Physical activity during pregnancy and the role of theory in promoting positive behavior change:A systematic review

2017-07-05ErikaThompsonCherylVamosEllenDaley

Erika L.Thompson*,Cheryl A.Vamos,Ellen M.Daley

Department of Community and Family Health,University of South Florida,Tampa,fl33612,USA

Physical activity during pregnancy and the role of theory in promoting positive behavior change:A systematic review

Erika L.Thompson*,Cheryl A.Vamos,Ellen M.Daley

Department of Community and Family Health,University of South Florida,Tampa,fl33612,USA

Background:Physical activity(PA)during pregnancy provides physical and psychological bene fits for mother and child.U.S.guidelines recommend≥30 min of moderate exercise for healthy pregnant women most days of the week;however,most women do not meet these recommendations.Theory assists in identifying salient determinants of health behavior to guide health promotion interventions;however,the application of theory to examine PA among pregnant women has not been examined cohesively among multiple levels of in fluence(e.g., intrapersonal,interpersonal,neighborhood/environmental,and organizational/political).Subsequently,this systematic review aims to identify and evaluate the use of health behavior theory in studies that examine PA during pregnancy.

Methods:Articles published before July 2014 were obtained from PubMed and Web of Science.Inclusion criteria applied were:(1)empiricallybased;(2)peer-reviewed;(3)measured factors related to PA;(4)comprised a pregnant sample;and(5)applied theory.Fourteen studies were included.Each study’s application of theory and theoretical constructs were evaluated.

Results:Various theories were utilized to explain and predict PA during pregnancy;yet,the majority of these studies only focused on intrapersonal level determinants.Five theoretical frameworks were applied across the studies—all but one at the intrapersonal level.Few determinants identi fied were from the interpersonal,neighborhood/environmental,or organizational/political levels.

Conclusion:This systematic review synthesized the literature on theoretical constructs related to PA during pregnancy.Interpersonal,community, and societal levels remain understudied.Future research should employ theory-driven multi-level determinants of PA to re flect the interacting factors in fluencing PA during this critical period in the life course.

©2017 Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Physical activity;Pregnancy;Theory

1.Introduction

Physical activity(PA)during pregnancy has been proposed to have numerous health bene fits across the life course.Being physically active during pregnancy is associated with reduced risk of adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes,including preeclampsia,gestational diabetes,and preterm birth.1,2PA during pregnancy can also have implications for psychological health, including overall mood and self-esteem.3Moreover,PA can support healthy gestational weight gain,4particularly since the amount of excessive weight gain during pregnancy is a signi ficant predictor of postpartum weight retention.5Therefore, having adequate levels of PA during pregnancy can have longterm,positive impacts for women’s health.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)has recommended that pregnant women should engage in moderate exercise for 30 min a day on most days of the week,with the exception of women with compromising health conditions(e.g.,pre-eclampsia).6Despite these recommendations,only 13.8%of pregnant women in the US are physically active.7Furthermore,women are less likely to sustain PA as the pregnancy progresses into later trimesters8and during the transition to parenthood.9The salience of this issue is ampli fied given that pregnancy is identi fied as a“teachable moment”in which women are amenable to change behaviors that can bene fit their health and their baby’s health.10

In order to promote PA during pregnancy,theory serves as a powerfulmethodologicaltoolforhealth behaviorchange.Theory can explain or predict a phenomenon and is extensively used in health behavior research.11Previous research on predictors of PA during pregnancy has primarily focused on demographic,non-modi fiable correlates of the behavior.8Yet,there is a need to understand the potentially modi fiable factors for PA during this unique period that is sensitive to change.Moreover,it is well known that health behavior is in fluenced by multiple factors across the socio-ecological levels.12For example,intrapersonal (e.g.,knowledge,attitudes,beliefs),interpersonal(e.g.,social support),neighborhood/environmental(e.g.,side walk availability),and organizational/political(e.g.,workplace policies)factors can be interacting forces that in fluence PA patterns.

