花生胚小叶对卡那霉素的敏感性研究

2016-12-13王凤欢何美敬杨鑫雷崔顺立穆国俊侯名语刘立峰

王凤欢,何美敬,杨鑫雷,崔顺立,穆国俊,侯名语,刘立峰

(教育部华北作物种质资源实验室/河北省作物种质资源重点实验室/河北农业大学农学院,河北 保定 071001)

花生胚小叶对卡那霉素的敏感性研究

王凤欢,何美敬,杨鑫雷,崔顺立,穆国俊,侯名语,刘立峰*

(教育部华北作物种质资源实验室/河北省作物种质资源重点实验室/河北农业大学农学院,河北 保定 071001)

卡那霉素是植物遗传转化中常用的一种筛选剂。研究花生胚小叶对卡那霉素的敏感性,对建立利用卡那霉素筛选花生遗传转化的有效体系具有重要意义。以3个不同基因型花生弗落蔓生、麻油1-1和濮花23号为试验材料,通过计算胚小叶黄化率、丛生芽诱导率和生根数等,并观察外植体的生长状态,研究不同浓度卡那霉素对胚小叶生长发育、丛生芽分化和丛生芽生根阶段的影响,以期确定3个品种胚小叶各个分化阶段的适宜筛选浓度。结果表明,不同基因型花生对卡那霉素的敏感性不同,弗落蔓生、麻油1-1和濮花23号胚小叶丛生芽分化筛选浓度依次为: 150mg/L、100mg/L和50mg/L;丛生芽生根筛选浓度分别为:弗落蔓生20mg/L、麻油1-1 20mg/L和濮花23号10mg/L。本研究筛选到不同品种胚小叶丛生芽分化和丛生芽生根阶段的适宜卡那霉素浓度,为以花生胚小叶为外植体的花生遗传转化阳性植株的筛选奠定了基础。

花生;卡那霉素;基因型;敏感性

花生在我国经济发展中占有重要地位,是我国重要的经济作物和油料作物[1]。随着基因工程的发展,利用转基因技术提高作物产量和品质已成为重要的作物育种手段。近几年在花生遗传转化中常用的转化方法主要是农杆菌介导法[2]。为了快速高效地获得转化体,转化过程中利用抗生素进行筛选是必不可少的。

目前,在植物转基因初步检测中使用的筛选剂主要有抗生素类和氨基酸类,其中以抗生素类应用较多。卡那霉素是目前植物遗传转化中应用最广泛的一种筛选剂[3-4],已用于多种双子叶植物的遗传转化[5-11]。卡那霉素使用的浓度因不同品种或相同品种的不同外植体类型而不同[12-16]。如果卡那霉素浓度太低,则不能充分抑制或杀死未转化的细胞,从而造成假阳性率过高;若卡那霉素浓度过高,又抑制甚至杀死转化细胞,导致不能得到足量的转基因植株。为了使卡那霉素对植物材料具有很好的筛选作用,需要在目的基因转化之前,对所研究的材料进行选择性抗生素敏感性试验。

在花生的遗传转化研究中有关卡那霉素的敏感性筛选多见于单个生长阶段的研究[12,17-18],而对卡那霉素在花生外植体整个生长阶段敏感性的系统筛选研究报道较少[19]。本研究以3个不同基因型的花生胚小叶为外植体,研究其整个发育期阶段在添加有不同浓度卡那霉素的培养基中的生长情况及状态,明确各个品种胚小叶外植体在各发育阶段对卡那霉素的适宜筛选浓度,以期为进一步花生的遗传转化和阳性植株的筛选提供试验依据。

1 材料与方法

1.1 材 料

供试花生(ArachishypogaeaL.)品种为弗落蔓生、麻油1-1和濮花23号,均来自河北农业大学花生研究所种质资源库。胚小叶萌发培养基:MSB5+30 mg/L蔗糖+6.95 mg/L琼脂,pH5.8;丛生芽诱导培养基: MSB5+30 mg/L蔗糖+6.95 mg/L琼脂+6 mg/L 6-BA+0.2 mg/L NAA,pH5.8;芽伸长培养基:MSB5+30 mg/L蔗糖+6.95 mg/L琼脂+4 mg/L 6-BA+2 mg/L GA3+0.2 mg/L NAA,pH5.8;生根培养基:1/2 MSB5+30 mg/L蔗糖+6.95 mg/L琼脂+1 mg/L NAA+0.2 mg/L IAA,pH 5.8。

1.2 方 法

1.2.1 花生无菌苗的培养 选择大小一致的无病斑且种皮完好的花生种子,用无菌水冲洗1~2次后用吸纸吸干,先后浸于75%酒精中1 min、0.1% HgCl2溶液中15 min, 进行表面消毒,再用无菌水漂洗4~5次,剥去种皮,浸泡于无菌水中6~7 h之后剥取胚小叶外植体将其接种于萌发培养基上培养。取培养 8 d 的胚小叶外植体,接种于丛生芽诱导培养基上,诱导丛生芽,待丛生芽长1mm左右,将其转入伸长培养基中生长,每21~25 d继代一次,直到丛生芽伸长至4~5 cm 后,切下伸长苗转入生根培养基中进行生根培养。培养过程中的培养条件均为温度(26±0.5)℃,光照16 h/d,光照强度18.75~25.00 μmol/(m2·s)。

1.2.2 花生胚小叶分化的卡那霉素选择压的确定 取萌发 8 d 的花生胚小叶作为外植体,接种于含卡那霉素(Kan)的丛生芽诱导培养基上进行敏感性试验,卡那霉素的浓度梯度为:0 mg/L、50 mg/L、100 mg/L、150 mg/L和200 mg/L共5个处理,培养25 d 后调查生长情况。

