Protecting A Paradise

2017-07-19ByWangHairong

By+Wang+Hairong

If you are looking for an idyllic sanctuary to escape from the hustle and bustle of daily life, Zhaji Village in Jingxian County in Anhui Province is the right place. Tucked away in gently rolling hills, Zhaji is built along three streams gurgling through it. Strolling along river banks lined with whitewashed homes with black—tile roofs iconic to the area, one cannot help being infatuated with its simple and natural beauty.

A dream land

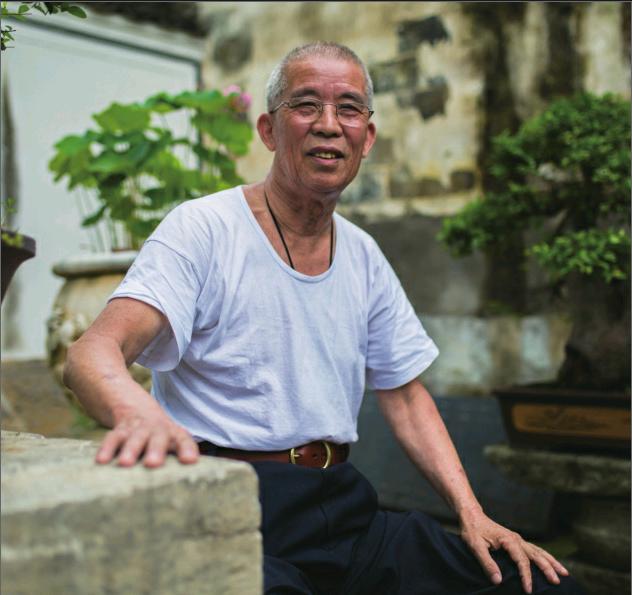

“Zhaji is a waterfront town distinct from other typical ones in southern China. It is a water town among the hills, and a hilly town by the water,” Zha Congjian, an official with Jingxians Culture and Tourism Committee, told Beijing Review. In his eyes, Jingxian has exactly the right blend of water and mountains.

Zha grew up in the village, where most of the residents bear this surname. Talking about his hometown, he is ebullient, revealing his affection for the place.

At the entrance of this picturesque village, two gigantic trees stand proudly, one a 200-plus-year-old laurel tree, and the other a chestnut tree believed to be more than 500 years old. Some villagers chat idly on benches beneath tree canopies.

Pristine bucolic scenes are drawing photographs. A buffalo, accompanied by a cattle egret, crouches in a nearby field. Nonchalant cats and dogs follow visitors wandering in narrow lanes. Ducks are grooming themselves on a patch of sandy shoal at the bottom of a stream while chickens are picking grain on the banks. Downstream, a woman is doing laundry in the river, while a man is rinsing bowls and plates further upstream.

The villages streams are lucid and winding. Zha said the curvature of the rivers yields great aesthetic appeal as the view unfolds slowly before the eye. At the same time, mountain torrents are tamed and slowed down as they enter the village. In addition, these curves have increased the total length of the rivers crisscrossing the village, so that more households can have close access to water.

The village also impresses visitors with its historical architecture. It is said that it had 108 temples, 108 ancestral shrines and 108 bridges at its historical prime. Local culture was once under strong Buddhist influence. Now, the village still has many houses built during the Yuan (1271-1368), the Ming(1368-1644) and the Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

The style of Zhajis ancient buildings differs from those in Beijing which are not as fl oridly painted and use less carvings. “Only parts of the windows and pillars are carved,”Zha said. “It is like a painter who leaves some blanks rather than filling up the entire canvass.”

Some visitors are so enchanted by the village that they settle down there, including Chinese painters as well as foreigners, Zha said.

Protection amid development

Although mountains embracing the village have sheltered it from social upheavals in ancient times, many historical buildings there barely survived the “cultural revolution” (1966-76), a period during which many historical buildings were dismantled.

