生物经济中的生物准则城市

2017-04-28乔基姆布朗JoachimvonBraun

乔基姆·冯·布朗/Joachim von Braun

生物经济中的生物准则城市

Bioprincipled Cities in the Bioeconomy

乔基姆·冯·布朗/Joachim von Braun

城市化并不是一种现代的现象——早在工业革命时代,由于经济和政治权力集中于城市,城市化对于人群和商业的吸引力就已与日俱增。最近几十年来,城市化这一趋势并未改变——而且发展速度和规模达到了史无前例的水平[1]。在今后的30年内,城市发展和建设所需的资源可能会超过整个人类历史上的任何一个时代。为了让特大城市能够以可持续的方式运作,并为城市的居民以及众多(濒临灭绝的)生物体提供食物及保证其生活质量,创新解决方案是必不可少的手段[2]。而且当今的城市还需要向生物敏感型城市转型。这就需要将生物经济放在可持续城市发展战略的中心位置。通过将生物准则整合到城市规划和城市生活之中,发展生物经济,有助于打造更加绿色环保的城市,提高生活质量水平。

1 什么是生物经济?

生物经济理论是由尼古拉斯·乔治斯库-罗根1971年创立的[3],而胡安·恩里克斯-卡博特和罗德里格·马丁内兹于1997年在描述那些主要由现代生命科学突破所推动的经济部分时首次对生物经济这一术语给出了定义[4]。在欧洲,一群来自学术界和产业界的专家于2005年在政治层面引入了知识型生物经济这一概念,并且向欧盟介绍了生物经济的相关知识和观点看法。2007年5月30日,时任欧盟理事会主席国的德国主持召开了“迈向基于知识的生物经济”大会,并发布了 《科隆文件》1)。

当时主要是针对日益稀缺的油气资源而倡导发展生物经济。鉴于在过去5年中出现了新的钻探方法(液压破碎法)并且生物能源供应量进一步增加,油气储量有望坚持更长的时间,而且其价格也出现了大幅下跌。化石资源价格的预期上涨已经不再是推动当今生物经济的决定性因素了。然而,生物经济依然以保护资源和气候作为战略导向。经济体需要转向可再生资源和采取可循环的方式,以免给全球生态系统造成不可逆转的损害以及不可估量的经济风险[5]。

作为一种全新的而非基于政治和科学的概念,“生物经济”尚未形成一个被广泛认可的定义,这种情况并不奇怪。全球各地对于生物经济的理解有所不同——无论是在范围还是在方向上。我们可以广泛地将其定义为通过对生物资源、过程和原则的可持续生产和使用,为所有经济部门提供产品和服务[6]。这种生物经济定义并不专指替代其他资源的生物资源,而且也重点涉及了以生物知识和原则为基础开发新的以及可持续性更佳的替代产品和过程。如果脱离自然资源和生态资源的保护与再生这一基础原则,生物经济则无从谈起。

1.1 生物经济的经济相关性

一方面,生物经济具有非常悠久的历史和传统(烤制面包、酿造啤酒、贮藏食物、生产焦炭),另一方面,其又是一个新兴并具有创新性的事物(新型生物材料,生物药物,采用生物技术生产的食品配料、饲料和化妆品)。创新的生物经济建立在科学和技术过程的基础上。生物经济所涉及的领域包括医疗保健、化学、建筑、信息通信技术(ICT)和工程等。其足以和数字化相提并论,即ICT已渗透了整个经济。

生物经济(尤其是食品和医疗保健)几乎在全球所有的经济体中都扮演了重要角色。尽管可以通过生物资源来确定和量度经济部门的规模,但却难以衡量各个领域的生物过程和技术的增值情况。举例来说,欧洲的生物型经济在2013年实现的年度总营收为2.1万亿欧元左右,雇佣的人员超过了1700万人——约占欧洲劳动人口的9%。欧洲的生物型行业的非食品类生产活动的年营收额达到了4800亿欧元,其中的10%是由创新型生物经济(生物基化学品、药物和塑料)贡献的[7]。美国在这方面的数据与欧洲大体相当。在2013年,非食品类生物型产业的营收达到了3700亿美元左右,并且提供了大约400万个就业岗位[8]。

许多工业化国家和新兴国家都将生命科学和生物技术视为前景光明的创新领域和未来的增长源[9]。例如,印度和中国的生物技术型经济在过去的10年已经取得了长足的发展[10,11],并且建立了一套竞争力十足的科学和产业基础设施。而且巴西也在生物燃料和酒精能源汽车领域走在了世界前列[12,13]。

1.2 可持续生物经济的前景

2015年,联合国的193个成员国就可持续发展目标达成了共识(《2030议程》),此举掀起了发展生物经济的势头以应对严峻的社会挑战。实际上,17个可持续发展目标(SGDs)中的大多数都离不开可持续生物经济:消除饥饿(SDG 2)、良好健康与福祉(SDG 3)、清洁饮水和卫生设施(SDG 6)、廉价和清洁能源(SDG 7)、体面工作和经济增长(SDG 8)、可持续城市和社区(SDG 11)、负责任的消费和生产(SDG 12)、气候行动(SDG 13)、水下生物(SDG 14)和陆地生物(SDG 15)2)。

2 生物准则城市面临的挑战和前景

德国生物经济理事会在2015年主导开展了生物经济的一项“旗舰项目”——国际德尔菲研究i。此次活动的目的是就进一步的创新支持和新政策找出那些最为重要的生物经济相关领域,并向德国政府提供建议。生物准则城市是德国生物经济理事会提出的四大旗舰项目(生物准则城市、人造光合作用、新食品系统、全球治理)之一。这些旗舰项目经过了两轮评估、讨论和改进,并且在经典的德尔菲调查框架下加入了新的项目。来自世界各地以及各类学科的2000多名与生物经济相关的专家受邀对旗舰项目的相关性和可取性进行评估。共计有292名参与者完成了第一轮调查工作,149名参与者参加了第二轮调查。在第一轮调查中,生物经济德尔菲调查为各个旗舰项目给出了更加全面的愿景,以便进行评估并征求意见(框1)。调查还要求参与者另行提出并说明其他对于今后全球经济发展有重要意义的旗舰项目。3个新的旗舰项目(可持续的海洋产业、生物炼制4.0和发展消费市场)正是源自于参与者的反馈意见和建议。在第二轮时,以匿名的形式提供了第一轮调查汇总之后的答复并且提供了(重新)评估7项旗舰项目的机会[2]。

