Tibetan Buddhist Heritage in the Forbidden City

2017-05-19ByZHANGXUE&staff

By+ZHANG+XUE+&+staff+reporter+LI+YUAN

THE Forbidden City (aka the Palace Mu- seum) is home to the former imperial palace, official residence of the emperor, his family, and entourage during the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911). The museum now houses 42,000 religious artifacts, 80 percent of which are related to Tibetan Buddhism. This rich collection witnessed the height of Tibetan Buddhism in China.

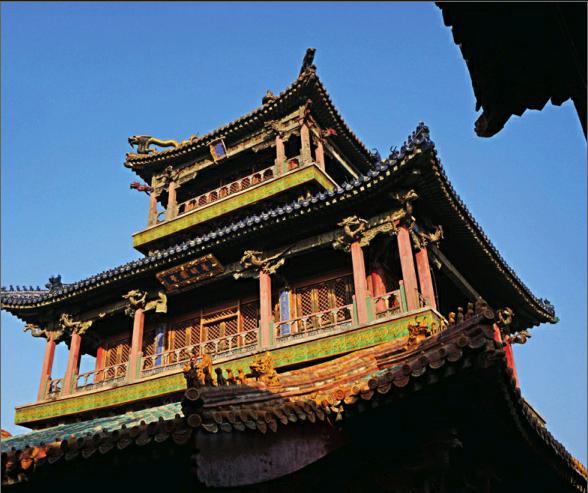

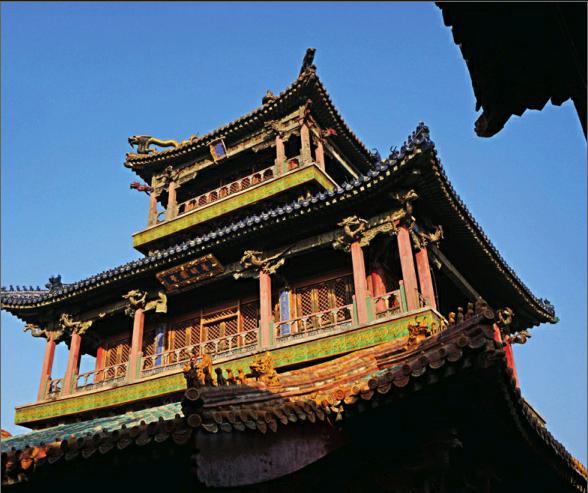

Mysterious Yuhua Pavilion

The Forbidden City is one of the worlds largest and best-preserved wooden buildings. Every day tens of thousands of visitors flock to see its famous halls, but there are some areas of the complex that remain closed to the public and still retain a trace of mystery.

In the northwest corner of the Forbidden City lies Zhongzheng Hall, a cluster of 10 Tibetan Buddhist halls arranged along a north-south axis. These include Baohua Hall, Yuhua Pavilion, and Fanzong Tower. None of these buildings is open to the public.

Yuhua Pavilion was first built during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). In 1749, when Qing Emperor Qianlong decided to renovate the building, the third generation of Changkya Khutuktu, a prominent Tibetan Buddhist and imperial consultant, advised that it be modeled after the Mandala Tower at Tholing Mon-astery in Ngari, western Tibet.

Although it appears to be a three-story building, Yuhua Pavilion actually has four floors and is the only structure in the Imperial Palace complex to combine Han and Tibetan design elements. The Buddha statues on the fourth floor represent four different levels of religious practice.

“The arrangement of historical artifacts in the pavilion remains the same as it was in Emperor Qianlongs reign (1736-1796) and Emperor Jiaqings reign (1796-1820),” noted Luo Wenhua, director of the Institute of Tibetan Buddhist Heritage at the Palace Museum. “The specific date and position of each item is recorded in the museums files,” he said.

Warm winter sunshine filters through the huge red doors onto the rosewood Buddhist pagoda on the ground floor of Yuhua Pavilion. Above the door hangs a tablet with an inscription by Emperor Qianlong.

According to Luo Wenhua, inside the rosewood pagoda are Buddha statues presented as tributes to the emperors by generations of Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama. The pavilion also houses enamel mandalas of the three most important images of Buddha in Tantric Buddhism, as well as many gold and copper Buddha statues, instruments used in rituals, miniature porcelain pagodas and Thangka paintings. While some of these treasures were sourced from Tibet, India, and Nepal by Tibetan and Mongolian leaders and given as tributes to the Qing emperors, other artifacts were made by craftsmen from the imperial household.

