聚丙烯酸功能化高效发光的La1−xEuxF3纳米晶合成及细胞成像

2017-11-01王中跃张艳艳余柯涵翁丽星

陈 凡 王中跃,* 张艳艳 余柯涵 翁丽星 韦 玮,*

(1南京邮电大学光电工程学院,南京 210023;2南京邮电大学信息材料与纳米研究院,南京 210023)

聚丙烯酸功能化高效发光的La1−xEuxF3纳米晶合成及细胞成像

陈 凡1王中跃1,*张艳艳1余柯涵1翁丽星2韦 玮1,*

(1南京邮电大学光电工程学院,南京 210023;2南京邮电大学信息材料与纳米研究院,南京 210023)

采用水热合成一锅法制备了聚丙烯酸功能化单分散的La1−xEuxF3纳米颗粒(La1−xEuxF3@PAA NPs)。利用透射电子显微镜(TEM)、X射线衍射(XRD)、傅里叶变换红外光谱(FTIR)和光致发光光谱(PL)对样品的形貌、结构、组成和荧光性能进行表征。该纳米颗粒平均粒径为(7 ± 3) nm,具有较好的分散性、稳定性与生物相容性。将纳米颗粒与HeLa癌细胞共同孵育,体外成像结果表明材料对HeLa癌细胞显示出低细胞毒性。用水热法制备的La1−xEuxF3@PAA纳米颗粒可以作为光学荧光探针用于细胞成像,在生物医学领域表现出巨大的潜力。

稀土纳米颗粒;水热法;水分散液;高效发光;生物成像

1 Introduction

With the tremendous developments of fluorophores in the past decades, fluorescent bioimaging has been emerging as an important technique in diagnosis and treatment of a variety of diseases1−4. Organic dyes and quantum dots (QDs) are most intensively investigated optical probes in clinical diagnostic applications due to their bright fluorescence while both of them have certain limitations5−7. For example, organic dyes are easilysubject to photo-bleaching and luminescence blinking in view of the mutability of conjugating π-electrons8,9. The heavy mental ions in QDs (e.g., Cd3As2, PbSe and so on) possess serious toxicity though they show superior photostability and high resistance to photobleaching10,11. Hence, finding an appropriate substitute for the existing biological probes is still under active exploration.

Recently, lanthanide nanoparticles (Ln NPs) have stood out from the competition in the field of fluorescent bioimaging owing to their remarkable features: (1) high photochemical stability and high PL quantum yield (QY); (2) long luminescence lifetimes (microsecond to millisecond); and (3)low toxicity12−15.

Aqueous dispersity of nanomaterials is a prerequisite for biomedical applications, so are the lanthanide luminescent bioprobes3,16,17. Nonetheless, most as-prepared nanoparticles cannot suspend in water steadily10. Recently, Mimun et al.18studied the stability of GdF3:Nd3+nanophosphor suspension in the deionized (DI) water, but aggregation appeared in two days. Inorganic or organic surface modification can be applied to transform the hydrophobic of Ln NPs to the hydrophilic and stabilize the dispersion19. For example, a SiO2layer was coated on NdF3NPs to obtain biocompatible and highly-efficient fluorescent core-shell NdF3/SiO2NPs20. Chitosan/LaF3:Eu3+nanoparticles (NPs) with excellent dispersity in aqueous solution were prepared using a one-pot method21. Nevertheless, these surface modifying methods either need complex procedure22, or lead to low QY that impacts greatly on high-contrast between bioimaging and fluorescence background12,13, or have limited stability18. A facile synthetic procedure to obtain stable and highly luminescent Ln NP aqueous dispersion is needed urgently.

Herein, we report on a simple preparation of stable La1−xEuxF3NP aqueous dispersion with polyacrylic acid (PAA)as a surface modifying agent with a one-pot hydrothermal synthesis. The optimum PAA-functionalized La1−xEuxF3nanospheres present a high stability not only in DI water, but also in phosphate buffer solution (PBS), which is one of the most frequently used biological buffers. In addition, we incubate La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs with HeLa cancer cells at different concentrations and hours to study the cellular toxicity and cell uptake of La1−xEuxF3@PAA NPs.

