CO2浓度升高和氮素供应对黄瓜叶片光合色素的影响①

2016-10-11董金龙段增强土壤与农业可持续发展国家重点实验室中国科学院南京土壤研究所南京20008中国科学院大学北京00049

宝 俐,董金龙,李 汛,段增强*( 土壤与农业可持续发展国家重点实验室 (中国科学院南京土壤研究所),南京 20008;2 中国科学院大学,北京 00049)

CO2浓度升高和氮素供应对黄瓜叶片光合色素的影响①

宝 俐1, 2,董金龙1, 2,李 汛1,段增强1*

(1 土壤与农业可持续发展国家重点实验室 (中国科学院南京土壤研究所),南京 210008;2 中国科学院大学,北京 100049)

本文通过N供应浓度[2(低N),7(中N)和14(高N)mmol/L]和CO2浓度[400 (C1),625 (C2),1 200 (C4)μmol/mol] 处理的水培试验一,以及硝铵比[14/0(N1),13/1(N2),11/3(N3)和 8/6(N4)]和CO2浓度[400 (C1),800 (C3),1 200 (C4) μmol/mol]处理的水培试验二,共同研究黄瓜叶片光合色素对CO2升高、N供应浓度和形态的响应。研究结果表明:苗期时,低、中和高N下,C4处理使得植物干物质都明显增加;而初果期干物质提高程度下降,植株生长速率降低。中等CO2浓度(C3)显著增加植物在各硝铵比处理的干物质量,但最高CO2浓度(C4)有提高N3处理的干物质量的趋势。苗期时,在低N和中N供应时C4处理显著降低叶片叶绿素a、叶绿素b和胡萝卜素含量;但高N时,C3处理提高总色素含量,C4处理提高叶绿素b含量;初果期时CO2浓度处理对色素含量无显著影响;N2硝铵比处理,中等CO2浓度(C3)下叶片的3种色素含量最高。因此当苗期N素供应浓度较低时,CO2浓度升高会显著降低叶片3种色素的含量,这主要可能与苗期植物生长速率显著提高产生的稀释作用有关。当N浓度为14 mmol/L时,CO2浓度适当提高显著促进色素合成,其合成速率大于植物生长速率,导致色素含量提高,提高光合能力;初果期时,CO2浓度升高的促进作用降低缓和了色素浓度的下降。适当提高 NH4+-N供应比例也能达到提高色素含量的效果,但 CO2浓度不宜过高。故而植物光合色素含量可能受到CO2浓度升高导致的植物干物质增加速率和光合色素合成速率改变的双重调节。中N和高N供应时,叶绿素a/b 在苗期随着CO2浓度的升高而降低,在初果期仅在高N时有显著降低。而在硝铵比试验中,植株种植稀疏时,C4处理提高叶绿素a/b。因此,CO2浓度升高下的植物捕光能力的提高,可通过适当降低叶片光照强度和提高N供应浓度来实现。从实际生产角度出发,使用中等浓度CO2施肥,提高N肥供应浓度和NH4+-N比例,结合植株的适当密植更有利于光合色素含量提高,优化其组成,从而有利于黄瓜生物量的提高。

CO2施肥;硝铵比;生长速率;色素合成速率;密植

植物叶片中的光合色素是一类含 N化合物,叶片色素含量较低时,通常表现为叶片的黄化,这也是缺N的重要标志之一[1]。近年来,CO2浓度的升高对植物生长的影响广受关注, 其中大量研究表明 CO2浓度的升高会导致植物N含量的下降[2-3]。由于N浓度与色素含量高度相关,较多研究证实 CO2浓度升高会导致色素含量的下降[4-7];但也有研究表明 CO2浓度升高并不影响叶片色素含量[8-10]。由于CO2浓度升高对光合色素合成过程的研究较少,加之色素合成过程受到光照强度、植物种类等因素的影响[11-12],CO2浓度升高对光合色素含量及组成的影响程度的研究结果各有不同。另一方面,现有对色素含量变化原因的解释还众说纷纭:对于并不肥沃的森林土壤,研究学者多认为 CO2浓度升高在提高植物生产率的同时造成土壤有效N含量下降,产生进一步N限制现象[13]。因此植物因为供N不足而极易导致色素含量下降;也有研究认为色素等物质含量的下降是由于碳水化合物的过量积累产生的稀释作用所导致的[14]。