A firm understanding ofthe multi-level,theory-based factors for PA during pregnancy is critical to inform future health promotion intervention development.13However,aprevioussystematic review examined the use of behavioral change techniques for PAinterventions during pregnancy and found thatout of the 14 studies included in the review,only 2 were grounded using theoretical frameworks.While behavioral change techniques(e.g.,goal setting,feedback,repetition)can provide successfuloutcomes,the use oftheory fordeveloping interventions directly maps needs and assets to theory-based intervention components and improves generalizability of findings.14Therefore,itisnecessary to understand the currentliterature regarding the theory-based factors that in fluence PA during pregnancy in orderto inform future intervention development.The purpose of this study was to systematically review and evaluate the use of health behavior theory in observational studies that examine PA among pregnant women.

2.Materials and methods

Methods of this systematic review were speci fied prior to commencement in a study protocol.The protocol referenced Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis(PRISMA)guidelines15and recommendations for integrative reviews(i.e.,reviews of quantitative and qualitative research).16Articles were systematically selected from a search of PubMed and Web of Science databases,during a date range of database inception until July 2014.Search terms were organized into general categories of pregnancy(e.g.,pregnan*, gestation*,pregnant women),PA(e.g.,leisure-time activity, physical activity,exercise, fitness,motor activity),and theory (e.g.,theory,conceptual framework).The search strategy in each database used the Boolean term of“AND”for inclusion of each general category,and the Boolean term of“OR”for inclusion of each search term within the category.

Inclusion criteria applied were:(1)empirically-based; (2)published in a peer-reviewed journal;(3)measured factors related to PA during pregnancy;(4)comprised a pregnant sample;and(5)used a health behavior theory.Studies were excluded if they tested an intervention since this review focused on observational designs only,and not experimentally impacted theoretical determinants.Additionally,studies were excluded if only a published abstract was available since not enough data were available for abstraction.

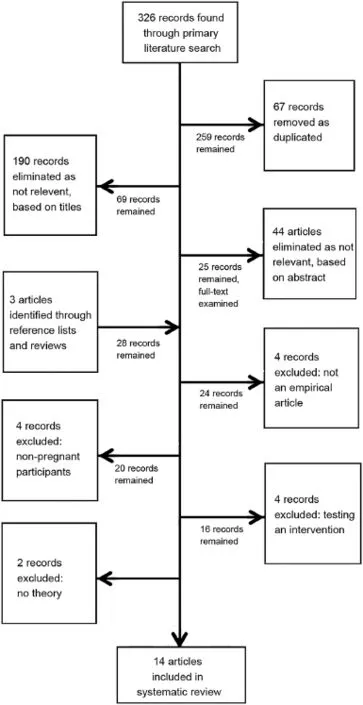

Fig.1.Search strategy for systematic review of theory-based determinants of physical activity during pregnancy.

Fig.1 presents the search process for this systematic review. The primary search of the literature identi fied 326 articles. After removing 67 duplicates,259 articles remained.Articles were then screened based on titles and relevance to the research topic;this removed 190 articles.Next,articles were assessed based on the abstract to determine the relevance to the research topic;this resulted in 25 articles remaining.Three additional articles were added to the search strategy from hand-searching reference lists from the remaining articles.Twenty-eight fulltext articles were examined to determine eligibility based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.Four articles were excluded for not providing details of an empirical study(i.e.,only a published abstract was available),4 articles were excluded for not including pregnant participants,4 articles were excluded for testing or describing an intervention,and 2 articles were excluded for not measuring theory-based constructs for PA.

Each article had the following information abstracted for review:publication year,authors,article title,journal title,research questions and purpose,hypotheses,theory used,study design,sample description,trimester,sample size,methodology,measurement of PA behavior,instrument(s)used,analysis, and key findings related to theoretical constructs.Data were abstracted by the first author of the manuscript.

