植物群落构建机制研究进展

2016-10-24柴永福

柴永福, 岳 明

西北大学 西部资源生物与现代生物技术教育部重点实验室, 西安 710069

植物群落构建机制研究进展

柴永福, 岳明*

西北大学 西部资源生物与现代生物技术教育部重点实验室, 西安710069

群落构建研究对于解释物种共存和物种多样性的维持是至关重要的,因此一直是生态学研究的中心论题。尽管近年来关于生态位和中性理论的验证研究已经取得了显著的成果,但对于局域群落构建机制的认识仍存在很大争议。随着统计和理论上的进步使得用功能性状和群落谱系结构解释群落构建机制变为可能,主要是通过验证共存物种的性状和谱系距离分布模式来实现。然而,谱系和功能性状不能相互替代,多种生物和非生物因子同时控制着群落构建,基于中性理论的扩散限制、基于生态位的环境过滤和竞争排斥等多个过程可能同时影响着群落的构建。所以,综合考虑多种方法和影响因素探讨植物群落的构建机制,对于预测和解释植被对干扰的响应,理解生物多样性维持机制有重要意义。试图在简要回顾群落构建理论及研究方法发展的基础上,梳理其最新研究进展,并探讨整合功能性状及群落谱系结构的研究方法,解释群落构建和物种多样性维持机制的可能途径。在结合功能性状和谱系结构研究群落构建时,除了考虑空间尺度、环境因子、植被类型外,还应该关注时间尺度、选择性状的种类和数量、性状的种内变异、以及人为干扰等因素对群落构建的影响。

群落构建;功能性状;谱系结构;环境过滤;相似性限制

群落构建研究对于解释物种共存和物种多样性的维持是至关重要的,因此一直是生态学研究的中心论题,但同时也是充满争议的论题[1]。基于物种的生态位理论和中性理论是解释群落构建的两个主要理论,但是由于中性理论对传统生态位理论的严重挑战[2],导致了群落构建研究经历了反对、争辩和整合群落中性理论的蓬勃发展的十年。之后以Vellend[3]提出群落生态学的概念框架为标志性转折点,群落构建的研究进入了以中性群落构建为基点,探究群落构建中多种随机和生态位过程的新阶段[4]。近年来,大多数生态学家倾向于将中性理论和生态位理论的关键要素进行整合[5],并希望能构建同时包含随机性和确定性过程的综合模型。为此,在每个关键阶段国内群落构建研究领域的同仁也及时地介绍了当前研究的进展,例如周淑荣和张大勇[6]介绍了群落中性理论、牛克昌等[5]介绍了群落构建生态位理论和中性理论的争论和整合、朱璧如和张大勇[7]介绍了群落生态学的理论框架、牛红玉等[8]介绍了基于谱系分析的群落构建研究进展。这些综述为群落构建的研究提供了很好的研究思路。

近5年来由于一系列基于功能性状、谱系结构和尺度效应分析研究的快速发展,群落构建研究也取得了一些新的研究进展,例如区域和局域种库对群落构建的影响[9- 10]、气候和土壤等非生物环境筛的重要性[11- 12]、竞争导致的(性状/谱系结构/物种)趋同和趋异并存[13- 14]、生态位过程和随机作用重要性随尺度的改变[15]、适合度分化和平衡化作用的重要性[16- 17]、竞争能力的等级性和群落构建[18]、扩散作用和集合群落[15],等等。这也使得将生态位理论扩展到物种丰富度较高的生态系统中变为可能[19],同时为整合中性理论和生态位理论奠定了很好的基础。因此,综合考虑多种方法和影响因素探讨植物群落的构建机制,对于预测和解释植被对干扰的响应,理解生物多样性减少、气候变化、入侵物种对群落动态的影响有重要的科学意义[20]。

本文试图在简要回顾群落构建理论及研究方法发展的基础上,梳理其最新研究进展,并探讨整合功能性状及群落谱系结构的研究方法,解释群落构建和多样性维持的可能途径。

1 群落构建理论的主要内涵及发展

1.1生态位理论

1910年Johnson首次提出了生态位概念。Grinnell将其定义为群落中物种所占据的限制性环境因子单元。Gause[21]强调了群落中物种间的相互作用,提出了竞争排斥原理。基于生态位理论,Diamond[22]首次正式提出了群落构建规则,认为群落构建是大区域物种库中物种经过多层环境过滤和生物作用选入小局域的筛选过程。在生态位理论的验证中,人们研究了除生境中的可利用资源外,时间[23]、空间[24]、环境因子等其他因素对生态位分化及物种共存的影响[25-26]。随之,环境过滤和相似性限制两个相反的作用力被认为是局域植物群落组成的基本驱动力[27]。许多研究已经通过构建零模型(null model)等方法证明了环境过滤和相似性限制的存在[13,28-29]。

近年来学者们还根据不同的生态位模型对生态位理论进行了验证和补充。Adler等[30]、Tang和Zhou[31]分别构建群落动态模型,量化了生态位分化在大尺度及物种丰富度高的群落中对物种共存的重要性。Kylafis和Loreau[32]提出生态位构建的概念,认为基于生态位理论研究物种的共存,不仅应该考虑生态因子对物种的影响,还应该考虑物种对生态因子的影响。随后,Vannette 和Fukami[33]提出了生态位构建假说,认为如果将物种的生态位分为物种间的生态位重叠、对环境的影响生态位及对环境资源的需求生态位3个部分,基于生态位对群落构建的预测将更准确。Turnbull[34]等基于资源的生态位模型研究也表明,群落中物种间互补效应的出现是由于共存物种的生态位差异导致的,但是这种互补效应可能是短暂的,并不能保证物种稳定的共存。所以,群落的构建过程可能是在某一时间轴上的动态过程,不同的时期的构建过程可能不同。

1.2中性理论

中性理论是Hubbell[2]基于遗传学家Kimura的分子进化中性学说提出的。中性理论认为群落中相同营养等级的所有个体在生态位上等价,群落动态是随机的零和过程,并认为扩散限制对群落结构有着决定性的作用[2,35]。以往研究已经从物种等价性[36]、零和多项模型[37]和扩散限制[38]等角度对中性理论进行了验证和讨论。但是,有学者认为如果中性理论对个体对等性的假设成立,物种在生活史、竞争能力上的差异将不复存在,其它维持群落稳定的因素比如密度依赖也将被忽略[39]。

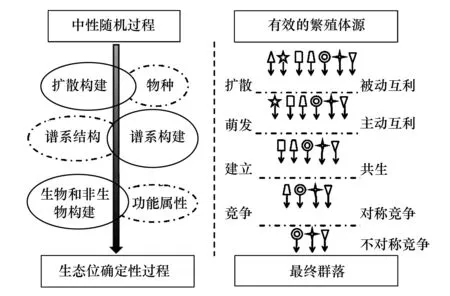

图1 中性随机和生态位过程在群落构建过程中的作用模式(图右仿自Stokes & Archer[56])Fig.1 Contributionspatterns of both neutral stochastic andniche processesin plants species assemblages during community development (right part simulated from Stokes & Archer[56])

近年来,人们在中性理论的验证中又考虑了空间尺度、环境因子、物种互利、密度依赖等因子对群落构建的影响。例如,Chase[40]证明了在生产力较高的环境中,随机的群落构建过程能维持更高的物种多样性。May 等[41]基于种-面积曲线的分析表明,在局域和集合群落尺度上扩散能力和物种多样性的关系会随着研究尺度的不同而改变。Xiao 等[42]指出促进作用对物种多样性有负影响,应作为中性理论的考虑因素。Gravel等[43]证明了中性理论在沼泽生态系统群落构建中的预测能力。同时,Rosindell[44]认为很多生态学家误解了中性理论,因为中性理论并不强调物种个体的生态位等价性,它只是想通过简单的假设使大家能更好的理解复杂的生态系统。总之,模式并不等于过程,已有的发现都是物种分布模式的描述,这并不能代表群落构建的过程,因为不同的过程可能导致相同的构建结果[44]。所以,应该尽可能的搜集更多类型的数据,特别是群落动态的数据来验证中性理论的实用性。

