Does playing a sports active video game improve object control skills of children with autism spectrum disorder?

2017-04-10JquelineEdwrdsSrhJeffreyTmrMyNioleRinehrtLisBrnett

Jqueline Edwrds,Srh Jeffrey,Tmr My,Niole J.Rinehrt,Lis M.Brnett,*

aSchool of Health and Social Development,Faculty of Health,Deakin University,Geelong,VIC 3125,Australia

bDepartment of Paediatrics,Faculty of Medicine,Dentistry and Health Sciences,University of Melbourne,Parkville,VIC 3052,Australia

cSchool of Psychology,Faculty of Health,Deakin University,Geelong,VIC 3125,Australia

dMurdoch Childrens Research Institute,Parkville,VIC 3052,Australia

Does playing a sports active video game improve object control skills of children with autism spectrum disorder?

Jacqueline Edwardsa,Sarah Jeffreya,Tamara Mayb,c,d,Nicole J.Rinehartc,Lisa M.Barnetta,*

aSchool of Health and Social Development,Faculty of Health,Deakin University,Geelong,VIC 3125,Australia

bDepartment of Paediatrics,Faculty of Medicine,Dentistry and Health Sciences,University of Melbourne,Parkville,VIC 3052,Australia

cSchool of Psychology,Faculty of Health,Deakin University,Geelong,VIC 3125,Australia

dMurdoch Childrens Research Institute,Parkville,VIC 3052,Australia

Background:Active video games(AVGs)encourage whole body movements to interact or control the gaming system,allowing the opportunity for skill development.Children with autism spectrum disorder(ASD)show decreased fundamental movement skills in comparison with their typically developing(TD)peers and might benefi from this approach.This pilot study investigates whether playing sports AVGs can increase the actual and perceived object control(OC)skills of 11 children with ASD aged 6–10 years in comparison to 19 TD children of a similar age. Feasibility was a secondary aim.

Methods:Actual(Test of Gross Motor Development)and perceived OC skills(Pictorial Scale of Perceived Movement Skill Competence forYoung Children)were assessed before and after the intervention(6×45 min).

Results:Actual skill scores were not improved in either group.The ASD group improved in perceived skill.All children completed the required dose and parents reported the intervention was feasible.

Conclusion:The use of AVGs as a play-based intervention may not provide enough opportunity for children to perform the correct movement patterns to influenc skill.However,play of such games may influenc perceptions of skill ability in children with ASD,which could improve motivation to participate in physical activities.

©2017 Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Autism spectrum disorder;Child;Exergaming;Fundamental movement skills;Physical self-perception;Xbox

1.Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder that is characterized by significan impairments in social communication,the presence of restricted or repetitive behaviors,and in many cases significan motor impairments.1ASD affects around 1%of the population worldwide,impacting on relationships,quality of life,and well-being.1

Interventions that target physical activity(PA)in individuals with ASD are beginning to gain an increased focus.PA provides numerousphysicaland psychologicalbenefit to children2and can have a positive influenc on behaviors specifi to ASD,such as reducing stereotypical behaviors and positively influencin social functioning,communication,and academic performance.3Currentrecommendationsstate thatchildren should participate in 60 min or more of developmentally appropriate moderate-tovigorous PA on most days of the week.2However,only 1 in 5 typically developing(TD)Australian children reachesthe recommended levelsofactivity,4and children with disabilities,including ASD,are even less likely.5,6Children with ASD can also have a strong preference forsedentary and indooractivitiesand activities that involve visual-spatial skills,such as screen-based activities.7

Not achieving PA recommendations may reduce the opportunity for children with ASD to improve their fundamental movement skills(FMS).FMS includes object control(OC) (i.e.,controlling implements and objects using the hand,foot,or other parts of the body,such as catching or throwing a ball), locomotor(i.e.,running,jumping),and stability or balance skills.8These skills are necessary in the development of more complex movement skills required for participation in sports orPA later in life.8,9A positive relationship between early childhood FMS level and PA later in life has been demonstrated.10Additionally,low FMS is associated with lower cardiorespiratory fitnes and an increased rate of obesity.9Perceived physical competence is also an important positive correlate of PA behavior in children and adolescents.11Stodden and colleagues12described in their conceptual model a positive spiral of engagement where children’s PA participation influence movement skill development,which increases perceptions of competence and in turn encourages more PA,thereby increasing their movement competence.

Approximately 80%of children with ASD show decreased FMS mastery in comparison with theirTD peers.8,13Poor movement skills can impact the ability of children with ASD to participate in group activities14and to develop social relationships with their peers.15Impairments in FMS,particularly ball skills and balance,are also associated with emotional or behavioral disturbance in children with ASD.16

Yet few evidenced-based interventions specificaly target FMS for children with ASD.Group-based interventions can result in significan stress due to physical skill and social interaction requirements.17Along with technological advancements came the rise of active video games(AVGs),such as the Nintendo Wii(Nintendo,Taipei,China)and Xbox Kinect (Microsoft,Redmond,WA,USA),which can be played alone. AVGs require the player to engage in whole body movements to interactwithin a virtualworld,18,19and can increase time ofbeing physically active,18increase energy expenditure,18,20–23and can be enjoyable and motivating.24,25

AVGs may also have potential for skill improvement.26,27Yet the use of AVGs to target FMS in the TD population has had varying results.A randomized control trial using coaching(2 experimentalgroups:traditionalapproach(specificaly designed lesson plans focusing on FMS skills)orAVG use,such as Xbox Kinect play and skill coaching)found that post-test OC scores were greaterin both experimentalgroupsin comparison with the control group.28In contrast,2 other interventions in TD children using a play-based approach did notimprove actualorperceived OCskillproficien y.29,30Both studiesutilized a 2-group pre–post experimental design in which children,aged 4–829and 6–1030years old,engaged in AVG play once a week for 6 weeks.It is possible that in TD children,a play-based AVG intervention is not enough to promote skill development.Children may need to have a lowerbaseline skilllevelto be able to benefi from such an unstructured intervention.

