WHAT A TANGLED WEB WE WEAVE...

2016-09-22

WHAT A TANGLED WEB WE WEAVE...

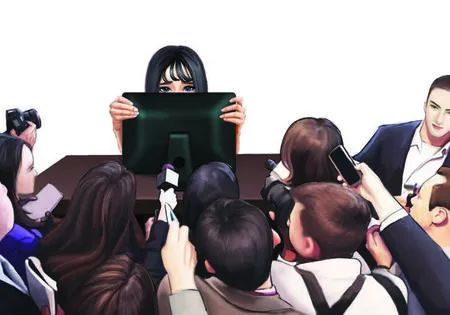

WHEN IT COMES TO ONLINE CELEBRITY, SHAME LEADS TO FAME

Probably the most notable—and certainly the most notorious—web celebrity at present is Wang Sicong, the big-spending, big-mouthed son of the richest man in China, Dalian Wanda Group CEO Wang Jianlin.

As the heir to what is now a 32.7 billion USD fortune, the younger Wang had long been a well-known name, but it wasn’t until 2011 that he made his first big splash in the world of online gossip. In April of that year he got into a spat on Sina Weibo when he accused Zhang Lan, owner of the high-end South Beauty restaurant chain, of lying about being close friends with his father and accepting money from the Wanda Group for her son’s wedding. A few days later he called Zhang and her son “zhuangbi”, a vulgar term for people that exaggerate their worth.

Though it garnered buzz at the time, this wasn’t Wang’s first spat; in January of 2011 alone he fired pointed barbs at venture capitalist Kai-Fu Lee for releasing a book with an“ugly” cover and called comedian Zhao Benshan a nongmin, or peasant, for renting out a plane he’d bought. It was, however, big enough to be commented on by local media, an indicator of things to come.

As the years rolled by, Wang’s infamy grew thanks to both outlandish displays of wealth and his knack for hitting the nerves of web users. On Valentine’s Day last year, he announced that all he needs in a Valentine date is big boobs; the fuss created led to state media organization Xinhua publishing a 1,287-word criticism claiming that Wang: “recklessly disseminates vulgar information…from the worship of money to sex and violence”. His father apologized for Wang’s behavior on state television, blaming his son’s Western education for his outspoken nature.

Perhaps they hoped it would shame him into silence. If so, they were wrong: Wang reposted the article on his Weibo account, and one month later he posted a picture of him straddling his pet huskie, with the caption “I am practicing how to fuck a dog”. Xinhua squealed that he’d, “stained the purity of the Chinese” and warned others not to praise or copy him. Regardless, he continued to hit the headlines; in May he showed off two Apple watches he’d bought for his dog, and in June he got into a slanging match with actress Fan Bingbing.

Whether Wang gets off on trolling the uptight and pompous by playing a character, or whether his Weibo feed is an honest gateway to an id unleashed is up for debate. What’s certain is that his outlandish acts have made him enormously popular. He has a following of 15 million Weibo fans, and is known as “The People’s Husband” (国民老公)—essentially, China’s most eligible bachelor.

Not everyone receives such a positive response from China’s netizens. In November 2009, pictures began to circulate online of a woman handing out flyers in Shanghai, seeking a tall, handsome and rich boyfriend with a Master’s in Economics, an international outlook, and who hadn’t fathered any children. The excessive demands, coupled with the woman’s less-than-supermodel appearance, led to much mockery online. Choice comments from one news report, translated by the website ChinaSMACK, included: “How about first going to get plastic surgery?” and “Even if I have to spend the rest of my life with just my left and right hands I would not want this kind of garbage.”

The woman, who had claimed to be working at a Fortune 500 company, was revealed to be Luo Yufeng (罗玉凤) a cashier at supermarket chain Carrefour (since Carrefour was 25th on the Fortune Global 500 list at the time, she was technically right). Web users quickly dubbed her Sister Feng (凤姐), or “Sister Phoenix”, but it wasn’t until she appeared on popular Jiangsu Province talk show Renjian in January 2010 that she really hit the big time.

Luo was joined on the show by two attractive young men, whom she claimed were her boyfriend and ex-boyfriend, and made a series of bold—some might say absurd—statements such as “No one in the last 300 years can compare with my IQ.” The boyfriends were later revealed to be actors, but both Luo and the TV station denied hiring them.

Whatever the truth, netizens were fascinated by the ongoing car-crash that was Sister Feng’s life. In March 2010 she announced that she would get plastic surgery, leading to a slew of cruelly photoshopped images; that September she released a near-nude photo series showing her, for reasons unknown, holding a stepladder. Meanwhile, she continued to make absurd pronouncements on Weibo while earning money with public appearances and TV guest spots, making boastful remarks to the jeers and humiliation of audiences—perhaps the nadir of which was an appearance on China’s Got Talent that saw her being hit with an egg.

But while “Sister Feng” was becoming China’s victim of choice, Luo Yufeng was quietly pocketing cash. As she told China Daily in 2010,“Making money is my priority now. I’ll do any TV show or commercial as long as I get paid for it.” She acquired a US visa, and that November she moved to New York. Barring her Weibo updates and a brief return to handing out leaflets (now in English, and advertising herself as “the hottest star in China”) in early 2012, she gradually faded from mainstream view, settling into her new role as a manicurist in The Big Apple. That, it seems, was what she had been trying to achieve all along.

Wang and Luo share a talent for skillful provocation, but their uses for this dubious gift show how much the landscape of Chinese social media is shaped by wealth and privilege. For Wang, whose comfort and security is guaranteed for the rest of his life, provoking ire and annoyance for the amusement of himself and his followers can be a hobby without consequence—even when the state press is baying for blood.

But for Luo, a plain, poor cashier in a society that has no time for those that are not beautiful, rich, or powerful, it was the only way to get ahead. Her canny grasp of the worst parts of human nature told her that if she acted boastful, arrogant, and condescending—in the way that Wang would later become famous for—audiences would be hungry for new opportunities to humiliate her, and that creating those opportunities would be a route to financial success.

As she said on Weibo in September last year: “I graduated from college and I was a cashier in Carrefour; I’m an ordinary common person, and the things that I said on television and to the public don’t fit my identity as a small person. But the same kind of talk coming from Wang Sicong’s mouth has a different outcome. The only difference between us is that he is the son of the richest man and I am from a farming family…”

And while their motivations and expectations are different, their insight into what makes web audiences tick are both fiercely on-point: they know we want to believe, because the fiction they’re selling is so much more interesting than the truth. Would Wang Sicong really tell Fan Bingbing she can’t act to her face? Probably not. Was Sister Feng really so stupid that she could unironically say, “Einstein is for sure not smarter than me. He invented light, right?” No.

But we want it to be true. We need it to be true, because the feeling of laughing along with the billionaire jester or jeering the woman who’s so stupid she doesn’t feel shame—and doing so alongside millions of others—feels so good.

- JAMES WILKINSON