2 Experimental and computational section

2.1 Materials

All starting materials were obtained from commercial supplies and used as received. La(NO3)3·6H2O (99.9%),Eu(NO3)3·6H2O (99.9%), and NH4F(96%) were purchased from Alfa Aesar. Polyacrylic acid (PAA, MW= 3000) was obtained from Aladdin Chemistry Co., Ltd. Ethyl alcohol was supplied from Yasheng Chemical Co., Ltd. DI water was throughout.

2.2 Characterization

The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) rings were carried out on a JEM-2100F emission transmission electron microscope. The X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) patterns were measured on a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray powder diffractometer. The emission spectra were measured by full-featured steady state/transient fluorescence spectrometer FLS920 from Edinburgh Instruments. Digital photographs of the NP dispersion were taken by a digital camera (Sony T7)without image processing. The fluorescence micrographs were observed under a con-focal laser scanning microscope(Olympus FluoView™ FV1000) made in Japan. All the photoluminescence studies were carried out at room temperature.

2.3 Synthesis of La1−xEuxF3@PAA

The La1−xEuxF3@PAA NPs were synthesized using a hydrothermal method. In a typical procedure23,24, weighted amount of La(NO3)3and Eu(NO3)3were dissolved in deionized water (19 mL) and ethyl alcohol (45 mL) under magnetic stirring, and the total rare earth ion molar concentration was 0.5 mmol. Then 125 mg PAA was added to the Ln-containing solution under magnetic stirring at 80 °C to form a clear solution. After that, 2 mmol NH4F was added and stirred for 10 min. The mixture was transferred into a 100 mL Teflon-lined autoclave, and elevated up to 160 °C for 12 h. The as-prepared NPs were separated by centrifugation for 15 min at 1.05 × 104r·min−1and re-dispersed in water for several times, and then were finally dispersed in DI water.

2.4 Photoluminescence bioimaging in vitro

To evaluate the capability of in-vitro PL optical bioimaging of La1−xEuxF3@PAA NPs, HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco′s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10%fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin and streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The biological imaging was evaluated by utilizing the confocal laser scanning microscope. All La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NP aqueous solutions to the cells experiment were dispersed in PBS.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Synthesis and characterization of La1−xEuxF3@PAA

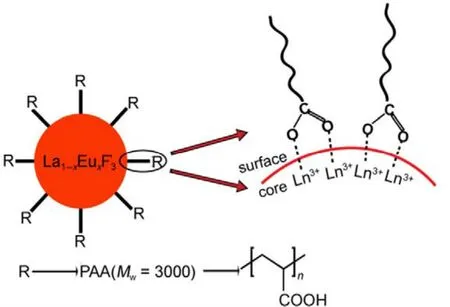

In the one-pot green hydrothermal process (Fig.1), a coordinative polymer (PAA) was introduced to mediate the precipitation and the crystallization process of the La1−xEuxF3NPs to prevent the rapid precipitation of Ln fluorides in water25.

During the process of the growth of La1−xEuxF3@PAA NPs,an almost constant cation concentration was maintained by the equilibrium between coordination and precipitation. In addition,PAA also encapsulated the NPs without further aggregation20.Finally, the crude NPs underwent recrystallization into nanosized single-crystal in hydrothermal treatment, as verified by high resolution TEM (Fig.2C).

Fig.1 Schematic illustration of La1−xEuxF3 NPs surface with PAA coating.

Fig.2A and C show the TEM images of the as-prepared NPs,the monodispersed La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs are irregular plate-like in shape, with an average diameter of (7 ± 3) nm(Fig.2B). Notably, NPs smaller than 10 nm could be excreted more efficient in human body, and allow the use of higher dose of imaging agents26,27. The SAED rings in Fig.2D reflect the random orientation of nano-crystalline particles, and the SAED patterns agree well with the diffractions from the (111), (112),and (113) planes of the hexagonal LaF3.

The XRD patterns of La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs and the standard diffraction lines of the hexagonal LaF3crystal (JCPDS No. 32-0483) are shown in Fig.3A. The diffraction peaks of the La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs (the curve) match the pure hexagonal LaF3phase (the vertical lines) very well, which is in accordance with the SAED analysis. Additionally, no trace of characteristic peak for impurity phase was observed, indicating a pure phase of LaF3NPs prepared with the feasible one-step synthesis route. The compositional distribution of the La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA nanocrystals was obtained by energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) analysis (Fig.3B). From the EDS pattern, the EDS signals of La, F, C, O, and Eu can be clearly observed across the region of the nanocrystals.