1.3生态位理论和中性理论的整合

如今,越来越多的生态学家认为群落构建的生态位理论与中性理论之争的最终归宿应该是二者的整合[45-47](图1)。因为,尽管中性理论对许多事实无法解释,但其合理的部分可以弥补生态位理论的关键缺陷[36,48-49]。比如,中性理论强调了群落构建中容易被忽略的过程,如扩散限制、迁入和迁出概率、生态漂变等[50],为在个体水平上探讨群落构建搭建了理论框架。Götzenberger等[4]对59篇植物群落构建研究论文的meta分析也表明,物种的非随机共存并不是普遍现象。这也间接证明了中性理论存在的合理性。

由于中性理论所表述的是在纯随机作用下的群落构建状态[51],所以在整合生态位理论和中性理论的过程中,一些研究者主张将中性理论作为群落构建的零模型[52-53,44]。Rosindell等认为中性模型可以用作零模型或近似值,但不能二者兼顾[44]。Tilman[54]和Gravel[55]分别提出了中性-生态位连续体假说和随机生态位假说。基于这些假说,Stokes和Archer[56]提出了新的群落构建过滤框架,此框架同时考虑了随机扩散和生态位分化,空间和时间尺度对群落构建的影响,并以热带草原的灌木群落为研究对象对其进行了验证。Weiher[57]等通过移栽实验证明了扩散、生态位分化和功能性状对群落功能构建有同等的重要性。Mutshinda和O′Hara[58]通过建模的方法将物种的多度变化分解为基于生态位和随机因子调控的两部分来整合中性理论和生态位理论,并用模拟数据做了验证。Smith 和Lundholm[59],Tuomisto等[60]和Diniz-Filho等[61]则认为用变异分解的方法区分中性和生态位过程对群落构建的影响并不可靠,因为这些结果很容易受到环境的空间自相关和取样差异的影响。尽管这些假说和整合后的理论框架还没有得到很统一的认识,在实际群落中也没有被充分验证,但是这些都为后期中性理论和生态位理论的整合奠定了很好的基础。

中性理论和生态位理论的整合已经成为一种必然趋势,生态位和中性理论争论的核心问题已经是生态位分化和随机作用在群落构建中的相对贡献大小的问题。今后需要用尽可能多的生态系统的数据来对已有的整合模型进行验证,以更好地理解确定性过程和随机过程在群落构建和生物多样性维持中的作用。

2 群落构建的研究方法及进展

2.1基于物种的方法

物种的有无和多度数据是群落生态学分析中最基本的数据,基于此数据矩阵,可以通过计算共存指数反映物种空间上的分离或聚集。但基于共存物种对数的均值计算的共存指数,并不能反映群落的实际情况,因为用不同的共存指数得出的结果可能不同。而且,物种分离既可能是由于竞争导致,也可能是由环境的变异造成的[4]。所以如果所研究的地点不能控制其环境异质性,用这些共存指数得出的结果可能无法解释。

物种多样性的提出使人们能够定量地描述群落的组成结构及其变化,其度量及分析方法已有大量研究,并不断用来验证中性理论中扩散限制对物种多样性的影响[62-63]。近年来,已有研究基于物种多样性从不同尺度、植被类型和海拔等方面探讨了群落构建机制过程中确定性因子和随机作用的相对重要性(表1)。Bruelheide 等[64]对中国古田山阔叶林的研究表明,物种的丰富度和组成受随机扩散作用影响,在群落演替的过程中每个物种都有相同的随机迁入率(表1)。Myers 等[65]将温带和热带森林的构建过程做了对比,发现热带森林构建过程支持扩散限制理论,而温带森林支持环境过滤理论。而Mori等[66]对日本北海道的温带森林的研究发现,高海拔群落构建是确定性过程,低海拔群落构建是随机过程。在尺度方面,Wang[67]对中国森林的研究表明,在区域尺度到局域尺度群落的构建中环境过滤和扩散限制比种间竞争的作用大。De Caceres等[68]关于全球森林的研究发现,全球尺度物种β多样性变化模式和γ多样性变化模式相同,主要是由于γ多样性的变化受局域尺度群落的随机构建过程影响。

2.2基于谱系结构的方法

群落内现有物种组成是进化过程和生态过程共同作用的结果, 分析物种间亲缘关系可以从进化角度深入地分析群落物种组成现状和原因[69]。以往,生态学家常用物种的多样性指数和种属比来反映群落中物种的丰富度及其亲缘关系[70]。但是,种属比并不能反应同属内物种间的亲缘关系,所以以此推断群落构建的成因不够准确。

Webb[71]首次试验性地将谱系树运用到群落生态学研究。随后, Webb等[27]又进一步系统地阐述了群落谱系结构研究的具体操作方法, 主要是通过比较群落内物种间的谱系距离与随机模型下的谱系距离是否有显著差异来揭示群落构建机制[8]。如果生境过滤作用占主导地位, 则相同生境将筛选出适应能力相似、亲缘关系偏近的物种,会表现为谱系的聚集;相反, 竞争排斥作用会使生态位相似的物种无法共存于同一环境, 则群落内物种亲缘关系较远,表现为谱系的发散。

Graham和Fine[72]将传统的β多样性和群落谱系学整合, 提出了谱系β多样性,从局域过程和区域过程两方面共同揭示现有生物多样性格局。González-Caro等[73]进一步提出了谱系α和β多样性,证明了南美西北部热带森林构建过程中环境梯度是谱系α和β多样性变化的主要驱动因子。近年来,基于谱系结构的研究多用来探讨环境过滤和竞争排斥在群落构建过程中的相对重要性(表1)。比如,Whitfeld等[74]对新几内亚热带森林的研究发现,热带森林演替过程中环境过滤是主要的群落构建驱动因子。在我国,Qian 等[75]和Huang[76]分别对中国长白山温带森林和南部亚热带森林的研究也表明,环境因子是木本群落物种谱系α和β多样性变化的主要驱动因素,而且在温带森林中环境因子对木本群落的影响要强于对草本群落的影响。

然而,用物种谱系距离代表特征距离是基于群落谱系结构推断构建过程的前提假设,此假设的合理性后来受到质疑。Webb等[27]提出生态性状的进化特征会影响群落的构建过程,同时认为功能性状按进化特征应该划分为与亲缘关系有关的保守性状和与亲缘关系无关的趋同性状。虽然很多研究表明,大多数生态性状是谱系保守的[77-78], 但是仍有一些生态性状被发现是进化易变的[79]。所以,谱系距离不能代表物种的特征距离,仅仅考虑谱系结构而忽略功能性状的群落分析结果对群落构建的解释是有限的[57]。

总之,直接用物种之间的亲缘关系距离分析群落多样性的维持机制时, 一定要注意其前提假设。在具体研究中, 可以适当选择一系列与研究目的相关的生态性状, 分析其进化特征后, 结合谱系研究结果, 共同揭示群落构建成因。

2.3基于功能性状的方法

植物功能性状是指那些能够影响植物个体适合度的形态、生理、物候等特征[80]。植物功能性状的差异不仅能够客观表达植物自身生理过程及对外部环境的适应策略的不同[81-82],而且也可以将群落结构与群落环境、生态系统过程等联系起来[83]。基于功能性状的群落构建主要被两个非随机的生态位过程所驱动:环境过滤和相似性限制。如果共存物种性状的分布模式相对于零模型表现为性状的聚集,那么环境过滤是群落构建的主要驱动者[84],即非生物的构建机制。相反,如果表现为性状的发散,那么相似性限制起主导作用。

许多研究已经基于功能性状证明了生境过滤和相似性限制的存在[28,85-86](表1)[19,28,64-68,73-76,85-89,91-120]。Ackerly 和Cornwell[84]为了区分群落性状沿着环境梯度和群落内部的变异大小,利用性状梯度分析(trait gradient analysis)方法将性状分为样地内α和样地间β两部分,证明了加利福尼亚森林构建过程中比叶面积、木质密度和植株最大高度对环境的响应更加明显。之后多项研究用性状梯度的方法验证了环境过滤在澳大利亚藤本和灌木[87]、退化草地[88-89]等群落构建中的作用。然而,Yan等[90]基于性状分别对生态位理论和中性理论做了验证,表明在亚高山的森林群落构建中相似性限制更能决定物种的共存。Dante等[28]基于花性状对弃耕地的群落构建过程的研究表明,样地间资源的变异对花性状的分布模式影响并不大,而生态位分化(相似性限制)可能是影响共存物种花性状变异的主要因子(表1)[19,28,64-68,73-76,85-89,91-120]。