“生物准则城市”被列为相关度最高的旗舰项目之一。约有40%的参与者将相关性评为极高,约有1/3的参与者认为其具有相关性。大多数参与者估计这一愿景有望在2040年之前实现。在第二轮的时候,调查要求参与者评价此旗舰项目各个相关方面的相关性。在汇总之后,他们给出的答案可归入三大领域:城市规划、建造及建筑和城市生产(图1)[2]。

在城市规划领域,参与者认为发展可持续城市代谢这一方面的相关度最高。其涉及了城市封闭的材料和营养循环,即通过雨水收集、饮水梯度利用、废水净化和营养恢复来实现这一理念。在这一领域已经实现了生物经济创新。举例来说,德国最大的城市供水公司柏林自来水公司已开发了一套获得专利的从废水污泥中回收磷的解决方案。磷属于全球稀缺资源并且正在不断消耗殆尽。但这一元素却是植物营养和食品生产不可或缺的成分。利用发酵器以生物方式对废水进行第一道处理。借助化学物理过程,该公司能够从污泥中回收磷酸氨镁(MAP)—— 一种优质的长效矿物肥料。这种名为“柏林植物”的MAP长效肥料产品的销售对象是城市园艺工作者和城市园艺农场(图2)。该产品中含有重要的矿物质和微量元素,并且不含任何有害物质。这一磷回收技术可以更轻松、更好地处理污泥,同时也节约了大量的金钱[14]。另一个城市中的封闭材料循环例子是使用咖啡渣来生产生物复合材料(采用咖啡渣和其他生物资源制成的塑料)。这些材料可用于家具、灯或餐具。咖啡渣还可以作为建筑材料使用,例如用于道路[15]。

绿化城市空间的创新方法被认为是另一个与未来城市规划相关的方面。绿化有助于净化空气和平衡城市内的极端温度。其有利于社会福祉及提高城市的复原能力,例如吸收雨水。这一方面包括将住宅安排在城市中心,让工作、购物和休闲场所融为一体[2]。绿化城市空间已经成为了全球各个城市的重要手段。举例来说,在纽约(如布鲁克林大桥公园)、柏林(如公主花园)或米兰,城市园林绿化这一概念已被彻底改造。米兰博埃里建筑设计事务所的设计师们设计了一整套名为“垂直森林”的充满森林气息的高层建筑群。这些混凝土建筑物的4个外立面几乎都种满了树木,树木的数量在900株左右,这些树木种植在伸出楼外的阳台上(图3)。绿化区域涉及的森林面积约为20,000m2。这些植物并不只是装饰点缀物,而是体现了建筑理念的一部分,包括一套灌溉系统和负责植物修剪的“空中园丁”[16]。博埃里建筑工作室将在一个新项目上将绿色设计提升至更高层次。在名为山地森林酒店的项目中,他们设想建造一座从地基到屋顶全部实现绿化并拥有250个房间的酒店。山地森林将会建在中国的贵州,并且将被设计成垂直的“森林山地”风格(图4)[17]。

在德国,一家名为绿色城市解决方案的创业公司发明了一套旨在对付城市中的最大健康风险之一——空气污染的移动式自行维护绿化系统。发明者将这种结构叫做“城市树木”,其原因是这些高科技元素(图5)的作用如同自然界的树木一般,4m高的城市树木上覆有一种特别的苔藓类植物,能够吸收恶劣的空气。实际上,它每年能够吸收30kg的CO2。该公司进一步指出这种人工树木的作用相当于275棵自然树木,并且尤其适合于市区环境。为了避免它们脱水,利用“物联网技术”为苔藓提供水分[18]。举例来说,香港的湾仔将会放置一棵城市树木,因为这里是游客量最大的区域之一[19]。

在建筑领域,参与德尔菲研究的人员将生物启发式设计解决方案评为未来生物准则城市相关度最高的方面。在设想中,此类设计解决方案利用能源库、自然照明、废水处理系统和战略性种植来实现能源和水的自主性[2,20]。这一领域已经开展了一些项目,例如,德国汉堡拥有全球第一座采用了透明的生物反应器制成的水藻外立面的建筑(图6)。这种外立面不仅能够产生热量和生物量,而且还可以通过绿藻生长时的化合作用吸收CO2。根据模型计算得出的数据,这种外立面可以将48%的入射阳光转化成可用的生物能源。另外,小球藻可以起到光线防护的作用,它们可以根据阳光的强度来调节自身的颜色。每个反应器以两块玻璃板进行固定,从而进一步保证了隔热和隔音效果[21]。

生物基材料和剩余材料的使用被列为未来建造和建筑项目的另一个相关方面。它们有助于最大限度地减少能源密集型建筑材料和不可再生建筑材料的使用,并且还可以在保证成本效益的情况下用于翻新现有的建筑物[2,20]。鉴于其优秀的材料性能以及更好的环境平衡性,自然资源可以作为建筑材料,通用结构材料或施工及室内施工材料使用。自人类开始修建房屋以来,他们已将诸如木材和稻草之类的生物资源作为建筑材料来使用。近年来,可持续性和节能已成为了建筑行业日益重要的话题。目前已从可再生资源中开发出了创新高科技建筑材料。这就是生物基建筑材料再次得到广泛认可的原因[22]。荷兰出现了利用生物基塑料材料以3D打印方式建成的立面和建筑构件。这些构件可以回收利用或者重新塑造(图7,见本刊64-67页)。举例来说,奥地利维也纳的一些高层建筑已经采用了创新的木制结构,当地正在修建全球最高的木制建筑物“HoHo大厦”(图8)。