虽然已经基本明确 N含量的变化是导致光合色素含量变化的原因之一,而且适当提高NH-N供应也有助于提高叶片色素含量[15],但这方面的实际应用研究并不多见。由于我国设施蔬菜种植面积的不断扩大,设施 CO2施肥研究也不断深入[16-17],但 CO2施肥对设施生产中黄瓜的光合色素变化还较少有报道。同时我国设施栽培中大量施用 N肥,却无法有效提高作物光合效率的现状日益严峻[18]。如何通过合理的N肥用量和铵硝比控制,配合CO2施肥从而获得更高的蔬菜产量成为研究热点。本文旨在研究黄瓜叶片光合色素对 CO2升高、N供应浓度和形态的响应,探讨光合色素含量变化的原因及如何进行合理的N肥和CO2施肥以提高叶片光合色素含量并优化其组成,从而提高黄瓜的光合生产效率和产量。

1 材料与方法

1.1 试验设计

试验一:CO2设3个浓度水平,为400(对照,大气CO2浓度,C1)、625(C2)、1 200 (C4) μmol/mol;NO-N浓度设3个水平,分别为2(低N)、7(中N)和14(高N)mmol/L。试验二:CO2设3个浓度水平,为400(C1),800(C3),1 200 (C4) μmol/mol;硝铵比设4个水平,分别为 14/0(N1)、13/1(N2)、11/3(N3) 和8/6(N4)。

试验在中国科学院南京土壤研究所温室内 3个开顶式生长箱(OTCs)进行。CO2浓度的控制使用自主设计的 CO2自动控制系统:系统将 99.99% 纯度的CO2气体通过与空气混合配气形成3 000 μmol/molCO2气体通入开顶式生长箱,然后由一台红外 CO2检测器检测生长箱内气体浓度,达到预设浓度即由电磁阀控制停止气体通入,低于预设浓度时即再次通入气体。CO2浓度控制精度可以保证在 90% 时间内达到 ±50 μmol/mol。试验皆为两因素随机区组设计;试验每个处理设有6个重复。

1.2 试验方法

将黄瓜种子(江苏南京金丰种苗有限公司购买)用 10% 的次氯酸钠消毒 15 min,完全清洗后置于25℃ 恒温培养室中催芽,种子露白播种于装有培养基质的育苗盘内。黄瓜苗长到两叶一心时,定植于容量为1 L的PVC栽培罐中。定植后第二天开始进行CO2施肥,从8:00开始到18:00结束。栽培罐中装有改良的山崎黄瓜营养液,微量元素使用Arnon营养液通用配方[19]。前两周使用1/2营养液,以后使用全营养液栽培。为保证根系氧气充足供应,栽培罐内每日进行通气处理,6:00—18:00,每小时通气30 min;18:00至次日6:00,每两小时通气30 min。每日下午17:00左右,营养液消耗大于100 ml时,用配制的各处理营养液补足,每周更换一次营养液。期间每天使用0.1 mmol/L的NaOH和0.05 mmol/L 的 H2SO4调节pH至6.50。全生长期由温湿度自动记录仪(L95-82,杭州路格科技有限公司)每30 min记录一次温湿度数据;光照记录仪(L99-LX,杭州路格科技有限公司)每10 min自动记录一次光照数据。