1.2.3 花生胚小叶丛生芽伸长的卡那霉素选择压的确定 取生长到1mm左右的无菌丛生芽接到含有卡那霉素的伸长培养基中,卡那霉素的浓度梯度分别为:0 mg/L、50 mg/L、100 mg/L、150 mg/L 和200 mg/L 5个处理,培养25 d后调查生长情况。

1.2.4 花生胚小叶丛生芽生根的卡那霉素选择压的确定 取无菌的待生长到4~5 cm左右的伸长苗接到含有卡那霉素的生根培养基中,卡那霉素的浓度梯度分别为:0 mg/L、10 mg/L、20 mg/L、30 mg/L、40 mg/L和50 mg/L,培养25 d后调查生根情况。

1.3 数据统计与分析

丛生芽诱导率=(诱导出丛生芽的外植体/接种总外植体数)×100%

黄化率=(诱导出黄化的外植体数/接种总外植体数)×100%

全部数据采用Microsoft Excel 2003与统计分析软件SPSS Statistics 17.0进行分析。

2 结果与分析

2.1 卡那霉素对花生胚小叶生长发育的影响

由图1和图2可以看出,花生弗落蔓生胚小叶外植体的三个生长发育时期对卡那霉素的敏感性存在差异,卡那霉素浓度在50 mg/L时,胚小叶外植体愈伤发育时期的黄化率达到50%,愈伤组织发白,叶片黄化,后期将未黄化的组织转入低浓度的卡那霉素培养基中也未能分化出芽点,愈伤组织体积没有增大,且颜色逐渐变为黄褐色至死亡。丛生芽分化时期和伸长苗生长时期的黄化率分别为37.04%和26.67%,组织正常生长没有明显变化。卡那霉素浓度100 mg/L时,胚小叶外植体的伸长苗生长对卡那霉素较其他两个时期敏感,生长状态表现为整个伸长苗只有最顶端叶片为淡绿色,叶柄和茎都已黄化至白化。卡那霉素浓度在150 mg/L和200 mg/L时,花生胚小叶外植体的三个生长时期的黄化率都达到100%。该结果表明,胚小叶外植体在它的不同生长发育时期对卡那霉素的敏感程度是存在差异的。因此以卡那霉素作为筛选标记时,在胚小叶培养的不同时期阶段应选择不同的卡那霉素适宜筛选浓度,避免浓度过高或过低而影响筛选效果。

图 1 卡那霉素对胚小叶生长发育的影响Fig. 1 The effect of kanamycin on leaflet development

图 2 卡那霉素对胚小叶生长发育的影响Fig. 2 The effect of kanamycin on leaflet development注:1~5:卡那霉素的浓度依次为:0 mg/L、50 mg/L、100 mg/L、150 mg/L和200 mg/L;A~C:花生胚小叶不同生长发育阶段依次为:愈伤阶段、丛生芽阶段和伸长阶段。Note: 1~5: The concentration of kanamycin was 0 mg/L, 50 mg/L, 100 mg/L, 150 mg/L and 200 mg/L, successively;A~C: The different growth stages of peanut leaflets were callus stage, clustered shoots stage and elongation stages, successively.

2.2 卡那霉素对不同花生基因型胚小叶分化的影响

附表和图3表明,不同浓度的卡那霉素对同一品种花生的丛生芽分化的影响具有显著性差异,随着卡那霉素浓度的提高,丛生芽率逐渐降低,说明卡那霉素能够抑制花生丛生芽的生长。不同品种的花生胚小叶对卡那霉素的敏感性差异较大。当未添加卡那霉素时,3个品种都有较好的丛生芽率;当卡那霉素的浓度为50 mg/L时,濮花23号的胚小叶丛生芽的分化明显受到抑制,胚小叶的丛生芽率降为53.33%,而弗落蔓生的胚小叶的丛生芽率为87.5%,麻油1-1的胚小叶的丛生芽率为85.83%;当卡那霉素的浓度增加为100 mg/L时,麻油1-1和濮花23号的胚小叶的丛生芽率降为51%以下,未分化丛生芽的胚小叶发生黄化转为白化最后死亡。弗落蔓生对卡那霉素的敏感性较前2个品种低,在100 mg/L卡那霉素的选择压力下,胚小叶的丛生芽率仍在70%以上;当卡那霉素的浓度达到200 mg/L时,其抑制效应达到最大,3个品种的丛生芽率都下降到50%以下。由于卡那霉素随着浓度的增高对胚小叶的前期生长有明显的抑制作用,因此在胚小叶生长初期不宜用过高的卡那霉素浓度以免影响后期的转化植株的生长,同时不同品种对卡那霉素的敏感性不同,因此以丛生芽率50%为标准来确定各品种的初期最适筛选浓度。由此得出,花生胚小叶丛生芽分化的卡那霉素的适宜筛选浓度:弗落蔓生为150 mg/L,麻油1-1为100 mg/L,濮花23号为 50 mg/L。

附表 卡那霉素对不同基因型花生丛生芽诱导率的影响 (%)

注:同列不同大写字母表示差异显著水平 (p<0.01)。

Note: The capital letter in the same column indicated the significance of difference at 0.01 level.