但是还有一些研究认为,扩散限制可能是区域群落构成的主要调控因子[121]。支持扩散限制理论的研究多以种子性状的研究较多。Leishman[122]研究表明,种子的大小和数量的权衡决定了群落的结构。Dalling 和Hubbell[123]、Foster等[29]基于种子及繁殖性状分别对森林和草本群落演替过程的构建机制做了研究,表明种子大小的权衡会影响先锋群落的物种组成,而且扩散限制可能是维持区域物种多样性的主要因子。

在区域尺度上性状的聚集和发散在共存物种间也是可以同时存在的(表1)[19,28,64-68,73-76,85-89,91-120]。Grime[124]对草地群落构建的研究表明,和生产力相关的性状会表现出性状的聚集,和生理及繁殖相关的性状会表现出性状的发散。Cornwell 和Ackerly[125]对加利福尼亚森林群落的研究表明,生境过滤和相似性限制能同时影响群里的构建和性状的分布,而且二者的贡献值决定于所研究样地的非生物因子的变化。Naaf 和Wulf[96]对林下草本构建过程的研究也表明,随着土壤资源可利用性和光照强度的增加冠层高度的性状表现为性状聚集,而繁殖性状表现为性状的离散。因此,群落的构建过程可能不存在功能上的冗余,多个构建过程可以同时进行(表1)。

尽管如此,这些模式是受所选择分析的性状种类、数量、竞争能力等级和研究尺度影响的。原因有两点:(1)性状的聚集和发散有很强的尺度依赖性,同时也和群落内部物种竞争能力的等级有关。在相对同质的环境中,性状的聚集也可能是由对有低竞争力性状物种的排除造成的。(2)所选择性状的数量和性状的本征维度也可能影响着群落构建的结果。

表1 近4年植物群落构建主要研究概况[19,28,64-68,73-76,85-89,91-120]

2.4功能性状与谱系结构相结合

已有研究结果表明,基于中性理论的扩散限制、基于生态位的环境过滤和竞争排斥等多个过程可能同时影响着群落的构建。谱系和功能性状不能相互替代[126],在研究的过程中应该尽可能选择功能性状和谱系结构结合的方法来推断群落的构建过程[57]。Cadotte[119]将功能性状距离和谱系结构距离整合为功能—谱系距离(functional-phylogenetic distance),并在高山植被群落构建中证明了方法的可行性。

近年来已有学者开始用谱系和功能性状结合的方法来研究群落构建,主要包括不同尺度上、不同群落类型和演替过程中的群落构建(表1)[19,28,64-68,73-76,85-89,91-120]。例如,Baraloto[19]用谱系和功能性状相结合的方法研究了物种丰富度较高的法国新热带森林群落的构建机制,结果表明共存物种实际的功能性状和谱系结构距离比期望值要更加相似,证明环境过滤是该区群落构建的主导因子。而Swenson 等[113]对巴拿马和波多黎各两种不同演替阶段热带森林的研究表明,群落构建在谱系上是随机的,在功能性方面是非随机的。瑞典厄兰岛草原恢复演替过程中,早期表现为环境过滤,后期表现为竞争排斥[115],而亚得里亚海北部草原群落的构建过程中,谱系和功能性状都表现出了环境过滤和相似性限制的共同作用[117]。同样是热带森林,厄瓜多尔西部的森林在小尺度和中等尺度上环境因子和生态位分化(相似性限制)共同决定了物种的共存模式[127],但是中国西南部热带森林在空间尺度上群落的构建过程是确定性过程而非两个过程的共同作用[120]。温带森林的构建过程也受研究尺度的影响,大尺度上表现环境过滤和扩散限制,小尺度上表现竞争排斥[116]。同时,局域尺度上非生物过滤和扩散限制比群落的谱系结构对亚热带森林群落构建的影响更大[118]。

3 群落构建与研究尺度的关系

综合以上结果不难看出,在众多群落结构的研究中出现了各种结果,构建随机、性状或谱系的聚集或发散。这主要是由于群落构建的成因受多种因素的影响和控制,例如,尺度依赖性就是一个重要的影响因子。

基于植物功能性状的研究逐渐表明,性状的聚集和发散有很强的尺度依赖性。Zhang等[128]对中国东北温带森林的研究表明,在小尺度上物种的多度和尺度都要比期望值高,而大尺度上与期望值没有显著差异,这表明小尺度群落中物种间的竞争更强烈。Freschet等[95]对全球森林的研究也发现,从全球到区域群落构建性状的聚集程度是从区域到局域构建的两倍。所以,群落的构建机制可能有很多种,但是在小尺度上竞争可能是最重要的构建机制。Münkemüller 等[129]的研究还表明空间尺度(样方大小)、环境尺度(土壤类型)和生物尺度(生长型、植被层)的不同都会影响群落构建的过程,不同的生态系统对不同尺度变化的响应也不尽相同。

在谱系结构方面,群落的谱系结构和空间尺度也具有一定的相关性。已有研究表明,小尺度上亲缘关系较近的物种不易共存,会呈现出显著的谱系发散[130]。而随着群落空间尺度的增大, 谱系结构有从发散逐渐转为聚集[78],这种趋势在热带雨林的植物群落中更为明显[36]。Swenson 等[78]还发现,100m2可能是群落谱系变化的临界值,小于100m2群落谱系趋于发散,反之趋于聚集。国内学者黄建雄等[73]研究了古田山常绿阔叶林群落不同尺度下的谱系结构, 均发现大尺度上群落呈现显著的谱系聚集。不同尺度下群落生境、可利用资源及其它环境因子的变化可能是谱系结构随着空间尺度变化的主要原因[131]。群落的谱系结构也与分类群尺度和时间尺度有关。随着分类群尺度的降低, 谱系结构会越来越发散[132];随着物种生长时间的增加,植物的径级会逐渐增大,群落谱系结构也会趋于发散[78]。另外,演替也是群落构建的一个重要时间尺度,研究发现随着演替的进行, 谱系结构会更加趋于发散[133]。

所以, 群落构建的研究需要考虑多种尺度的影响, 不同空间、时间、分类群尺度下的群落构建成因不同。

4 其他因素对群落构建的影响

(1)环境因子前已述及,环境因素对群落内物种组成有着非常重要的作用,不同的生境可形成不同的构建机制。Myers 等[65]比较了温带和热带森林的群落构建机制,结果表明在热带森林群落构建过程中扩散限制占优势,而在温带森林的群落构建过程中环境过滤占优势。而且,同样是热带森林,雨林和干旱森林在演替过程中的群落构建机制变化是完全不一样的[110]。因为在雨林中光是群落演替的主要驱动因子,而在干旱森林中水分是主要驱动因子。另外海拔的不同也会影响群落的构建机制,Kembel和Hubbell[134]研究发现巴拿马大样地内高海拔生境下的植物群落表现为谱系聚集,低海拔沼泽和斜坡生境的群落则为谱系发散。总之, 不同的生境可能形成不同的构建机制, 但是目前并没有统一的规律来说明一种生境一定会对应一种特定的构建机制。这是因为一个群落的物种组成不仅受环境条件、生物间相互作用等局域因素的影响, 还受到地史过程、物种形成等区域过程的影响[121]。

(2)种内变异基于功能性状的研究方法越来越多地被用于群落构建的研究,但多数研究都以平均性状来描述物种特征,而忽略种内变异。已有证据表明,种内变异和遗传多样性一样,能显著的影响群落的构建和稳定性[135-137]。Jung[138]的研究表明,在整个群落构建过程中种内变异占群落水平上物种性状变异的44%,并认为种内变异会通过减轻物种被生物和非生物因子的过滤促进物种的共存。Albert 等[139]认为种内性状变异能否忽略(用均值代替)取决于所研究的生态系统、选择的性状、物种和研究目的决定的。Xiao等[42,140]发现无论在基于生态位构建的群落中还是随机构建的群落中,促进作用都有助于物种的共存和群落生物多样性的维持,而促进作用很大程度来源于种内的变异。所以,在基于性状的群落生态学研究中种内性状应该作为一个影响因子被考虑。