Fig.2 TEM particle size distribution and SAED patterns of La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs.

Fig.3 XRD and EDS patterns of La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA nanoparticles.(A) XRD patterns; (B) EDS patterns

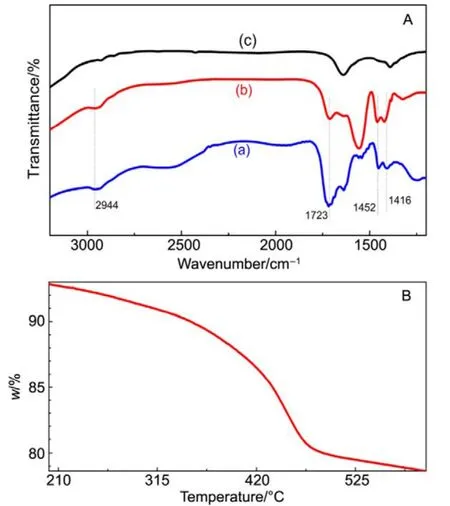

Fig.4 FT-IR spectra and thermogravimetric curve of La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs.

By attaching onto the surface of the nanoparticles,hydrophilic polymer, PAA, endows the La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA nanocrystals with excellent dispersibility in aqueous solution,as required in biomedical imaging and cancer therapy. In order to confirm that the surface of nanoparticles was modified by PAA, the FT-IR spectra of La0.5Eu0.5F3nanoparticles,La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA nanoparticles, and pure PAA were measured. As shown in Fig.4A(a) and (b), two characteristic bands resulting from the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the C―O in COOH group can be observed at 1452 and 1416 cm−1respectively. The band at 2944 cm−1was assigned to the stretching vibration of the methylene(CH2) in the long alkyl chain of PAA, and another peak corresponding to the stretching modes of C=O in COOH group was also observed at 1723 cm−1. However, these four characteristic absorption peaks of PAA could not be observed in Fig.4A(c),except the distinguishable band at 1642 cm−1resulting from the La-O vibration in impurities caused by the presence of H2O during the reaction28. The result clearly indicated that a large amount of PAA capped on the surface of La0.5Eu0.5F3nanoparticles. For investigating the content of PAA, the thermogravimetric analysis was done. As shown in Fig.4B, the weight loss induced by the decomposition of PAA reached~14% (w) from 200 to 600 °C, consistent with previous reports29. At the same time, the mass losses further confirm the surface functionalization of PAA on La0.5Eu0.5F3nanoparticles.

3.2 Photoluminescence properties

Fig.5 Emission spectra and the decay curve of the La1−xEuxF3@PAA NPs.

In order to study the effect of Eu3+concentration on the photoluminescence properties of La1−xEuxF3@PAA nanocrystals aqueous dispersion, the emission spectra and the luminescent decay curves of La1−xEuxF3@PAA nanocrystals aqueous dispersion with different Eu3+ions concentration were recorded at room temperature (Fig.5).Fig.5A exhibits the emission spectra of La1−xEuxF3NPs aqueous dispersions under 393 nm excitation with x values of 0.01, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0 respectively. Four fluorescence peaks corresponding to the transitions from5D0to7FJ(J = 0,1, 2, 4) of Eu3+ions were clearly observed. Increasing Eu3+concentration, the fluorescent intensity increased for low concentration and then decreased when x value is greater than 0.5. The cross-relaxation dominated the electron transition and thus decreased the luminescent intensity at high Eu3+concentration (x > 0.5). Fig.5B illustrates the fluorescence decay curves of La1-xEuxF3@PAA NP aqueous dispersion by monitoring the5D0→7F2at 613 nm under 393nm excitation. The lifetimes of La1−xEuxF3@PAA NPs in aqueous solution were calculated by fitting the decay curves with a single exponential decay. The lifetimes were about 4.57, 2.58, 1.93, 1.17, and 0.60 ms for x value of 0.01, 0.25,0.5, 0.75, 1.0, respectively. The increasing Eu3+concentration shortened the NPsʹ lifetime, which was caused by “concentration quenching effect”, in good agreement with the change of fluorescence intensity.