图 3 卡那霉素对不同基因型花生丛生芽的影响Fig. 3 The effect of kanamycin on clustered shoots of different genotypes of peanut注:1~5:卡那霉素的浓度依次为:0 mg/L、50 mg/L、100 mg/L、150 mg/L和200 mg/L;A~C:花生品种依次为:弗落蔓生、麻油1-1和濮花23号。Note: 1~5: The concentration of kanamycin was 0 mg/L, 50 mg/L, 100 mg/L, 150 mg/L and 200 mg/L,successively; A~C: Peanut genotypes were Fuluomansheng, Mayou1-1 and Puhua23, successively.

2.3 对不同花生基因型胚小叶丛生芽生根的影响

当花生伸长苗转入含有不同卡那霉素浓度的生根培养基中,经过5 d的培养,未添加卡那霉素的伸长苗开始生根,而添加卡那霉素的培养基中的伸长苗无一生根。经过10 d的培养之后含有10 mg/L和20 mg/L卡那霉素的培养基中的伸长苗开始生根。随着培养时间的增加,生长在未添加卡那霉素的培养基中的根越来越长,平均生根数量越来越多,而在含有卡那霉素的培养基中的伸长苗随着培养基中卡那霉素浓度的增加,平均生根数量和平均根长度显著下降(图4~5)。从图6可以看出,不同的基因型之间存在明显差异,当卡那霉素浓度为0 mg/L时,三个品种的根系生长发达,植株生长快。卡那霉素浓度增加到10 mg/L时,濮花23号的生根数量明显下降,而麻油1-1和弗落蔓生变化不明显;卡那霉素浓度为20 mg/L时,濮花23号的伸长苗不能生根,弗落蔓生的伸长苗基部有少许的根长出,根细小而脆弱,麻油1-1的伸长苗能长出明显根系;卡那霉素浓度为30 mg/L、40 mg/L时,三个基因型花生伸长苗不能生根,逐渐变黑,植株枯萎而死亡。由此得出,不同品种花生胚小叶丛生芽生根的卡那霉素的适宜筛选浓度为:弗落蔓生为20mg/L,麻油1-1为20 mg/L ,濮花23号为 10 mg/L。

图 4 卡那霉素对不同基因型根系长度的影响

图 6 卡那霉素对不同基因型花生丛生芽生根的影响Fig. 6 The effect of kanamycin on rooting of clustered shoots of different genotypes of peanut注:1~5:卡那霉素的浓度依次为:0 mg/L、10 mg/L、20 mg/L、30 mg/L和40mg/L;A~C:花生品种依次为:麻油1-1、弗落蔓生和濮花23号。Note: 1~5: The concentration of kanamycin was 0 mg/L, 10 mg/L, 20 mg/L, 30 mg/L and 40 mg/L, successively.A~C: Peanut genotypes were Mayou1-1, Fuluomansheng and Puhua23, successively.

3 讨 论

适宜的抗生素筛选浓度是提高花生遗传转化效率的影响因素之一,筛选浓度过高或过低均会影响转化体的筛选效果。卡那霉素是植物遗传转化中常见的一种筛选剂,其使用的浓度因不同植物类型或相同品种的不同外植体类型而不同。张春涛等[5]研究表明,不同的大豆品种有其适宜的卡那霉素筛选浓度,子叶节分化时,垦农18为 40 mg/L、绥农14 和垦农4为 60 mg/L;张静妮等[11]发现不同的紫花苜蓿品种在下胚轴分化阶段,不同品种选择压分别为秘鲁50 mg/L、富平和甘农3号60 mg/L;不同的烟草品种在叶片分化和生根阶段,不同品种适宜的卡那霉素筛选浓度也有所不同[10]。可见,不同植物或同一植物不同品种以及同一品种外植体不同生长阶段之间对卡那霉素的敏感性均表现出显著差异,导致卡那霉素在使用浓度的筛选时相差很多。因此对试验中将要用于转化的外植体进行系统筛选在植物转基因研究中是非常必要的。

张甲佳等[12]以花生胚小叶外植体作为材料,对不同卡那霉素浓度下的不同花生品种的敏感性研究表明,在愈伤发育时期,D16、花育22和鲁花11三个品种的卡那霉素的临界浓度分别为100 mg/L、200 mg/L和150 mg/L。胡晓君[19]以花生胚小叶外植体为材料,研究卡那霉素对再生芽丛的影响,结果表明,对于花生品种丰花1号和丰花2号,400 mg/L的卡那霉素浓度是转基因再生芽丛和非转基因再生芽丛筛选的临界浓度。本试验研究了花生胚小叶对卡那霉素的敏感性,表明不同花生基因型之间存在明显差异结果,与以上研究相一致,但本研究系统地从胚小叶外植体的整个生长阶段进行研究,通过对生长状态的观察综合考虑后确定不同生长阶段所使用的卡那霉素的适宜浓度。研究结果为,胚小叶丛生芽分化的卡那霉素筛选浓度:弗落蔓生为150 mg/L,麻油1-1为100 mg/L,濮花23号为50 mg/L;丛生芽生根的卡那霉素筛选浓度:弗落蔓生为20 mg/L,麻油1-1为20 mg/L,濮花23号为10 mg/L。

根据本试验,通过观察外植体的生长状况,在用卡那霉素进行筛选转化时,适宜的继代时间应尽量控制在25 d,若培养时间过长,由于培养基的营养消耗,再生芽会出现生长不正常;同时由于卡那霉素长期处于培养基中,活性会下降,从而使非转化芽也生长起来,因此在转化研究中应在适当的筛选时间内进行外植体及转化芽的转移,这不仅可以使转化芽正常生长,同时也可避免在继代过程中有非转化芽出现,影响筛选效果[20]。

本研究筛选到不同花生品种胚小叶丛生芽分化和丛生芽生根阶段的适宜卡那霉素浓度,为以花生胚小叶为外植体的花生遗传转化提供理论基础,应用于花生遗传转化中可以有效提高转化效率。

[1] 潘月红,钱贵霞. 中国花生生产现状及发展趋势[J]. 中国食物与营养,2014,20(10):18-21.

