PPARs介导脊髓损伤修复的研究进展*

2016-06-06林敬铨高梦丹张金一刘学红

林敬铨, 童 亮, 高梦丹, 张金一, 刘学红

(绍兴文理学院医学院,浙江 绍兴 312000)

PPARs介导脊髓损伤修复的研究进展*

林敬铨,童亮,高梦丹,张金一,刘学红△

(绍兴文理学院医学院,浙江 绍兴 312000)

脊髓损伤(spinal cord injury,SCI)是一种严重的神经系统功能障碍性疾病,能导致不同程度的感觉和运动功能障碍,主要包括原发性损伤和继发性损伤。原发性损伤是指在外力的直接作用下导致脊髓组织机械性的破坏,其伤害通常是不可逆的;继发性损伤是指在原发性损伤的基础上出现病理生理方面的改变从而造成损伤区域渐进性破坏,临床上主要针对继发性损伤采取相关治疗措施。目前导致继发性损伤机制主要包括炎症反应、自由基形成和脂质过氧化、局部血管功能紊乱、离子失衡、兴奋性谷氨酸中毒、细胞凋亡、轴突脱髓鞘、胶质瘢痕形成等[1]。过氧化物酶体增殖物激活受体(peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors,PPARs)是一类配体激活的转录因子,其活化后产生的抗炎、抗氧化、抑制线粒体功能紊乱等生物学效应在中枢神经系统退行性病变和急性损伤中起到关键作用[2],其表达程度的高低与SCI的预后关系密切,成为SCI治疗中的一个有效靶点。

1PPARs的分子结构与分布

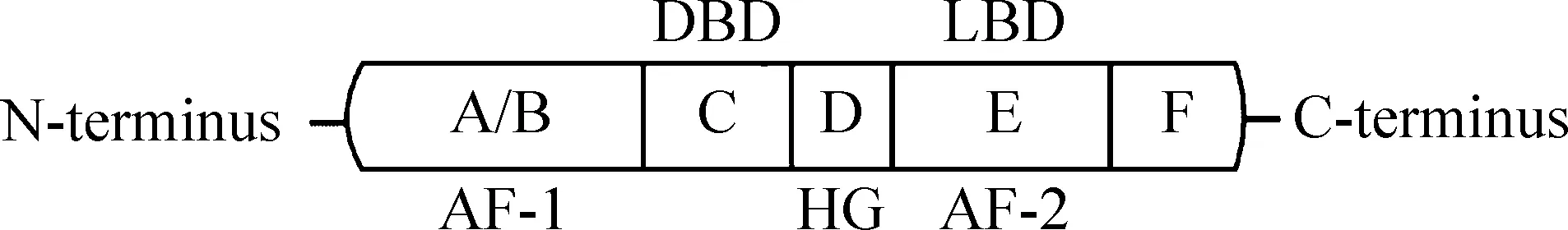

PPARs于1990年首次被Issemann 等[3]报道,属于核激素受体超家族成员之一,位于细胞核内,目前研究发现PPARs亚型有PPARα、PPARδ/β和PPARγ,其基因分别定位于人类的22、6和3号染色体上。 PPARs各亚型与其它核受体相似,由A~F六个主要的功能区组成。N端的A区和B区通常称为A/B区,是配体非依赖性的活性功能区(AF-1),不同亚型该区活性差异较大,其活性受磷酸化调节;C区是由2个锌指结构模序组成的DNA结合区(DNA-binding domain,DBD),由70个左右的氨基酸序列构成,具有高度保守性,能够和目标基因上的PPAR反应元件(peroxisome proliferator response element,PPRE)结合;D区为铰链区(hinge region,HG),连接C区和E区;E区属于配体结合区(ligand-binding domain, LBD),是配体依赖的活性功能区(AF-2),该区氨基酸序列的不同决定了各PPARs亚型对不同配体的亲和力;C端的F区功能目前并不是很明确[4],见图1。