The primary purpose of this article was to conduct a qualitative synthesis of the theory-based constructs associated with PA during pregnancy.All theoretical constructs and findings from each article were abstracted and grouped by the levels of the Socio-ecological Model(i.e.,intrapersonal,interpersonal, neighborhood/environmental,and organizational/policy).12This allowed for identi fication of themes at varying levels of impact.According to PRISMA guidelines,it is recommended that reviews conduct a quality assessment of the methodology of included studies.15However,given that this review integrates both qualitative and quantitative observational methodologies, this prohibits a single,standardized evaluation tool for quality assessment.16,17

3.Results

Fourteen articles were included in this systematic review that examined theoretical determinants of PA during pregnancy. However,4 of the included articles comprised 1 longitudinal study using 1 theoretical framework;therefore,this was reported as 1 empirical study.18–21Articles included in the review were published between 2003 and 2014,despite searching for articles prior to these dates.

Table 1 presents study methodological characteristics for each article.Studies included several countries of origin, including the US,UK,Australia,Canada,Portugal,and South Africa.Three studies selected participants based upon prepregnancy weight category in order to elicit determinants among overweight and obese pregnant women.22–24There was also variability in study inclusion criteria for which trimester women were sampled.

Thisreview included studiesthatutilized both qualitative and quantitative methodologies to collect data on factors related to PA during pregnancy.Surveys were the most frequently utilized data gathering tool;18–21,23,25–29however,qualitative techniques such as focus groups,30,31open-ended interview questions,30and semi-structured interviews22,24were also employed.

The majority of studies had a measure of intensity or frequency of PA during pregnancy,yet a few studies did not measure this.23,24,30,31Other studies relied on validated instruments,such as the Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire,20,21,27the Modi fiable Activity Questionnaire,25or the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire.28The remaining studies assessed moderate or vigorous PAs conducted days per week.18,19,22,26All behavior measurements were based on selfreport of activity,except in 1 study.Santos et al.29objectively measured pregnant women’s compliance with recommended guidelines for PA using an accelerometer over a 7-day period.

3.1.Theories

The majority of studies utilized intrapersonal level theories to identify factors associated with PA during pregnancy (Table 2).Intrapersonal level theories applied to PA during pregnancy included the Theory of Planned Behavior,18–21,24,28,31the Health Belief Model,23,26Organismic Integration Theory,27and the Self-Ef ficacy construct from the Social Cognitive Model.25While 3 studies applied the Socio-ecological Model, the findings were primarily focused on intrapersonal determinants,rather than higher-levels of in fluence.22,29,30

3.2.Factors by Socio-ecological Model level

3.2.1.Intrapersonal

The majority of health behavior theories were derived from the intrapersonal level,and thus a substantial portion of the factors in this review was identi fied at this level.Many studies identi fied the perceived bene fits and barriers to PA.Perceived bene fits included improved health,22,23,31feeling better/good,23postpartum weight loss22and improved health for the baby.26

However,the major focus in these studies was on barriers to PA.Pregnant women were more likely to have pregnantspeci fic barriers compared to a non-pregnant sample.28Overall,intrapersonal barriers were dichotomized into 2 categories:health related and non-health related.Examples of health related barriers include physical limitations,25health conditions,23,24tiredness,22,23,25,30,31and pain.22,28–31Non-health related barriers were related to psychosocial attitudes toward PA,speci fically lack of motivation24,25,29–31or lack of self-con fidence.24,31Compounding these barriers was the reported lack of time to engage in PA.23–25,29–31Additionally, women reported a lack of knowledge regarding what types of activity they should be engaged in during pregnancy.23,28,30Perceived barriers may also change as a woman progresses in her pregnancy.25Furthermore,relative to other behavioral changes that can impact gestational weight gain,exercise was referred to as more dif ficult to change compared to diet.23

Intention to perform PA was a signi ficant predictor across all trimesters,18,19,21with the exception of predicting behavior within Trimester 1.20However,intention was a relatively weak predictor longitudinally in pregnancy.21In these studies utilizing the Theory of Planned Behavior,attitudes about PA were also measured(e.g.,useful,pleasant,enjoyable);however,it was not a signi ficant predictor of behavior.Rather attitudes for PA were only signi ficant predictors for intention for behavior in 3 studies.18,20,21

Self-ef ficacy was a signi ficant construct for PA during pregnancy.Pregnant women viewed exercise as under their control,planning to be active,and being able to exercise even on busy days.23An additional study examined self-ef ficacy as 2 separate constructs:barrier self-ef ficacy(i.e.,con fidence in overcoming barriers to exercise)and exercise self-ef ficacy (i.e.,con fidence in the ability to exercise).Cramp and Bray25reported that exercise self-ef ficacy is a more proximal predictor of PA;however,if substantial barriers exist then barrier selfef ficacy is a more dominant predictor.