[2] 黄冰艳,张新友,苗利娟,等. 花生基因工程研究进展[J]. 分子植物育种,2015,13(1):228-234.

[3] 王紫萱,易自力. 卡那霉素在植物转基因中的应用及其抗性基因的生物安全性评价[J]. 中国生物工程杂志,2003, 23(6):9-13.

[4] Yao J L, Cohen D, Atkinson R, et al. Regeneration of transgenic plants from the commercial apple cultivar Royal Gala[J]. Plant Cell Reports, 1995, 14(7):407-412.

[5] 张春涛,朱洪德,殷奎德. 大豆子叶节对卡那霉素的敏感性研究[J]. 安徽农业科学,2012, 40(23):11584-11586.

[6] Liu J M, Yin Y T, Li H, et al. Effects of antibiotics on seed germination of different rape cultivars [J]. Agricultural Science & Technology, 2013, 14(5):707-709,721.

[7] 何云龙,段红英,段志强. 卡那霉素对拟南芥幼苗生长的影响[J]. 贵州农业科学,2010,38(3):12-14.

[8] Ivarson E, Ahlman A, Li X, et al. Development of an efficient regeneration and transformation method for the new potential oilseed cropLepidiumcampestre[J]. BMC Plant Biol, 2013,13:115.[9] Li M R, Li H Q, Wu G J. Study on factors influencing Agrobacterium-mediated transformation ofJatrophacurcas[J]. J Mol Cell Biol, 2006, 39(1): 83-89.

[10] 刘玉汇,张俊莲,王蒂,等. 不同烟草品种对卡那霉素抗性及耐盐性的差异[J]. 中国农学通报,2008,24(3):180-185.

[11] 张静妮,马晖玲,曹致中. 紫花苜蓿不同品种对卡那霉素敏感性分析[J]. 草原与草坪,2005(5):32-35.

[12] 张甲佳,张廷婷,徐娟,等. 不同花生品种对卡那霉素的敏感性研究[J]. 山东农业科学,2014,46(4):36-38.

[13] 马玲玲,魏延宏,朱华国,等. 棉花不同外植体对卡那霉素敏感性的研究[J]. 生物学杂志,2013,30(4):50-53.

[14] 肖娅萍,胡雅琴,王喆之. 卡那霉素对地灵愈伤组织诱导和生长的影响[J]. 西北植物学报,2003,23(2):318-322.

[15] 李俊兰,张寒霜,高鹏,等. 卡那霉素对棉花下胚轴愈伤组织生长的影响[J]. 棉花学报,1997,9(4):42-45.

[16] 郭秋云,王萍,刘兆普. 大豆下胚轴不定芽对卡那霉素和氯化钠耐性的研究[J].大豆科学,2013,32(2):211-215.

[17] 张月婷,桂大萍,黄家权,等. 花生胚小叶的离体再生及筛选压力选择[J]. 中国油料作物学报,2012,34(3):316-320.

[18] 方小平,许泽永,张宗义,等. 花生小叶外植体植株再生及农杆菌介导的基因遗传转化[J]. 中国油料,1996,18(4):52-56.

[19] 胡晓君,刘风珍,万勇善,等. 花生组织培养及苗期npt Ⅱ标记基因筛选剂适宜浓度的研究[J]. 山东农业大学学报:自然科学版,2007,38(1):28-34.

[20] 杨广东,朱祯,李燕娥,等. 几种抗生素对大白菜种子发芽及离体子叶再生的影响[J]. 华北农学报,2002,17(1): 55-59.

DOI:10.14001/j.issn.1002-4093.2016.02.004

收稿日期:2016-1-13

基金项目:国家花生产业技术体系(CARS-14);山东省农业科学院科技创新重点项目(2014CGPY09);青岛市民生计划(14-2-3-34-nsh)

作者简介:张青云(1989-),女,河北承德人,吉林农业大学硕士研究生,主要从事花生种用品质研究。

*通讯作者:王传堂(1968-),研究员,博士,主要从事高油酸花生育种研究。E-mail: chinapeanut@126.com

Abstract: As high in oil, common peanuts may quickly deteriorate and lose seed vigor under ambient conditions. That is the reason why only seeds harvested in previous season/year can be used as seeds in north China, and only the fall crops producd seeds can be chosen for next spring's crop in south regions of China. The present study revealed, for the first time, that high-oleic (HO) peanuts after an extended period of storage at ambient temperature (19 months), were still as good as those harvested from previous year in most of the seed quality characteristics. For each of the 3 HO peanut cultivars used, seeds of 2013 and 2014 did not differ significantly in standard seed germination on the 7th day and field emergence. Use of HO peanuts may therefore sustain the vigor of seed, in addition to health benefits for humans and longer shelf life of food products.