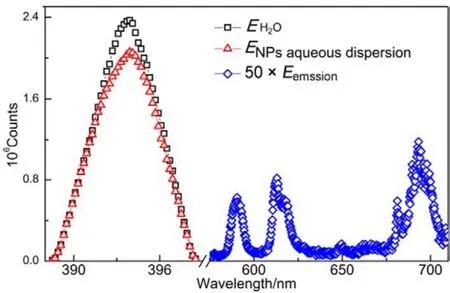

Fig.6 QY spectra of La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NP aqueous dispersion.

Fig.7 PL intensity of La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs dispersed in DI water at different time.

The absolute QY for La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NP aqueous dispersion was estimated to be as high as 66%, which meets the requirements of ideal photoluminescent probes for in vitro and in vivo imaging. The QY can be represented simply in the following formula:

QY = ∫Eemssion/(∫Esolvent− ∫Esample)

where ∫Eemssionis the integration of the luminescence emission spectrum of the sample; ∫Esampleis the integration of the spectrum of the light used to excite the sample (ENPaqueousdispersionin our case); ∫Esolventis the integration of the spectrum of the light used for excitation with the solvent only (EH2Oin our case). The QY spectra of La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NP aqueous dispersion are shown in Fig.6.

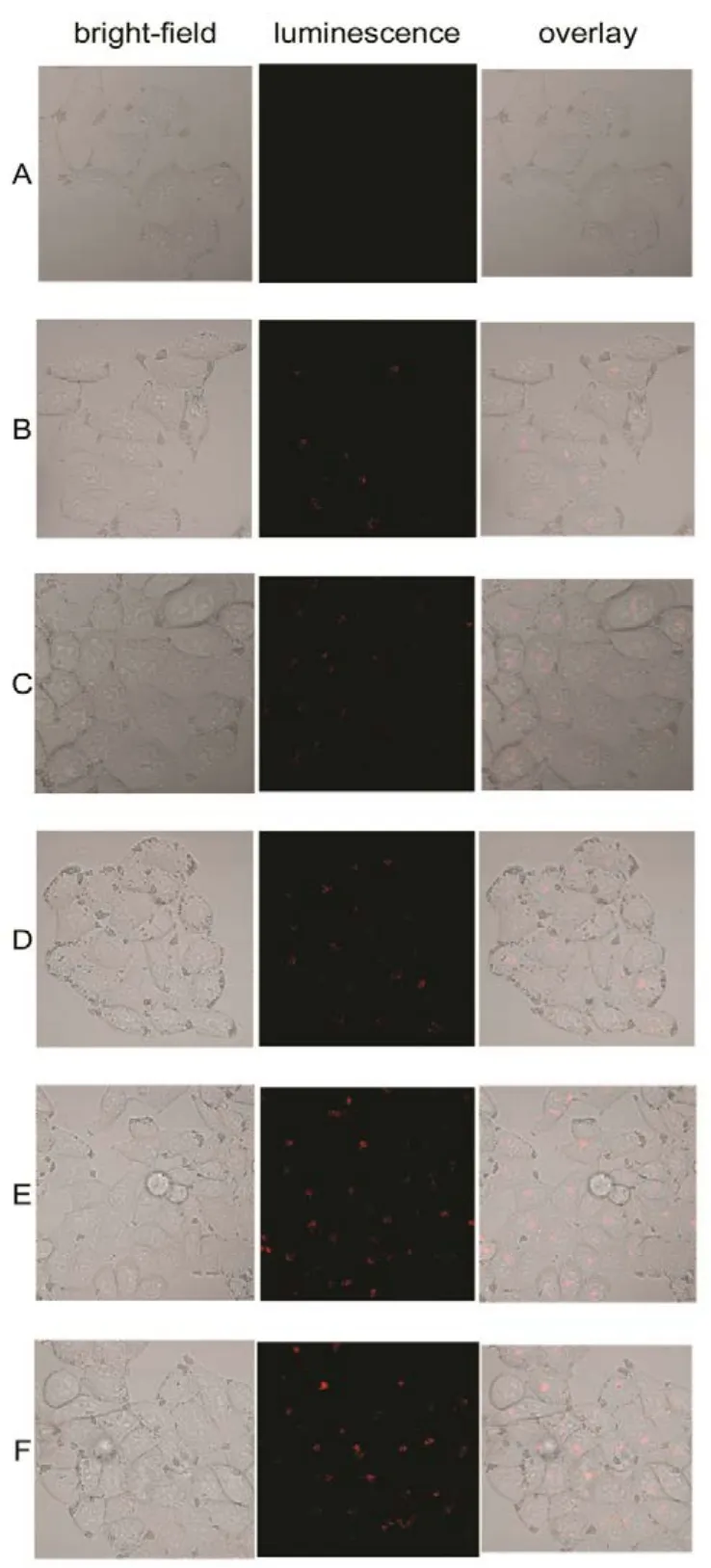

Fig.8 Confocal fluorescent microscopy images of HeLa cancer cells incubated with La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs at a concentrations of 500 μg·mL−1 for different time. Each series shows a bright-field image, luminescent image, and the overlay.

To confirm the photostability of La1−xEuxF3@PAA NPs aqueous dispersion, we acquired the fluorescence spectra of La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA nanocrystals dispersed in DI water for extended periods of time (Fig.7). Even after two mouths, the fluorescence intensity almost remained unchanged. As shown in below inset (left) of Fig.7, bright red luminescence under irradiation of a 4 W hand-held UV lamp (365 nm) was observed. High photostablity and efficient red-light emission suggested that La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA nanocrystals were a type of attractive luminescent probes because these nanocrystals emitting in the red and near-infrared regions are preferred for in vivo biological imaging.

3.3 In vitro photoluminescence imaging of HeLa cancer cells