(3)性状的本征维度性状的数量和种类的选择对研究结果有很大的影响,如何才能选择合适的种类和数量来反映群落构建的真实过程。在众多已测的功能性状中,很多性状是共变的,比如在全球叶片经济型谱中提到的6大叶性状[141]。这些性状都具有强烈的正或负相关,在分析中完全可以用一个性状轴来代替。植物性状的本征维度是能描述植物功能性状变异的最少性状轴[142]。明确植物性状的本征维度不仅能够降低研究性状的数量,更能准确的预测植物对环境的响应,理解群落的构建机制[143]。Laughlin[142]认为植物性状的本征维度不会超过6,这就表明植物性状的维度是有可控的上限的。为了准确有效的理解基于性状的群落构建过程,应该最小化性状的数量,最大化维度的数量。植物的不同器官承载着植物不同的功能,每个器官都包含植物对环境响应的潜在信息。叶片是最明显也是人们最关注的器官,它表明了植物沿着环境梯度在叶寿命和最大光合能力上的权衡[141]。种子的扩散能力是物种扩散和繁殖的保障,种子大小和种子重量的权衡是植物适应环境的基本策略,而且种子的大小和形状的权衡是植物繁殖策略的象征[144]。茎杆密度是植物水分利用效率和抗旱、抗冻能力的权衡,同时也是生长速率和存活率的权衡[145]。植物的根性状,比如比根长、根密度也是植物的重要性状,反映了植物生长速率、生活史及增殖扩散能力[146]。花的物候学性状也是植物的关键功能,开花时间以及花期受环境和发育调控,反映了共存物种的相互作用[147]。LHS(leaf-height-seed)植物策略表提出比叶面积、植株高度和种子重量3个性状影响着植物的散布、生长和抗性[148], 分别代表了独立的多元性状轴。Westoby和他的团队随后又增加了叶面积、木质密度和根的性状[149]作为重要的植物策略维度。所以,在研究的过程中应该尽可能的选择植物不同器官的性状,特别是根、茎、叶、花的性状。

5 研究展望

群落构建机制的研究是一个长期而艰巨的课题,中性理论和生态位理论之争的最终归宿将是二者的整合。虽然零模型和中性-生态位连续体假说及随机生态位假说的提出为这种耦合提供了很好的开端,但是由于研究尺度、环境因子、性状选择及其它影响因子的不确定,以至于所得结果仍然没有一定的规律性[4]。综合这些生态因子,结合性状和群落谱系结构的研究方法是阐明生态位分化的确定性过程和中性作用的随机过程如何耦合,共同形成和维持物种多样性的必经之路。综合已有的研究成果,可以认为:

(1)同时考虑空间和时间尺度下植物群落的构建过程对完整地理解构建机制很有必要。植物群落构建是一个带有时间轴的动态过程,在物种逐渐替代、更新的过程中,不同时期可能有不同的构建机制,因此仅仅通过现有现象得出的结果难免会忽略构建机制的演变过程。比如在演替的早期,由于先锋物种都处在高光的环境中,土壤营养的可利用性是确定群落物种组成的环境筛,随着演替的进行,物种多样性的增加,物种间的相互作用可能会逐渐优于环境因子成为群落结构的决定因子。然而,不同生态系统在时间梯度上的群落构建过程也不同,比如干旱森林和雨林在次生演替过程就表型出完全不同的构建机制[110,102]。

(2)在选择性状时,应该增加性状的维度,减少性状的数量,所选的性状应该尽可涉及植物的多个器官。近年来,人们一直在通过测定物种的生理生态、形态学和生活策略等功能性状理解群落构建。已有研究也已经测量了植物的很多性状,但是很多性状只反映了植物的同一种功能策略。植物的不同器官承载着植物不同的功能,每个器官都包含植物对环境响应的独立的潜在信息。所以,多种器官的选择方式可以作为增加维度的参考。

(3)进一步理解基于功能性状物种的共存机制。虽然基于性状对群落构建的研究有很大的进展,但是最终还没能提出一个完善的机制来预测全球和地方气候变化对物种多样性的影响。现在基于性状的方法主要是通过分析性状的分布模式来确定环境过滤和生态位分化二者的重要性。虽然性状的分布能解释物种多样性的维持,但是没有任何的预测能力。比如要基于性状预测氮沉降对物种多样性的影响,就要知道所研究群落的共存机制。如果资源共享是群落的共存机制,那么氮沉降就会影响群落中物种的多样性,如果土壤的温度的变化是物种共存的原因,那么氮沉降就不会影响物种的多样性[150]。所以,要达到群落生态学的最终目的,需要从关注性状的现象学研究转为基于性状对共存机制的验证研究[151]。

(4)综合考虑环境变量、人为干扰等其他生态过程深入探讨群落构建成因。不同的生态系统中群落构建的驱动因子不同,对于干旱森林而言,水分是群落构建的主要驱动因子,而对于热带雨林,光是群落结构组成的主要决定性因子[102]。同时,人为的干扰也会改变群落的构建过程。比如Bhaskar[110]的研究表明,人为造成的次生演替林和原始老林会表现出不同的构建机制。所以,结合不同生态系统的环境因子、人为干扰等其他生态过程对准确理解群落构建的具体过程有重要作用。

(5)将种内变异作为群落构建过程的影响因子。基于功能性状探讨群落构建的机制已有了很大的进展,但是多数研究中的物种性状都是用性状平均值来代替,这样就忽视了种内变异对群落构建的影响。但是,近几年的很多研究已经表明种内变异对群落的动态和生态系统的功能有显著的影响[152,135]。所以,在以后的研究中应该重视种内变异对群落构建的影响。

[1]Rosindell J, Hubbell S P, Etienne R S.Theunifiedneutraltheoryofbiodiversityandbiogeographyat age ten. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2011, 26(7): 340- 348.

[ 2]Hubbell S P. The Unified Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

[ 3]Vellend M. Conceptual synthesis in community ecology. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 2010, 85(2): 183- 206.

[ 4]Götzenberger L, de Bello F, Bråthen K A, Davison J, Dubuis A, Guisan A, Lepš J, Lindborg R, Moora M, Pärtel M, Pellissier L, Pottier J, Vittoz P, Zobel K, Zobel M. Ecological assembly rules in plant communities-approaches, patterns and prospects. Biological Reviews, 2012, 87(1): 111- 127.

[ 5]牛克昌, 刘怿宁, 沈泽昊, 何芳良, 方精云. 群落构建的中性理论和生态位理论. 生物多样性, 2009, 17(6): 579- 593.

[ 6]周淑荣, 张大勇. 群落生态学的中性理论. 植物生态学报, 2006, 30(5): 868- 877.

[ 7]朱璧如, 张大勇. 基于过程的群落生态学理论框架. 生物多样性, 2011, 19(4): 389- 399.

[ 8]牛红玉, 王峥峰, 练琚愉, 叶万辉, 沈浩. 群落构建研究的新进展: 进化和生态相结合的群落谱系结构研究. 生物多样性, 2011, 19(3): 275- 283.

[ 9]de Bello F, Price J N, Münkemüller T, Liira J, Zobel M, Thuiller W, Gerhold P, Götzenberger L, Lavergne S, Lepš J, Zobel K, Pärtel M. Functional species pool framework to test for biotic effects on community assembly. Ecology, 2012, 93(10): 2263- 2273.

[10]Lessard J -P, Belmaker J, Myers J A, Chase J M, Rahbek C. Inferring local ecological processes amid species pool influences. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2012, 27(11): 600- 607.

[11]Kraft N J B, Adler P B, Godoy O, James E C, Fuller S, Levine J M. Community assembly, coexistence and the environmental filtering metaphor. Functional Ecology, 2015, 29(5): 592- 599.

[12]Laliberté E, Zemunik G, Turner B L. Environmental filtering explains variation in plant diversity along resource gradients. Science, 2014, 345(6204): 1602- 1605.