Key words: peanut; electric conductivity; field emergence; germination; high-oleic; seed vigor

摘要:普通花生含油量高,在自然温度下易快速劣变丧失种子活力。这是我国北方仅上年或上一季花生而我国南方仅秋花生来年可做种的原因。本研究首次证实,高油酸花生经过19个月自然条件下贮藏,在多数种用特性上不差于上年收获的花生。所有参试的3个高油酸品种,其2013年种子与2014年种子在第7天的发芽率和田间出苗率均无显著差异。由此证明,高油酸品种不仅有利于健康,能延长制品货架期,而且可保持种子活力。

关键词:花生;电导率;田间出苗率;萌发;高油酸;种子活力

1 Introduction

Undoubtedly, high oleate has become and will continue to be one of the most important breeding objectives of peanut. Earlier studies have showed that peanuts high in oleate are advantageous over their normal-oleic counterparts. Food products made from high-oleic (HO) peanuts have longer shelf life and are heart-healthier[1]. Research concerning seed storability of peanuts has been concentrated on normal-oleic (NO) genotypes. Perez and Arguello (1995) studied deterioration in peanut (ArachishypogaeaL. cv. Florman) seeds under natural and accelerated ageing, and concluded that while germination percentage was not a sensitive assay for detecting the degree of deterioration, changes in membrane integrity associated with seed deterioration occurred first in the embryonic axes, which could best be monitored by the conductivity seed vigor test[2]. Promchote et al. (2005) used hull-scrape method to divide NO peanut seeds into three different maturity groups to study the influence of maturity on seed storability[3]. They found that artificial and natural ageing of immature peanut seeds deteriorated faster than intermediate and mature seeds[3]. Using relative germination as an indicator for accelerated ageing tolerance (AAT), Shen et al. (2014) noted that AAT was correlated positively to oleate content, and negatively to linoleate in some treatments, without mentioning if HO peanut genoptypes were used in their study[4]. Up to now, no attempts have been made to ascertain if HO peanuts, after a longer duration of storage, is still usable as seeds without compromise in field emergence and productivity.

The aim of the present study is to make it clear if natural ageing affects seed germination and field emergence of HO peanut cultivars.

2 Materials and methods

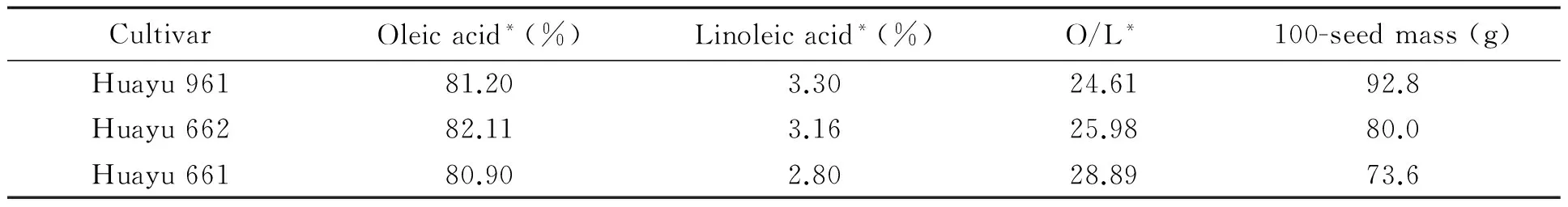

3 HO peanut cultivars bred by Shandong Peanut Research Institute (SPRI) were used in this study (Table 1). Among them, Huayu661 and Huayu662 are small-seeded varieties, and Huayu961 is a large-seeded cultivar.

Table 1 Some quality characteristics of the 3 HO peanut cultivars used in the study

Note: *Based on a report from Supervising and Testing Center for Oilseeds and Their Products (Wuhan), Ministry of Agriculture, China.

Peanut seeds used in the study were either from the 2014 crop or from the 2013 crop. Peanuts were sown in spring (early May), and harvested in fall (before mid-September). At the end of September of the same year, after sundried, pods or seeds (shells removed by hands) were stored at ambient temperature on the SPRI Experimental Farm in Laixi, Qingdao, China. All seeds used were sound mature kernels (SMKs).

In-house seed test began on May 8, 2015, when the seed dormancy of the entries vanished. For each entry, a total of 60 seeds were used for analysis (2 replications). For the samples stored as pods, shells were removed by hands just before initiation of the seed test. The roll towel method (between paper) as depicted by Upadhyaya and Gowda (2009)[5]and an incubation temperature of 28℃was used in the test. Only seeds with extruding hypocotyl and radicle no shorter than the length of the individual single seeds were counted as sprouts. Germination was recorded daily, and germination index (GI), vigor index (VI) and simplified vigor index (SVI)[6]were calculated using the following formulas:

GI= ∑(Gt/Dt)

Gt= No. of new sprouts counted on a specific day (Dt)

VI=GI×(Average radicle length in cm)

SVI=G3×(Length of radicle and hypocotyl in cm)

G3= No. of total sprouts by the 3rdday

Electric conductivity (EC) analysis was conducted according to the protocol described by Zhang et al. (2012)[7]with minor modifications.ECwas measured with a METTLER TOLEDO's FiveEasyTMConductivity Meter, model FE30 (Mettler-Toledo, LLC, Columbus, OH, USA). Two 30-seed subsamples were weighted to an accuracy of 0.01 g (W) and placed in 200 mL of de-ionized water in Erlenmeyer flasks, and the initial EC (d1) was measured. Flasks were covered to avoid loss of water and interference of dust and held at 20℃ for 24h, and conductivity (d2) was then measured. Absolute conductivity of seed leachate post boiling (d3) was also recorded. Electric conductivity of seed leachate (ECsl), reported as μS·cm-1·g-1, and relative electric conductivity (ECr) were calculated using the following formulas:

ECs l= (d2-d1)/W

ECr= (d2-d1)/(d3-d1)×100%

To test field performance, peanuts were sown with an expected population of 141176 hills per ha (one seed per hill) under polythene mulch

(Herbicide was sprayed prior to the placement of

the polythene film) on the same day with 1 replication in Experiment I (60 seeds/entry) and 4 replications in Experiment II and III (Totally 240 seeds/entry, randomized block design). Field emergence was counted 20 days after sowing.