PPARs在生物体内广泛分布,在肝脏、心脏、脾脏、肾脏、肌肉、脂肪组织等均有不同程度的分布[5]。在中枢神经系统,PPARα、δ/β和γ在脑和脊髓的不同区域表达程度各不相同,神经元和胶质细胞均能检测到PPARs的表达,PPARδ/β呈广泛性分布,而PPARα和PPARγ则表现为区域性分布[6]。

Figure 1.The structure of PPARs. A/B: ligand-independent activation function 1 (AF-1) domain; C: DNA-binding domain (DBD); D: hinge region (HG); E: ligand-binding domain (LBD) and ligand-dependent activation function 2 (AF-2) domain; F: function is not well understood.

图1PPARs结构示意图

2PPARs的配体及其神经保护作用

根据配体来源不同,PPARs的配体分为生理性(内源性)配体和人工合成配体。花生四烯酸的代谢衍生物8-羟基二十碳四烯酸(8S-HETE)和白三烯B4(LTB4)等是PPARα的生理性配体,PPARα的人工合成配体主要有贝特类药物(如非诺贝特、苯扎贝特、环丙贝特和吉非贝齐等)、Wy-14643、GW2331、GW7647等;PPARδ/β的生理性配体多数为不饱和脂肪酸如花生四烯酸、亚油酸和环前列腺素等,其人工合成配体主要有GW0742、GW501516、L165041和L-783483等;PPARγ能被脂肪酸及其衍生物(如二十二碳六烯酸、花生四烯酸和亚油酸等)、前列腺素衍生物(15d-PGJ2、PGA2和PGD2等)等生理性配体激活,其人工合成配体最为广泛应用的是用于治疗2型糖尿病的噻唑烷二酮类(thiazolidinediones,TZDs)药物(如罗格列酮、匹格列酮、环格列酮和曲格列酮等)[7-8]。

PPARs活化后能改善许多中枢神经退行性病变如阿尔茨海默病(Alzheimer disease,AD)、帕金森病(Parkinson disease, PD)、肌萎缩侧索硬化(amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ALS)和多发性硬化症(multiple sclerosis, MS)等,和中枢神经系统急性损伤如外伤性脑损伤(traumatic brain injury,TBI)和SCI等的病理过程,其机制主要涉以下几个方面:促进轴突再生;抑制线粒体功能紊乱;抑制Th1和Th17细胞的分化;促进少突胶质前体细胞(oligodendrocyte precursor cells,OPCs)的成熟分化;极化巨噬细胞,使之从炎性的M1细胞向抗炎的M2细胞转化[9]。

3PPARs配体调控的信号传导通路

3.1PPRE依赖性的转录激活/抑制这是最经典的PPARs的调节机制,当配体未与PPARs结合时,辅助抑制因子(corepressor,CoR)和组蛋白去乙酰化酶(histone deacetylases,HDACs)通过与PPARs结合抑制靶基因的转录;当配体进入细胞核内与PPARs分子上的E区结合后,使得PPARs的分子构象发生变化,导致其与辅助因子的结合能力发生改变,活化的PPARs与CoR和HDACs的亲和力下降,使之解离,同时激活的PPARs与类维生素X受体(retinoid X receptor,RXR)形成PPARs/RXR异源二聚体,该二聚体吸引辅助活化因子(coavtivator,CoA)与组蛋白乙酰转移酶(histone acetyl transferases,HAT),使得PPARs分子上的C区与目标基因启动子上的PPRE结合,启动目标基因的转录激活[10-11],见图2。

