A Guardian of Chinese Painting

2017-06-22byYiMei

by+Yi+Mei

Alongside Wu Changshuo, Qi Baishi and Huang Binhong, Pan Tianshou is considered one of Chinas four greatest painting masters of the 20th Century. On May 2, 2017, an exhibition commemorating the 120th birthday of Pan Tianshou opened at the National Art Museum of China, luring the public to take a closer look at the work of this master. The exhibition traces the life of Pan Tianshou as an artist, educator and art theorist through 120 works including his representative paintings, manuscripts and calligraphy.

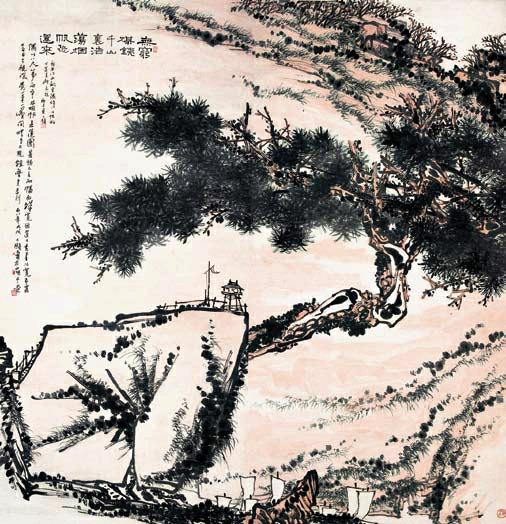

Pans exhibition covers five halls and two corridors of the museum, making it the largest ever held for a single artist at the museum. Located in the center of the first hall is a 1964 work that measures seven meters tall and three meters wide—his largest painting. “Of Chinese painting masters, Pan Tianshou topped in over-sized work,” opined Wu Guanzhong, a renowned contemporary Chinese painter. “His composition is like building a mansion. His large paintings are genuine massive masterpieces.”

Passionate Painter

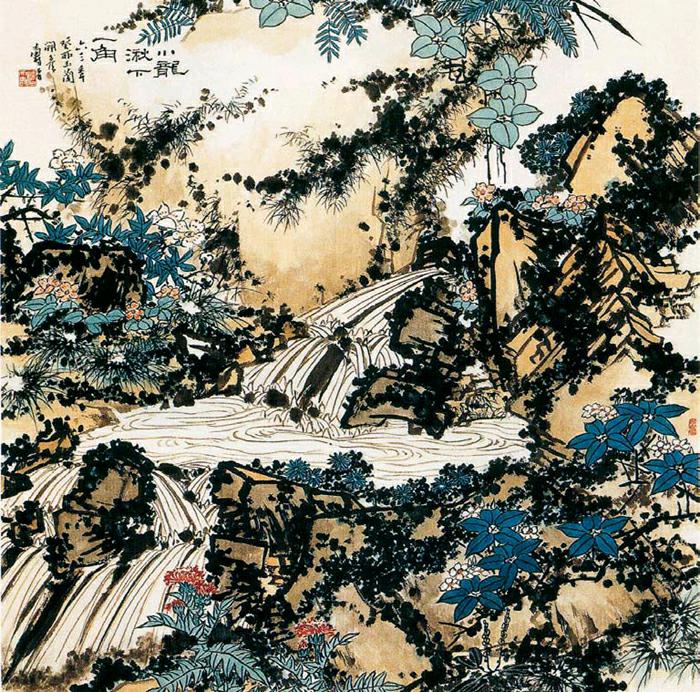

Pan used tough strokes to paint various plants, giving them a towering presentation. In composition, by breaking traditional themes of Chinese landscape and flowerand-bird paintings, Pan depicted scenery more realistically, and created a genre of landscape painting in which the primary components occupy just a corner of the paper. “Pan Tianshous work is so moving because of his profound understanding of the essence of the genre,” remarks Li Jinkun, president of Guangdong Artists Association. “Yet, he developed Chinese painting in his own way, which shook off traditional patterns to some extent.”