Finally,identi fied regulation was a signi ficant predictor when applying the Organismic Integration Theory.This construct is a source of extrinsic motivation and represents a person’s outcome expectancies related to the behavior.27

Table 1 Descriptive methodological characteristics by author name of articles selected for the systematic review.

Table 2 (continued)

3.2.2.Interpersonal

There was a paucity of interpersonal theories applied to PA during pregnancy;however,interpersonal factors did emerge. While normative beliefs or subjective norms are derived from an intrapersonal level,for the purposes of this review it is examined at the interpersonal level as it is describing persons identi fied as valuable for informational and motivational support to PA during pregnancy.Healthcare providers were viewed as important sources of support for PA during pregnancy.23,28,31However,provider advice was reported as conflicting with information from family members that advised women to rest during pregnancy.24,31Many studies identi fied the bene fit of family and friends support,as well as childcare.22,23,25,30Furthermore,2 studies reported the need for pregnancy-speci fic exercise companionship.29,31Despite the salience of identifying sources of social support for PA during pregnancy,subjective norms had limited predictive value on PA intention during pregnancy.18,21

3.2.3.Neighborhood/environmental

There is a dearth of theory-based factors from a neighborhood or environmental perspective.The studies that examined neighborhood and environmental factors were qualitative or descriptive in design;as a result,there were no reported measures of how these factors impacted PA levels.Weather was a commonly reported barrier to PA.23–25,30For example,women reported that changes in the season or the temperature being too hot or too cold made it dif ficult to exercise outside.23,30Neighborhood characteristics were also reported as barriers,including safety concerns and distance/access to facilities.22–24,29,31Potential facilitators for PA were described by women as the existence of PA education programs for pregnant women in their community,speci fically group exercise programs.31

3.2.4.Policy/organizational

Policy and organizational factors were the least likely cited factors to PA during pregnancy.30Similar to neighborhood/ environmental factors,the policy and organizational factors were the result of elicitation or descriptive studies,rather than prediction studies.These determinants were most commonly conceptualized as barriers and included lack of childcare,work con flicts,and cost.23–25,30,31For example,work con flicts were perceived as a barrier to PA and were attributed to the lack of time and low energy levels as a result of working.24Childcare responsibilities were reported as a barrier across trimesters more often for multiparous women compared to women without children.25

4.Discussion

This systematic review synthesized the results of 14 empirical articles that applied theoretical frameworks to examine PA during pregnancy across multiple levels of in fluence.Themajority of the studies focused on factors at the intrapersonal level due to the selection of theoretical frameworks.The only exception was the use of the Socio-ecological Model itself as a guiding framework in 3 studies.22,29,30Therefore,studies excluded more distal factors that may limit or facilitate PA,and thus there is a need to further examine the interpersonal,community,organizational,and political in fluences that impact the more proximal intrapersonal factors of PA behavior.Considering distal level factors is consistent with the Institute of Medicine report that indicates the signi ficant impact of the built environment in facilitating or prohibiting PA,32as well as other PA reviews among adults emphasizing the importance of multilevel frameworks.33,34

The majority of factors identi fied at the intrapersonal level were barrier focused.These barriers were related to health issues while being pregnant,as well as non-health related issues,such as motivation or con fidence.These unique barriers reported during pregnancy should be the focus of health education components to find accommodations for exercise that address these speci fic issues.Moreover,integrating these findings on barriers with those regarding self-ef ficacy to overcome the barriers to exercise23,25may improve intervention development.Additionally,developing health messages that align with the perceived bene fits of PA during pregnancy,such as improved health for baby or postpartum weight loss,22,26may also support behavior change.