近年来,天然隔热材料的需求量也有所上升。其生产耗能更少,并且还可以为家庭的气候及人体健康带来积极的影响。木纤维隔热材料正是其中的一个例子,那些来自于去纤维废纸、麻类植物、牧草、稻草和羊毛的纤维素也可以作为隔热原料。

另一个即将兴起的建筑业话题是天然涂料的应用,生产这些涂料的原料包括天然矿物质和可再生植物资源,与传统的化学产品相比(例如丙烯酸产品和醇酸树脂产品),这些涂料中的溶剂含量更低。在100多种天然涂料产品中,最为重要的包括墙面涂料、木器漆、天然树脂涂料、油和蜡[22]。

Urbanization is not a modern phenomenon– during the industrial revolution cities already became more and more attractive to people and business due to their concentration of economic and political powers. The trend of urbanization has not changed in recent decades–in contrary, it continues apace in unprecedented speed and scale[1]. In the coming 30 years, urban development and construction may require more resources than in the entire human history. Innovative solutions are needed in order to enable these mega cities to function in a sustainable way, to provide food and quality of life for their inhabitants and for a multitude of (endangered) living organisms[2]. And the cities of today also need to change toward biosensitivity. Tis puts the bioeconomy at the centre of sustainable urban development strategies. While integrating biological principles in urban planning and city life, the development of the bioeconomy can contribute to greener cities with higher levels of quality of life.

1 What is the Bioeconomy?

Bioeconomic theory was established by Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen in 1971[3]and the term bioeconomy was probably first defined by Juan Enriquez-Cabot and Rodrigo Martinez in 1997[4]who intended to describe the part of the economy which is primarily driven by the breakthroughs in modern life sciences. In Europe, the concept of a knowledgebased bioeconomy was politically introduced in 2005 by a group of experts from academia and industry who outlined the understanding and perspectives of such a Bioeconomy for the European Union. Te resulting so-called 'Cologne Paper' was published on 30 May 2007 in Cologne at the conference 'En Route to the Knowledge-Based Bio-Economy' hosted by the German Presidency of the Council of the European Union1).

At that time, bioeconomy development was particularly promoted in the face of ever-scarcer oil and gas resources. In view of new explorations (fracking) and an increase in the supply of renewable energy in the past 5 years, the oil and gas reserves are expected to last longer and prices have gone down dramatically. The bioeconomy of today is no longer predominantly driven by rising price expectations for fossil resources. However, resource and climate protection remain the strategic orientation for the Bioeconomy. Economies need to switch to renewable resources and adopt circular approaches in order to avoid irreversible damages of global ecosystems and incalculable economic risks[5].

Being a new, rather political and science-based concept, it should not be surprising that no generally accepted definition of 'bioeconomy' emerged right away. The understanding of bioeconomy differs worldwide – both in scope and in direction. It can be broadly defined as the knowledge-based production and use of biological resources, processes and principles to sustainably provide goods and services across all economic sectors[6]. This definition of bioeconomy does not refer exclusively to biological resources acting as substitutes for other resources, but focuses on the development of new and more sustainable products and processes on the basis of biological knowledge and principles. Bioeconomy can only work if it succeeds in protecting and regenerating natural resources and ecosystems.

1.1 Economic relevance of the bioeconomy

Bioeconomy is on the one hand very ancient and traditional (bread baking, beer brewing, food conservation, char coal production), and on the other hand new and innovative (novel biomaterials, biopharmaceuticals, biotechnologically produced ingredients for food, feed and cosmetics). The innovative bioeconomy is based on scientific and technological progress. It cuts across sectors, such as health care, chemistry, building, ICT and engineering. It can be compared to digitalization, i.e., ICT's penetration of the whole economy.

The Bioeconomy, especially food and health care, plays an important role in nearly all economies around the globe. Whereas it is possible to identify and gauge the size of economic sectors using biological resources, it is difficult to measure the value-added of biological processes and technology across sectors. The European biobased economy, for example, produced a total annual turnover of about 2100 billion EUR in 2013 and employed more than 17 million people – approximately 9% of the European workforce. Te non-food production of the European biobased industry generated an annual turnover of about 480 billion EUR, 10% of which are attributable to the more innovative bioeconomy (biobased chemicals, pharmaceuticals and plastics)[7]. In the US, the numbers are comparable. Te non-food biobased industry generated a turnover of about 370 billion USD and represented about four million jobs in 2013[8].

In many industrialized and emerging countries, the life-sciences and biotechnology are seen as a promising field of innovation and source of future growth[9]. India's and China's biotechnology –based economies, for example, have registered significant growth over the past ten years and established a competitive scientific and industrial infrastructure[10,11], Brazil, for example, has been at the forefront in the area of biofuels and ethanoldriven cars[12,13].

1.2 Te vision of a sustainable bioeconomy

The adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (Agenda 2030) by 193 countries in 2015 builds a momentum for the bioeconomy and its contributions to meeting the great societal challenges. In fact, a sustainable bioeconomy will be necessary to achieve a majority of the 17 sustainable development goals (SGDs): zero hunger (SDG 2), good health and well-being (SDG 3), clean water and sanitation (SDG 6), affordable and clean energy (SDG 7), decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), climate action (SDG 13), life below water (SDG 14) and life on land (SDG 15)2).