The use of AVGs for skill development has also been investigated in non-TD children.One study demonstrated that AVG use allowed 17 children with cerebral palsy(aged around 10 years)to participate in PA and practice complex movement skills.31Similarly,a study with 14 children with spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy reported improvements in balance after a 3-week AVG intervention.32In children with ASD,2 American studies reported that AVGs had potential to decrease repetitive behaviors and improve executive functioning in children.33,34

To date,no research has investigated whether the use of AVGs can influenc the actual or perceived FMS of children with ASD.Therefore,this study aims to investigate whether a play-based AVG intervention can improve the actual or perceived OC skills of children with ASD relative to TD children. A secondary aim was to explore whether AVGs are a feasible intervention for children with ASD.Given children with ASD generally have lower FMS than TD children,it was hypothesized that the AVG intervention would have a greater impact on actual or perceived FMS in children with ASD relative to TD children.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Participants

Participants for the ASD group were recruited using purposive sampling through poster and newsletter advertisements displayed at established local referrers or through direct letters of invitation,sent to the parents of previous unrelated study participants who gave written informed consent to be contacted about future studies.Participants were required to meet the following inclusion criteria:(1)Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders(DSM)-V diagnosis of ASD or DSM-IV diagnosis of autistic disorder,Asperger disorder,or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specifie confi med by a pediatrician or psychologist,with an intelligence quotient(IQ)score of>70;(2)ASD range on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule;(3)in Grades 1–5 of primary school at the time of the study;and(4)no genetic conditions (i.e.,fragile X syndrome)or a condition that impacts their PA performance(i.e.,cerebral palsy).

A total of 11 children with ASD aged 6–10 years(in Grades 1–5 of primary school)had written permission from their parents to participate.Three of the participants were diagnosed with autistic disorder,3 with Asperger disorder,1 with pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specifie,and 4 with ASD.The mean IQ was 104.18±17.79,and the range was 73–142.

The TDsample wasdrawn from a previously completed study in which children did not improve their actual or perceived OC skills.30In the said study,informed written consentwasobtained from the school(via the principal)and parents.Children aged 6–10 years were randomly allocated into either an intervention (n=19)or control group(n=17).For the purpose of this study, only data from the intervention group were included.All procedures were carried out with ethical approval from Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee.

2.2.Measures

Demographic information of both sets of participants was collected at the time of consent through a parent survey asking for demographic information(including their relationship to the child,country ofbirth,language spoken athome,highestlevelof education attained,and current employment level),and also child participation in ball sports outside of school,ownership of an AVG console,time(min)of electronic leisure use per week, and diagnosisand full-scale IQ(ASD group only).Additionally, the ASD group completed any further required diagnostic assessments,including the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children35and theAutism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-2.36

The Test of Gross Motor Development-3(TGMD-3) assessed the participants’OC competence(2-hand strike,forehand strike,stationary dribble,catch,kick,overhand throw,and underhand throw)pre-and post-intervention according to the standard protocols.The TGMD37is a standardized measure designed to assess the gross motor abilities of children aged 3–11 years norm-referenced every 15 years,with the third edition due to be formally released in 2016.Each skill of the TGMD-3 has a number of components that need to be performed in order for the child to perform the skill competently. Each component of the skill is given a score of“1”if it is present or a score of“0”if absent.The 2 trials are summed for a total skill score.At completion,each skill score is added to get a subtest raw score.Assessment of children in the ASD group was filme and then scored at a later date by a trained observer. Children in the TD group were assessed live in the school setting by 2 trained observers.Before assessment,observers for both samples coded sample videos of children performing the TGMD-3 online as issued by the instrument developers and scored≥0.95 in terms of agreement with the pre-coded videos.

The 2 additional golf skill assessments,a golf swing and golf putt,were developed via a Delphi consultation,based on the format of the TGMD.These skill assessments have been shown to have acceptable intra-rater(intraclass correlation coefficien (ICC)=0.79,95%confidenc interval(CI):0.59–0.90)and test–retest reliability(ICC=0.60,95%CI:0.23–0.82).38This assessment was included due to the presence of the golf minigame in the intervention.