At the interpersonal level, findings related to family support corroborate previous correlational data that report marriage as a positive,signi ficant predictor for PA during pregnancy.8,26The multi-faceted layers of social support may impact women attempting to engage in PA during pregnancy.For example, instrumental support may assist women in overcoming barriers to childcare or work-related con flicts.Informational and appraisal support are required to inform women of the bene fits of PA during pregnancy and how it can impact maternal and child health.35

Additionally,healthcare providers were identi fied as important sources for information regarding PA.23,28,31Healthcare providers have an important role,which includes clarifying the bene fits and emphasizing the importance of PA during pregnancy.This is especially important as pregnant women may receive con flicting information from family members and healthcare providers;both considered trusted sources of health information.24,31While previous research has indicated that healthcare providers often have positive beliefs regarding PA during pregnancy,not all providers reported disseminating current ACOG recommendations for this behavior to their patients.36,37Thus,there is a need to further engage these providers to communicate and advise women with regard to thecurrentnational PA guidelines in a clear and patient-centered manner.38

Additionally,this systematic review revealed that there is variability in which theory-based factors were signi ficant at each trimester.For example,in the series of papers presented by Hausenblas and Downs using the same sample of women at different time points,constructs from the Theory of Planned Behavior,speci fically intention and perceived behavioral control,alternated in signi ficance for different trimesters.18–20Therefore,certain behavioral constructs may be more in fluential during different stages of pregnancy,which is important to recognize when designing future health promotion interventions for this target population.

This systematic review has revealed overlap in some theoretical constructs.For example,barrier self-ef ficacy and perceived behavioral control can intersect,both re flect the underlying phenomenon of personal agency.20,21,25Interestingly,both of these constructs were only signi ficant predictors during the early phases of pregnancy.This highlights the need to consolidate and synthesize the theory-based literature for any health behavior in order to identify these types of overlap in underlying constructs that may use different labels or language.

There was an overall paucity of diversity in the samples among the studies included that were conducted in the USA. The majority of studies focused on homogenous samples of primarily Caucasian women;few had diverse participants, such as African Americans.22,30Previous epidemiological studies have identi fied racial/ethnic differences in the level of PAduring pregnancy.7,39In addition,the diversity ofthe samples with regards to other socio-demographics needs to be further explored.For example,previous research has found differences in PA levels by marital status,education,health status,and household income.40Moreover,therewasalack ofheterogeneity for body size(i.e.,normal weight,overweight,and obese)prior to pregnancy with the exception of 3 studies.22–24Similarly, pre-pregnancy body size impactsthe levelofPA,and potentially the determinants of PA during pregnancy.41,42Future research should examine theory-based predictors of PA among diverse samples of participants and consider potential mediating variables,such as pre-pregnancy body size.

Several limitations should be acknowledged.This review only included published,peer-review literature;therefore it may be subject to potential publication bias.Additionally,the review was limited to a qualitative synthesize only since the includedstudies lacked consistency in terms of the PA and determinants measures used,limiting the ability to compare measures of effect across studies.This field of investigation would bene fit from standardized procedures to assess PA in the pregnant population.Finally,this review did not include an evaluation of the quality of the studies.This is a limitation of reviews that integrate both qualitative and quantitative methodologies,which prohibits a single,standardized quality assessment across studies. However,the authors argue that it is necessary to consider rigorous,qualitative methodologies in systematic reviews of the literature,as this adds to the scope of the findings related to the research topic.In this review,the examination of the theory-based literature for PA during pregnancy was enriched by including qualitative study designs.