Statistical analysis were performed with the DPS package (version 14.50)[8]. Data transformation was exploited where appropriate. Multiple comparison was conducted using Duncan's Multiple Range Test.

3 Results and analysis

3.1 In-house standard seed germination test

For seed germination (%) on the 3rdday (G3), significant difference was only detected in In-house Experiment II (x2=5.00234,df=1,p=0.02531<0.05), whereG3of Huayu662 seeds harvested in 2014 more than doubled that of naturally aged Huayu662 seeds of 2013 harvest (Table 2). Seed germination (%) on the 7thday (G7) ranged from 96.67%~100.00%, with no significant difference in all the 3 in-house experiments (Table 2). ForGI,VIandSVI, significant difference was solely reported from In-house Experiment II, where seeds of the 2013 crop had a much lessSVIthan the 2014 seeds (Table 2).

Table 2 Seed germination (%) on the 3rd(G3) and the 7thday (G7), germination Index (GI),

Note: *Figures marked with different letters were statistically differed at 0.05 probability level.

3.2 Electric conductivity analysis

Relative electric conductivity (ECr) of the entries within individual in-house experiment did not differ significantly (Table 2). Only electric conductivity of seed leachate (ECsl) from In-house Experiment III was statistically different (p= 0.0448<0.05) (Table 2). 2013 seeds of Huayu661 stored as seeds had anECslvalue significantly greater than that of 2013 seeds stored as pods or 2014 seeds of the same variety (Table 2).

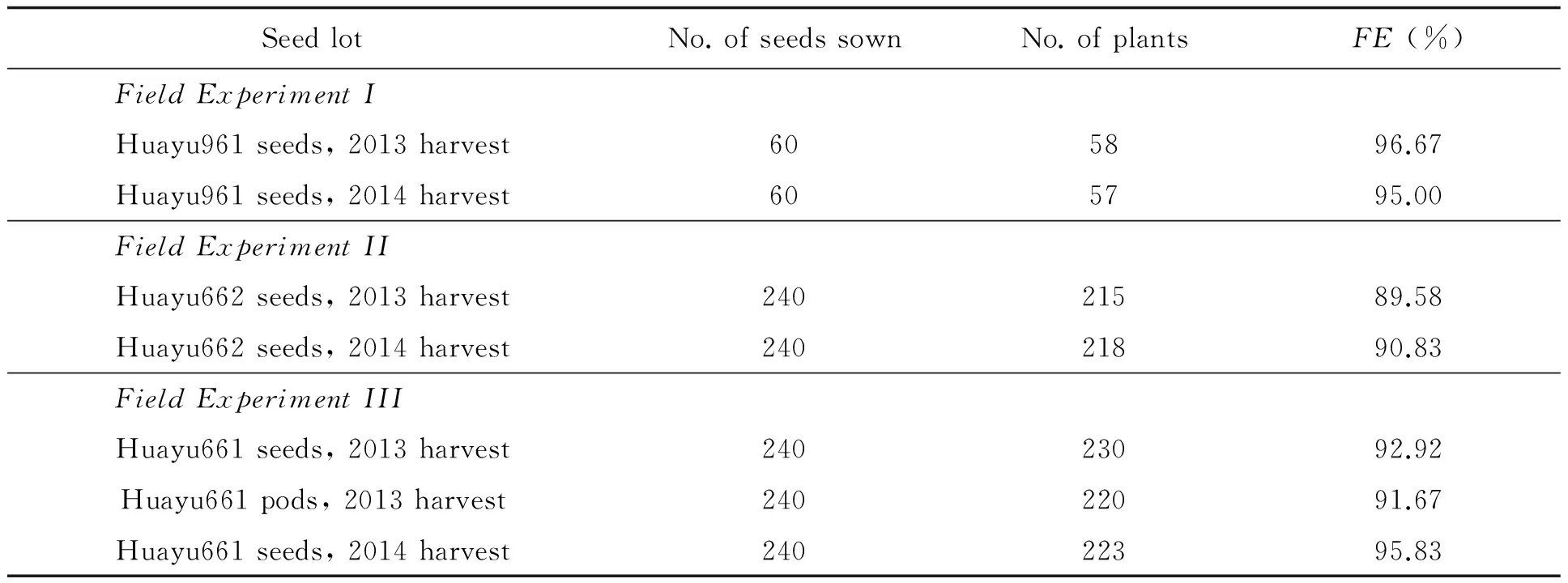

3.3 Field studies

Field emergence in the 3 experiments was listed in Table 3. No significant difference in field emergence in Field Experiment I was detected as analyzed withx2test (x2=0.00444,df=1,p=0.94687). No significant difference in field emergence in Field Experiment II and III was detected as analyzed with ANOVA (Using arsine square root data transformation and Duncan's Multiple Range Test) orx2test (In Field Experiment II,x2=0.01093,df=1,p=0.91674. In Field Experiment III,x2=0.12087,df=2,p=0.94135). Field survey showed that plants grown from different seed lots of each HO peanut cultivar developed equally well (Fig.).

Table 3 Field emergence (FE) of the entries

Fig. Plants grown from two seed lots of Huayu661 (75 days after sowing)Left row: 2014 seeds. Right row: 2013 pods.