The Pictorial Scale of Perceived Movement Skill Competence(PMSC)for young children was utilized to assess children’s perceived competence in OC skills before and after the Xbox intervention period.The PMSC has face validity,good test–retest reliability,39and evidence of construct validity40for TD children.The PMSC involves the researcher showing the children a picture of a skill being performed“poorly”alongside an image of a child performing a skill“well”for the children to indicate which picture they believe best represent them(e.g.,“this child is pretty good at kicking,this child is not that good at kicking,which child is most like you?”).Within each chosen picture,the children were asked to specify their perceived competence corresponding to a 4-point Likert scale.For the pictures with the skill being performed well,options includereally goodrepresenting a score of 4 andpretty goodindicating a score of 3, whereas the pictures with the skill performed poorly had the following options:sort of goodrepresenting a score of 2 ornot that good atrepresenting a score of 1.The PMSC is reverseordered,where the skill being performed well changes from the leftto the rightofthe page,increasing the internalvalidity ofthe results by helping identify respondents who may simply point to one side of the page.41The skills corresponded to the skills performed in the TGMD-3 and the 2 golf skills.In the current ASD sample,the total perceived skill battery had good internal consistency using Cronbach’sα(0.82).

2.3.AVG intervention

The Xbox Kinect was used as the AVG intervention.The Kinect is a motion-sensing input device for the commercially available Xbox 360 console and does not require the player to hold or wear anything,allowing for a free range of movement.42Thegamesused forboth TDand ASDgroupswere KinectSports Season 1,Kinect Sports Season 2,and Sports Rivals(TD group only).For the TD group,Kinect Adventures(which provides limited OC opportunities)was offered in the fina week to maintain interest.Specifi mini-games(e.g.,baseball,golf, tennis,table tennis,soccer,bowling,volleyball,and football) were prioritized in order of preference based on their ability to provide practice of OC skills.

The ASD group was instructed to engage in the intervention for 45–60 min,3 times a week,for 2 weeks(6 sessions in total) within their own home.During the intervention phase,parents were asked to complete a game record form by detailing the date,start,and finis time of each gaming session and which games were played.The Xbox Kinect was set up in the participants’homes by the researchers after completion of preassessment.Children and their parents were provided with a short tutorial on the use of the Xbox Kinect,the prioritized game list,and a game record form,and were instructed on the desired frequency and duration of play.The children could choose what games to play from the prioritized game list.

The TD group participated in 50 min gaming sessions once a week during school lunchtimes(1:00 p.m.–1:50 p.m.)for 6 weeks(6 sessions in total).Two Xbox Kinect consoles were set up on 2 televisions in the school’s media room,with the sports games rotated each week.If a child was absent,he or she was asked to attend the next available session.A game record form was completed by the researchers to detail the amount of time (min)each child spent playing each sports game.30

At the completion of post-intervention testing,the parents of the children with ASD participated in an interview relating to their experience of the study,how their children responded to the intervention,and how feasible they believe using AVGs as an intervention would be for their family.Questions were drawn from the previous study(Appendix 1).30

2.4.Procedures

A 2-group pre-and post-test experimental design was utilized in which experimental and control groups both engaged in an AVG intervention and differed only in diagnosis(i.e.,an ASD group was compared with a TD comparison group).All ASD group data were collected within participants’own homes and TD group data at the participants’school.

2.5.Data analyses

All data analyses were completed using SPSS Version 22 (IBMCorp.,Armonk,NY,USA).Descriptive demographic data were firs presented.A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine whether in the ASD group there was a significan difference between pre-and post-intervention actual and perceived OC scores using a significanc level ofp<0.05.A series of general linear models,adjusting for potential confounding variables,30was used to assess if there was a significan difference between pre-and post-actual or perceived OC score of the children with ASD relative to the TD sample.Because of thelimited statistical power,these adjustments were performed in separate models rather than in 1 model.Each model had actual (or perceived)OC score as the outcome and group(TD orASD) as the predictor,and was adjusted for pre-intervention actual(or perceived)OC score and child age.Model 2 also adjusted for owning an AVGathome,whereas Model3 adjusted forthe sex of the child,Model 4 for previous participation in ball sports,and Model 5 for pre-score of either actual or perceived competency (whichever was not already included).For the feasibility data, interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim,and then descriptively analyzed in terms of practicality and feasibility of the intervention.