Although health promotion interventions have targeted PA during pregnancy in order to promote adequate gestational weight gain,limited improvements have been observed.43Furthermore,there has been a dearth of theory used to inform intervention design and those that were theory-informed had minimal effects for PA during pregnancy to prevent excessive gestational weight gain.44Nonetheless,evidence has shown that using theory to design interventions can lead to improved effects compared to those without theory.11For instance,studies applying theoretical constructs to improve PA levels in adult, non-pregnant populations have been successful.45Intervention mapping is a potential tool for future research to integrate the findings on the salient theoretical determinants that impact PA during pregnancy in this review to promote PA behavior change during pregnancy through the development of theory-based and evidence-informed interventions.46

Additionally,development of multi-level interventions are the most effective in changing behaviors compared to those that only target individual level determinants.11Thus,the lack of improvement in outcomes related to PA during pregnancy in previous research may be the result of minimal applications of health behavior theory at multiple levels of in fluence to the intervention design.For example,pregnant women interact with healthcare providers throughout their pregnancy and are regarded as a trusted source of information.Therefore,these agents should be targeted as well in the delivery of health interventions for pregnant women.10Additional research on the knowledge,attitudes,and beliefs regarding provider adherence to ACOG guidelines for PA during pregnancy recommendations to pregnant patients is warranted.

Finally,this systematic review identi fied areas in the literature that require additional research.First,this review included findings from relatively homogenous samples.Future research should be dedicated to elucidating theory-based predictors of PA within the context of unique cultures or demographic factors.The epidemiological research indicates that rates of PA during pregnancy vary by demographic factors,such as race/ ethnicity,education status,and income.7,39,40These findings may reveal distinctive factors that would contribute to improving PA during pregnancy.Secondly,the factors identi fied in this systematic review at the intrapersonal level were primarily de ficit or barrier focused.While it is necessary to understand what prohibits PA during pregnancy,additional research is required to elucidate the facilitators or assets to PA during this unique period.These facilitators may contribute to improved uptake of future PA interventions targeted toward this population.

5.Conclusion

Theoretical constructs are useful tools for examining PA, especially in a unique population,such as pregnant women. Future work should implement multi-level,theory-based determinants of health behavior into health promotion interventionsaimed atincreasing PA during thisperiod,which isnotably amenableto behaviorchange.Ultimately,improving levelsofPA during pregnancy has the potential to have positive health outcomes for women across the life course.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Elizabeth Lockhart for her feedback throughout the preparation of this manuscript.

Authors’contributions

ELT conceived of the study and conducted the systematic review process;CAV and EMD also conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination.All authors drafted the manuscript,read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agreed with the order of presentation of authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

1.Gavard JA,Artal R.Effect of exercise on pregnancy outcome.Clin Obstet Gynecol2008;51:467–80.

2.Lewis B,Avery M,Jennings E,Sherwood N,Martinson B,Crain AL.The effect of exercise during pregnancy on maternal outcomes:practical implications for practice.Am J Lifestyle Med2008;2:441–55.

3.Poudevigne MS,O’Connor PJ.A review of physical activity patterns in pregnant women and their relationship to psychological health.Sports Med2006;36:19–38.

4.Pivarnik JM,Chambliss HO,Clapp JF,Dugan SA,Hatch MC,Lovelady CA,et al.Impact of physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum on chronic disease risk.Med Sci Sports Exerc2006;38:989–1006.

5.Nehring I,Schmoll S,Beyerlein A,Hauner H,von Kries R.Gestational weight gain and long-term postpartum weight retention:a meta-analysis.Am J Clin Nutr2011;94:1225–31.

6.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.Exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period.ACOG Committee Opinion No.267.Obstet Gynecol2002;99:171–3.Reaf firmed 2009.

7.Evenson KR,Wen F.National trends in self-reported physical activity and sedentary behaviors among pregnant women:NHANES 1999–2006.Prev Med2010;50:123–8.

8.Gaston A,Cramp A.Exercise during pregnancy:a review of patterns and determinants.J Sci Med Sport2011;14:299–305.

9.Allender S,Hutchinson L,Foster C.Life-change events and participation in physical activity:a systematic review.Health Promot Int2008;23: 160–72.

10.Phelan S.Pregnancy:a“teachable moment”for weight control and obesity prevention.Am J Obstet Gynecol2010;202:135.e131–8.