2 Challenges and visions of Bioprincipled cities

In 2015, the German Bioeconomy Council commissioned an international Delphi study on 'flagship projects' of the bioeconomy. The aim of this exercise was to recommend to the German Government where the most important bioeconomy-related fields for further innovation support and new policy may be found. BioprincipledCity was one of four flagship projects (Bioprincipled City, Artificial Photosynthesis, New Food systems, Global Governance) proposed by the German Bioeconomy Council. These flagship projects were assessed, discussed, improved, and new projects were added within the framework of a classic Delphi survey in two rounds. More than 2000 bioeconomyrelated experts from all over the world and from a broad range of disciplines were invited to evaluate both the relevance and desirability of the flagship projects. In total 292 participants completed the first survey round, and 149 participants the second round. In the first round, the Bioeconomy Delphi survey provided a more comprehensive vision of each flagship project for assessment and comments (BOX 1). The participants were also asked to add and describe additional flagship projects that are seen as very important for the development of the future global economy. Tree new flagship projects (Sustainable Marine Production, Biorefineries 4.0 and Developing Consumer Markets) were derived from participants' feedback and recommendations. In the second round, the aggregated but anonymous answers from the first round were provided alongside the opportunity to (re)assess the seven flagship projects[2].

'Bioprincipled City' was rated as one of the most relevant flagship projects. About 40% of participants rated the relevance as very high and around one third of participants considered it as relevant. Te majority of participants estimated that the vision could be realized by 2040.

In the second round, the participants were asked to rate the relevance of single aspects related to this flagship project. Teir answers were clustered into three areas: urban planning, architecture/ buildings and urban production (Fig. 1)[2].

In the field of urban planning, the participants considered the aspect of developing a sustainable city metabolism as most relevant. It relates to closing material and nutrient loops in cities, e. g. by rainwater collection, cascading use of drinking water, wastewater purification and nutrient recovery. Bioeconomy innovations in this area already exist. For example, the Berliner Wasserbetriebe, Germany's largest municipal water supply company, has developed a patented solution for recovering phosphorus from sewage sludge. Phosphorus resources are scarce globally and depleting quickly. However, they are vital for plant nutrition and thus food production. The waste water is first treated biologically in a fermenter. With the help of a chemical-physical process the company is able to recover magnesium-ammonium-phosphate (MAP)– a high-quality mineral long-term fertilizer – from the sludge. Under the name of 'Berliner Pflanze' (Berlin plant) the MAP is marketed to city gardeners and urban horticultural farms as a long-term fertilizer (Fig. 2). It contains important minerals and trace minerals and is free from any harmful substances. Thanks to the phosphor recovery the sludge is easier and better to treat which saves a lot of money[14]. Another example of closing material loops in cities is the use of waste coffee grounds for producing bio-composite materials (plastics made out of coffee grounds and other biological resources bound by bio-resins). These are used in furniture, lamps or for dishes. Coffee grounds might also serve for building materials, e.g. for roads[15].

Innovative ways of greening urban spaces were rated as another relevant aspect of urban planning in the future. Greening helps cleaning the air and balancing temperature extremes in cities. It contributes to resilience, e.g. absorption of rain water, and to social well-being. This aspect includes the vision that housing is organized in urban centres where work, shopping and leisure space become much more integrated[2]. Greening urban spaces has become an important instrument for a variety of cities around the globe. Examples can be found in New York (e. g. Brooklyn Bridge Park), Berlin (e. g. Prinzessinnengärten) or Milan, where the concept of urban gardening has been reinvented. Te architects of the Milan architecture Studio Boeri designed an ensemble of forested high-rise buildings, called 'Bosco Verticale' (vertical forest). Both concrete buildings were planted on almost all four facades with about 900 trees, which were placed on projecting balconies (Fig. 3). The greening area relates to a forest area of about 20,000 m2. The plants are thereby not to be meant as decorative attachment, they rather represent a part of an architectural concept, including an irrigation system and 'flying gardeners' who are responsible for trimming the plants[16]. With a new project the architects of Studio Boeri will take the green design to a next level. Under the so-called Mountain Forest Hotel project, they envisaged to build a 250-room hotel which will be greened from the foundation to the roof. Te Mountain Hotel will be built in Guizhou/China and will be designed as a vertical 'forest mountain' (Fig. 4)[17].

In Germany, the start-up company Green City Solutions invented a mobile and self-maintaining greening system with the aim to cope with one of the greatest health risks in cities – air pollution. The inventors call their quadratic structures 'City Trees' as the high-tech elements (Fig. 5) are working like natural trees. The four-meter-tall City Trees are cladded with a special species of moss, which absorbs poor air. In fact, it binds 30 kilos of carbon dioxide per year. The company further states that one of the artificial trees performs as 275 real trees and that they are therefore in particular suitable for urban areas. In order to prevent them from drying out, a 'internet-of the things-technology' provides the mosses with water[18]. In Hong Kong, for example, a City Tree will be placed in Wan Chai, one of Hong Kong's most heavily-travelled areas[19].

In the field of architecture and buildings the participants of the Delphi study rated bio-inspireddesign solutions as most relevant aspect of a future Bioprincipled city. According to the vision, such design solutions make use of energy depots, natural lighting, waste water systems and strategic planting to achieve energy and water autonomy[2,20]. Existing projects in this field can be seen, for example, in Hamburg/Germany, where the world's first building was equipped with an algae facade made of glassy bioreactors (Fig. 6). This facade does not only produce heat and biomass; it also binds carbon dioxide through the photosynthesis of growing green algae. According to model calculations, the facade could convert about 48% of the incoming sunlight into usable bioenergy. Moreover, the chlorella algae serve as light protection as they adjust its colour to the sun's intensity. Every reactor is fixed with two glass plates, which further ensure thermal insulation and noise protection[21].

