An Orchid in a Traditional Garden

2017-08-03ByPanXiaoqiao

By+Pan+Xiaoqiao

Imagin a star performer at the age of 60 still retaining the charisma of their heyday and keeping the audience enthralled during a three-hour performance, and you have the profi le of the Beijing-based Northern Kunqu Opera Theater (Beikun), which has had the honor of performing in the 2012 London Olympics and re-popularizing an art form that is 600 years old.

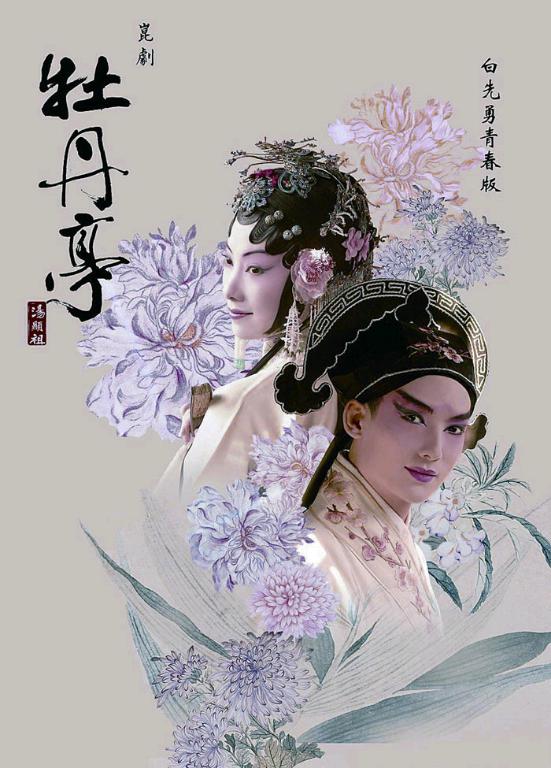

To celebrate its 60th birth anniversary, Beikun served a cultural feast at the Tianqiao Performing Arts Center in Beijing in June, performing Peony Pavilion, a Kunqu Opera masterpiece based on the eponymous romance by Tang Xianzu, a dramatist and writer in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) who was William Shakespeares contemporary, and other masterpieces, marking a Kunqu renaissance.

Peony Pavilion was staged with seven actresses playing the role of Du Liniang, the heroine, while six actors were cast as Liu Mengmei, the hero. By having several performers play the same role, Beikun offered its young cast an opportunity to go on stage while the audience could see different performing styles.

New life for an ancient art

“During the anniversary week performances, more people got to know about Kunqu and Beikun,” Yang Fengyi, Director of Beikun, said.“Our performers also harvested a lot of benefi ts. Particularly, their confidence in Kunqu Opera and in themselves was renewed. The audiences passion and support will encourage us to perform more and let more people know about Kunqu.”

Beikun, established in 1957, is the only professional Kunqu opera troupe north of the Yangtze River. Apart from regular performances and tours, the recent years have seen it becoming increasingly active in propagating the opera among young students in universities. In April, Beikun sent a team to Wuhan, central Chinas Hubei Province, to stage Peony Pavilion in fi ve universities, and also to deliver an art appreciation lecture on Kunqu Opera.

Shao Tianshuai, a rising star in Beikun, participated in the evening gala of the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing on May 14.

“I was very excited to know that I had been selected,” Shao said. “I was happy not only for myself but also for Kunqu. The chance was a milestone in the history of the opera. There was no Kunqu Opera performance in last years G20 Summit in Hangzhou. So it was very encouraging to be selected. We were proud and pleased to see Kunqu so well received by leaders from around the world.”

According to Yang, in the past, when Beikun planned performance tours abroad, it was not easy to get a foreign government department or organization willing to host them. But in the past years, they have been frequently invited to perform around the world.

Last year, a Beikun delegation visited Hungary and the Chinese and Hungarian cultural authorities decided that the story of Princess Sissi, Austrias longest-serving empress Elisabeth who was married to Emperor Franz Joseph I, would be enacted as a Kunqu Opera performance.

Beikun toured Austria with two operas, Snow in Summer, a masterpiece by playwright Guan Hanqing (1241-1320) chronicling the suffering of a filial daughter in law, and Peony Pavilion.

“There were no English subtitles or microphones and yet the nearly 1,000-strong audience watched in rapt silence,” Yang said.“Snow in Summer is very diffi cult to understand, even for a Chinese audience, but everyone there was listening intently and quietly. Later, a lot of people came to tell us that they like the costumes, headdresses, music and almost everything we showed them.”

The tour, Yang added, convinced her that traditional Chinese performing arts have a potential huge audience base in the world.

Mother of all operas

With a history of more than 600 years, Kunqu is believed to be the mother of all traditional operas in China, showcasing the very essence of ancient Chinese music and performing art.

China is home to more than 300 genres of traditional opera, which can be divided into roughly two categories: the Peking Opera type and operas which follow the qupai or fixedmelody style. Of all traditional operas that use qupai, Kunqu follows the strictest rules. Performers sing to the accompaniment of traditional Chinese musical instruments like the fl ute, pipa or lute, the zither-like guzheng, and percussions.

Kunqu Opera boasts of excellent drama scripts, which are literary masterpieces in themselves like Peony Pavilion, The Palace of Eternal Youth, a 17th-century classic about an emperors obsessed love for a lady in the court which leads to a coup and tragedy, and The Peach Blossom Fan, a play that chronicles the fall of the Ming Dynasty and reportedly took playwright Kong Shangren (1648-1718) more than a decade to write. The monologues by the leading characters are poetic, written in beautiful and romantic language.