试验一在2013年4—6月进行。每个栽培罐定植两株幼苗。营养液大量元素组成见表1。黄瓜定植后16天和50天分别采收一次植株。3个OTCs生长箱内的温度分别为 (23.6±5.0)℃、(24.1±5.0)℃ 和(24.1±5.2) ℃;湿度分别为71.4%±20.1%、73.4%± 18.5% 和 74.1%±18.4%。全生长期光照强度皆为(4 010±6 590) lx(平均值±标准差)。

试验二在2014年2—4月进行。每个栽培罐定植一株幼苗。营养液大量元素组成见表2。黄瓜植株定植51天后采收全部植株。3个OTCs生长箱内的温度分别为 (18.9±6.6)℃、(19.0±6.4) ℃和(18.9± 6.8) ℃;湿度为68.7%±21.5%、68.3%±21.0% 和67.5%±21.2%;光照强度皆为 (9 580±16 530) lx(平均值±标准差)。

表1 三种NO3--N处理的营养液大量元素组成(mmol/L)Table1 Components of macro-elements of three nitrate nutrient solutions

表2 四种硝铵比处理的营养液大量元素组成(mmol/L)Table2 Components of macro-elements of four N nutrient solutions

1.3 测定方法

收获的植物样品分成根、茎、叶和果实,一部分在100℃杀青15 min,70℃ 烘干至恒重,称其干重。另外取部分混合新鲜叶片冷冻干燥,研磨储存备用。植物叶片叶绿素a、叶绿素b和胡萝卜素含量通过95%乙醇提取,使用微孔板分光光度计(Epoch, USA)测定[20]。

1.4 数据分析

试验数据用Microsoft Excel 2007和IBM SPSS19统计软件进行统计分析,Tukey法进行多重比较。

2 结果与分析

2.1 干物质对CO2、N供应的响应

苗期时,低、中和高N下植物在C4处理后干物质分别增加了54.5%,63.6% 和77.2%(表3,图1A)。而初果期后,仅低N和高N时,C4处理对干物质有显著提高。C3处理使得植物干物质在N1、N2、N3和N4硝铵比下显著增加且干物质量最高,且在N3硝铵比时,C4处理的干物质量较C3处理仍有增加但不显著。

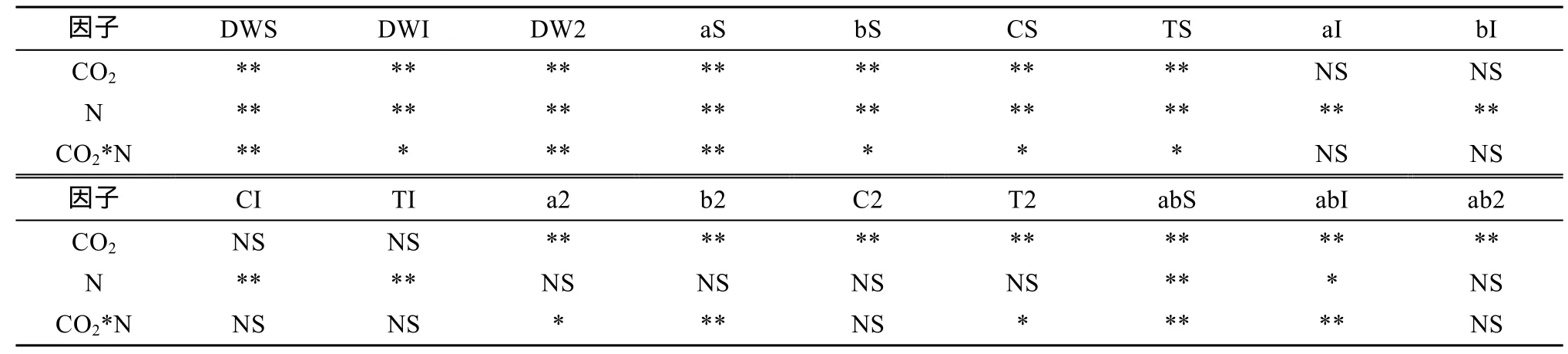

表3 试验各指标方差分析结果Table3 Results of ANOVA of indexes in two experiments

图1 黄瓜的全株干重Fig. 1 Dry weight of the entire cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.)

