, Berke EM, Bynum JP,Murray KM, et al. End-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer is highly intensive overall and varies widely. Health Aff(Millwood) 2012;31(4):786—96.

21. Ramondetta LM, Tortolero-Luna G, Bodurka DC, Sills D, Basen-Engquist K, Gano J, et al. Approaches for end-of-life care in the fi eld of gynecologic oncology: an exploratory study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2004;14(4):580—8.

22. Hogan C, Lunney J, Gabel J, Lynn J. Medicare beneficiaries’ costs of care in the last year of life. Health Aff (Millwood)2001;20(4):188—95.

23. Clark D. From margins to centre: a review of the history of palliative care in cancer. Lancet Oncol 2007;8(5):430—8.

24. Eichler AF, Lamont EB. Utility of administrative claims data for the study of brain metastases: a validation study. J Neurooncol 2009;95(3):427—31.

25. Whyte JL, Engel-Nitz NM, Teitelbaum A, Rey GG, Kallich JD.An evaluation of algorithms for identifying metastatic breast,lung, or colorectal cancer in administrssative claims data. Med Care 2015;53(7):e49—57.

26. Hua M, Li G, Clancy C, Morrison RS, Wunsch H. Validation of the V66.7 code for palliative care consultation in a single academic medical center. J Palliat Med 2016.

27. Qureshi AI, Adil MM, Suri MF. Rate of utilization and determinants of withdrawal of care in acute ischemic stroke treated with thrombolytics in USA. Med Care 2013;51(12):1094—100.

28. Mulvey CL, Smith TJ, Gourin CG. Use ofinpatient palliative care services in patients with metastatic incurable head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2016;38(3):355—63.

29. Okafor PN, Stobaugh DJ, Nnadi AK, Talwalkar JA. Determinants of palliative care utilization among patients hospitalized with metastatic gastrointestinal malignancies. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2017;34(3):269-274.

1. Department of Family and Community Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston,TX, USA

Jason L. Salemi, PhD, MPH

Department of Family and Community Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, 3701 Kirby Drive,Suite 600, Houston, TX 77098,USA

Tel.: +1-713-7984698

E-mail: jason.salemi@bcm.edu

10 January 2017;Accepted 14 March 2017

杂志排行

Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Temporal trends in colorectal cancer inci dence among Asian American populations in the United States, 1994–2013

- Primary and secondary prevention of colorectal cancer: An evidencebased review

- Modifi ed Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics course: Feasibility,trainee satisfaction, and sustainability potential

- Ten year risk assessment ofischemic cardiovascular disease and intervention analysis among middle-aged residents with moderate risk and above in a Shanghai-based community

- Characteristics of patients with erectile dysfunction in a family physician-led erectile dysfunction clinic: Retrospective case series

- Student self-assessment versus preceptor assessment at the midpoint of a family medicine clerkshipa