PYRAMID PAINS

2016-11-16BYROBERTFOYLEHUNWICK

BY ROBERT FOYLE HUNWICK

PYRAMID PAINS

BY ROBERT FOYLE HUNWICK

The weird and wild world of Chinese Ponzi schemes

成长中的金融业遭遇花样骗局

“ Many of my friends and their families had invested…I saw the company’s advertisements and awards on China’s state media and other channels, so I thought it was real.” The company was Ezubao—revealed this year to be a giant Ponzi, or pyramid scheme. The woman speaking to CNBC in February was “Jiang”, a middleaged investor who’d been scammed out of 150,000 RMB; she was too embarrassed to give her full name.

On paper, Ezubao seemed to be everything a liquid investor—someone looking for a place outside the heated Chinese property market to park their cash without losing out to inflation—could hope for.

Ezubao (sometimes known as Ezubo, due to its web address ezubo.com) was a peer-to-peer lending company that purported to match online lenders with borrowers, either individuals or businesses. Such schemes can be especially popular in China because, although the National Development and Reform Commission has promised to introduce one by 2017, there is currently no national credit-rating system and loans can often be hard to obtain through traditional banks.

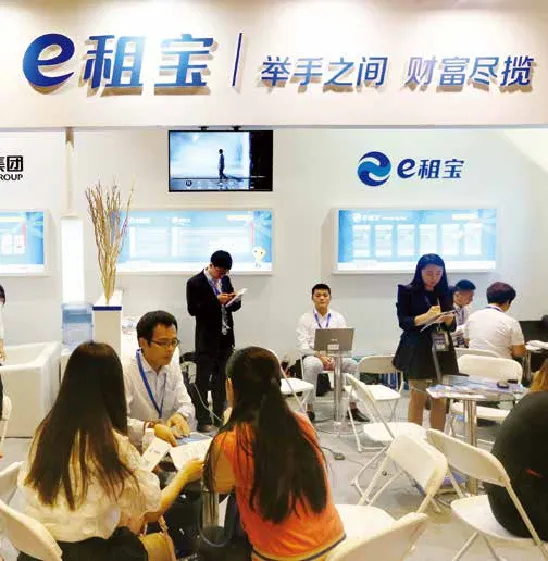

Ezubao's booth at the 2015 International Investment and Finance Exhibition of China in Beijing

“Interest is still negative, which means people are losing money by saving it in banks,” a financial product manager at Everbright Bank told China Youth Daily.“Stock and property became ordinary people’s only choice of investment. Now, the stock market is regressing, whereas property prices are at a terribly high level. The lack of investment vehicles is hugely limiting and putting a glass ceiling on people’s income. So it’s no wonder Ponzi schemes happen.”

Yet Ezubao’s credentials appeared impeccable. Investors told media that they’d seen the company advertised on China’s state broadcast network, CCTV,shortly before Xinwen Lianbo, the seven o’clock evening news. When a subsidiary of China’s official newswire Xinhua screened reports about the National People’s Congress, their broadcasts were sponsored by Ezubao;adverts for the firm even appeared on China’s high speed railway system and on the sides of government buildings. Others said they’d come across Ezubao while watching popular reality shows on regional satellite TV—these shows’ prominent celebrities meant many assumed that any advertising associated with their programming must be legitimate.

In fact, as anyone familiar with Jackie Chan’s mainland advertising career can attest, such thinking is almost always spuriously optimistic(Chan’s long list of disastrous endorsements include an auto-repair school that turned out to be a diploma mill, a carcinogenic shampoo purporting to prevent baldness, and an air-conditioning company whose units had a tendency to explode). And so it proved with Ezubao, whose fortunes spectacularly imploded in February when founder Ding Ning was arrested alongside 20 senior Ezubao employees—news reports quoted executive Zhang Min admitting that “95 percent” of its investment projects were fake, calling Ezubao “a downright Ponzi scheme” that may have bilked as many as 900,000 investors out of 53 billion RMB.

The staggering figures prompted immediate comparisons to Bernie Madoff, the New York fund manager whose Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities firm was exposed during the 2008 financial crisis as being another vast Ponzi, worth up to 50 billion USD. Ding, like Madoff, was made to endure a humiliating “perp walk” on national television, but state media interest in the Ezubao scam has not been particularly enduring (by contrast, two major American TV shows on the Madoff scandal, Madoff and The Wizard of Lies, were produced this year). And while US federal authorities have recovered more than 11 billion USD of Madoff’s stolen loot, thousands of Ezubao’s investors have been so far left penniless. Within days of one scandal, the Ministry of Public Security opened up an online platformfor investors of Ezubao to register and report their losses. Ping’an Beijing,the official Weibo account of Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau, which reported on March 23 that the ministry was “sparing no efforts” on the case, stating that investigators had “frozen, seized, and impounded a large sum of relative assets”. According to the report, 180,000 investors have registered.