Fig.9 Confocal fluorescent microscopy images of washed HeLa cancer cells incubated with La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs at a concentrations of 500 μg·mL−1 for different time.

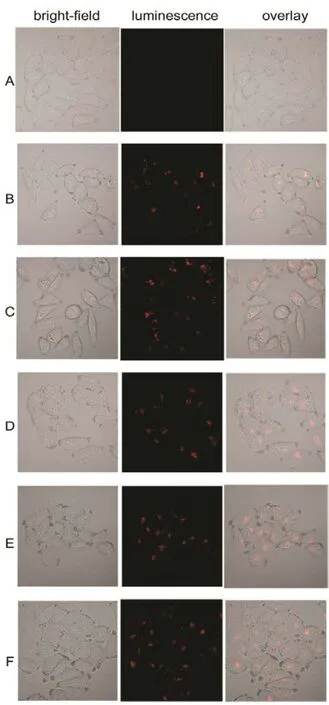

Fig.10 Confocal fluorescent microscopy images of HeLa cancer cells incubated with La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs for 4 hours at different concentrations from 500 to 3000 μg·mL−1.

To evaluate the capability of La1−xEuxF3@PAA as a nanoprobe for optical bioimaging, PL imaging in vitro of HeLa cancer cells incubation with La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA was investigated by utilizing a con-focal laser scanning microscope equipped with excitation at 515 nm, PL signals were collected at 600−650 nm. Besides, a cell control was also investigated. With the prolonging of incubation time, as shown in Fig.8, the luminescence intensity in HeLa cells enhanced obviously, suggesting that an increasing number of NPs were taken up by the HeLa cells. Moreover, the bright field images of the cells were also observed for comparison to the confocal fluorescent microscopy images, which indicates that the bright-field images of the cells significantly overlapped with the confocal images. In addition, the HeLa cells still maintain good morphology after 6 hoursʹ incubation except few dead cells, which means that the best incubation time of HeLa cells with La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs at a concentrations of 500 µg·mL−1to keep good morphology is about 4 hours.

After each incubation time, the HeLa cells were washed twice by PBS to remove the NPs which were on the surfaces of the cells, so as to confirm that the red luminescence came from the interior of the cells. Fig.9 shows the confocal fluorescent microscopy images of the washed HeLa cells. An obviously increasing visible luminescence signal can be detected over the course of time, implying that La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs indeed gone inside the cells rather than adhered to the cell surface.