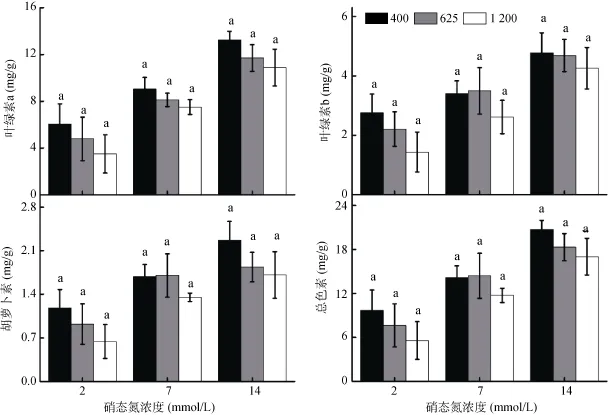

2.2 色素含量对CO2和N供应浓度的响应

苗期时,在低N和中N供应时C4处理显著降低叶片叶绿素a、叶绿素b和胡萝卜素含量(图2)。但在高N时,C4处理提高叶绿素b含量,C3处理提高总色素含量。初果期时,提高 N供应浓度有利于色素含量的提高,但 CO2浓度升高有降低色素含量的趋势(并不显著,图3)。

2.3 色素含量对CO2和硝铵比变化的响应

对比3个CO2浓度水平,C3处理使得叶片在N2硝铵比下具有最高的3种色素含量(图4,表3);在N3硝铵比下,C4处理有提高叶绿素a和胡萝卜素含量的趋势。N4时,色素含量受CO2浓度影响并不显著。C1处理时,N4硝铵比处理的叶片较其他3个N处理具有更高的色素含量。

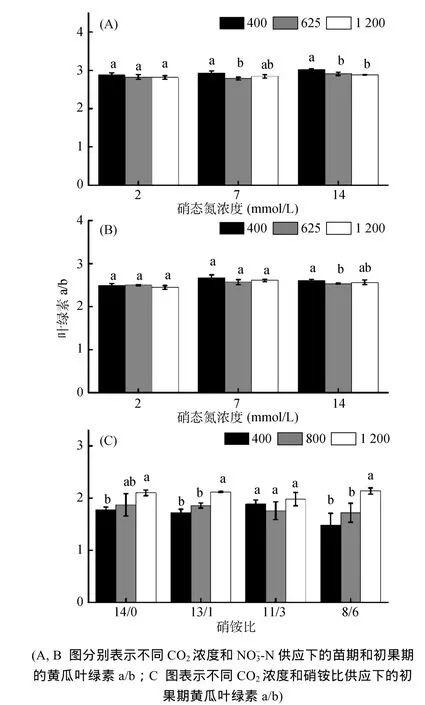

2.4 色素组成对CO2、N供应的响应

中N和高N供应时,叶绿素a/b 在苗期随着CO2浓度的升高而降低;在初果期其仅在高 N时有显著降低(图5,表3)。而在硝铵比试验中,C4处理提高叶绿素a/b,仅在N3时表现得并不显著。

3 讨论

CO2是光合作用的底物,其浓度的升高促进植物的光合作用,提高作物的生产效率和产量[3],这种响应受到 N素供应的正调控[21],本研究中黄瓜的干物质积累结果与此相符。CO2浓度升高增加干物质量的原因在于在单位时间内,CO2浓度升高促进了植物生长速率的提高。作为一种气肥CO2的生长刺激作用与化学肥料类似,在促进植物快速生长的同时会稀释植物体内矿质元素等物质的含量[22-23]。这种现象的本质是:植物在环境有益刺激下光合碳同化效率大于该物质吸收或者合成的效率。现有研究广泛重视的植物体内矿质元素含量下降即是例证。虽然元素含量下降与元素种类、元素吸收和元素功能都有联系,但光合产物大量合成产生的“稀释效应”仍然是重要的原因之一[14,24]。