PONZI SCHEMES, ALSO KNOWN AS PYRAMIDS, OPERATE ON THE NEED FOR CONSTANT EXPANSION

But hopes of seeing that money again are so far low. The investigation showed that a large amount of the capital absorbed by Ezubao was used to fund the lifestyles of the company management and their sprawling offices across 31 provinces, which alone consumed 800 million RMB per month just for staff salaries.

Founded in Anhui Province by Ding Ning in 2014, Ezubao was able to quickly position itself as the darling of Chinese investors by exploiting two key elements: trust and face. Speaking at Washington’s Brookings Institute in 2015, Peking University professor He Huaihong, author of Social Ethics in a Changing China: Moral Decay or Ethical Awakening? noted “a serious problem with morality in Chinese society now. The basic issues are that we lack basic trust.” The issue is one of deep concern to the government, added Brookings director Cheng Li, who said the matter was widely discussed: “lack of trust in present-day China [is]…certainly not politically taboo in the PRC,” said Cheng Li.

By managing to place advertising within the state-controlled infrastructure, Ezubao was able to persuade its clientele—from first-tier cities to rural areas—that the company was trustworthy. That isn’t because Chinese people necessarily trust their government any more than, say,Italians or Americans; rather, they trust leaders not to lose face by having a company associated with them publically fail. Many reasoned that a Solyndratype scandal would never be allowed in China.

Face also played a key element in Ezubao’s sales strategy: Ding encouraged staff to wear designer suits and display ostentatious jewelry. Meanwhile, top executives lived high on the hog, swapping outlandish gifts; a multi-million dollar property in Singapore was given by Ding to the company’s president, along with a pink diamond ring.

Ponzi schemes, also known as pyramids, operate on the need for constant expansion: money coming in from new investors is distributed to old ones under the guise of“returns”. In order to lure a steady stream of eager punters, such schemes usually offer returns that are higher than ordinary, blue-chip investments. In addition, critics say, stateowned banks tend to offer finance systems that are low-risk but user-unfriendly.

In March 2016, over 200 low-level sales agents caught up in pyramid schemes were reeducated and sent back to Anhui Province

Early adopters who receive these fraudulent dividends often unwittingly spread the wordto their friends—in a low-trust society, such relationship (guanxi) networks are seen as the closest thing to an unofficial regulator. Pyramid schemes finally collapse, as their Italian-American namesake Charles Ponzi’s did in 1920, when the flow of new money dries up. For Ezubao, this began to happen in late 2015; by December,the company had suspended its operations and panicked investors were protesting outside Ezubao’s headquarters; according to Xinhua,regulators are now working on a “warning system” to assess financial risks for wealthmanagement schemes.

BY DECEMBER, THE COMPANY HAD SUSPENDED ITS OPERATIONS AND PANICKED INVESTORS WERE PROTESTING OUTSIDE EZUBAO’S HEADQUARTERS

Ezubao is far from the first major Ponzi scheme in China. “Chuangxiao” or “pyramid sales”is a common crime—in Hefei alone, a 2013 crackdown netted 2,000 pyramid scammers—nor is it only investors who suffer. A Sichuanese former ayi told me she was once forced to pay a ransom, after her son was lured into becoming a sales agent in Chengdu and was then held hostage when he tried to leave the company. Despite their prevalence, such frauds are usually easy to spot, however, as they rely on the same familiar patterns: a tentpole-style figurehead to offer assurance, a reliance on friendship networks to recruit fresh income, and a business model whose absurdity only becomes truly apparent in the cold light of day.

Prior to Ezubao’s exposure, perhaps the bestknown example of the Ponzi in China was the Yilishen Tianxi Group, or “ant farm scam.”All the ingredients were baked in; based out of Liaoning, the scheme offered investors the opportunity to buy a box of ants for 10,000 RMB, which they were required to feed and water for 90 days; at no point, recipients were warned, should they ever open the box. At the end of this three-month period, a courier would arrive from Yilishen to collect the box, now allegedly filled with the life-giving corpses of thousands of valuable dead ants, an aphrodisiac,capable of curing practically anything according to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).