In order to determine the impact of NPs concentration on HeLa cells morphology, the florescence microscopy images of HeLa cancer cells incubated with La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs for 4 h at 37 °C for different concentrations from 500 to 3000 μg·mL−1were taken, as shown in Fig.10. With the incubation concentration increasing, the luminescence intensity strengthened clearly except minor difference for higher concentration above 1000 μg·mL−1. Besides, the morphology became coarser when the concentration reached 1500 μg·mL−1. Therefore, the ideal incubation concentration is 1000 μg·mL−1.

4 Conclusions

In conclusion, monodisperse La1−xEuxF3NPs functionalized by PAA have been prepared through one-step facile hydrothermal approach. It is found that these NPs were fluorescent and had an average size of (7 ± 3) nm. PAA was applied to cap the nanoparticles during the synthesis process,which rendered them water soluble and provided functional chemical groups, such as amino groups on the nanoparticles.These nanoparticles exhibited absolute QY of 66% with x value of 0.5, and showed great dispersion stability and photoluminescence stability within a time period of at least two months. Meanwhile, no measurable cytotoxicity was observed in HeLa cells for the La0.5Eu0.5F3@PAA NPs concentration up to 3000 μg·mL−1. Therefore, the generality of one-pot method can be extended to synthesize of La1−xEuxF3NPs with FA and other functional ligands with a carboxyl group, which opens up a new perspective for preparing surface-functionalized ligands for biolabelling and targeted imaging.

(1) Fu, X. Y.; Shao, G. S.; Han, R. C.; Ma, Y.; Xue, F. M.; Yang, F.; Fu,L. M.; Zhang, J. P.; Wang, Y. Acta Phys. -Chim. Sin. 2012, 28, 2480.[符小艺, 邵光胜, 韩荣成, 马 严, 薛富民, 杨 帆, 付立民, 张建平, 王 远. 物理化学学报, 2012, 28, 2480.]doi: 10.3866/PKU.WHXB201208161

(2) Ferrari, M. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 161. doi: 10.1038/nrc1566

(3) Lv, R.; Yang, G.; He, F.; Dai, Y.; Gai, S.; Yang, P. Nanoscale 2014,6, 14799. doi: 10.1039/c4nr04336g

(4) Riehemann, K.; Schneider, S. W.; Luger, T. A.; Godin, B.; Ferrari,M.; Fuchs, H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 872.doi: 10.1002/anie.200802585

(5) Michalet, X.; Pinaud, F. F.; Bentolila, L. A.; Tsay, J. M.; Doose, S.;Li, J. J.; Sundaresan, G.; Wu, A. M.; Gambhir, S. S.; Weiss, S.Science 2005, 307, 538. doi: 10.1126/science.1104274

(6) Dubertret, B.; Skourides, P.; Norris, D. J.; Noireaux, V.; Brivanlou,A. H.; Libchaber, A. Science 2002, 298, 1759.doi: 10.1126/science.1077194

(7) Yuwen, L. H.; Xue, B.; Wang, L. H. Acta Phys. -Chim. Sin. 2014, 30,994. [宇文力辉, 薛 冰, 汪联辉. 物理化学学报, 2014, 30, 994.]doi: 10.3866/PKU.WHXB201403131

(8) Widengren, J.; Chmyrov, A.; Eggeling, C.; Löfdahl, P. A.; Seidel, C.A. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 429. doi: 10.1021/jp0646325

(9) Eggeling, C.; Widengren, J.; Brand, L.; Schaffer, J.; Felekyan, S. A.;Seidel, C. A. M. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 2979.doi: 10.1021/jp054581w

(10) Barreto, J. A.; O'Malley, W.; Kubeil, M.; Graham, B.; Stephan, H.;Spiccia, L. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 18. doi: 10.1002/adma.201100140

(11) Sutherland, A. J. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2002, 6, 365.doi: 10.1016/S1359-0286(02)00081-5

(12) Chen, G.; Ohulchanskyy, T. Y.; Liu, S.; Law, W. C.; Wu, F.; Swihart,M. T.; Ågren, H.; Prasad, P. N. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 2969.doi: 10.1021/nn2042362

(13) Bouzigues, C.; Gacoin, T.; Alexandrou, A. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 8488.doi: 10.1021/nn202378b

(14) Vetrone, F.; Capobianco, J. A. Int. J. Nanotechnol. 2008, 5, 1306.doi: 10.1504/IJNT.2008.019840