[13]Mayfield M M, Levine J M. Opposing effects of competitive exclusion on the phylogenetic structure of communities. Ecology Letters, 2010, 13(9): 1085- 1093.

[14]Godoy O, Kraft N J B, Levine J M. Phylogenetic relatedness and the determinants of competitive outcomes. Ecology Letters, 2014, 17(7): 836- 844.

[15]Chase J M, Myers J A. Disentangling the importance of ecological niches from stochastic processes across scales. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 2011, 366(1576): 2351- 2363.

[16]HilleRisLambers J, Adler P B, Harpole W S, Levine J M, Mayfield M M. Rethinking community assembly through the lens of coexistence theory. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 2012, 43: 227- 248.

[17]Cardinale B J. Towards a general theory of biodiversity for the Anthropocene. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 2013, doi:10.12952/journal.elementa.000014.

[18]Kunstler G, Lavergne S, Courbaud B, Thuiller W, Vieilledent G, Zimmermann N E, Kattge J, Coomes D A. Competitive interactions between forest trees are driven by species′ trait hierarchy, not phylogenetic or functional similarity: implications for forest community assembly. Ecology Letters, 2012, 15(8): 831- 840.

[19]Baraloto C, Hardy O J, Paine C E T, Dexter K G, Cruaud C, Dunning L T, Gonzalez M-A, Molino J -F, Sabatier D, Savolainen V, Chave J. Using functional traits and phylogenetic trees to examine the assembly of tropical tree communities. Journal of Ecology, 2012, 100(3): 690- 701.

[20]Prach K, Walker L R. Four opportunities for studies of ecological succession. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2011, 26(3): 119- 123.

[21]Gause G F. The Struggle for Existence. Baltimore:Williams and Wilkins, 1934.

[22]Diamond J M. Assembly of species communities //Cody ML, Diamond JM, eds. Ecology and Evolution of Communities. Cambridge, Massachusetts:Belknap Press of Harvard University, 1975:342- 444.

[23]Chesson P. Mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 2000, 31: 343- 366.

[24]Murrell D J, Law R. Heteromyopia and the spatial coexistence of similar competitors. Ecology Letters, 2003, 6(1): 48- 59.

[25]Chase J M. Community assembly: when should history matter?. Oecologia, 2003, 136(4): 489- 498.

[26]Chase J M, Leibold M A. Ecological Niches: Linking Classical and Contemporary Approaches. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

[27]Webb C O, Ackerly D D, McPeek M A, Donoghue M J. Phylogenies and community ecology. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 2002, 33: 475- 505.

[28]Dante S K, Schamp B S, Aarssen L W. Evidence of deterministic assembly according to flowering time in an old-field plant community. Functional Ecology, 2013, 27(2): 555- 564.

[29]Foster B L, Dickson T L, Murphy C A, KarelI S, Smith V H. Propagule pools mediate community assembly and diversity‐ecosystem regulation along a grassland productivity gradient. Journal of Ecology, 2004, 92(3): 435- 449.

[30]Adler P B, Ellner S P, Levine J M. Coexistence of perennial plants: an embarrassment of niches. Ecology Letters, 2010, 13(8): 1019- 1029.

[31]Tang J F, Zhou S R. The importance of niche differentiation for coexistence on large scales. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 2011, 273(1): 32- 36.

[32]Kylafis G, Loreau M. Niche construction in the light of niche theory. Ecology Letters, 2011, 14(2): 82- 90.

[33]Vannette R L, Fukami T. Historical contingency in species interactions: towards niche-based predictions. Ecology Letters, 2014, 17(1): 115- 124.

[34]Turnbull L A, Levine J M, Loreau M, Hector A. Coexistence, niches and biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning. Ecology Letters, 2013, 16(S1): 116- 127.

[35]Bell G. The distribution of abundance in neutral communities. The American Naturalist, 2000, 155(5): 606- 617.

[36]Hubbell S P. Neutral theory and the evolution of ecological equivalence. Ecology, 2006, 87(6): 1387- 1398.

[37]Houlahan J E, Currie D J, Cottenie K, Cumming G S, Ernest S K M, Findlay C S, Fuhlendorf S D, Gaedke U, Legendre P, Magnuson J J, McArdle B H, Muldavin E H, Noble D, Russell R, Stevens R D, Willis T J, Woiwod I P, Wondzell S M. Compensatory dynamics are rare in natural ecological communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2007, 104(9): 3273- 3277.

[38]Legendre P, Mi X C, Ren H B, Ma K P, Yu M J, Sun Y -F, He F L. Partitioning beta diversity in a subtropical broad-leaved forest of China. Ecology, 2009, 90(3): 663- 674.

[39]Yu D W, Terborgh J W, Potts M D. Can high tree species richness be explained by Hubbell′s null model?. Ecology Letters, 1998, 1(3): 193- 199.

[40]Chase J M. Stochastic community assembly causes higher biodiversity in more productive environments. Science, 2010, 328(5984): 1388- 1391.

[41]May F, Giladi I, Ziv Y, Jeltsch F. Dispersal and diversity-unifying scale-dependent relationships within the neutral theory. Oikos, 2012, 121(6): 942- 951.

[42]Xiao S, Zhao L, Zhang J L, Wang X T, Chen S Y. The integration of facilitation into the neutral theory of community assembly. Ecological Modelling, 2013, 251: 127- 134.

[43]Gravel D, Poisot T, Desjardins-Proulx P. Using neutral theory to reveal the contribution of meta-community processes to assembly in complex landscapes. Journal of Limnology, 2014, 73(S1): 61- 73.

[44]Rosindell J, Hubbell S P, He F L, Harmon L J, Etienne R S. The case for ecological neutral theory. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2012, 27(4): 203- 208.

[45]Alonso D, Etienne R S, McKane A J. The merits of neutral theory. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 2006, 21(8): 451- 457.

[46]Adler PB, HilleRisLambers J, Levine J M. A niche for neutrality. Ecology Letters, 2007, 10(2): 95- 104.

[47]Wennekes P L, Rosindell J, Etienne R S. The neutral-niche debate: a philosophical perspective. ActaBiotheoretica, 2012, 60(3): 257- 271.

[48]Zhou S R, Zhang D Y. A nearly neutral model of biodiversity. Ecology, 2008, 89(1): 248- 258.

[49]Lin K, Zhang D Y, He F L. Demographic trade-offs in a neutral model explain death-rate-abundance-rank relationship. Ecology, 2009, 90(1): 31- 38.

[50]Etienne R S, Alonso D. A dispersal-limited sampling theory for species and alleles. Ecology Letters, 2005, 8(11): 1147- 1156.

[51]Harte J. The value of null theories in ecology. Ecology, 2004, 85(7): 1792- 1794.

[52]Gaston K J, Chown S L. Neutrality and the niche. Functional Ecology, 2005, 19(1): 1- 6.

[53]Gotelli N J, McGill B J. Null versus neutral models: what′s the difference?. Ecography, 2006, 29(5): 793- 800.

[54]Tilman D. Niche tradeoffs, neutrality, and community structure: a stochastic theory of resource competition, invasion, and community assembly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2004, 101(30): 10854- 10861.

[55]Gravel D, Canham C D, Beaudet M, Messier C. Reconciling niche and neutrality: the continuum hypothesis. Ecology Letters, 2006, 9(4): 399- 409.

[56]Stokes C J, Archer S R. Niche differentiation and neutral theory: an integrated perspective on shrub assemblages in a parkland savanna. Ecology, 2010, 91(4): 1152- 1162.

[57]Weiher E, Freund D, Bunton T, Stefanski A, Lee T, Bentivenga S. Advances, challenges and a developing synthesis of ecological community assembly theory. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2011, 366(1576): 2403- 2413.

[58]Mutshinda C M, O′Hara R B. Integrating the niche and neutral perspectives on community structure and dynamics. Oecologia, 2011, 166(1): 241- 251.

[59]Smith T W, Lundholm J T. Variation partitioning as a tool to distinguish between niche and neutral processes. Ecography, 2010, 33(4): 648- 655.