3.4 Correlation analysis of seed quality characteristics

As shown in Table 4,G3was positively correlated withSVIandECr, whileG7was negatively related toECsl. A significant positive correlation also existed betweenGIandVIand betweenGIandSVI. Generally speaking, a HO peanut cultivar with a higherSVIorECralso has a greaterG3. Likewise, a lowECslmay be, however, an indicator of higherG7. We failed to establish a relationship between field emergence and any of the rest parameters. Please note that NO peanut seeds were not included in the present study. Inclusion of NO peanuts will possibly reveal relationships unidentified in the study.

Table 4 Pearson's correlation between seed quality characteristics of HO peanut cultivar

Note: Figures above the diagonal were probability levels, and figures below the diagonal were correlation coefficients. *Significant at 0.05 level. ** Significant at 0.01 level.

4 Conclusions and discussion

This communication reported, for the first time, the advantage of HO peanuts as seeds over common peanuts. On SPRI Experimental Farm (N36°48'40.44", E120°29'59.65"), the seeds from the 3 HO peanut cultivars, after an extended period of storage (19 months) under ambient conditions, viz., the seeds harvested in fall 2013, were still usable as seeds in spring 2015. For these seeds, according to the results from in-house seed test, only one of the 3 cultivars germinated slowly at early stage (Day 3), but at later stage (Day 7), germination percentage of the cultivar was roughly the same as that of seeds harvested in fall 2014. As expected, in field studies, for a specific HO peanut cultivar, the emergence ofoldandnewseeds lots was almost equivalent. It is interesting to find if theoldpeanuts may achieve yields as high as thenewones.

As reviewed by Sun et al. (2007)[9], lipid peroxidation, chromosome/gene aberrance, and embryo protein degradation are among the reasons causing seed vigor losses, seed ageing and deterioration. Peanut seeds contain about 50% oil and 26% protein. As such, ageing may adversely affect seed oil and protein. Sung and Jeng (1994) demonstrated that accelerated aging (AA) stimulated lipid peroxidation, and inhibited the activity of radical- and peroxide-scavenging enzymes[10]. Vasudevan et al. (2012) observed alteration in band number/intensity of protein/ peroxidase profiles in naturally and artificially aged peanut seeds[11]. As compared to linoleate, oleate is less prone to oxidization. NO peanuts generally have an oleate to linoleate ratio (O/L) of less than 2.5, with lower than 60% oleate, whereas linoleate may be as high as 50%. In contrast, HO peanuts have an O/L of no lower than 9[12], with more than 72% oleate, and linoleate may be as low as around 3%. The good storability of HO peanut seeds in the present study may be largely ascribed to their high oleate and low linoleate content. In addition, it is believed that other components, such as tocopherols and non-tocopherol antioxidants, may also have some roles[13]. But this has not been validated.

Anyway, the results from the present study is good news to peanut seed industry. In north regions in China (cooler areas), only peanuts harvested from the previous year/season can be used as seeds; NO peanuts harvested in the year before last year, when used as seeds, will encounter marked reduction in field emergence, incurring large yield losses. In south peanut production regions of China (warmer areas), peanuts may be sown in spring, fall, and even in winter. But, in general, merely the low-yielding fall peanuts can be used as seeds for next year's spring crop[14], in spite of their highly variable seed size, which is a stumbling block for mechanized sowing. Spring peanuts, though well developed and high yielding, subjected to high humidity coupled with high ambient temperature after harvest, will quickly lose their seed vigor under ordinary storage conditions, rendering them unusable as seeds for next year's crop. In China, HO peanuts provide a good opportunity to regulate seed supplies between years in north regions and may be of some help to find a solution to use spring peanuts as seeds for the subsequent year in south regions, with minimal storage measures taken. Similar needs also exist in other peanut producing countries worldwide. Hopefully, with the application of HO peanuts in seed industry, sufficient seed supply will result in reduced seed costs, eventually benefiting the whole peanut industry and consumers.

[1] Wang C T, Wang X Z, Tang Y Y, et al. Chapter 6. Genetic improvement in oleate content in peanuts [M]// Cook R W. Peanuts: Production, Nutritional Content and Health Implications. Nova Science Publisher, New York, 2014:95-140.

[2] Perez M A, Arguello J A. Deterioration in peanut (ArachishypogaeaL. cv. Florman) seeds under natural and accelerated aging[J]. Seed Science and Technology, 1995,23(2):439-445.

[3] Promchote P, Duanungpatra J, Chanprasert W. Influences of seed maturity and lipid composition on seed deterioration in large-seeded and medium-seeded peanut [C]// Summary International Peanut Conference 2005: Prospects and Emerging Opportunities for Peanut Quality and Utilization Technology. Kasetsart University, Bangkok, 2005:41.

[4] Shen Y, Liu Y H, Chen Z D. Identification and estimation of aging resistant varieties in peanut [J/OL]. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin, 2013, 29(18): 67-71.[2015-09-28]http://www.casb.org.cn/PublishRoot/casb/2013/18/2012-1775.pdf.

[5] Upadhyaya H D, Gowda C L L. Managing and Enhancing the Use of Germplasm-Strategies and Methodologies. Technical Manual No. 10 [M/OL]. International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, Patancheru, 2009:236. [2015-09-28] http://oar.icrisat.org/1316/1/40_2009_TME10_managing_and_enhancing.pdf.

[6] Chen R Z, Qiao Y Z, Fu J R. A study on the seed vigor of spring and fall peanuts [J/OL]. Seed. 1987 (2):43-46. [2015-09-28] http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-ZHZI198702012.htm.

[7] Zhang S Z, Xu P F, Wu J J. Experiments in Seed Physiology of Crops [M]. Beijing: Chemical Industry Press, 2012:39-45.