11.Glanz K,Rimer BK,Viswanath K.The scope of health behavior and health education.In:Glanz K,Rimer BK,Viswanath K,editors.Health behavior and health education:theory,research,and practice.Vol.4.San Francisco, CA:John Wiley&Sons,Inc.;2008.

12.McLeroy KR,Bibeau D,Steckler A,Glanz K.An ecological perspective on health promotion programs.Health Educ Q1988;15:351–77.

13.Downs DS,Chasan-Taber L,Evenson KR,Leiferman J,Yeo S.Physical activity and pregnancy:past and present evidence and future recommendations.Res Q Exerc Sport2012;83:485–502.

14.Currie S,Sinclair M,Murphy MH,Madden E,Dunwoody L,Liddle D. Reducing the decline in physical activity during pregnancy:a systematic review of behaviour change interventions.PLoS One2013;8:e66385. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066385

15.Moher D,Liberati A,Tetzlaff J,Altman DG;PRISMA Group.Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses:the PRISMA statement.Ann Intern Med2009;151:264–9.

16.Whittemore R,Kna flK.The integrative review:updated methodology.J Adv Nurs2005;52:546–53.

17.Sanderson S,Tatt ID,Higgins JP.Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography.Int J Epidemiol2007;36:666–76.

18.Downs DS,Hausenblas HA.Exercising for two:examining pregnant women’s second trimester exercise intention and behavior using the framework of the theory of planned behavior.Womens Health Issues2003;13:222–8.

19.Downs DS,Hausenblas HA.Pregnant women’s third trimester exercise behaviors,body mass index,and pregnancy outcomes.Psychol Health2007;22:545–59.

20.Hausenblas HA,Downs DS.Prospective examination of the Theory of Planned Behavior applied to exercise behavior during women’s first trimester of pregnancy.J Reprod Infant Psychol2004;22:199–210.

21.Hausenblas HA,Downs DS,Giacobbi P,Tuccitto D,Cook B.A multilevel examination of exercise intention and behavior during pregnancy.Soc Sci Med2008;66:2555–61.

22.Goodrich K,Cregger M,Wilcox S,Liu J.A qualitative study of factors affecting pregnancy weight gain in African American women.Matern Child Health J2013;17:432–40.

23.Sui Z,Turnbull DA,Dodd JM.Overweight and obese women’s perceptions about making healthy change during pregnancy:a mixed method study.Matern Child Health J2012;17:1879–87.

24.Weir Z,Bush J,Robson SC,McParlin C,Rankin J,Bell R.Physical activity in pregnancy:a qualitative study of the beliefs of overweight and obese pregnant women.BMC Pregnancy Childbirth2010;10:18.doi:10.1186/ 1471-2393-10-18

25.Cramp AG,Bray SR.A prospective examination of exercise and barrier self-ef ficacy to engage in leisure-time physical activity during pregnancy.Ann Behav Med2009;37:325–34.

26.Evenson KR,Bradley CB.Beliefs about exercise and physical activity among pregnant women.Patient Educ Couns2010;79:124–9.

27.Gaston A,Wilson PM,Mack DE,Elliot S,Prapavessis H.Understanding physical activity behavior and cognitions in pregnant women:an application of self-determination theory.Psychol Sport Exerc2013;14:405–12.

28.Hausenblas HA,Giacobbi P,Cook B,Rhodes R,Cruz A.Prospective examination of pregnant and nonpregnant women’s physical activity beliefs and behaviours.J Reprod Infant Psychol2011;29:308–19.

29.Santos PC,Abreu S,Moreira C,Lopes D,Santos R,Alves O,et al.Impact of compliance with different guidelines on physical activity during pregnancy and perceived barriers to leisure physical activity.J Sports Sci2014;32:1398–408.

30.Evenson KR,Moos MK,Carrier K,Siega-Riz AM.Perceived barriers to physical activity among pregnant women.Matern Child Health J2009;13:364–75.

31.Muzigaba M,Kolbe-Alexander TL,Wong F.The perceived role and in fluencers of physical activity among pregnant women from low socioeconomic status communities in South Africa.J Phys Act Health2013;11:1276–83.