图2 苗期不同CO2和NO-N供应浓度下黄瓜叶片的叶绿素a、叶绿素b、胡萝卜素和总色素含量Fig. 2 Chlorophyll a, b, carotenoids and total pigments in leaves of cucumber grown under various CO2concentrations and nitrate supplyrates at seedling stage

图3 初果期不同CO2和NO-N供应浓度下黄瓜叶片的叶绿素a、叶绿素b、胡萝卜素和总色素含量Fig. 3 Chlorophyll a, b, carotenoids and total pigments of leaves of cucumber grown under various CO2concentrations and nitrate supply rates at initial fruit stage

图4 初果期不同CO2和硝铵比供应下黄瓜叶片的叶绿素a、叶绿素b、胡萝卜素和总色素含量Fig. 4 Chlorophyll a, b, carotenoids and total pigments of leaves of cucumber grown under various CO2concentrations and nitrate/ammomium ratios at initial fruit stage

本研究中叶片光合色素含量的下降与“稀释效应”密切相关。光合色素的合成强烈依赖N素供应[1,12],N的吸收成为色素合成的决定因素(本文叶片N含量与总色素含量呈极显著正相关(P<0.01),且变化趋势一致,未给出数据)。当植物N素供应较低时,CO2浓度升高在加剧 N含量下降的同时降低色素合成。由于植物处在苗期,营养生长旺盛,植物 N含量的下降往往不能同等程度地限制CO2的固定效率[7]。因此低 N供应的苗期,光合碳固定对色素含量的“稀释效应”最显著(图2)。当植物处于生殖生长期时,CO2作用时间延长,CO2刺激效应下降,植物生长速率下降,相应的“稀释效应”也下降(图3)。另一方面在最高的NH-N供应处理下,植物产生了铵毒害,从而抑制黄瓜干物质的增加,降低黄瓜生长速率,“稀释效应”下降剧烈,从而也并不降低色素含量(图4)。

光合色素含量下降除了受到“稀释效应”的影响,植物N代谢及色素合成下降也可能是原因之一。当N素供应充足时,色素含量并不下降,CO2浓度升高反而显著促进叶绿素b的合成(图2)。CO2浓度升高能够提高植物叶面积,增加叶片重叠度而不利于光照接收,可能反馈刺激叶绿素b的合成[25-26]。NHN的提高也能够促进CO2浓度升高下的植物N代谢,从而有利于色素的合成[27-28]。本研究发现,正常 CO2浓度下植株正常生长时,NHN供应提高有降低色素含量的趋势,但在高 CO2浓度时,NHN供应能够提高色素含量(图4),提高CO2浓度与提高NHN比例配合更有利于色素含量提高;另外,适当提高CO2浓度至800 μmol/mol最有利于N素和光合色素合成(图4)。由于CO2浓度升高产生的光合适应现象,最高的CO2浓度(1 200 μmol/mol)不利于植物生长和养分代谢[29-30]。在高 CO2作用时间长的初果期,植物 N限制极为强烈[13,31],光合色素合成会下降,若非光合碳固定下降,此时色素浓度可能会显著降低(图3)。再者本研究试验二每个栽培罐仅有一棵植株,相对试验一减少,因此供 N强度相对更大,光合色素合成能力更强烈。但此时处于生殖生长期的植株生长速率也相对较低,综合导致了叶绿素a、叶绿素b和胡萝卜素合成量与植物生物量变化相近。在 N供应强度高时,虽然光合产物的“稀释效应”仍然降低色素含量,但 CO2浓度升高对光合色素合成的促进作用可能成为主导因素。