[60]Tuomisto H, Ruokolainen L, Ruokolainen K. Modelling niche and neutral dynamics: on the ecological interpretation of variation partitioning results. Ecography, 2012, 35(11): 961- 971.

[61]Diniz-Filho J A F, Siqueira T, Padial A A, Rangel T F, Landeiro V L, Bini L M. Spatial autocorrelation analysis allows disentangling the balance between neutral and niche processes in metacommunities. Oikos, 2012, 121(2): 201- 210.

[62]马克平, 刘玉明. 生物群落多样性的测度方法Ⅰα多样性的测度方法(下). 生物多样性, 1994, 2(4): 231- 239.

[63]陈圣宾,欧阳志云, 徐卫华, 肖燚. Beta多样性研究进展.生物多样性, 2010, 18(4): 323- 335.

[64]Bruelheide H, Böhnke M, Both S, Fang T, Assmann T, Baruffol M, Bauhus J, Buscot F, Chen X Y, Ding B Y, Durka W, Erfmeier A, Fischer M, Geiβler C, Guo D L, Guo L D, Härdtle W, He J S, Hector A, Kröber W, Kühn P, Lang A C, Nadrowski K, Pei K Q, Scherer-Lorenzen M, Shi X Z, Scholten T, Schuldt A, Trogisch S, von Oheimb G, Welk E, Wirth C, Wu Y T, Yang X F, Zeng X Q, Zhang S R, Zhou H Z, Ma K P, Schmid B. Community assembly during secondary forest succession in a Chinese subtropical forest. Ecological Monographs, 2011, 81(1): 25- 41.

[65]Myers J A, Chase J M, Jiménez I, Jørgensen P M, Araujo-Murakami A, Paniagua-Zambrana N, Seidel R. Beta-diversity in temperate and tropical forests reflects dissimilar mechanisms of community assembly. Ecology Letters, 2013, 16(2): 151- 157.

[66]Mori A S, Shiono T, Koide D, Kitagawa R, Ota AT, Mizumachi E. Community assembly processes shape an altitudinal gradient of forest biodiversity. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2013, 22(7): 878- 888.

[67]Wang S P, Tang Z Y, Qiao X J, Shen Z H, Wang X P, Zheng C Y, Fang J Y. The influence of species pools and local processes on the community structure: a test case with woody plant communities in China′s mountains. Ecography, 2012, 35(12): 1168- 1175.

[68]De Cáceres M, Legendre P, Valencia R, Cao M, Chang L W, Chuyong G, Condit R, Hao Z Q, Hsieh C -F, Hubbell S, Kenfack D, Ma K P, Mi X C, Noor M N S, Kassim A R, Ren H B, Su S -H, Sun I -F, Thomas D, Ye W H, He F L. The variation of tree beta diversity across a global network of forest plots. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2012, 21(12): 1191- 1202.

[69]黄建雄, 郑凤英, 米湘成. 不同尺度上环境因子对常绿阔叶林群落的谱系结构的影响. 植物生态学报, 2010, 34(3): 309- 315.

[70]Simberloff D S. Taxonomic diversity of island biotas. Evolution, 1970, 24(1): 23- 47.

[71]Webb C O. Exploring the phylogenetic structure of ecological communities: an example for rain forest trees. The American Naturalist, 2000, 156(2): 145- 155.

[72]Graham C H, Fine P V A. Phylogenetic beta diversity: linking ecological and evolutionary processes across space in time. Ecology Letters, 2008, 11(12): 1265- 1277.

[73]González-Caro S, Umaa M N,lvarez E, Stevenson P R, Swenson N G. Phylogenetic alpha and beta diversity in tropical tree assemblages along regional-scale environmental gradients in northwest South America. Journal of Plant Ecology, 2014, 7(2): 145- 153.

[74]Whitfeld T J S, Kress W J, Erickson D L, Weiblen G D. Change in community phylogenetic structure during tropical forest succession: evidence from New Guinea. Ecography, 2012, 35(9): 821- 830.

[75]Qian H, Hao Z Q, Zhang J. Phylogenetic structure and phylogenetic diversity of angiosperm assemblages in forests along an elevational gradient in Changbaishan, China. Journal of Plant Ecology, 2014, 7(2): 154- 165.

[76]Huang J X, Zhang J, Shen Y, Lian J Y, Cao H L, Ye W H, Wu L F, Bin Y. Different relationships between temporal phylogenetic turnover and phylogenetic similarity and in two forests were detected by a new null model. PLoS One, 2014, 9(4): e95703.

[77]Chazdon R L, Careaga S, Webb C, Vargas O. Community and phylogenetic structure of reproductive traits of woody species in wet tropical forests. Ecological Monographs, 2003, 73(3): 331- 348.

[78]Swenson N G, Enquist B J, Thompson J, Zimmerman J K. The influence of spatial and size scale on phylogenetic relatedness in tropical forest communities. Ecology, 2007, 88(7): 1770- 1780.

[79]Fine P V A, Miller Z J, Mesones I, Irazuzta S, Appel H M, Stevens M H H, Sääaksjärvi I, Schultz J C, Coley P D. The growth-defense trade-off and habitat specialization by plants in Amazonian forests. Ecology, 2006, 87(S7): S150-S162.

[80]Violle C, Navas M -L, Vile D, Kazakou E, Fortunel C, Hummel I, Garnier E. Let the concept of trait be functional!. Oikos, 2007, 116(5): 882- 892.

[81]孟婷婷, 倪健, 王国宏. 植物功能性状与环境和生态系统功能. 植物生态学报, 2007, 31(1): 150- 165.

[82]周道玮. 植物功能生态学研究进展. 生态学报, 2009, 29(10): 5644- 5655.

[83]Laughlin D C. Nitrification is linked to dominant leaf traits rather than functional diversity. Journal of Ecology, 2011, 99(5): 1091- 1099.

[84]Ackerly D D, Cornwell W K. A trait-based approach to community assembly: partitioning of species trait values into within-and among-community components. Ecology Letters, 2007, 10(2): 135- 145.

[85]Lasky J R, Sun I -F, Su S-H, Chen Z-S, Keitt T H. Trait-mediated effects of environmental filtering on tree community dynamics. Journal of Ecology, 2013, 101(3): 722- 733.

[86]Fortunel C, Paine C E T, Fine P V A, Kraft N J B, Baraloto C. Environmental factors predict community functional composition in Amazonian forests. Journal of Ecology, 2014, 102(1): 145- 155.

[87]Gallagher R V, Leishman M R. Contrasting patterns of trait‐based community assembly in lianas and trees from temperate Australia. Oikos, 2012, 121(12): 2026- 2035.

[88]Helsen K, HermyM, Honnay O. Trait but not species convergence during plant community assembly in restored semi-natural grasslands. Oikos, 2012, 121(12): 2121- 2130.

[89]Marteinsdóttir B, Eriksson O. Trait-based filtering from the regional species pool into local grassland communities. Journal of Plant Ecology, 2013, 7(4): 347- 355.

[90]Yan B G, Zhang J, Liu Y, Li Z B, Huang X, Yang W Q, Prinzing A. Trait assembly of woody plants in communities across sub-alpine gradients: Identifying the role of limiting similarity. Journal of Vegetation Science, 2012, 23(4): 698- 708.

[91]Rollinson C R, Kaye M W, Leites L P. Community assembly responses to warming and increased precipitation in an early successional forest. Ecosphere, 2012, 3(12): 122- 122.

[92]Santoro R, Jucker T, Carboni M, Acosta A T R. Patterns of plant community assembly in invaded and non-invaded communities along a natural environmental gradient. Journal of Vegetation Science, 2012, 23(3): 483- 494.

[93]Bennett J A, Lamb E G, Hall J C, Cardinal-McTeague W M, CahillJ F Jr. Increased competition does not lead to increased phylogenetic overdispersion in a native grassland. Ecology Letters, 2013, 16(9): 1168- 1176.

[94]Allan E, Jenkins T, Fergus A J F, Roscher C, Fischer M, Petermann J, Weisser W W, Schmid B. Experimental plant communities develop phylogenetically overdispersed abundance distributions during assembly. Ecology, 2013, 94(2): 465- 477.