The context behind Pans strokes runs even deeper. In the 20th Century, Chinese painting was heavily impacted by Western painting. The New Culture Movement of the 1910s and 1920s called for increased usage of Western artistic techniques to reform traditional Chinese painting. In this context, Western sketch and oil painting became extremely popular in China, and traditional Chinese painting was marginalized. Traditional Chinese painting, a pillar of Chinese culture, seemed to be facing extinction. During this time, Pan advocated that “Chinese painting and Western painting should keep a distance.” He said, “Chinese and Western arts can communicate, which should result in distinction between them rather than shared content and patterns.”

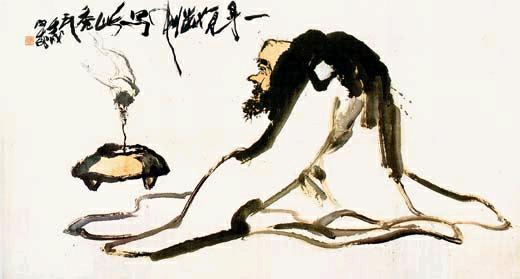

As many artists were trading brushes for pencils, Pan held firm to traditional Chinese painting. One of the seals he used is carved with Chinese characters literally meaning “always overbearing and bold,” in contrast to the ideal aesthetics of Chinese culture. Pan defied traditional culture in favor of a determination to develop, reform and innovate Chinese painting based on traditional rules. His efforts created significant tension that can be seen on his canvases. His choices also evidenced his devotion to safeguard traditional Chinese painting.

Pans confidence in traditional Chinese painting was inspired by his study of the genre, which helped him understand the differences and similarities between Chinese and Western paintings. He believed that both Chinese and Western paintings intend to show the ideas and passion of mankind, but they belong to different artistic systems. Western painting focuses on science, and Chinese painting on philosophy. Scientific rules involving proportion and perspective are not practiced in traditional Chinese painting, which uses calligraphic strokes and ink on a twodimensional surface to convey the artists emotion and thought.

“Mr. Pan did not oppose the fusion of Chinese and Western paintings,” says Chen Yongyi, curator of the Pan Tianshou Museum. “He just opposed blending them arbitrarily. He believed that combining the two genres should be based on academic study and rational thinking. Pan wanted to create an artistic style independent of both ancient Chinese masters and Western painters. He was a pioneer who elevated traditional Chinese painting to a new height, conforming to traditional aesthetics but creating strong visual impacts.”

Devoted Teacher

Although Pan made great achievements in painting, he insisted, “Teaching is my lifelong work, while painting is just my pastime.” Part of the exhibition highlights Pans contributions as a teacher.

The traditional teaching style of Chinese painting followed an apprenticeship model. With the rise of modern schoolbased education, the teaching methods of traditional Chinese painting have changed. Pan devoted his life to designing an independent and comprehensive teaching system for traditional Chinese painting. In the early 20th Century, traditional Chinese painting faced a crisis of survival. The lack of defined teaching mechanisms after the emergence of institutional education brought the art to the brink of extinction.

In 1923, Pan began teaching traditional Chinese painting at the Shanghai Art Academy. In 1928, he was hired as dean of the Chinese Painting Department at the National Art Academy (now the China Academy of Art). His book, The History of Chinese Painting, was the textbook. As China went through ups and downs in the subsequent decades, so did Pans personal status. When Western culture became all the rage, Pans Chinese painting department went quiet. Pan nonchalantly began to collect, purchase, appraise and categorize traditional Chinese paintings from civil collections to enrich his schools collection. His efforts allow todays students at the China Academy of Art to study genuine works directly.

In 1959, Pan was again appointed head of the China Academy of Art, which enabled him to promote his teaching philosophies developed from decades of practice and study. Pan restored the Chinese painting department and proposed subjects like figures, mountains and flowers be taught separately. Courses including Chinese painting study and copying, calligraphy, carving, and poetry were added. Pans creative design for a teaching system for traditional Chinese painting laid a solid foundation for contemporary Chinese traditional arts education.

“Pan was one of the founding fathers of the China Academy of Art and an important educator in Chinese painting and calligraphy,” says Xu Jiang, current president of the China Academy of Art. “He served as president of our school twice. Facing great challenges from Western art, Pan used his broad vision and strong determination to lay the cornerstone for the modern education system of traditional Chinese painting, which has enabled this art form to be passed down and flourish. Pans contribution set a good example for how to make a conscious effort to renew contemporary Chinese art.”