本研究中,光合色素的组成也有显著的变化(图5),其中叶绿素a/b是重要的捕光能力衡量指标,其变化受到光照和N有效性两个因素的影响[32-33]。CO2浓度升高一方面促进植物叶面积增加,降低叶片可获得光照,相对促进叶绿素 b合成,进而降低叶绿素a/b[34];另一方面CO2浓度升高也降低N浓度,增加叶绿素a/b[12]。试验一中N素供应相对较高时,叶绿素a/b有明显下降,表明在N素供应较高时,CO2升高对叶面积增加的促进效果更为显著,更显著降低叶绿素a/b,提高植物捕光能力;而试验二中,由于仅有一株植物,叶片遮光程度影响较小,而 CO2浓度升高对 N素浓度的下降程度影响显著,因此提高叶绿素a/b的值。因为此时植物间距小,植物叶片接受到的高光强与高CO2浓度协同作用,光合物质合成更多,植物可能降低叶绿素b合成,降低捕光能力,进行反馈调节,从而减少过多光合物质积累的危害[12,29]。总之,从生产角度考虑,CO2浓度升高后植物适当密植,同时提高 N供应浓度更有利于获得更高的生产效率。

图5 黄瓜叶片的叶绿素a/b的变化Fig. 5 Chlorophyll a/b of leaves of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.)

4 结论

植物光合色素含量可能受 CO2浓度升高导致的植物生长速率和光合色素合成速率改变的双重调节。当 N素供应浓度较低时,CO2浓度升高会明显降低叶片叶绿素a、叶绿素b和胡萝卜素的含量。这主要是植物生长速率显著提高产生的稀释作用导致。当N

素供应浓度较高时,CO2浓度适当提高同时会显著促进色素合成,且这一速率可能大于植物生长速率,导致色素含量提高。CO2浓度升高下可以通过适当降低作物间距,增加总N供应浓度和NH4+-N比例,提高植物叶片含 N量和植物捕光能力,以期获得更高的作物产量;同时需要控制 CO2浓度过高产生的反馈抑制现象。

[1] Marschner P. Marschner's mineral nutrition of higher plants[M]. 3rd Edition. London: Academic Press, 2012:135-248

[2] Cotrufo M F, Ineson P, Scott A Y. Elevated CO2reduces the nitrogen concentration of plant tissues[J]. Global Change Biology, 1998, 4(1): 43-54

[3] Leakey A D B, Ainsworth E A, Bernacchi C J, et al. Elevated CO2effects on plant carbon, nitrogen, and water relations: Six important lessons from FACE[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2009, 60(10): 2 859-2 876

[4] Bindi M, Hacour A, Vandermeiren K, et al. Chlorophyll concentration of potatoes grown under elevated carbon dioxide and/or ozone concentrations[J]. European Journal of Agronomy, 2002, 17(4): 319-335

[5] Houpis J L, Surano K A, Cowles S, et al. Chlorophyll and carotenoid concentrations in two varieties of Pinus ponderosa seedlings subjected to long-term elevated carbon dioxide[J]. Tree Physiology, 1988, 4(2): 187-193

[6] Murray M B, Smith R I, Friend A, et al. Effect of elevated [CO2] and varying nutrient application rates on physiology and biomass accumulation of Sitka spruce (Piceasitchensis)[J]. Tree Physiology, 2000, 20(7): 421-434

[7] Wullschleger S, Norby R, Hendrix D. Carbon exchange rates, chlorophyll content, and carbohydrate status of two forest tree species exposed to carbon dioxide enrichment[J]. Tree Physiology, 1992, 10(1): 21-31

[8] Donnelly A, Craigon J, Black C R, et al. Does elevated CO2ameliorate the impact of O3on chlorophyll content and photosynthesis in potato (Solanum tuberosum)?[J]. Physiologia Plantarum, 2001, 111(4): 501-511

[9] Donnelly A, Jones M B, Burke J I, et al. Elevated CO2provides protection from O3induced photosynthetic damage and chlorophyll loss in flag leaves of spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L., cv. ‘Minaret')[J]. Agriculture,Ecosystems & Environment, 2000, 80(1/2): 159-168