Usage of biobased and residual materials were rated as another relevant aspect of future architecture and building projects. They should help to minimize the use of energy-intensive and non-renewable building materials and should also be used for costefficient retrofits of existing buildings[2,20]. In the light of their good material properties and their improved environmental balance, natural resources can serve as materials for buildings, general construction materials, or for construction and interior construction. Since humans have built houses, they have used biological resources such as wood and straw as building materials. In recent years, sustainability and energy efficiency have become increasingly important topics in the construction sector. Innovative and high-tech building materials have been developed from renewable resources. This is why the acceptance of biobased building materials is rising again[22].In the Netherlands, facades and building elements are 3D-printed with biobased plastic materials. These elements can be recycled or re-modelled if needed (Fig. 7, page 64-67). Innovative wood construction, for example, is used for high-rise buildings in Vienna/Austria, where the world's highest wooden building, the HoHo Building, is currently under construction (Fig. 8).

Since recent years, also natural insulation materials have enjoyed greater demand. Their production requires less energy and they have positive effects on household climate and human health. Examples are wood fibre insulation materials, but also cellulose from defibrated old paper, hemp, ax, meadow grass, straw and sheep's wool serve as raw material for insulation.

Another upcoming topic in the construction sector is the application of natural paints, which are produced from natural mineral and regenerative plant sources, and contain far less solvent – in contrast to conventional chemical products, such as acrylic and alkyd products. Among the more than 100 natural natural-paint products, wall paints, wood lacquers, natural resin paints, oils and waxes are among the most important[22].

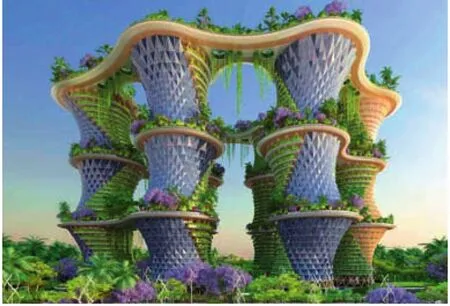

In the area of urban production, the participants of the Delphi study rated the aspects of 'green' industrial production and urban farming as most relevant. Visions for green industrial production are developed, for example, by the Belgian architect Vincent Callebaut, whose 'Hyperions' project aims to combine archaeology and sustainable food systems, that grow up around six timber towers in New Delhi/India (Fig. 9, page 68-77). The project is further designed to integrate urban renaturation, small-scale farming, environmental protection and biodiversity. The vertical village provides spaces for business incubators, living labs, co-working spaces and multi-purpose rooms. All apartments are equipped with cascading hydroponic balconies and indoor furniture is made from natural materials like tamarind and sandalwood. Organic aquaponics and hydroponic greenhouses further provide all residents with fresh vegetables. Food is also produced in neighbouring agroforestry fields, which ensure food autonomy to the residents[23].

But urban production is not only a future vision, it has started to become a reality in a variety of cities worldwide, e. g. in New York's Floating Food Forest called Swale, which sails around the city and offers fresh foods like vegetables but also offers plants, a seed exchange program, and a crowd-sourced cookbook[24]. In Berlin, for example, sustainable urban production takes place up on the roofs. Within the project 'roof water farm', scientists from the Technical University Berlin focus on combining fish farming and plant cultivation (Fig. 10). In the same time, they aim to demonstrate paths towards innovative city water management, while exploring and communicating potentials and risks of redesigning across sectors of infrastructure[25].

The Delphi study revealed, that the Bioprincipled City is widely regarded as feasible but with limitations. Some participants, for example, doubted its validity in megacities, others instead saw it embedded in a regional context. Vertical farms and urban farming in general were regarded with scepticism and if participants argued in favour of urban farming, they stressed the limitations of crops and scale. Finally, it turned out that the surroundings, regions, existing infrastructure, situation and size need to be considered in order to realize the flagship project[2].

3 The way forward–steps toward Bioprincipled cities

A first field of action should focus on how bioeconomy can contribute to improve the urban quality of life. Relevant research topics include, i.e. greening technologies and greening systems, which should help to increase urban resilience and living climate. Sustainable solutions, e. g. for green roofs or mobile greening elements, require further basic and applied research. Furthermore, new concepts for urban gardening and the integration of existing allotment gardens were identified as important research topics.

In the area of architecture and construction we need energy-positive or recyclable buildings, to ensure a reduced resource footprint. The development of biobased materials should be further promoted, while their contribution to sustainable building need to be monitored and evaluated. To combine all this with esthetics and beauty is the challenge for the architecture community.

Moreover, large parts of urban transportation need to be shifted to electric drives and alternative fuels, such as new generation biofuels. Technological innovations in this area are an urged need, just like new concepts for urban food production. Concepts on sky and peri-urban farming, for example, require intensive research and technological breakthroughs in different disciplines (e. g. crop research, biological plant protection, farming and lighting techniques, nutrient cycling etc.). Research is necessary to demonstrate how changes in regulations can possibly contribute to implementation success.

Another relevant research issue for the resource-efficient city of the future are circular systems for biobased materials and energy[26]. All these efforts in applying biobased principles and materials in urban planning and design will contribute to making urban areas more environmentally-friendly and more liveable for its residents.

BOX 1: Flagship Project Bioprincipled City

The integration of biological principles into urban planning and city life has become a key element for the achievement of greener cities with high levels of self-sufficiency and quality of life. Locally coordinated production, provision, use and recycling systems ensure that mega cities function on the basis of closed material and energy cycles. Emissions, waste and losses are minimized. Renewable resources, cropping techniques and biotechnology play a major role in closing the loops. Valuechains are based on the cascading use of natural and renewable resources, e.g. water. Urban (vertical) farms are economically and ecologically efficient high-tech production centres. Spaces for recreation, production, services, work and living are integrated and decentralized in city districts. Mega cities innovate sustainable building designs and construction techniques by referring to biological principles and renewable resources. Green areas, and especially the green belts of big cities, are recognized as important retreats and contribute to biodiversity, water regulation and filtration, air cleaning, halting soil erosion and desertification, mitigating temperature extremes (saving energy consumption) and human recreation.