3.Results

3.1.Descriptive data

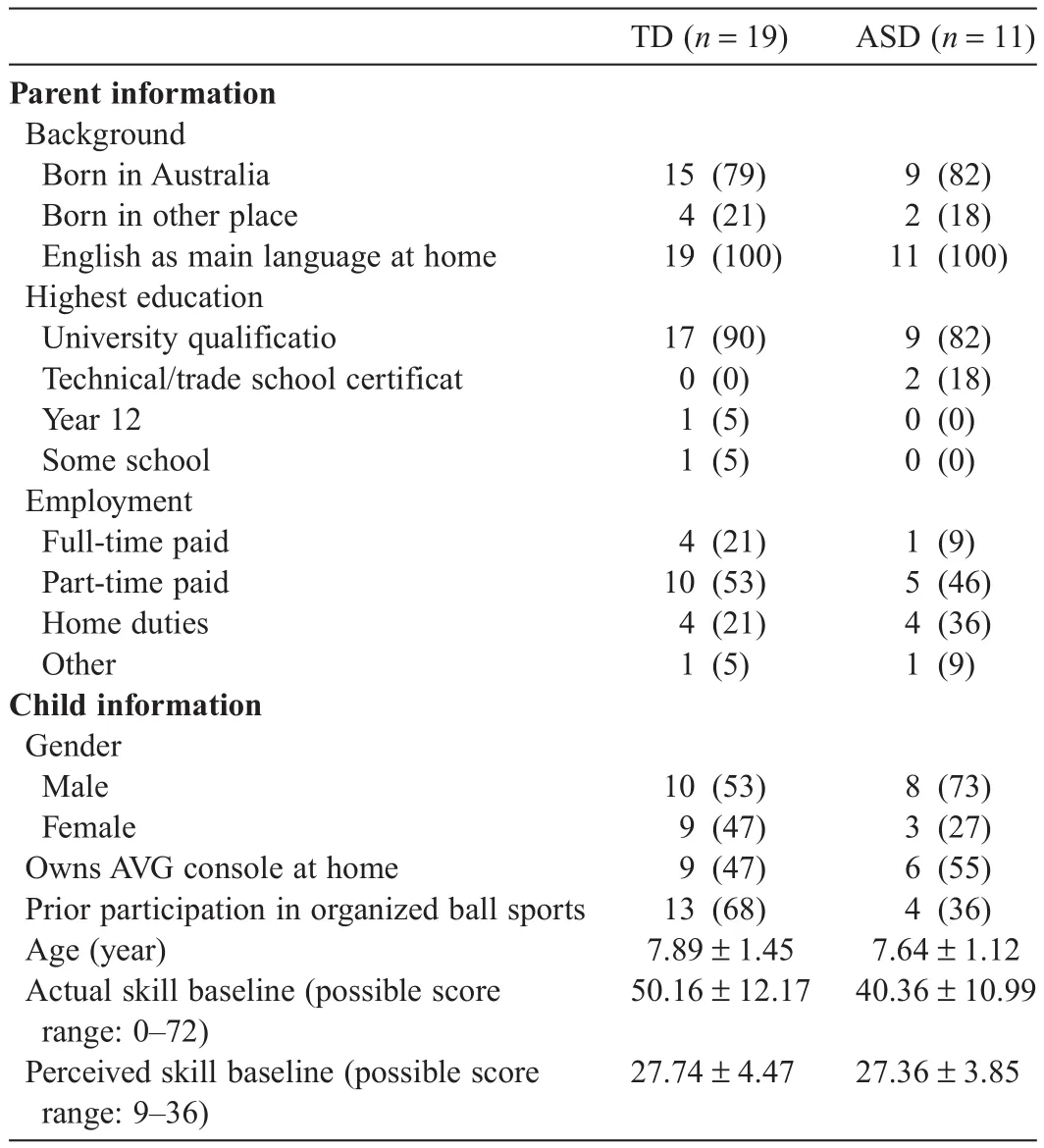

Table 1 presented the descriptive baseline information of both the ASD and TD groups.The demographics are similar, but the children with ASD have lower levels of actual skill and similar levels of perceived skill.

The total time spent using the Xbox Kinect during the intervention period was 59.3 h(5.4±1.6,mean±SD)for the ASD group and 76.2 h(4.00±0.58)for the TD group.For both the ASD and TD groups,most time was spent playing striking games(29.3 h and 54.3 h),followed by other OC sports games (20.9 h and 15.6 h)and non-OC games(9.1 h and 6.3 h).For the ASD group,the most commonly played game was tennis (8.4 h),followed by golf(7.8 h)and bowling(7.6 h),whereasfor the TD group the most commonly played games were golf (17.2 h),baseball(14.6 h),and table tennis(13.2 h).

Table 1 Demographic and baseline data of the TD and ASD children(n(%)or mean±SD).

Table 2 TGMD-3,golf skill,and perceived assessment pre-and post-score and signifi cance values for the ASD children(mean±SD).

3.2.OC skill improvement

The mean±SD values for the TGMD-3 and the golf skill assessment are presented in Table 2.The results from relatedsample Wilcoxon signed-rank test for the ASD group showed no significan increase between the pre-and post-intervention mean scores on the TGMD-3,the golf skill assessment,and the overall OC skill scores.However,perception of skill in the ASD group significanty increased by around 2 units(p=0.044).

The results from the general linear model analysis of the ASD group and TD group in terms of actual skills are presented in Table 3.The 5 models demonstrated no significan differences between the TD and ASD groups in actual skill(i.e.,on the row reflectin“Group(TD)”in Table 3,it is clear that there was no significanc for actual skill in any of the models).There were significan covariates in some models,that is,owning an AVG console(Model 2),participant age(older)(Model 4),and previous participation in ball sports(Model 4).

The results from the general linear model analysis of the ASD group and TD group when skill perception was the outcome are also presented in Table 3.Model 5(adjusting for pre-actual skill score)demonstrated a significan difference between the TD and ASD groups.Model 4(adjusting for participation in ball sports prior)approached significance The 3 other models demonstrated no significan difference between the TD and ASD groups in terms of skill perception.Gender (boy)was a significan positive covariate in Model 3.

3.3.Feasibility

The majority of the participants met the dose delivered; however,some parents suggested that the children became unenthusiastic afterplaying too long orwhen problemsbegan to arise,as in the following examples:She kept on dropping out before that,she was pretty much doing 20 min sessions(Participant 9).We found that 45 min was the ideal time,after that they would get too revved up,someone always got their feelings hurt(Participant 3).The 45 min was a bit long,just for his concentration we found it a bit long(Participant 2).

Table 3 Univariate analysis results assessing actual and perceived OC skill post-improvement after adjustment of potential covariates.