[8] Tang Q Y, Zhang C X. Data Processing System (DPS) software with experimental design, statistical analysis and data mining developed for use in entomological research [J/OL]. Insect Science. 2013, 20(2): 254-260. [2015-09-28] http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-7917.2012.01519.x/pdf.

[9] Sun Q, Wang J H, Sun B Q. Advances on seed vigor physiological and genetic mechanisms[J/OL]. Scientia Agricultura Sinica, 2007, 40(1):48-53. [2015-09-28] http://111.203.21.2:81/Jwk_zgnykx/CN/article/downloadArticleFile.do?attachType=PDF&id=9056.

[10] Sung J M, Jeng, T L. Lipid peroxidation and peroxide-scavenging enzymes associated with accelerated aging of peanut seed [J/OL]. Physiologia Plantarum, 1994, 91: 51-55. [2015-09-28]http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1994.tb00658.x/pdf.

[11] Vasudevan S N, Shakuntala N M, Doddagoudar S R, et al. Biochemical and molecular changes in aged peanut seeds [J]. The Ecoscan, 2012,1:347-352.

[12] Davis J P, Sweigart D S, Price K M, et al. Refractive index and density measurements of peanut oil for determining oleic and linoleic acid contents [J/OL]. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 2013, 90:199-206. [2015-09-28] http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11746-012-2153-4.

[13] Ahmed E M, Young C T. Composition, quality and flavor of peanuts[M]// Pattee H E, Young C T. Peanut Science and Technology. Yoakum: American Peanut Research and Education Society, 1982:655-688.

[14] Zhuang W J, Zhang S B, Wu Z H, et al. A comparative study on cytochemistry between spring and fall peanut seeds [J]. Acta Biologiae Experimentalis Sinica, 2001,34(4):299-305.

Study on Sensitivity of Peanut Leaflet to Kanamycin

WANG Feng-huan, HE Mei-jing, YANG Xin-lei, CUI Shun-li, MU Guo-jun, HOU Ming-yu, LIU Li-feng*

(NorthChinaLaboratoryofCropGermplasmResourcesofEducationMinistry/KeyLab.forCropGermplasmResourcesofHebei/CollegeofAgronomy,Agr.Univ.ofHebei,Baoding071001,China)

Kanamycin is a screening agent commonly used in plant genetic transformation. The study of susceptibility of peanut leaflet to kanamycin is important to the genetic transformation of peanut. 3 different genotypes of peanut (Fuluomansheng, Mayou1-1 and Puhua23) were used to study the impact of different concentration of kanamycinon on the development, differentiation and rooting of clustered shoots of peanut leaflet by calculating their yellowing rate, clustered shoots induction rate, rooting percentage and observing the growing status of explants, so as to confirm the suitable screening concentration. The results showed that different genotypes of peanut had different degrees of susceptibility to kanamycin. The suitable concentration of kanamycin for the differentiation of leaflet clustered shoots was 150 mg/L for Fuluomansheng, 100 mg/L for Mayou1-1 and 50 mg/L for Puhua 23; while for rooting of clustered shoots, the suitable concentration of kanamycin was 20 mg/L for Fuluomansheng, 20 mg/L for Mayou1-1 and 10 mg/L for Puhua 23. In this study, suitable screening concentration of kanamycin in stages of differentiation and rooting of clustered shoots was obtained, which laid foundation for the screening of positive plant in genetic transformation of peanut leaflet.

peanut (ArachishypogaeaL.); kanamycin; genotype; susceptibility

Effect of Natural Ageing on Seed Quality of High-Oleic Peanut

ZHANG Qing-yun1, WANG Chuan-tang1,2*, TANG Yue-yi2, WANG Xiu-zhen2, WU Qi2, SUN Quan-xi2, ZHANG Jian-cheng2, HU Dong-qing3, YU Shu-tao4, CHEN Ao5

(1.CollegeofAgronomy,JilinAgriculturalUniversity,Changchun130118,China; 2.ShandongPeanutResearchInstitute,Qingdao266100,China; 3.QingdaoEntry-ExitInspectionandQuarantineBureau,Qingdao266001,China; 4.LiaoningPeanutResearchInstitute,LiaoningAcademyofAgriculturalSciences,Fuxin123000,China; 5.InstituteofPeanut,ZhanjiangAcademyofAgriculturalSciences,Zhanjiang524094,China)

自然老化对高油酸花生种用品质的影响

张青云1,王传堂1,2*,唐月异2,王秀贞2,吴 琪2,孙全喜2,张建成2,胡东青3,于树涛4,陈 傲5

(1. 吉林农业大学农学院,吉林 长春 130118; 2. 山东省花生研究所,山东 青岛 266100; 3. 青岛出入境检验检疫局,山东 青岛 266001; 4. 辽宁省农业科学院花生研究所, 辽宁 阜新 123000; 5. 湛江市农业科学院花生研究所,广东 湛江 524094)

10.14001/j.issn.1002-4093.2016.02.003

2016-04-18

国家自然科学基金(31471523);农业部引进国际先进农业科学技术计划(“948”计划)(2013-Z65);高等学校博士学科点专项科研基金(2012130211002);河北省高等院校科学技术研究重点项目(ZH2011209)

王凤欢(1991-),女,河北沧县人,河北农业大学在读硕士,研究方向为细胞、分子遗传及其育种应用。

*通讯作者:刘立峰,教授,博士,主要从事花生基因组学与分子育种研究。E-mail:lifengliucau@126.com

S565.2;Q

A

565.2; S330.3+1 文献标识码:A