框1:旗舰项目生物准则城市

在城市规划和城市生活中整合生物准则已经成为了打造更加绿色环保的城市,以及进一步提高自给自足水平和改善生活品质的关键要素。本地的协调化生产、供应、使用和循环系统确保那些超大城市能够在封闭的物料和能源循环支持下正常运作。最大限度地减少排放物、废物和损耗。可再生资源、杂交技术和生物技术在解决这些循环方面发挥了重要作用。价值链建立在自然和可再生资源(例如水)梯度利用的基础上。从经济层面和生态层面而言,作为高科技生产中心的城市农场无疑是一种十分高效的手段。休闲、生产、服务、工作和生活空间分散在市区各地。超级城市通过借助生物准则和可再生资源,在可持续建筑设计和建筑技术方面不断创新。绿化区,尤其是大型城市的绿化带,作为重要的栖息休养地,有助于保护生物多样性、调节和过滤水资源、净化空气、阻止水土流失和土地荒漠化缓解极端温度(节约能耗),以及为市民提供休憩场所。

相关性 ,所有参与者/Relevance. All participants

时间范围,所有参与者/Time horizon. All participants

特定方面的相关性

城市规划/Urban Planing

·城市封闭的材料循环可以有效地废物利用(零废弃),如通过雨水收集、废水净化、建立水资源的梯度利用、空气净化、取代不可回收材料或使用可再生材料等。(n=161) ·城市具有吸引力且完全融入到更大区域内。郊区将成为城市可持续食品、原料和能源供应体系的一部分,而非纯粹的郊外住宅区。(n=163)

·为确保居民的社会幸福度,住宅被安置在有绿化空间的城市中心区。大多数居民可以使用自行车(占主导地位的个人交通方式),公共交通工具或步行作为日常生活的一部分,因为工作、购物及休闲空间均已融入在居住区当中。(n=164) ·大城市通过应用环境生物技术、优化植物和生物种植技术,建立并恢复了湿地、森林和绿地。(n=163)

·Cities close material loops, e.g. by collecting rainwater, cleaning wastewater and establishing cascading use, purifying the air or substituting non-recyclable and renewable materials so that 'waste' is effectively abolished ('zero waste'). (n=161)

·Te cities are attractive and fully integrated into the region. Suburban areas will become part of sustainable urban supply systems for food, feedstocks and energy instead of being designed as purely dormitory towns. (n=163)

·Housing is organized in urban centre with green spaces ensuring social well-being. A majority of residents can use bicycles (dominant mode of private transport), public transport or walk as part of their daily routine, because work, shopping and leisure spaces are integrated into urban residential areas. (n=164)

·Big cities establish and recover territories for wetlands, forests and green spaces by applying enviromental biotechnology, optimized plants and biological cropping techniques. (n=163)

·基于仿生和自然法则的导航、交通规则及物流体系(如:来源于群居昆虫的演算)。(n=161)

·Navigation, traffic regulation and logistic systems function on the basis of bio-inspired and natural principles (e.g. algorithms derived from social insects). (n=161)

建造及建筑/Architecture and Buildings

·设计方案与功能性材料通过能源储藏、自然采光、废水系统和战略性的种植,实现了能源和水的自主性。(n=162) ·生物基材料和残余材料(如木材或生物基复合材料等)将能源密集型材料和不可再生建筑材料的使用降至最低。它们也被用于既有建筑物成本效益的改造。(n=162)

·

Design solutions and functional materials make use of energy depots, natural lighting, waste water systems and strategic planting to achieve energy and water autonomy. (n=162) ·Biobased and residual materials, such as wood or biobased composites, successfully minimize the use of energy-intensive and non-renewable building materials. Tey are also used for cost-efficient retrofits of existing buildings. (n=162)

城市生产/Urban Production

·绿色的工业生产(洁净的空气、无噪音、绿色物流等)与住区生活共存。(n=163)

·城市农场(如天台或立面)和城市森林,采用集散的方式向商店、住宅区及餐厅提供新鲜食材。 (n=163)

·Industrial production is 'green' (clean air, silent, green logistics, etc) and co-exists with residential living. (n=163)

·Urban farms (e.g. on roof tops or facades) and urban forestry enable a decentralized and healthy provision of fresh food in shops, residential buildings and restaurants. (n=163)

1 德尔菲研究部分结果/Te part of Delphi study(图片来源/Source: 参考文献/Reference [2])

2 “柏林植物”/ 'Berliner Pflanze'(图片来源/Source: GreenTec Awards, http://www.ecowoman.de/25-haus-garten/4001-duengerberliner-pflanzen-erhielt-den-begehrten-greentec-award)

3 意大利米兰的“空中森林”/Bosco Verticale, Milan, Italy(图片来源/Source: Stefano Boeri Architetti, http://www. stefanoboeriarchitetti.net/en/portfolios/bosco-verticale/#)

4 山地森林酒店/Mountain Forest Hotel(图片来源/Source: Stefano Boeri Architetti, http://inhabitat.com/vertical-forestmountain-hotel-will-clean-the-air-in-guizhou-china/)

5 城中树/City Tree(图片来源/Source: Green City Solutions, http://greencitysolutions.de)

6 德国汉堡藻墙大楼/Algae Building, Hamburg, Germany(图片来源/Source: KOS Wulff Immobilien GmbH, http://www. biq-wilhelmsburg.de)

7 荷兰欧盟大楼的3D打印立面和建筑构件/3D printed facades and building elements of the Dutch EU building(图片来源/ Source: DUS Architects, https://www.dezeen.com/2016/01/ 12/european-union-3d-printed-facade-dus-architects-holland/)

在城市生产领域中,参与德尔菲研究的人员将“绿色”工业生产和城市农业评为相关度最高的方面。在绿色工业生产的愿景上已经取得了一定的发展,举例来说,比利时建筑师文森特·卡勒博的“亥帕龙”项目计划将考古学与可持续食品系统相结合,项目由位于印度新德里的6个花园塔构成(图9,见本刊68-77页)。项目设计进一步整合了城市自然再造、小规模农业、环境保护和生物多样性。垂直村落为企业孵化器、生活实验室、联合办公场所和多用途房间提供了空间。所有的公寓住宅都配有阶式水耕露台,并且室内的家具均采用罗望子和檀香木等天然材料制造而成。有机养耕共生和水耕温室进而为所有的居民提供新鲜蔬菜。周边的农林场也可以出产食物,确保居民的食物自主性[23]。