[95]Freschet G T, Dias A T C, Ackerly D D, Aerts R, van Bodegom P M, Cornwell W K, Dong M, Kurokawa H, Liu G F, Onipchenko V G, Ordoez J C, Peltzer D A, Richardson S J, Shidakov I I, Soudzilovskaia N A, Tao J P, Cornelissen J H C. Global to community scale differences in the prevalence of convergent over divergent leaf trait distributions in plant assemblages. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2011, 20(5): 755- 765.

[96]Naaf T, Wulf M. Plant community assembly in temperate forests along gradients of soil fertility and disturbance. Acta Oecologica, 2012, 39: 101- 108.

[97]Mason N W H, Richardson S J, Peltzer D A, de Bello F, Wardle D A, Allen R B. Changes in coexistence mechanisms along a long-term soil chronosequence revealed by functional trait diversity. Journal of Ecology, 2012, 100(3): 678- 689.

[98]Katabuchi M, Kurokawa H, Davies S J, Tan S, Nakashizuka T. Soil resource availability shapes community trait structure in a species-rich dipterocarp forest. Journal of Ecology, 2012, 100(3): 643- 651.

[99]Marteinsdóttir B, Eriksson O. Plant community assembly in semi-natural grasslands and ex-arable fields: a trait-based approach. Journal of Vegetation Science, 2013, 25(1): 77- 87.

[100]Roscher C, Schumacher J, Lipowsky A, Gubsch M, Weigelt A, Pompe S, Kolle O, Buchmann N, Schmid B, Schulze E -D. A functional trait-based approach to understand community assembly and diversity-productivity relationships over 7 years in experimental grasslands. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, 2013, 15(3): 139- 149.

[101]Zhang H, Gilbert B, Zhang X X, Zhou S R. Community assembly along a successional gradient in sub-alpine meadows of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. Oikos, 2013, 122(6): 952- 960.

[102]Lohbeck M, Poorter L, Lebrija-Trejos E, Martínez-Ramos M, Meave JA, Paz H, Pérez-García EA, Romero-Pérez I E, Tauro A, Bongers F. Successional changes in functional composition contrast for dry and wet tropical forest. Ecology, 2013, 94(6): 1211- 1216.

[103]Siefert A, Ravenscroft C, Weiser M D, Swenson N G. Functional beta-diversity patterns reveal deterministic community assembly processes in eastern North American trees. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2013, 22(6): 682- 691.

[104]May F, Giladi I, Ristow M, Ziv Y, Jeltsch F. Plant functional traits and community assembly along interacting gradients of productivity and fragmentation. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, 2013, 15(6): 304- 318.

[105]Laliberté E, Norton D A, Scott D. Contrasting effects of productivity and disturbance on plant functional diversity at local and metacommunity scales. Journal of Vegetation Science, 2013, 24(5): 834- 834.

[106]Hulshof C M, Violle C, Spasojevic M J, McGill B, Damschen E, Harrison S, Enquist B J. Intra-specific and inter-specific variation in specific leaf area reveal the importance of abiotic and biotic drivers of species diversity across elevation and latitude. Journal of Vegetation Science, 2013, 24(5): 921- 931.

[108]de Bello F, Lavorel S, Lavergne S, Albert C H, Boulangeat I, Mazel F, Thuiller W. Hierarchical effects of environmental filters on the functional structure of plant communities: a case study in the French Alps. Ecography, 2013, 36(3): 393- 402.

[109]Pottier J, Dubuis A, Pellissier L, Maiorano L, Rossier L, Randin C F, Vittoz P, Guisan A. The accuracy of plant assemblage prediction from species distribution models varies along environmental gradients. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2013, 22(1): 52- 63.

[110]Bhaskar R, Dawson T E, Balvanera P. Community assembly and functional diversity along succession post-management. Functional Ecology, 2014, 28(5): 1256- 1265.

[111]Wellstein C, Campetella G, Spada F, Chelli S, Mucina L, Canullo R, Bartha S. Context-dependent assembly rules and the role of dominating grasses in semi-natural abandoned sub-Mediterranean grasslands. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2014, 182: 113- 122.

[112]Lewis R J, Marrs R H, Pakeman R J. Inferring temporal shifts in landuse intensity from functional response traits and functional diversity patterns: a study of Scotland′s machair grassland. Oikos, 2014, 123(3): 334- 344.

[113]Swenson N G, Stegen J C, Davies S J, Erickson D L, Forero-Montaa J, Hurlbert A H, Kress W J, Thompson J, Uriarte M, Wright S J, Zimmerman J K. Temporal turnover in the composition of tropical tree communities: functional determinism and phylogenetic stochasticity. Ecology, 2012, 93(3): 490- 499.

[114]Ding Y, Zang R G, Letcher S G, Liu S R, He F L. Disturbance regime changes the trait distribution, phylogenetic structure and community assembly of tropical rain forests. Oikos, 2012, 121(8): 1263- 1270.

[115]Purschke O, Schmid B C, Sykes M T, Poschlod P, Michalski S G, Durka W, Küehn I, Winter M, Prentice H C. Contrasting changes in taxonomic, phylogenetic and functional diversity during a long-term succession: insights into assembly processes. Journal of Ecology, 2013, 101(4): 857- 866.

[116]Wang X G, Swenson N G, Wiegand T, Wolf A, Howe R, Lin F, Ye J, Yuan Z Q, Shi S, Bai X J, Xing D L, Hao Z Q. Phylogenetic and functional diversity area relationships in two temperate forests. Ecography, 2013, 36(8): 883- 893.

[117]Pipenbaher N,kornik S, de Carvalho G H, Batalha M A. Phylogenetic and functional relationships in pastures and meadows from the North Adriatic Karst. Plant Ecology, 2013, 214(4): 501- 519.

[118]Liu X J, Swenson N G, Zhang J L, Ma K P. The environment and space, not phylogeny, determine trait dispersion in a subtropical forest. Functional Ecology, 2013, 27(1): 264- 272.

[119]Cadotte M, Albert C H, Walker S C. The ecology of differences: assessing community assembly with trait and evolutionary distances. Ecology Letters, 2013, 16(10): 1234- 1244.

[120]Yang J, Zhang G C, Ci X Q, Swenson N G, Cao M, Sha L Q, Li J, Baskin C C, Slik J W, Lin L X. Functional and phylogenetic assembly in a Chinese tropical tree community across size classes, spatial scales and habitats. Functional Ecology, 2014, 28(2): 520- 529.

[121]Zobel K. On the species-pool hypothesis and on the quasi-neutral concept of plant community diversity. Folia Geobotanica, 2001, 36(1): 3- 8.

[122]Leishman M R. Does the seed size/number trade-off model determine plant community structure? An assessment of the model mechanisms and their generality. Oikos, 2001, 93(2): 294- 302.

[123]Dalling J W, Hubbell S P. Seed size, growth rate and gap microsite conditions as determinants of recruitment success for pioneer species. Journal of Ecology, 2002, 90(3): 557- 568.

[124]Grime J P. Trait convergence and trait divergence in herbaceous plant communities: mechanisms and consequences. Journal of Vegetation Science, 2006, 17(2): 255- 260.

[125]Cornwell W K, Ackerly D D. Community assembly and shifts in plant trait distributions across an environmental gradient in coastal California. Ecological Monographs, 2009, 79(1): 109- 126.

[126]Carboni M, Acosta A T R, Ricotta C. Are differences in functional diversity among plant communities on Mediterranean coastal dunes driven by their phylogenetic history?. Journal of Vegetation Science, 2013, 24(5): 932- 941.

[127]Kraft N J B, Ackerly D D. Functional trait and phylogenetic tests of community assembly across spatial scales in an Amazonian forest. Ecological Monographs, 2010, 80(3): 401- 422.

[128]Zhang J, Hao Z Q, Song B, Li B H, Wang X G, Ye J. Fine-scale species co-occurrence patterns in an old-growth temperate forest. Forest Ecology and Management, 2009, 257(10): 2115- 2120.