Some parents felt that smaller,more frequent sessions would better fi into the daily routine and keep the children engaged,as in the following examples:When we swapped the games around to change it up it was better,and he lasted a bit longer.He would have a bit of a break between games,which he needed(Participant 2).If you were to do 30 min before school,then extra on the weekend.It could definite y be built into the routine(Participant 1).Other parents,however,felt that because of busy schedules,less frequent sessions may f t better into the routine,as in the following example:That would be the absolute max(3 sessions per week),and that’s at a push(Participant 7).

The Xbox has the ability for individual play as well as multiplayer play.Parents identifie that the different types of play suited the different characteristics of their children.Two parents identifie that their children benefite from the individual play,as in the following example:Yeah it’s great,to not have to be dealing with other humans,and the game has obviously enough algorithms so that if he does“this”in any way shape or form,the volleyball will go over the net.It gives them the sense that their abilities are better.In real life at his age it probably it wouldn’t go over the net,but in the game you can get back in the game and not be losing losing losing...when he gets it wrong he gets in trouble with the other kids“...why can’t you do it,you’re not listening”so it gives that outlet(Participant 1).

This contrasted to the views of other parents who suggested that the multiplayer option benefite their child,as in the following example:And in terms of how he went,his highest engagement was when he was doing in a paired game,with someone else.To do it on his own,he just wouldn’t do it(Participant 7).

Family structure and rules were mentioned as a key reason their children were able to adhere to the 1 h time constraint per session.Parents indicated that this was something they had been developing with their children,as in the following example:If you took that off him a few years ago there would be a major meltdown.But he’s learnt that there’s always next time.If he gives it up when he’s meant to he’ll get it next time(Participant 5).

Parents had differing experiences with supervising their children.Some parents indicated that their children were able to play without supervision:The boys seemed to know how everything worked;I didn’t have to help them at all.We didn’t encounter anything he wasn’t capable of doing(Participant 6). He’s a wiz at all that kind of stuff,electronics so he picked it up in no time(Participant 1).

Some children needed small prompts,but overall were able to play unassisted:Yeah yeah,he wanted us to watch him.He wanted to show off....There were a few“MUM IT’S NOT WORKING”“Did you raise your hand?”“OH OKAY GOT IT”(Participant 1).

In contrast to this,1 parent explained that the child needed constant supervision to play:He needed total adult supervision the whole time,every session,our undivided attention(Participant 7).

Child and family characteristics were also mentioned as key reasons AVG play would not take time away from actual PA or to take over and become an obsession,as in the following examples:No,he would always rather the organized sports he does(Participant 2).Oh no,he and his sister still want to go outside and play,this wouldn’t stop them from doing that.I mean he does enjoy the Xbox but like last night they spent an hour outside on the trampoline together(Participant 10).

Parents mentioned that they noticed increased issues with play and frustration when their children were playing games where they did not understand the context:I think some of the things were that he’s never had any exposure to the games that were presented,like the individual sports.So he’s held a tennis racket once at school in PE...He’s never watched a game of tennis before,the same,baseball,American football,we’ve played mini golf but that’s very different to a bigger swing.So I think there was a lack of context,so we needed to explain everything,which is why we had to be in the room(Participant7).

Parents also suggested that AVG use might increase their children’s willingness to give the game a go in a real-life situation,as in the following examples:Yeah I was good at that lets give it a go...I think that’s part of the confidenc thing. And also an understanding of what the game is,what it looks like,how it works and the rules too(Participant 2).Because ofthe practice(at table tennis)...Extrapolate that out to the totem tennis,which means he can play totem tennis at someone’s house who already has one and had practice...yep direct correlation,table tennis,social skills,and social interaction.Because of the independent,single person practice,then move on to the multi person environment(Participant 1).Oh yeah,he’s already asked me to sign him up to a tennis program! Just from giving it a go and loving it...Yep he wants to do that now which I’m going to take full advantage of(Participant 10).

One parent of siblings also mentioned that it might be an appropriate alternative for children who do not like to play real-life sports:When they’re just going crazy we’ll send them out to the trampoline but we don’t do a lot of like taking them out for a walk or a bike ride because they have a meltdown halfway through and you can’t get them home!So the things that are home based are a lot easier to do for us(Participants 8 and 9).

As well as having the potential to increase PA levels,parents noted that it might be a way of reducing sedentary screen time: I actually think they spent less time on their other games,like the iPad or computer games...that’s where it took time from (Participants 3 and 4).He’s pretty obsessed with electronics... He gets a lot of device time and I reckon he would rather the XBox time over the iPad(Participant 1).

Parents noted some positive elements ofAVGs that increased their children’s ability to play,such as the visual elements,as in the following examples:But the little green man at the bottom and the highlighted bits—the arm movements.That is just ASD to a T.Showing,this is where this arm has to go and this is what it has to do,yeah.Cause I think a lot of the times when they’re being given verbal instruction,it’s just“blah blah blah blah”–in one ear out the other(Participant 1).Yeah,he was copying that(the visual cues),it was getting his attention.Better than written instructions because he would have just skipped over that.He is not interested in instructions(Participant 5).

4.Discussion

This study found no significan improvement in the actual OC skill scores of children with ASD who participated in an Xbox Kinect gaming program for 45–60 min,3 times a week for 2 weeks.Children with ASD did,however,improve their perceptions of competence,and also when compared with the TD children.