但城市生产并非只是一种未来的景象,在全球许多城市已开始成为现实。它不仅能够提供蔬菜之类的食物,而且还能提供植物、种子交换项目和源于群众的食谱[24]。举例来说,在柏林,可持续城市生产在建筑屋顶发扬光大。在“屋顶农场”项目中,来自柏林工业大学的科学家专注于养鱼业与植物种植相结合(图10)。他们还打算在探索和交流基础设施行业重新设计的潜力和风险的同时对创新型城市水管理途径加以证明[25]。

德尔菲研究表明,参与人员普遍认为生物准则具备可行性但也有一些局限性。举例来说,一些参与者对其在特大城市中的有效性表示怀疑,其他一些人则认为其融入了地域环境。总的来说,他们对垂直农场和城市农业持怀疑态度,赞成城市农业的参与者强调了作物和规模的局限性。最后,其结果表明,为了实现旗舰项目,需要对周边环境、地区、现有的基础设施、情况和规模大小加以考虑[2]。

8 奥地利维也纳Hoho大厦的视觉效果图/Visualization of Hoho House, Wien, Austria(图片来源/Source: Entwicklung Baufeld Delta GmbH, http://www.hoho-wien.at)

9 文森特·卡勒博建筑设计事务所设计的“亥帕龙”视觉效果图/Hyperions vision by Vincent Callebaut(图片来源/Source: Vincent Callebaut Architecture, http://vincent.callebaut.org/ zoom/projects/160220_hyperions/hyperions_pl018.jpg)

10 德国柏林的“屋顶农场”/'Roof Water Farm' in Berlin, Germany(图片来源/Source: Susanne Feldt, http:// zerowastelabs.com/ZWL/field-trip-roof-water-farm/)

3 前进之路——迈向生物准则城市

该领域的首项行动应将重点放在生物经济如何才能有助于提高城市生活质量上。相关的研究课题包括有助于提高城市恢复能力和改善生活气候的绿化技术和绿化系统;可持续解决方案,例如绿色屋顶或移动式绿化构件,要求开展进一步的基本研究和应用研究。此外,城市园林化及整合现有社区园林的新理念也被确认为重要研究课题。

在建造及建筑领域,我们需要低耗能或可回收利用的建筑物,以确保缩减资源足迹;应当进一步倡导开发生物型材料,但需要对它们在可持续建筑方面的贡献力度进行监测和评估。将以上几点与美学和美观相结合则是建筑界面临的挑战之一。

另外,大部分城市交通需要转为电力驱动和替代燃料(例如新一代的生物燃料)。这一领域迫切需要技术创新,正如城市食品生产新理念一样。举例来说,空中农业和城市边缘地区农业理念需要在不同的学科开展深入研究和取得技术突破(例如,作物研究、植物病虫害生物防治、农业和光照技术、养分循环等)。为了证明修改法规有利于项目的实施成功,有必要开展研究工作。

另一个与未来的资源节约型城市相关的研究课题是生物型材料和能源的循环系统[26]。所有这些旨在于城市规划和建筑设计中应用生物准则和生物材料的努力,都将为建筑居民营造一个更加环保和宜居的城市环境做出贡献。

编注/Editor's Note

i 德尔菲法:Delphi Method,调查者拟定调查表,按照规定程序通过函件征询专家组成员意见,专家组成员之间通过调查者的反馈材料匿名地交流意见,经过若干轮反馈,专家们的意见逐渐集中,最后获得有统计意义的专家集体判断结果,具有匿名性、多次反馈性及统计性3个特点。

注释/Notes

1)该文件体现了2007年1-6月期间举行的6次研讨会的研究讨论结果。参与者对以下方面进行了讨论:(1)框架,(2)食物,(3)生物材料和生物工艺,(4)生物能源,(5)生物医药,(6)新理念和新兴技术。/It presents the findings of six workshops which were held between January and March 2007. The participants discussed the following aspects: (1) Framework, (2) Food, (3) Biomaterials and Bioprocesses, (4) Bioenergy, (5) iomedicine and (6) New Concepts and Emerging Technologies.

2)参见联合国秘书长可持续发展目标特别顾问及可持续发展解决方案网络负责人杰弗里·萨克斯发表的演讲/ See speech of Jeffrey Sachs, Special Advisor on Sustainable Development Goals to the UN-Secretary General and Director of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K0E5Gvf8lPs

参考文献/References

[1] Dobbs, R., Remes, J., Manyika, J., Roxburgh, C., Smit, S. & Schaer, F. Urban world: Cities and the rise of the consuming class. McKinsey Global Institute. (2012) [2016-11-25] http://www.mckinsey.com/globalthemes/urbanization/urban-world-cities-and-the-riseof-the-consuming-class.

[2] German Bioeconomy Council. Global Visions for the Bioeconomy: an International Delphi-Study. (2015a) [2016-11-25] http://biooekonomierat.de/fileadmin/ Publikationen/berichte/Delphi-Study.pdf.

[3] Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen: The Entropy Law and the Economic Process. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1971.

[4] Enriquez-Cabot, J. (1998). Genomics and the World's Economy. Science 281: 925-926. [2016-11-25] http://science.sciencemag.org/content/281/5379/925. [5] German Bioeconomy Council. Positionen und Strategien des Bioökonomierates. (2014) [2016-04-26] http://www.biooekonomierat.de/fileadmin/ Publikationen/empfehlungen/Strategiepapier.pdf.

[6] Global Bioeconomy Summit. Making Bioeconomy Work for Sustainable Development. (2015) [2016-11-29] http://gbs2015.com/fileadmin/gbs2015/ Downloads/Communique_final.pdf.