Love is a permanent theme of Kunqu Opera. “The beauty of Kunqu is refl ected in the way it understands, depicts and expresses sentiments, [especially] love,” said Zhang Jingxian, a Kunqu artist acclaimed as a national intangible cultural heritage bearer. “Take Peony Pavilion for example. Du Liniang is conf ined to her residence but still pursues love with valor.She is even willing to die for true love, hoping she will be resurrected. This was not a common notion in the feudal society 600 years ago and is an important reason why Peony Pavilion is still so popular in todays modern society,” said Zhang.

Given the sophisticated script, strict singing and performance criteria, and most importantly, the complicated sentiments to be conveyed, the bar for Kunqu performers is set very high. In the Kunqu Opera circle, there is a common saying that one minute on stage needs 10 years of practice.

According to Shao, they have to read the script diligently, using ancient Chinese dictionaries to comprehend the meaning of each character. Then they have experienced teachers critiquing performances to push the performers closer to perfection.

Wang Pushi is studying Kunqu in Beijing Traditional Chinese Arts School. The 17-yearold was allowed to make his stage debut only after three and a half years of studying the opera. “I have to work very hard. Im afraid I might damage its beautiful image if I treat it casually,”the teenager said.

Ups and downs

Kunqu Opera began to take shape in the Ming Dynasty and reached its zenith in the late 16th century. According to historical records, during the reign of Emperor Wanli (1573-1620), in Suzhou of east Chinas Jiangsu Province alone, regarded as the birthplace of Kunqu, there were several thousands of professional performers, much more than the total number today.

The genre once outshone almost all other traditional operas and kept prospering for more than two centuries. However, by the middle of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), it gradually lost its vitality, the decline largely attributed to the lack of new dramas after master playwrights like Tang passed away. Another reason was it being out of reach of ordinary people. Without a certain level of cultural or literary knowledge, it is impossible to understand Kunqu, let alone appreciate it.

Ke Jun, head of Jiangsu Provincial Kunqu Opera Theater, gave a bleak picture of the situation in rural Suzhou in the 1990s in a past interview: “That day, there were 20 performers on stage but only three people in the audience, of whom, one was sleeping, one was walking around and the third was cracking and eating melon seeds.”

In 2000, Suzhou hosted the first China Kunqu Opera Festival. Held every three years, the successive editions have been presenting newly adapted classic dramas, bringing a lot of excellent plays and performers in the limelight. In 2001, Kunqu Opera joined UNESCOs Intangible Cultural Heritage List and since then, the opera began to regain its rightful place in modern times.

Kunqu is an art form that is handed down to students by teachers orally and through demonstrations. Chinas Ministry of Culture has been offering a bonus of 20,000 yuan ($3,000) to teachers who teach one classic Kunqu drama to a student to encourage the propagation of more classics.

The opera now faces a critical question: How to balance inheritance with innovation?“No one knows what Kunqu Opera was like 600 years ago as it kept changing to meet audiences changing aesthetic tastes. You have to keep moving forward. But you should never abandon the roots or it would no longer be Kunqu Opera,” Yang said.

A successful example is Beikuns new adaptation, A Dream of Red Mansions, based on the eponymous semi-autobiographical 18thcentury novel, where violin has been added to the original band. “This change was widely accepted by the audience, who felt the violin made the music sweeter, without changing the essence or style of Kunqu music,” Yang said. As she sees it, innovation comes from the natural development of the art, rather than from changes made solely for the sake of innovation.

Catching young peoples fancy

Yu Hao, who was avidly watching Beikuns anniversary performance, said she saw her first Kunqu Opera seven years ago. “I was captivated by Cui Yingying, the pretty heroine of The Romance of the West Chamber, and since then have been irreversibly in love with Kunqu Opera,” she said.

Though traditional operas in China are generally favored by the elderly, in recent years, Kunqu is becoming a fad among young people. This is largely attributed to the youth-oriented version of Peony Pavilion adapted by Pai Hsienyung, a contemporary writer in Taiwan, in 2004. While some critics panned it for the “excessively modern” stage-setting, it has been well received by the audience, who otherwise may never have been attracted to the theater and Kunqu Opera.

Pais version was performed for three nights in central Chinas Wuhan University in April 2008, with all the 6,000 tickets sold out. Students chose to stand in the aisles to watch, instead of going away.

When asked the reason for young peoples rising interest in Kunqu Opera, Yang said she had asked the young fans the same question.“They all tell me its because Kunqu Opera is so beautiful. The language is poetic, the music silky and the actors motions graceful, making the opera attractive to the young, who hope to improve their cultural quality through watching or even learning to play the Kunqu Opera.”

Yang also felt that young peoples exposure to foreign cultures had grown more than ever before. Consequently, some of them are beginning to look for the very essence of Chinese culture. Besides, young people also have the cultural knowledge required to understand and appreciate Kunqu Opera.

Liu Xuan, a classmate of Wang in Beijing Traditional Chinese Arts School, has chosen to study Kunqu Opera because she thinks though it is hard to master, the opera improves her cultural aura and overall quality. “It is really beautiful and elegant and worth hard work,” she said. Lius aim is to work hard and get admitted to the Central Academy of Drama and then become a Beikun troupe member.

In two years time, Beikun will see a new office building coming up, designed to be a modern, comprehensive and international art center. It will comprise three theaters, rehearsal studios and also a Kunqu Opera museum, giving Kunqu lovers, especially young people, easier access to the ancient art.