(15) Shen, J.; Sun, L. D.; Yan, C. H. Dalton Trans. 2008, 42, 5687.doi: 10.1039/b805306e

(16) Bünzli, J. C. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2729. doi: 10.1021/cr900362e

(17) Li, F.; Li, C.; Liu, X.; Bai, T.; Dong, W.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Z.; Feng, S.Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 2015. doi: 10.1039/c2dt32295a

(18) Mimun, L. C.; Ajithkumar, G.; Pokhrel, M.; Yust, B. G.; Elliott, Z. G.;Pedraza, F.; Dhanale, A.; Tang, L.; Lin, A. L.; Dravid, V. P. J. Mater.Chem. 2013, 1, 5702. doi: 10.1039/C3TB20905A

(19) Ghosh, C. R.; Paria, S. Chem. Rev. 2011, 112, 2373.doi: 10.1021/cr100449n

(20) Yu, X. F.; Chen, L. D.; Li, M.; Xie, M. Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.Q. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 4118. doi: 10.1002/adma.200801224

(21) Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, X.; Wang, M. Nanotechnology 2006, 17,1527. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/17/5/060

(22) Ma, Z. Y.; Dosev, D.; Nichkova, M.; Gee, S. J.; Hammock, B. D.;Kennedy, I. M. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 4695.doi: 10.1039/b901427f

(23) Zhang, W.; Hua, R.; Shao, W.; Zhao, J.; Na, L. J. Nanosci.Nanotechnol. 2014, 14, 3690. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2014.7971

(24) Wu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Zhu, Y. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem.2011, 2011, 2158. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201001149

(25) Tian, Y.; Tian, J.; Li, X.; Yu, B.;Shi, T. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47,2847. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04952b

(26) Gupta, B. K.; Narayanan, T. N.; Vithayathil, S. A.; Lee, Y.; Koshy, S.;Reddy, A. L. M.; Saha, A.; Shanker, V.; Singh, V. N.; Kaipparettu, B.A. Small 2012, 8, 3028. doi: 10.1002/smll.201200909

(27) Chen, G.; Ohulchanskyy, T. Y.; Kumar, R.; Agren, H.; Prasad, P. N.ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3163. doi: 10.1021/nn100457j

(28) Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y. Nano Res. 2010, 3, 317.doi: 10.1007/s12274-010-1035-z

(29) Ju, Q.; Luo, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Li, R.; Chen, X. Nanoscale 2010, 2,1208. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00116c

Synthesis of Poly(acrylic acid)-Functionalized La1−xEuxF3Nanocrystals with High Photoluminescence for Cellular Imaging

CHEN Fan1WANG Zhong-Yue1,*ZHANG Yan-Yan1YU Ke-Han1WENG Li-Xing2WEI Wei1,*

(1School of Optoelectronic Engineering, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Nanjing 210023, P. R. China;2Institute of Advanced Materials, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Nanjing 210023, P. R. China)

Monodisperse La1−xEuxF3nanoparticles (NPs) were functionalized by poly(acrylic acid) (PAA)via a one-pot modified hydrothermal method. The morphology, crystal structure, surface groups, and luminescence properties of the as-produced La1−xEuxF3@PAA NPs were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy. The produced nanoparticles were (7 ± 3) nm in size, water soluble,and buffer stable, with good photostability and biocompatibility. In vitro imaging revealed the low cytotoxicity of the as-synthesized NPs incubated with HeLa cancer cells. Thus, the colloidal La1−xEuxF3@PAA NPs exhibit great potential for use as optical imaging probes in biological applications.

Lanthanide nanoparticle; Hydrothermal; Aqueous dispersion; Efficient luminescence;Bioimaging

January 3, 2017; Revised: March 3, 2017; Published online: April 10, 2017.

O648

10.3866/PKU.WHXB201704102 www.whxb.pku.edu.cn

*Corresponding authors. WEI Wei, Email: weiwei@njupt.edu.cn. WANG Zhong-Yue, Email: zywang@njupt.edu.cn; Tel: +86-25-85866400.

The project was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB933301) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (51502144).国家重点基础研究发展计划项目(2012CB933301)和国家自然科学基金项目(51502144)资助

© Editorial office of Acta Physico-Chimica Sinica