[7] Ronzon, T., Santini, F. & M'Barek, R. The Bioeconomy in the European Union in numbers. Facts and figures on biomass, turnover and employment. (2015) [2016-04-26] https://biobs.jrc.ec.europa. eu/sites/default/files/generated/files/documents/ BioeconomyFactsheet_Final.pdf.

[8] Golden, J. S., Handfield, R. B., Daystar, J. & McConnell, T.E. An Economic Impact Analysis of the U.S. Biobased Products Industry: A Report to the Congress of the United States of America. (2015) [2016-05-10] http://www.biopreferred.gov/ BPResources/files/EconomicReport_6_12_2015.pdf.

[9] OECD. G20 Innovation Report 2016. (2016) [2016-11-28] https://www.oecd.org/sti/inno/G20-innovation-report-2016.pdf.

[10] Biotechnology Innovation Organisation (BIO). Accelerating Growth – Forging India's Bioeconomy. Verfügbar unter, 2014. [2016-04-26] https://www. bio.org/articles/accelerating-growth-forging-indiasbioeconomy.

[11] Mengjie. China's bioindustry expands: official. (2015) [2016-11-25] http://news.xinhuanet.com/ english/2015-07/24/c_134444728.htm.

[12] Brazilian Sugarcane Industry Association (UNICA). Why advanced sugarcane ethanol is a sweet deal for Brazil. (2015) [2016-04-26] http://www.unica.com. br/guest-columnist/25629667920310875715/whyadvanced-sugarcane-ethanol-is-a-sweet-deal-forbrazil/.

[13] El-Chichakli, B., von Braun, J., Lang, C., Barben, D. & Philp, J. (2016). [2016-7-14] Policy: Five cornerstones of a global bioeconomy. Nature 535: 221–223. [2016-11-25] http://www.nature.com/news/policy-fivecornerstones-of-a-global-bioeconomy-1.20228.

[14] Berliner Wasserbetriebe. Berliner Pflanze -Der mineralische Langzeitdünger. (2016) [2016-11-25] http://www.bwb.de/content/language1/html/6946.php.c

[15] GIE Media. University adds coffee grounds to asphalt mix. (2016) [2016-11-28] http://www. recyclingtoday.com/article/university-adds-coffee-toasphalt-mix/.

[16] Pollmeier, S. Faszination Wolkenkratzer. (2016) [2016-11-24] http://www.arte.tv/guide/de/058346-003-A/faszination-wolkenkratzer.

[17] DiStasio, C. Vertical forest Mountain Hotel will clean the air in Guizhou, China. (2016) [2016-11-24] http://inhabitat.com/vertical-forest-mountain-hotelwill-clean-the-air-in-guizhou-china/.

[18] Herberg, R. Künstliche Bäume sammeln CO2 ein. (2016) [2016-11-24] http://www.wiwo.de/ technologie/green/living/city-tree-kuenstlichebaeume-sammeln-co2-ein/13988458.html.

[19] Trentmann, N. Diese genialen Quadrat-Bäume sollen Smog wegfiltern. (2016) [2016-11-24] https://www. welt.de/wirtschaft/article154677312/Diese-genialen-Quadrat-Baeume-sollen-Smog-wegfiltern.html.

[20] German Bioeconomy Council. Bioeconomy Policy (Part II): Synopsis of National Strategies around the World. (2015b) [2016-04-26] http:// www.biooekonomierat.de/fileadmin/Publikationen/ berichte/Bioeconomy-Policy_Part-II.pdf.

[21] Gabrielczyk, T. Diese lebende Hauswand produziert Energie. (2013) [2016-11-24] https:// www.welt.de/wissenschaft/article115860368/Dieselebende-Hauswand-produziert-Energie.html.

[22] German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. Bioeconomy in Germany. (2014) [2016-11-24] https://www.bmbf.de/pub/Biooekonomie_in_ Deutschland_Eng.pdf.

[23] Smith, H. Vincent Callebaut's hyperions is a sustainable ecosystem that resists climate change. (2016) [2016-11-24] http://www.designboom.com/ architecture/vincent-callebaut-hyperions-sustainableecosystem-02-22-2016/.

[24] Swale. Swale. (2016) [2016-11-25] http://www. swaleny.org/about.

[25] Technical University Berlin. Roof Water Farm. (2016) [2016-11-25] http://www.roofwaterfarm.com/ueber/.

[26] German Bioeconomy Council. Empfehlungen des Bioökonomierates: Weiterentwicklung der "Nationalen Forschungsstrategie Bioökonomie 2030". (2016) [2016-11-25] http://biooekonomierat.de/ fileadmin/Publikationen/empfehlungen/181116_ Ratsempfelungen_fu__r_die_Weiterentwicklung_der_ Forschungsstrategie_final.pdf.

[27] Efken, J., Dirksmeyer, W., Kreins, P. & Knecht, M. Measuring the importance of the bioeconomy in Germany: Concept and illustration. NJAS -Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences (77): 9–17. (2016) [2016-11-25] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/ article/pii/S1573521416300082.

[28] German Bioeconomy Council. Bioökonomie-Politik-Empfehlungen für die 18. (2013) [2016-04-26] Legislaturperiode.http://www.biooekonomierat. de/fileadmin/Publikationen/empfehlungen/ Politikempfehlungen.pdf.

[29] Intensa san Paolo. La Bioeconomia in Europa. 2oRapporto. (2015) [2016-04-26] https://www. researchitaly.it/uploads/14174/Bioeconomia_%20 L abioeconomiaineuropa_dicembre2015. pdf?v=f9b7468.

作者介绍:德国政府生物经济理事会主席,ZEF发展研究中心主任,波恩大学教授/Chair, German Government's Bioeconomy Council; Director, Centre for Development Research (ZEF); Professor, University of Bonn

2016-12-18