PEKING OPERA MEETS WESTERN CLASSICS

2016-06-17ByJiJing

By+Ji+Jing

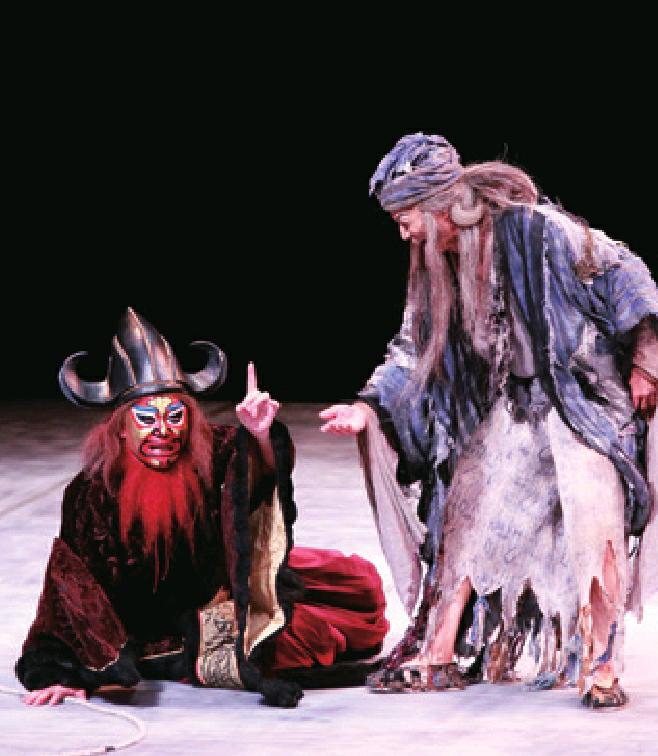

In a desolate wasteland, sits a small mound overhung with boughs. The stage is set for a Chinese version of Waiting for Godot, presented by the Contemporary Legend Theater from Taiwan at the Tianqiao Performing Arts Center in Beijing on May 15.

Waiting for Godot is a two-act absurdist play by Irish playwright Samuel Beckett that premiered in 1953. Originally written in French and translated into English by Beckett himself, it features two characters, Vladimir and Estragon, also called Didi and Gogo, who wait endlessly for the mysterious Godot, who never shows up.

The uniqueness of the Chinese version lies in its incorporation of Peking Opera elements into the Western classic. Didi and Gogo adopt Peking Opera performances, while the other three characters use modern performing styles. This innovative revamp amazed the audience.

Cui Hao, an undergraduate at Peking University who watched the performance, told Beijing Review that the play simultaneously took the form of Peking Opera while remaining loyal to the original plot. Cui is an avid fan of many genres of theater, from traditional Chinese operas to Western dramas. He saw King Lear staged by same troupe last year and was impressed by the intriguing fusion of Peking Opera with the Shakespearean play. This time around, innovations in Waiting for Godot excited him again.

The adaptation was created in 2005 by experimental actor, director and playwright Wu Hsing-kuo based in Taiwan. Wu said that he read at least six Chinese versions of the play to fully understand what it is about. “Waiting for Godot has inspired us to live life right here and now rather than waiting,” he told Beijing Review. Wu dedicated the performance to his mother, who moved to Taiwan from the Chinese mainland in 1949.

“In her later years, my mother would sit in the yard at dusk looking into the distance. She waited in vain to get back to her home on the mainland,” Wu told Beijing Review.

Waiting for Godot is one of the many Western classics Wu has transformed into Peking Opera. “Since there is no real plot development in the original play, I had less constraint in making adaptations and created some Chinese lyrics absent in the original version,” he explained.

Wus version of Greek tragedies such as Medea, Shakespearean plays such as Macbeth, King Lear, The Tempest and Hamlet, as well as The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka, have won accolades worldwide. His purpose behind the adaptations is to revive Peking Opera, which has been in decline on both sides of the Taiwan Straits.

Reviving tradition

In 1964, Wu was sent to the Taipei-based Fu Hsing Opera School (the predecessor of the Taiwan College of Performing Arts) to study Peking Opera at the age of 11. After eight years of study at the school, he enrolled at the Chinese Culture University, which exposed him to a number of Western plays vastly different from Peking Opera.

At 21, he joined the Cloud Gate Dance Theater in Taipei as a dancer. He was impressed by Western audiences enthusiasm for Chinese culture during the theaters tour of Europe and North America, which inspired him to embrace the concept of cross-culture art.

Concerned about the declining popularity of Peking Opera in Taiwan, Wu founded the Contemporary Legend Theater in 1986 and recruited over 20 young performers. “The Peking Opera community was idle and obsolete and lacked aspirations back then. I wanted to energize the atmosphere,” he said.

The first work produced by Wus theater was Kingdom of Desire, an adaptation of Othello combining elements of Peking Opera, hip hop, film, and modern dance. The rejigged play was set in Ji, a fictional ancient Chinese kingdom, instead of Venice. The blockbuster has been performed in more than 20 countries over the past 30 years and has won Wu international acclaim.

However, running a theater troupe was not easy, owing to the limited revenue generated from ticket sales. Wu had to use his own income from film acting to keep the theater afloat.

In 2001, another modern interpretation of a Shakespearean play, King Lear, was produced by Wus theater. He turned the performance into a mono act, playing a scarcely believable 10 roles all by himself, including Lear, his three daughters and the Fool. The roles were cast in four different types of Peking Opera characters—sheng (male), dan (female), jing (facepainted male) and chou (comic male).

“It was difficult for a mono act to present conflicts. From your performance, I saw your artistry as a performer,” said Eugenio Barba, artistic director and founder of Odin Teatret Denmark, in 2004. “Through this performance you overturned the tradition of Peking Opera, which also overturned the understanding of Shakespeare.”

This form was continued in the Peking Opera version of The Metamorphosis staged as the opening of the Edinburgh Art Festival in Britain in 2013, in which Wu played a marginally less demanding seven roles.

Controversies

However, Wus modernization of Peking Opera has sparked criticism from some. Critics say that he has tarnished the traditional Chinese art in a bid to appeal to Westerners through a clumsy fudge of Peking Opera and Western plays and doubt the sustainability of his work.

Nevertheless, Wu has not given up his quest to revitalize Peking Opera. “Traditional opera can survive only by evolving with the times,” said Wu, who remains dedicated to expanding theater. He added, “I want to build a bridge between the East and the West, and I wish Peking Opera could have a greater influence in the world, with its theories studied and discussed globally like we do with famous drama theorists Jerzy Grotowski and Constantin Stanislavski.”