32.National Research Council,Committee on Physical Activity,Land Use, and Institute of Medicine.Does the built environment in fluence physical activity?:examining the evidence.No.282.Transportation Research Board,2005.

33.Humpel N,Owen N,Leslie E.Environmental factors associated with adults’participation in physical activity:a review.Am J Prev Med2002;22:188–99.

34.Sallis JF,Cervero RB,Ascher W,Henderson KA,Kraft MK,Kerr J.An ecological approach to creating active living communities.Annu Rev Public Health2006;27:297–322.

35.House JS.Work stress and social support.Reading,MA:Addison-Wesley Longman,Inc.;1981.

36.Bauer PW,Broman CL,Pivarnik JM.Exercise and pregnancy knowledge among healthcare providers.J Womens Health(Larchmt)2010;19:335–41.

37.Evenson KR,Pompeii LA.Obstetrician practice patterns and recommendations for physical activity during pregnancy.J Womens Health (Larchmt)2010;19:1733–40.

38.Ferrari RM,Siega-Riz AM,Evenson KR,Moos MK,Carrier KS.A qualitative study of women’s perceptions of provider advice about diet and physical activity during pregnancy.Patient Educ Couns2013;91:372–7.

39.Zhang J,Savitz DA.Exercise during pregnancy among US women.Ann Epidemiol1996;6:53–9.

40.Gaston A,Vamos CA.Leisure-time physical activity patterns and correlates among pregnant women in Ontario,Canada.Matern Child Health J2013;17:477–84.

41.Fell DB,Joseph KS,Armson BA,Dodds L.The impact of pregnancy on physical activity level.Matern Child Health J2009;13:597–603.

42.Mottola MF,Campbell MK.Activity patterns during pregnancy.Can J Appl Physiol2003;28:642–53.

43.Campbell F,Johnson M,Messina J,Guillaume L,Goyder E.Behavioural interventions for weight management in pregnancy:a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative data.BMC Public Health2011;11:491. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-491

44.Gardner B,Wardle J,Poston L,Croker H.Changing diet and physical activity to reduce gestational weight gain:a meta-analysis.Obes Rev2011;12:e602–20.

45.Rhodes RE,Pfaef fli LA.Review mediators of physical activity behaviour change among adult non-clinical populations:a review update.Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act2010;7:37–48.

46.Bartholomew LK,Parcel GS,Kok G.Intervention mapping:a process for developing theory-and evidence-based health education programs.Health Educ Behav1998;25:545–63.

vels of in fluence

less attention in the theory-based literature;however,these levels are not without recognition.The tunnel-vision of the literature on intrapersonal level factors related to PA during pregnancy may be attributed to the assumption that organizational,environmental and policy level factors are the same for adults regardless of gravidity.The effect of environmental variables on PA have been studied in the adult population;33however,there is a need to further evaluate these factors in a pregnant population since these women may face unique challenges and barriers due to changing physiology and social circumstances.As mentioned by Muzigaba et al.,31women desired exercise group classes speci fic for pregnant women offered in their communities in order to learn about PA that is appropriate and safe for pregnancy.Additionally,given some of the unique barriers pregnant women with children may face,such as childcare issues,25facilities offering these types of services may be warranted.Moreover,it is necessary to consider these higher levels of in fluence since the degree to which these various environmental and policy factors make it dif ficult to carry out PA may contribute to a woman’s perceived behavioral control.

Received 29 April 2015;revised 16 June 2015;accepted 10 July 2015

Available online 31 August 2015

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

*Corresponding author.

E-mail address:ethomps1@health.usf.edu(E.L.Thompson).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2015.08.001

2095-2546/©2017 Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

杂志排行

Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Endurance exercise and gut microbiota:A review

- Why forefoot striking in minimal shoes might positively change the course of running injuries

- Is changing footstrike pattern bene ficial to runners?

- In fluence of different sports on fat mass and lean mass in growing girls

- Immersible ergocycle prescription as a function of relative exercise intensity

- Self-perceptions and social–emotional classroom engagement following structured physical activity among preschoolers:A feasibility study