[129]Münkemüller T, Gallien L, Lavergne S, Renaud J, Roquet C, Abdulhak S, Dullinger S, Garraud L, GuisanA, Lenoir J, Svenning J-C, Van Es J, Vittoz P, Willner W, Wohlgemuth T, Zimmermann N E, Thuiller W. Scale decisions can reverse conclusions on community assembly processes. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2014, 23(6): 620- 632, doi:10.1111/geb.12137.

[130]Silva I A, Batalha M A. Phylogenetic overdispersion of plant species in southern Brazilian savannas. Brazilian Journal of Biology, 2009, 69(3): 843- 849.

[131]Willis C G, Halina M, Lehman C, Reich P B, Keen A, McCarthy S, Cavender-Bares J. Phylogenetic community structure in Minnesota oak savanna is influenced by spatial extent and environmental variation. Ecography, 2010, 33(3): 565- 577.

[132]Vamosi S M, Heard S B, Vamosi J C, Webb C O. Emerging patterns in the comparative analysis of phylogenetic community structure. Molecular Ecology, 2009, 18(4): 572- 592.

[133]Letcher S G. Phylogenetic structure of angiosperm communities during tropical forest succession. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2010, 277(1678): 97- 104.

[134]Kembel S W, Hubbell S P. The phylogenetic structure of a neotropical forest tree community. Ecology, 2006, 87(S7): S86-S99.

[135]Lecerf A, Chauvet E. Intraspecific variability in leaf traits strongly affects alder leaf decomposition in a stream. Basic and Applied Ecology, 2008, 9(5): 598- 605.

[136]Laughlin D C, Laughlin D E. Advances in modeling trait-based plant community assembly. Trends in Plant Science, 2013, 18(10): 584- 593.

[137]Ridley M. Evolution. Malden, MA:Blackwell Scientic Publishing, 2003.

[138]Jung V, Violle C, Mondy C, Hoffmann L, Muller S. Intraspecific variability and trait-based community assembly. Journal of Ecology, 2010, 98(5): 1134- 1140.

[139]Albert C H, Thuiller W, Yoccoz N G, Douzet R, Aubert S, Lavorel S. A multi-trait approach reveals the structure and the relative importance of intra- vs. interspecific variability in plant traits. Functional Ecology, 2010, 24(6): 1192- 1201.

[140]Xiao S, Michalet R, Wang G, Chen S Y. The interplay between species′ positive and negative interactions shapes the community biomass-species richness relationship. Oikos, 2009, 118(9): 1343- 1348.

[141]Wright I J, Reich P B, Westoby M, Ackerly D D, Baruch Z, Bongers F, Cavender-Bares J, Chapin T, Cornelissen J H C, Diemer M, Flexas J, Garnier E, Groom P K, Gulias J, Hikosaka K, Lamont B B, Lee T, Lee W, Lusk C, Midgley J J, Navas M -L, Niinemets Ü, Oleksyn J, Osada N, Poorter H, Poot P, Prior L, Pyankov V I, Roumet C, Thomas S C, Tjoelker M G, Veneklaas E J, Villar R. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature, 2004, 428(6985): 821- 827.

[142]Laughlin D C. The intrinsic dimensionality of plant traits and its relevance to community assembly. Journal of Ecology, 2014, 102(1): 186- 193.

[143]Shipley B. From Plant Traits to Vegetation Structure: Chance and Selection in the Assembly of Ecological Communities. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

[144]Westoby M, Falster D S, Moles A T, Vesk P A, Wright I J. Plant ecological strategies: some leading dimensions of variation between species. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 2002, 33: 125- 159.

[145]Wright S J, Kitajima K, Kraft N J B, Reich P B, Wright I J, Bunker D E, Condit R, Dalling J W, Davies S J, Díaz S, Engelbrecht B M J, Harms K E, Hubbell S P, Marks C O, Ruiz-Jaen M C, Salvador C M, Zanne A E. Functional traits and the growth-mortality trade-off in tropical trees. Ecology, 2010, 91(12): 3664- 3674.

[146]Fortunel C, Fine P V, Baraloto C. Leaf, stem and root tissue strategies across 758 Neotropical tree species. Functional Ecology, 2012, 26(5): 1153- 1161.

[147]Hegland S J, Nielsen A, Lázaro A, Bjerknes A -L, Totland Ø. How does climate warming affect plant-pollinator interactions?. Ecology Letters, 2009, 12(2):184- 195.

[148]Weiher E, van der Werf A, Thompson K, Roderick M, Garnier E, Eriksson O. Challenging theophrastus: a common core list of plant traits for functional ecology. Journal of Vegetation Science, 1999, 10(5):609- 620.

[149]Westoby M, Wright I J. Land-plant ecology on the basis of functional traits. Trends in Ecology &Evolution, 2006, 21(5):261- 268.

[150]Crutsinger G M, Collins M D, Fordyce J A, Gompert Z, Nice C C, SandersN J. Plant genotypic diversity predicts community structure and governs an ecosystemprocess. Science, 2006, 313(5789): 966- 968.

[151]Adler P B, Fajardo A, Kleinhesselink A R, Kraft N J B. Trait-based tests of coexistence mechanisms. Ecology Letters, 2013, 16(10): 1294- 1306.

[152]Boege K, Dirzo R. Intraspecific variation in growth, defense and herbivory inDialiumguianense(Caesalpiniaceae) mediated by edaphic heterogeneity. Plant Ecology, 2004, 175(1): 59- 69.

Research advances in plant community assembly mechanisms

CHAI Yongfu, YUE Ming*

KeyLaboratoryofResourceBiologyandBiotechnologyinWesternChina,NorthwestUniversity,Xi′an710069,China

The study of plant community assembly is integral for understanding species coexistence and biodiversity maintenance, and it has long been a central issue in community ecology. The mechanistic theories of community assembly generally fall into two classes: niche theory and neutral theory. Although validation studies of niche theory and neutral theory have achieved great advances in recent years, some difficulty remains in understanding the mechanisms of local community assembly. Advances in statistics and theory make it possible to infer community assembly mechanisms based on functional traits and phylogenetic structures, by testing the dispersion patterns of trait and phylogenetic distance among co-occurring species. Both trait and phylogenetic community methods share the same conceptual approach. The observed distribution of either traits or phylogenetic distances within a local community is compared to a null expectation generated by drawing species at random from a regional pool of potential colonists. Deviations from the null expectation can be used as evidence for a number of ecological processes in the assembly of the local community. Both the approaches for measuring species differences can be aggregated at the community level to summarize the degree to which the constituent species differ in terms of their function, niche, or evolutionary history. However, traits and phylogenies provide different, and perhaps complementary, information in understanding patterns of community assembly. To adequately test assembly hypotheses, a framework integrating the information provided by functional traits and phylogenies is required. In addition, many biotic and abiotic factors (competition, facilitation) control community assembly. Different factors shape the distribution and abundance of species at different spatial and temporal scales. Multiple processes, including dispersal limitation based on neutral theory, and environmental filtering and limiting similarity based on niche theory, may simultaneously affect community assembly. The relative importance of these processes will differ among communities. The same process may cause opposing diversity patterns, and the same pattern may result from different processes. Therefore, it is important to simultaneously consider multiple methods and influence factors when exploring mechanisms of plant community assembly, predicting plant response to disturbance, and understanding biodiversity maintenance. In this paper, we provide a review of the histories, theories, methods, and new advances in community assembly explanations. We discuss ways to explain plant community assembly mechanisms by integrating functional trait and phylogenetic structure methods. We argue that time scale, number and type of traits, intraspecies trait variation, and interference should be considered in a study of community assembly, but spatial scale, environmental factors, and vegetation type need not be considered.

community assembly; function traits; phylogenetic structure; habitat filtering; limiting similarity

华北地区自然植物群落资源综合考察——陕西、甘肃子课题(2011FY110300);陕西省教育厅重点实验室科研项目计划(JH10256);国家自然科学基金(41571500)

2015- 01- 14; 网络出版日期:2015- 11- 17

Corresponding author.E-mail: yueming@nwu.edu.cn

10.5846/stxb201501140114

柴永福, 岳明.植物群落构建机制研究进展.生态学报,2016,36(15):4557- 4572.

Chai Y F, Yue M.Research advances in plant community assembly mechanisms.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2016,36(15):4557- 4572.