[10] Koti S, Reddy K R, Kakani V, et al. Effects of carbon dioxide, temperature and ultraviolet-B radiation and their interactions on soybean (Glycine max L.) growth and development[J]. Environmental and Experimental Botany,2007, 60(1): 1-10

[11] Danesi E D G, Rangel-Yagui C O, Carvalho J C M, et al. Effect of reducing the light intensity on the growth and production of chlorophyll by Spirulina platensis[J]. Biomass Bioenergy, 2004, 26(4): 329-335

[12] Kitajima K, Hogan K P. Increases of chlorophyll a/b ratios during acclimation of tropical woody seedlings to nitrogen limitation and high light[J]. Plant Cell & Environment,2003, 26(6): 857-865

[13] Luo Y, Su B, Currie W S, et al. Progressive nitrogen limitation of ecosystem responses to rising atmospheric carbon dioxide[J]. Bioscience, 2004, 54(8): 731-739

[14] Gifford R, Barrett D, Lutze J. The effects of elevated [CO2]on the C:N and C:P mass ratios of plant tissues[J]. Plant & Soil, 2000, 224(1): 1-14

[15] Sandoval-Villa M, Guertal E A, Wood C W. Tomato leaf chlorophyll meter readings as affected by variety, nitrogen form, and nighttime nutrient solution strength[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 2000, 23(5): 649-661

[16] Jin C, Du S, Wang Y, et al. Carbon dioxide enrichment by composting in greenhouses and its effect on vegetable production[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science,2009, 172(3): 418-424

[17] 喻景权. “十一五” 我国设施蔬菜生产和科技进展及其展望[J]. 中国蔬菜, 2011(2): 11-23

[18] 陆扣萍, 闵炬, 施卫明, 等. 填闲作物甜玉米对太湖地区设施菜地土壤硝态氮残留及淋失的影响. 土壤学报,2013, 50(2): 109-117

[19] 郭世荣. 无土栽培学[M]. 北京: 中国农业出版社, 2003:98

[20] Hartmut K. Determinations of total carotenoids and chlorophyll a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents[J]. Biochemical Society transactions, 1983, 11: 591-592

[21] Stitt M, Krapp A. The interaction between elevated carbon dioxide and nitrogen nutrition: The physiological and molecular background[J]. Plant Cell & Environment, 1999,22(6): 583-621

[22] Davis D R. Declining fruit and vegetable nutrient composition: What is the evidence?[J]. Hort Science, 2009,44(1): 15-19

[23] Taub D R, Wang X. Why are nitrogen concentrations in plant tissues lower under elevated CO2? A critical examination of the hypotheses[J]. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 2008, 50(11): 1 365-1 374

[24] Duval B, Blankinship J, Dijkstra P, et al. CO2effects on plant nutrient concentration depend on plant functional group and available nitrogen: A meta-analysis[J]. Plant Ecology, 2012, 213(3): 505-521

[25] Hikosaka K, Terashima I. A model of the acclimation of photosynthesis in the leaves of C3 plants to sun and shade with respect to nitrogen use[J]. Plant Cell & Environment,1995, 18(6): 605-618

[26] Pal M, Rao L S, Jain V, et al. Effects of elevated CO2and nitrogen on wheat growth and photosynthesis[J]. Biologia Plantarum, 2005, 49(3): 467-470

[27] Bloom A J, Burger M, Asensio J S R, et al. Carbon dioxide enrichment inhibits nitrate assimilation in wheat and Arabidopsis[J]. Science, 2010, 328(5980): 899-903

[28] Bloom A J, Smart D R, Nguyen D T, et al. Nitrogen assimilation and growth of wheat under elevated carbon dioxide[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2002, 99(3): 1 730-1 735