Most of the Thangka paintings were created nearly 300 years ago, around 1750, when the pavilion was first renovated. Heavy curtains prevent the sun from fading their colors. Under torchlight, the bright mineral pigments in the paint are still vibrant. “Those Thangka paintings have always hung there,” marveled Luo, “but they remain as fresh as ever.” Of the 1,970 paintings in the Palace Museum most were created by Tibetan painters during the reign of Emperor Qianlong.

Some large-scale wooden structures and porcelain pagodas have been equipped with an earthquake-proofing base, but most relics remain untouched. The pavilion is so crowded with artifacts that there is no room for visitors, which is why the pavilion has not been opened to the public. It has, however, been included in the “Digital Palace Museum” tour project and will be vividly displayed to the public using the virtual reality technology.

Luo also advises visitors interested in Tibetan Buddhist artifacts to visit the recently renovated Xianruo Hall in the gardens of Cining Palace (Palace of Benevolent Peace). The hall was where the empress dowager and imperial concubines went to worship the Buddha after the emperor had died.

Status of Tibetan Buddhism

The rich collection of Tibetan Buddhist artifacts in the Palace Museum is due to their accumulation at the height of Tibetan Buddhism in China.

In 1653 Emperor Shunzhi of the Qing Dynasty welcomed the fifth generation of the Dalai, then leader of the Gelug sect of Tibetan Buddhism, and dubbed him the title “Dalai Lama.” In 1713 Emperor Kangxi gave the fifth generation of Panchen the title“Panchen Erdeni,” thereby formally acknowledging the political and religious status of the Dalai and Panchen in Tibet. The influence of Tibetan Buddhism spread, and the number of Tibetan Buddhist halls in the Forbidden City expanded.

In 1780 the Sixth Panchen Erdeni arrived at the Forbidden City to congratulate Emperor Qianlong on his 70th birthday, coinciding with the peak of Tibetan Buddhist activity in the royal court. Thereafter, the influence of Tibetan Buddhism in the imperial court waned as the Qing Dynasty began to decline.

“After waking up, the emperors would light incense in one hall after another, before having breakfast in Qianqing Palace,” explained Luo. “The complex of Buddhist halls was very important to the court.”

Through Zhaofu Gate to the north of Yuhua Pavilion is a square where large-scale Buddhist ceremonies were held. The prayer flags used during these ceremonies still remain. At the end of each year, the emperor would take part in an exorcism ceremony, the most important Buddhist event in the imperial court. On that day, the emperor would sit beside the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama, as well as other senior monks, demonstrating the prominent status of Tibetan Buddhism in the Qing Dynasty.

Preservation of Artifacts and Cultural Exchange

After graduating from Peking University in 1989 with a degree in archeology, Luo Wenhua went to work at the Palace Museum. Today, as an internationally renowned scholar of Tibetan Buddhism, he is competent in English, Tibetan, Sanskrit, and German.

“Many artifacts are scattered throughout monasteries in Tibetan-inhabited regions,” said Luo, voicing his concerns about the preservation of Tibetan Buddhist artifacts. “Owing to a lack of funds and professionals, there has never been a systematic survey and many artifacts have not been catalogued. Preservation work is just beginning.”

To better protect Buddhist artifacts in Tibet, the Palace Museum signed an agreement with the government of Tibet Autonomous Region. The two parties will cooperate to build museums, study and restore artifacts, hold exhibitions and publish research. Archaeological research will gradually be carried out in Tibet Autonomous Region, and experts from the Palace Museum have already begun contributing to the preservation of artifacts at Jokhang Monastery.

“Along the Silk Road: Gupta Sculptures and Their Chinese Counterparts, 400-700 AD,” an exhibition held at the Palace Museum, finished its successful run early this year. Luo Wenhua acted as the independent curator of the exhibition. He had visited India, the birthplace of Buddhism, many times and each time brought back Buddhist texts.“India has a wealth of artifacts and cultural sites,”said Luo. “Historically, China and India conducted frequent exchanges, but in modern times, people of the two countries know little about each other.”Luo added that China and India should strengthen cultural communication.

When commenting on the international influence of Tibetology, Luo observed that Western countries are very interested in Tibetan Buddhist artifacts. People in the West have been studying Tibetology for over a century. The U.S., the U.K., France, and Germany have all made significant progress in Tibetan Buddhist studies, especially on Buddhism in Himalayan areas. China should cooperate with these countries.

Shan Jixiang, director of the Palace Museum, hopes the organization can take advantage of the palaces rich resources and artifacts and make it Chinas center for Tibetology, promoting cooperation between domestic and international experts.