As far as the authors are aware,this is the firs study investigating the impact of AVGs on the OC skills of children with ASD.It was hypothesized that children with ASD may have more potential to improve their skills through AVG play compared with TD children as their FMS is generally lower.This hypothesis was not supported as the children with ASD did not improve their actual OC skills.Similarly,a recent study that investigated the influenc of playing Nintendo Wii on movement skills of 21 children aged 9–12 at risk of developmental coordination disorder also found no significan improvements.43

The currentstudy was designed to investigate whether“play”improved OC skill.Therefore,children were not provided with instruction and coaching.In contrast,each session in the AVG program implemented by Vernadakis et al.28with TD children was led by an experienced motor skill instructor who delivered specifi lesson plans based on the emerging developmental motor need of the participants and provided feedback on the correctperformance ofeach targeted skill.Thisisimportantasit suggests thatAVG“play”alone may not be enough to influenc the acquisition of skill in eitherTD orASD children,unless it is combined with a structured movement skill intervention.

The“dose”of the intervention program used by the studies may also be a possible reason for the difference in results.The intervention by Vernadakis et al.28in TD children was an 8-week program consisting of 30 min sessions,twice a week (480 min in total),whereas this study had a mean total dose of 5.4 h(323 min).It is possible that this time was not sufficien enough to produce a significan change in OC skills.

Another plausible explanation for the lack of impact on OC skill is that AVGs may not provide enough opportunity to correctly perform the specifi movement components assessed in each of the OC skills.This study did not assess the movement patterns performed by participants with ASD during AVG play. However,during the previousstudy from which the intervention group TD data were drawn,30observations indicated that correct execution of skill components was only present 40%of the time during baseball,tennis,and table tennis,10%–20%of time for golf,and approximately 5%ofthe time forsoccer.44Itispossible that the children with ASD displayed similar movements,limiting the opportunity for the development of OC skills.

Interestingly,whereas actual OC skill did not improve,child self-perceptions did.A mean increase of 2 points was seen in perceived competence for children after the intervention,but only in the children with ASD.This can be interpreted as children increasing self-perception from“sort of good”to“pretty good”on 2 skills(e.g.,kick and catch).Because children with higher perceived competence have a higher likelihood of engaging in or continuing a behavior or activity,12increasing the perceived competence of children with ASD from “sort of good”to“pretty good”in a skill has the potential to increase their engagement in mastery attempts of activities involving this skill,and may subsequently increase PA levels and drive the acquisition of actual competence.This was also reflecte in the parent comments where parents had noted that their children were now interested in trying new sports and activities(e.g., tennis)as a result of building up confidenc by playing the AVG game.Other studies show support of the ability forAVG play to increase non-TD child physical self-perception.Three sessions a week of a 10 min Nintendo Wii intervention for 4 weeks in 18 children(aged 7–10)with movement difficultie showed an increase in overall self-perceived ability in a range of movement tasks.45Similarly,a 16-week intervention where 21 children played Sony PlayStation 3(Sony Corp.,Tokyo,Japan)with Move and Eye motion input devices and an Xbox 360 for a minimum of 20 min 4 or 5 days every week increased the perceived competence of children with developmental coordination disorder.43AVG use may,therefore,have the ability to increase perceived competence of non-TD children,such as those with ASD.

We also found that AVG use was a feasible intervention.All children completed the intervention.Parents indicated thatAVGs would be able to be delivered practically considering family time and commitment,and the intervention was generally responded to well by the parents.There were positive aspects of AVG use that parents noted,such as fl xibility of game play,appeal to their children’s interests and ability,as well as the potential to increase actual PA and reduce sedentary media time.However,barriers to AVG use were also expressed, such as lack of context of sporting games and supervision of the children.

The study strengths were the pre-and post-test experimental design and the use of valid and reliable measures for actual and perceived OC skills.The main limitation is the small sample size of the ASD group,limiting the generalizability of the results.However,as a“proof-of-concept”study,and when put into the context of other research into children with ASD,which commonly utilize single-group designs and small sample sizes,33,34the current study is still noteworthy.A potential limitation in terms of comparability of the samples is that the TD children had their 6 sessions over 6 weeks,whereas the children with ASD had their sessions over a fortnight.Although all children experienced a similar frequency of dose(i.e.,6 sessions ofAVG play),the TD children averaged less time than the children with ASD(4 h of play compared with 5.4 h).It must be noted though that the children with ASD were not directly observed while playing(data gained from parent proxy report), and hence their actual dose may have been overestimated and thus in reality could be more similar to that of the TD children. PA intensity during game play was also not recorded.Hence,it was not known how intensity of the activity may have influ enced any intervention effects.

5.Conclusion

Overall,this study did not fin any significan increase in OC skills following a 2-week intervention of playing Kinect Sports on the Xbox Kinect,but did fin an improvement in ASD children’s perceptions of their own motor skills.These finding suggest that the use of AVGs(45–60 min,3 times a week for 2 weeks)as a play-based intervention to improve OC skills may not provide enough opportunity for children to perform the correct movement patterns to influenc OC skill when delivered in the current format.An AVG program may be more successful when used for a longer period of time or when incorporated in a therapy session within a structured environment,rather than for“play”in an unstructured in-home environment.However, play of sports-based AVG games may influenc ASD children’s perceptions of their skill ability,which could lead to positive active behavior.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the children and parents who participated in this research and the Department of Education Victoria. Barnett is supported by an Alfred Deakin Fellowship.This work was supported by internal university funding.This research did not receive any specifi grant from funding agencies in the public,commercial,or not-for-profi sectors.