[29] Cruz J L, Alves A A C, LeCain D R, et al. Effect of elevated CO2concentration and nitrate: Ammonium ratios on gas exchange and growth of cassava (Manihotesculenta Crantz)[J]. Plant & Soil, 2014, 374(1-2): 33-43

[30] Kirschbaum M U. Does enhanced photosynthesis enhance growth? Lessons learned from CO2enrichment studies[J]. Plant Physiology, 2011, 155(1): 117-124

[31] McGrath J M, Lobell D B. Reduction of transpiration and altered nutrient allocation contribute to nutrient decline of crops grown in elevated CO2concentrations[J]. Plant Cell & Environment, 2013, 36(3): 697-705

[32] Jinwen L, Jingping Y, Pinpin F, et al. Responses of rice leaf thickness, SPAD readings and chlorophyll a/b ratios to different nitrogen supply rates in paddy field [J]. Field Crop Research, 2009, 114(3): 426-432

[33] Marschall M, Proctor M C. Are bryophytes shade plants?Photosynthetic light responses and proportions of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b and total carotenoids[J]. Annals of Botany, 2004, 94(4): 593-603

[34] Dale M, Causton D. Use of the chlorophyll a/b ratio as a bioassay for the light environment of a plant[J]. Functional Ecology, 1992, 6(2): 190-196

Effects of Elevated CO2, N Concentration and N Forms on Photosynthetic Pigments Concentration and Composition

BAO Li1,2, DONG Jinlong1,2, LI Xun1, DUAN Zengqiang1*

(1 State Key Laboratory of Soil and Sustainable Agriculture (Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences), Nanjing 210008, China; 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China)

This study consisted of two experiments to study the leaf photosynthetic pigment concentrations of cucumber. The first one studied the effects of elevated CO2and nitrate concentration under three nitrate concentrations [2(low N),7(moderate N) and 14(high N) mmol/L] and three CO2concentrations [400 (C1), 625 (C2) and 1 200 (C4) μmol/mol]. The second one studied the effects of elevated CO2and N forms under three CO2concentrations [400 (C1), 800(C3) and 1200 (C4) μmol/mol]and four ratios of nitrate to ammonium concentrations [14/0(N1), 13/1(N2), 11/3 (N3) and 8/6(N4)]. The results showed that: at the seedling stage, C4 treatment enhanced the biomass of all the three N supplies and this effect decreased at the initial fruit stage. The biomass of C3 treatment increased and was the highest among the CO2treatments. At the seedling stage, the chlorophyll a, b and carotenoids concentrations of the low and moderate N increased under C3 treatment, while high N increased the chlorophyll b and total pigment concentrations. Three pigment concentrations of N2 treatment were the highest under C3 treatment, while their concentrations in N3 treatment were the highest under C4 treatment among the CO2treatments. Thus, at the seedling stage,elevated CO2decreased three pigment concentrations of low N due to “dilution effect” caused by the high growth rate. But when N concentration was 14 mmol/L, elevated CO2increased the pigment synthesis and this rate was higher than the growth rate,which resulted in higher pigment concentrations. This effect also existed with high ammonium supply. The pigment concentration was generally controlled by the growth rate and pigments synthesis rate simultaneously. Under moderate and high N, chlorophyll a/b at the seedling stage increased under high CO2, but only that of the high N decreased at the initial fruit stage. Moreover, C4 treatment enhanced chlorophyll a/b, which may be enhanced by high light density and low N concentration. Practically, the cucumber cultivation under elevated CO2should combine with high N concentration, high ammonium supply rates and high plant density.

CO2fertilization; Nitrate to ammonium ratio; Growth rate; Pigment synthesis rate; High plant density

S627;Q945.18

10.13758/j.cnki.tr.2016.04.005

国家自然科学基金项目(41101272)和国家科技支撑计划项目(2014BAD14B04)资助。

(zqduan@issas.ac.cn)

宝俐(1992—),女,江苏扬州人,硕士研究生,主要从事植物营养与土壤生态研究。E-mail: baoli@issas.ac.cn