An Early Start

2017-07-21ByHouWeili

By+Hou+Weili

Liu Ying can hardly remember the last time she had a free weekend. As the person in charge of business development at MAMALOOK, a Beijing-based company providing English language training to kids, the 29-year-old saw her workload increase drastically over the past few months together with the rapid expansion of her business.

“My schedule is so tight. Our English training solution is in high demand and investors are beating down my door to become franchisees,” Liu said. Since its first language training outlet opened in May 2014, MAMALOOK, which serves children aged two to 12, has expanded its franchise network to 51 locations across China, with another 20 under negotiation.

This mirrors the Chinese private sectors growing interest in education services over the past few years. As the middle class expands and parents, especially those born in the 1980s, attach more and more importance to their kids preschool education, the demand for early education services is growing and becoming more diversified. As a result, private investment started flowing into the early education sector.

The market value of early education businesses for kids aged zero to six, for example, is expected to reach 300 billion yuan ($43.5 billion) in 2020, according to a report by Forward Business Information Co. Ltd., an investment consultancy firm based in Shenzhen in south Chinas Guangdong Province.

Driven by demand

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, a total of 17.86 million infants were born in China in 2016. The annual fi gure stood at around 16 million from 2010-13 and slightly increased in 2014 and 2015 with the further relaxation of Chinas family planning policy. The countrys population of children aged zero to six was estimated to have exceeded 100 million in 2016.

“It is such a large population, and this is what makes investors bullish on business prospects for preschool education,” Liu said, noting that the bulk of this lucrative market will be tapped in the next fi ve to 10 years.

Most Chinese born in the 1980s are the only child in their families. “Being brought up in a well-off environment and now becoming parents, they value early education and are willing to purchase products and services for their kids, starting from a very young age,”Liu said.

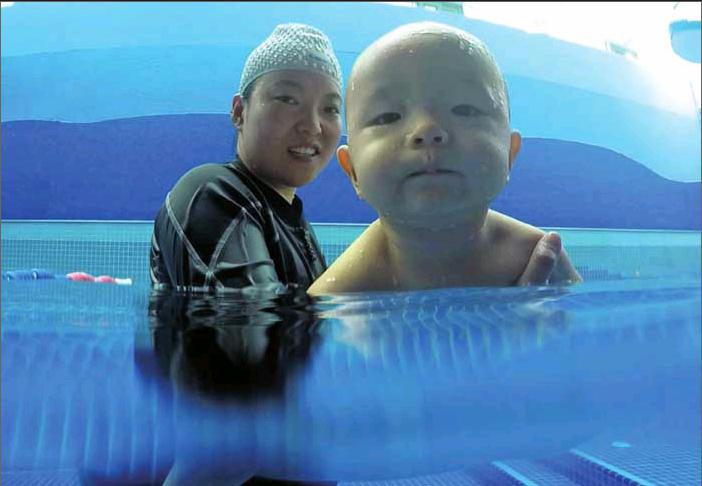

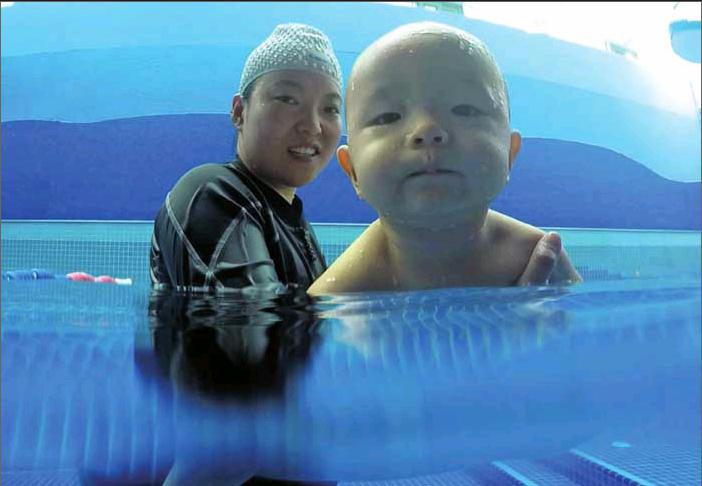

Lu Yao, 30, perfectly fi ts this trend. The young mother purchased a membership to an early education club in Beijing for her one-year-old son, in addition to subscribing to related books and videos. Despite being busy with her work, she manages to take her son to gym and music classes twice a week.

“The books and videos help me better interact with my kid and develop his intelligence. The enrichment activities and programs in the early education club are enjoyable and rewarding,” Lu said.

At an annual cost of 1,400 yuan ($203), the books and videos are delivered to her home on a monthly basis. Her package of 72 gym and music classes costs about 16,000 yuan ($2,320).

As the needs and interests of each child vary, so do the early education programs. Instead of gym and music, Beijing resident Zhang Juan chose painting and dancing classes for her four-year-old girl. “I spent at least 10,000 yuan ($1,450) on my girls extracurricular activities last year,” she said.

A hot venture

Chinas revised Law on the Promotion of Privately Run Schools, to be implemented in September this year, will lay a stronger legal foundation for further development of the private education sector. It will allow education companies to choose whether they will operate as non-profi t entities or as commercial businesses. The prohibition on the listing of commercial education businesses will also be lifted.

According to the revised law, private schools offering nine-year compulsory education must be non-profit and under strict supervision. “Other parts of the educational system like preschool, senior high school and higher education will face no risk of policy uncertainty. We are expecting a healthier ecosystem in the education industry, with more and more investments coming into this sector,” noted Gao Shuai, a lawyer at Beijing Dacheng Law Firm.

The improved legal environment is already producing results. Besides startups opening franchise outlets of preschool education services, non-education companies listed on the A-share market are now entering the sector by acquiring established early education businesses.

Vtron Group Co. Ltd., a video wall solutions provider, acquired Hoing Education and its 1,192 kindergartens in early 2015 for 520 million yuan ($75.3 million). Since then, providing operating solutions to kindergartens has been a fl agship activity of Vtron.

Vtrons venture in the sector paid off handsomely. According to the companys 2016 annual report, its total revenue amounted to 1.05 billion yuan ($152 million), a year-on-year increase of 12.11 percent. A total of 37.5 percent of the revenue came from its newly purchased preschool education business.

In contrast to Vtrons focus on physical kindergarten facilities, Hodgen, a manufacturer of intelligent household appliances based in east Chinas Jiangsu Province, is taking a strong stance in the sector by offering online education services.

“Against the backdrop of the economic‘new normal and the impact of the ceiling effect on manufacturing companies growth, more and more of them are seeking new growth momentum. The education sector, with great prospects and a favorable policy environment, is a good choice under the current circumstances,” noted Liu.

More oversight needed

As is the case with other emerging sectors, the early education industry will have to deal with many issues, not the least of which is quality control, according to insiders. As of now, companies providing preschool education services have no mature teaching system or assessment standard.

“Many early education clubs or centers have no fixed and consistent curriculum or stable teaching facilities to guarantee the quality of their services,” noted Yuan Ailing, an expert with the School of Education at South China Normal University in Guangdong Province.

“There should be better market access standards and stricter supervision on such businesses,” she said.

Experts believe the market should play its due role in this regard, as the sector remains profi t-driven.

“Meanwhile, the government can set requirements for businesses entering this sector and guarantee that consumers have legal channels to safeguard their rights in case of fraud or disputes,” said Xiong Bingqi, Deputy Director of the 21st Century Education Research Institute, a public education think tank.