Authors’contributions

JE carried out the data collection and analysis and drafted the manuscript;SJ carried out the data collection and analysis and contributed to the manuscript;NJR participated in its design and coordination and helped draft the manuscript;LMB and TM conceived of the study,participated in its design and coordination,and helped draft the manuscript.All authors have read and approved the fina version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

None of the authors declare competing financia interests.

Appendix 1

Parent questions

Could I ask you to tell me about your child’s experiences with the Xbox Kinect,and your attitude towards it?

Can you tell me a bit more about what you think are the good and bad things about your child using these active electronic games?

How did your child respond to the 45 min to 1 h time frames? For how long would your child play one of these active games?

Do you think that playing these games affects your child’s willingness and ability to do the activity in real life(e.g., playing Xbox soccer and then playing soccer in real life?)

Do you think that active electronic gaming is a feasible way of improving your child’s motor skills?What do you think of this idea?

How do you think your child has enjoyed this intervention?

Considering your family circumstances and commitments,how often do you think it would work for your child to play the Xbox per week?

How often does your child participate in extracurricular sporting activities?Do you think use of these sorts of games would impact on your child’s other activities?If so,in what way?

1.American Psychiatric Association.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders(DSM-5®).Washington DC:American Psychiatric Association;2013.

2.Janssen I,LeBlanc AG.Systematic review of the health benefit of physical activity and fitnes in school-aged children and youth.Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2010;7:1–16.

3.Sowa M,Meulenbroek R.Effects of physical exercise on autism spectrum disorders:a meta-analysis.Res Aut Spec Dis 2012;6:46–57.

4.Australian Bureau of Statistics.Australian health survey:physical activity. Canberra,ACT:Australian Bureau of Statistics;2013.p.2011–2.

5.Srinivasan SM,Pescatello LS,Bhat AN.Current perspectives on physical activity and exercise recommendations for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders.Phys Ther 2014;94:875–89.

6.Tyler K,Cook NM,MacDonald M.Physical activity and children with disabilities:viable resources available for community health professionals. Palaestra 2014;28:17–22.

7.Must A,Phillips SM,Curtin C,Anderson SE,Maslin M,Lividini K,et al. Comparison of sedentary behaviors between children with autism spectrum disorders and typically developing children.Autism 2013;18:376–84.

8.Staples KL,Reid G.Fundamental movement skills and autism spectrum disorders.J Autism Dev Disord 2010;40:209–17.

9.Hardy LL,Reinten-Reynolds T,Espinel P,Zask A,Okely AD.Prevalence and correlates of low fundamental movement skill competency in children. Pediatrics 2012;130:390–8.

10.Barnett L,Van Beurden E,Morgan PJ,Brooks LO,Beard JR.Childhood motor skill proficien y as a predictor of adolescent physical activity.J Adolesc Health 2009;44:252–9.

11.Babic MJ,Morgan PJ,Plotnikoff RC,Lonsdale C,White RL,Lubans DR. Physical activity and physical self-concept in youth:systematic review and meta-analysis.Sports Med 2014;44:1589–601.

12.Stodden DF,Goodway JD,Langendorfer SJ,Roberton MA,Rudisill ME, Garcia C,et al.A developmental perspective on the role of motor skill competence in physical activity:an emergent relationship.Quest 2008;60:290–306.

13.Liu T,Hamilton M,Davis L,ElGarhy S.Gross motor performance by children with autism spectrum disorder and typically developing children on TGMD-2.J Child Adolesc Behav 2014;2:1–4.

14.Menear KS,Neumeier WH.Promoting physical activity for students with autism spectrum disorder:barriers,benefits and strategies for success.J Phys Educ Recreat Dance 2015;86:43–8.

15.Scalli L,Bolling KRC,Minio A,Rice R.The impact of motor delays on social skill development within the autism spectrum disorder population. LINK 2015;35:11.

16.Papadopoulos N,McGinley J,Tonge B,Bradshaw J,Saunders K,Murphy A,et al.Motor proficien y and emotional/behavioural disturbance in autism and Asperger’s disorder:another piece of the neurological puzzle? Autism 2011;16:627–40.

17.Todd T,Reid G.Increasing physical activity in individuals with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 2006;21:167–76.

18.Daley AJ.Can exergaming contribute to improving physical activity levels and health outcomes in children?Pediatrics 2009;124:763–71.

19.Mears D,Hansen L.Technology in physical education article#5 in a 6-part series:active gaming:definitions options and implementation.Strategies 2009;23:26–9.

20.Graf DL,Pratt LV,Hester CN,Short KR.Playing active video games increases energy expenditure in children.Pediatrics 2009;124:534–40.

21.Peng W,Lin J-H,Crouse J.Is playing exergames really exercising?A meta-analysis of energy expenditure in active video games.Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2011;14:681–8.