For nurturing this financially fabulous formicarium, investors could expect annual returns of up to 32 percent—though whether Yilishen actually began with a genuine TCM business model, or even if the boxes ever contained the precious ants, is not entirely clear. To boost sales, Yilishen hired the 57-year-old comedy sketch celebrity Zhao Benshan, who was more than happy to become the face of an erectile-dysfunction medication that’s banned by the Food and Drug Administration in America. The scam ran for eight years, during which a near-identical ant-farm scam in the same province collapsed, taking more than 10,000 investors for roughly 2.5 billion RMB.

Even more bizarrely, Wang was arrested,the initial charges were not for fraud but“inciting public unrest”. According to Xinhua,after a group of irate customers had turned up at Yilishen’s offices, Wang paid his own employees to organize a counter-protest against the local government. Street protests are a common response to fraud in China, as neither compensation schemes nor insurance policies are prevalent, and direct action is sometimes viewed as the best recourse for attracting official aid.

Not surprisingly, though, Wang’s ploy of attacking the Liaoning government did not go down well with local law enforcement—Wang was eventually tried in 2008 and sentenced to life imprisonment, reduced to19 years for good behavior last year. Zhao Benshan, meanwhile,weathered the storm and, despite an extended period of public disgrace in 2015, the Founding of a Party star recently released Spring Festival comedy The New Year’s Eve of Old Lee.

But not all Ponzi schemes rely on public hype to promote them; for some, a Madoff-esque aura of exclusivity is the allure. Take, for example,the group of dancing grannies who gathered outside the Beijing Wangfujing Catholic Church every weekday evening, practicing synchronized routines to the relentless beat of “Little Apple”. Few who witnessed this group of bobbing and spinning grannies (dama) would imagine that their leader, 56-year-old Zhang Yi, was running a 100 million RMB Ponzi, buoyed by the contributions of 40 of her faithful crew of sashaying seniors.

Some entrusted her with most of their life savings. “Dancing is a social-network platform,”sociologist Kuai Dasheng of the Shanghai Academy of Social Science recently told me. For this 100-million strong, elderly dama set, the habit has spread to “cultural exchanges, matchmakers,product promotion and even gangs.” Indeed,prior to her arrest in 2014, Zhang Yi behaved like the Empress Dowager herself, accepting lavish meals and expensive gifts from a circle of fawning acolytes, all eager to buy their way closer to a spot nearest the dancing queen.

Such cultish devotion can be a common element of small-scale pyramids that, unlike Ezubao or Yilishen, try to operate largely under the radar. One in Anhui, for example, included an initiation ceremony for those who invested their first 70,000 RMB, which included a dinner of fish, considered a traditional symbol of prosperity. According to a report by an undercover journalist with the Xinan Evening News, rituals among the group included a prohibition on slippers and an insistence that all male members must keep their shirt’s secondfrom-the-top button undone.

While, traditionally, Ponzi schemes have relied on word of mouth and aggressive sales agents to finance the model, experts fear that scams such as Ezubao may be the tip of the pyramid online.“A storm of credit risks is brewing in the peer-topeer lending industry,” Xu Zhipeng, president of ratings firm Dagong, warned in 2015.

“With no effective regulations and a low market-entry barrier, P2P finance is growing fast,” says Professor Yao Zheng of Zhejiang University’s School of Management. “They use fancy ‘Internet Plus’ concepts as a cover but lack risk controls…and are highly prone to default once masses of investors cash out.”Last year, the importance of web-based finance schemes was acknowledged by Beijing’s latest Five-Year Plan. But, according to Professor Yao, “The financial industry’s development still depends on the real economy—even though the internet has boosted the industry’s efficiency, it cannot change the supply-and-demand relationships of the market.”

Of the 3,600 P2P firms registered by the end of 2015, at least 1,000 are “problematic,”according to the China Banking Regulatory Commission. Why Ezubao was exposed while other pyramids continue to operate is an exercise in speculation. Considering its seemingly close relations with the state, some wonder if rival figures from one of China’s powerful state-owned banks helped engineer its demise. But one thing is inarguable: China’s economy is shifting seismically, as the government pivots from state-sponsored infrastructure and industry to promoting domestic consumption.

The changes, along with the accompanying slowdown after three decades of juggernaut growth, are likely to see hundreds, if not thousands more Ezubao-type frauds emerge from the murkier swamps of China’s shadowfinance sector.

Indeed, even as this article was being written, a fresh pyramid was revealed, further depressing the Chinese funding environment. In mid-April, Shanghai police announced that Zhongjin Capital Management had been placed under investigation, accused of “fraudulent fundraising” of over 30.3 billion RMB. A sprawling squid-like company, Zhongjin’s business group is believed to include over 100 separate companies and subsidiaries. Analysts have begun calling it “the new Ezubao”—just months after the original Ezubao, the term is already in danger of becoming a cliché.