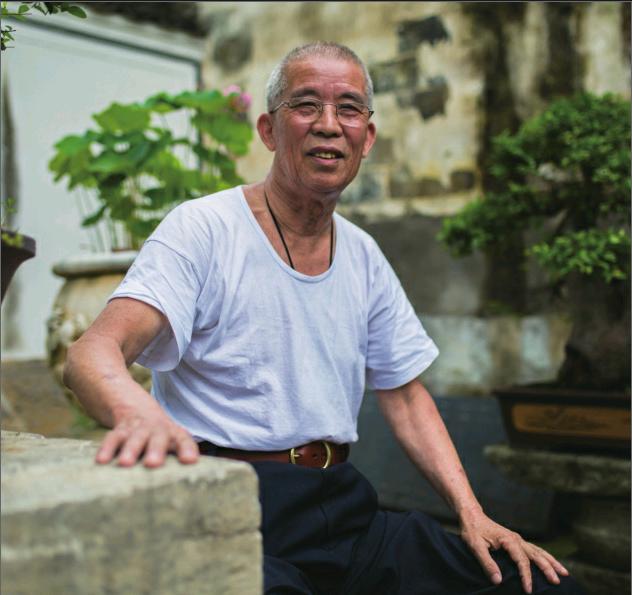

After the “cultural revolution,” historical buildings were still under threat of being torn down. When a ramshackle ancestral shrine was toppled and the remains sold, Wang Zhaolan, the then village head, realized that they must do something to protect ancient buildings.

In the 1990s, a voluntary cultural relic preservation society was set up in the village. Wang recalled that 27 persons, including retired village cadres, attended its inaugural meeting, where he was elected as its chairman. The members chipped in with money for relic protection, and reported relic thefts to police so that some stolen items were retrieved.

Historical buildings were then put under the protection of the county and provincial governments, and in 2001, some were put under national protection, Zha said. The government began to repair and restore historical buildings.

In 2005, the Jingxian Government set up an offi ce to protect and develop ancient residential buildings in Zhaji, which was later known as Zhaji Scenic Area Management Committee, according to Zha.

The county government decided to develop tourism in Zhaji, selling tickets to visitors. Currently, the tourist bureau is jointly run by the county government and a travel company.

In recent years, tourism has become the backbone of the village economy. According to Zha, every year there are 400,000 visits to the village, generating a total income of 5 million yuan ($732,000). Currently, a visitor is charged 80 yuan ($11.7) for a ticket.

The village has about 3,000 residents, and approximately one third of them work in the tourism industry, Zha said. They operate rural guesthouses, inns and shops and provide other travel services. There are more than 100 shops and guesthouses in the village, with over 2,000 beds.

Zha Hongwei, a man in his late 40s, operates the Xiangpu Inn. A native of the village, he first farmed land for a living, and then left his hometown to work in the more economically developed Jiangsu Province. He returned to the village in 2009 and opened the inn in 2012.

“As tourism developed in Zhaji, I saw business opportunities back in my hometown, so I returned home. Besides, I wanted to reunite with my family,” he told Beijing Review. He renovated his own house with his savings and money borrowed from relatives and opened the inn with a dozen rooms.“Now, the inn fetches an annual income of approximately 200,000 yuan ($29,263), which is much better than income from the fields,” he said. He expects more guests in the future as Jingxians county seat is now accessible by a highway that runs from Beijing to Huangshan Mountain, a famous tourist destination not far from Zhaji.

Other residents have also benefi ted from tourism development. Zha Congjian said that ticket revenues pay for the villagers health insurance and contribute to infrastructure improvement in the village, such as road maintenance and garbage collection.

“In the past, villagers had a low income whereas now, they are admired by people in nearby villages [for being richer],” he said.

While residents get richer, they want better living conditions and problems ensue. Some villagers have built unauthorized structures that are not compatible with the style of the ancient village, said Zha Congjian.

To reconcile the villagers need for modern amenities with relic protection, he has suggested that a new area be set aside outside the ancient village, where new houses compatible with the style of old village can be built; residents still living in the old houses can have the interiors redesigned without altering the exterior.

Tourism has increased the overall income, but without proper management, the environment can be damaged. In Zhaji, this is not the case. The water is clear, streets are clean and trees are abundant.

The villages relic protection society has mobilized villagers to clean up and dredge rivers. A lady in her 80s could not contribute any physical labor, so she sold chicken eggs and donated her earnings, Wang said.

Wang recalled that several years ago, torrential rain flooded the village, leaving bridges damaged and rivers clogged with silt. Villagers were mobilized to clean up and repair the bridges.

Garbage bins are seen on the streets. Wang said solid waste is collected and shipped to the county seat for disposal, waste water from guesthouses and restaurants is treated, and facilities have been installed in rivers to filter out heavy metals. The village also forbids residents to chop down trees without permission.

“Now Zhaji has a profusion of vegetation, and trees are not chopped down illegally. No rare trees have been stolen in recent years,”Zha Congjian confi rmed.

“Tourism development can also promote the protection of natural and cultural environment,” he said, “when residents realize that natural and cultural environment can be translated into economic value through tourism, they are keen to protect the environment.”