22.Sween J,Wallington SF,Sheppard V,Taylor T,Llanos AA,Adams-Campbell LL.The role of exergaming in improving physical activity:a review.J Phys Act Health 2014;11:864.doi:10.1123/jpah.2011-0425

23.Sun H.Operationalizing physical literacy:the potential of active video games.J Sport Health Sci 2015;4:145–9.

24.Gao Z,Podlog L,Huang C.Associations among children’s situational motivation,physical activity participation,and enjoyment in an active dance video game.J Sport Health Sci 2013;2:122–8.

25.Gao Z,Zhang T,Stodden D.Children’s physical activity levels and psychological correlates in interactive dance versus aerobic dance.J Sport Health Sci 2013;2:146–51.

26.Barnett LM,Bangay S,McKenzie S,Ridgers ND.Active gaming as a mechanism to promote physical activity and fundamental movement skill in children.Front Public Health 2013;1:74.doi:10.3389/fpubh. 2013.00074

27.Barnett L,Hinkley T,Okely AD,Hesketh K,Salmon J.Use of electronic games by young children and fundamental movement skills?Percept Mot Skills 2012;114:1023–34.

28.Vernadakis N,Papastergiou M,Zetou E,Antoniou P.The impact of an exergame-based intervention on children’s fundamental motor skills. Comput Educ 2015;83:90–102.

29.Barnett LM,Ridgers ND,Reynolds J,Hanna L,Salmon J.Playing active video games may not develop movement skills;an intervention trial.Prev Med Rep 2015;2:673–8.

30.Johnson TM,Ridgers ND,Hulteen RM,Mellecker RR,Barnett LM.Does playing a sports active video game improve young children’s ball skill competence?J Sci Med Sport 2015;19:432–6.

31.Howcroft J,Klejman S,Fehlings D,Wright V,Zabjek K,Andrysek J,et al. Active video game play in children with cerebral palsy:potential for physical activity promotion and rehabilitation therapies.Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:1448–56.

32.Jelsma J,Pronk M,Ferguson G,Jelsma-Smit D.The effect of the Nintendo WiiFiton balance controland gross motorfunction ofchildren with spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy.Dev Neurorehabil 2013;16:27–37.

33.Anderson-Hanley C,Tureck K,Schneiderman RL.Autism and exergaming:effects on repetitive behaviors and cognition.Psychol Res Behav Manag 2011;4:129–37.

34.Hilton CL,Cumpata K,Klohr C,Gaetke S,Artner A,Johnson H,et al. Effects of exergaming on executive function and motor skills in children with autism spectrum disorder:a pilot study.Am J Occup Ther 2014;68: 57–65.

35.Wechsler D.Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-WISC-IV.New York, NY:Psychological Corporation;2003.

36.Lord C,Rutter M,DiLavore P,Risi S,Gotham K,Boshop S. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule.2nd ed.(ADOS-2)manual (part 1):modules.Torrance,CA:Western Psychological Services; 2012.p.1–4.

37.Ulrich DA.Test of Gross Motor Development-2.Austin,TX:Prod-Ed; 2000.

38.Barnett LM,Hardy LL,Brian AS,Robertson S.The development and validation of a golf swing and putt skill assessment for children.J Sports Sci Med 2015;14:147–54.

39.Barnett LM,Ridgers ND,Zask A,Salmon J.Face validity and reliability of a pictorial instrument for assessing fundamental movement skill perceived competence in young children.J Sci Med Sport 2015;18: 98–102.

40.Barnett LM,Vazou S,Abbott G,Bowe SJ,Robinson LE,Ridgers ND,et al. Construct validity of the Pictorial Scale of Perceived Movement Skill Competence.Psychol Sport Exerc 2016;22:294–302.

41.Heatherton TF,Wyland CL,Lopez S.Assessing self-esteem.In:Lopez SJ, Snyder CR,editors.Positive psychological assessment:a handbook of models and measures.Washington,DC:APA;2003.p.219–33.

42.Kamel-Boulos MN.Xbox 360 Kinect exergames for health.Games Health J 2012;1:326–30.

43.Straker L,Howie E,Smith A,Jensen L,Piek J,Campbell A.A crossover randomised and controlled trial of the impact of active video games on motor coordination and perceptions of physical ability in children at risk of developmental coordination disorder.Hum Mov Sci 2015;42:146–60.

44.Hulteen RM,Johnson TM,Ridgers ND,Mellecker RR,Barnett LM. Children’s movement skills when playing active video games.Percept Mot Skills 2015;121:767–90.

45.Hammond J,Jones V,Hill EL,Green D,Male I.An investigation of the impact of regular use of the Wii Fit to improve motor and psychosocial outcomes in children with movement difficulties a pilot study.Child Care Health Dev 2014;40:165–75.

Received 1 May 2016;revised 16 July 2016;accepted 5 September 2016 Available online 1 December 2016

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

*Corresponding author.

E-mail address:lisa.barnett@deakin.edu.au(L.M.Barnett)

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2016.09.004

2095-2546/©2017 Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

杂志排行

Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Building a healthy China by enhancing physical activity: Priorities,challenges,and strategies

- Exercise is...?:A commentary response

- Exergaming:Hope for future physical activity?or blight on mankind?

- Running slow or running fast;that is the question: The merits of high-intensity interval training

- Fairness in Olympic sports:How can we control the increasing complexity of doping use in high performance sports?☆

- Fight fir with fire Promoting physical activity and health through active video games