3.2PPRE非依赖性的抑制PPARs也可不与PPRE结合,而直接与靶蛋白结合,抑制该蛋白与其DNA反应元件的结合。PPARα能干扰平滑肌细胞中AP-1和NF-κB与其目标基因的结合,通过与p65和c-Jun蛋白的直接结合抑制血管的炎症反应[12]。PPARγ与p65/p50蛋白的结合抑制巨噬细胞在LPS刺激下IL-12的分泌,与NFAT的结合抑制IL-2和IL-12在激活的T淋巴细胞中的分泌,通过干扰c-Jun在T细胞中的激活而作用于IFN-γ基因的启动子[13-15]。

4PPARs与SCI

PPARs由于其在中枢神经系统的广泛分布,其介导的生物学功能在中枢神经系统疾病的病理过程中发挥着至关重要的作用[16-19],脊髓作为中枢神经系统的重要功能组成部分,PPARs在其损伤过程中的作用已成为目前神经科学领域研究的热点。研究表明,当SCI发生时应用PPARs各亚型相应的配体,配体可通过与组织细胞内PPARs的结合,激活其介导的信号传导通路,从而产生相应的生物学效应,对于SCI的病理以及病理生理过程具有一定的拮抗作用。PPARs各亚型与SCI的关系分述如下。

4.1PPARγ与SCIPPARγ是目前在SCI方面研究最多的PPARs亚型,PPARγ合成激动剂TZDs能防止SCI时的神经元损伤、运动功能失常、髓鞘丢失、神经病理性疼痛和炎症反应[20],PPARγ的生理性配体15-脱氧前列腺素J2(15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2,15d-PGJ2)和二十二碳六烯酸(docosahexaenoic acid,DHA)能减少SCI时脊髓炎症(iNOS、TNF-α、IL-1β)和组织损伤、中性粒细胞的组织渗入、NF-κB的激活和硝基酪氨酸的表达、细胞凋亡等[21-22],DHA还能改善体外培养的背根神经节细胞在过氧化氢刺激下的氧化应激反应。据报道,罗格列酮治疗的大鼠在SCI时能促进内源性神经前体细胞(neural progenitor cells,NPCs)的增殖,减少NF-κB的表达,但却未见明显的内源性NPCs分化为神经元[23]。匹格列酮能减少脊髓组织星形胶质细胞和NF-κB的激活,减少炎症介质TNF-α、IL-1β和IL-6的释放,通过PPARγ依赖和非依赖的机制改善神经病理性疼痛[24-25]。此外,雄激素睾酮单独或联合一种同化激素诺龙能抵抗SCI后引起的腓肠肌中PPARγ辅助活化因子PGC-1α表达水平的下降,并使得PGC-1α蛋白更易进入细胞核,改善大鼠SCI后后肢瘫痪肌肉的萎缩和肌纤维的能量代谢[26]。然而Yan等[27]发现SCI后骨骼中高表达的PPARγ可能通过RANKL/OPG信号轴使得骨质再吸收,同时还使得骨髓间充质干细胞更多地分化为脂肪细胞而不是成骨细胞,导致骨质的丢失,因此PPARγ激动剂是否有利于SCI的预后尚存在争议,见图2。

4.2PPARα与SCIPPARα在SCI后扮演了重要的角色,PPARα基因敲除小鼠相比正常小鼠SCI后,炎症反应和组织损伤更为严重[28]。小鼠SCI时,生理性PPARα配体十六酰胺乙醇(palmitoylethanolamide,PEA)激活PPARα产生的生物学效应与SCI时PPARγ的激活相似,亦能减少脊髓炎症和组织损伤、中性粒细胞渗入、硝基酪氨酸形成、iNOS和促炎因子的表达、NF-κB的激活、细胞凋亡等[29],进一步研究发现SCI后PEA的抗炎和神经保护作用不仅仅涉及PPARα,也与PPARγ和PPARδ/β有关[30]。血脑屏障(blood-brain barrier,BBB)与血脊髓屏障(blood-spinal cord barrier,BSCB)有着相似的组织结构,研究发现脑部的HIV感染将导致脑血管毒性、星形胶质细胞增生和神经元丢失,PPARα激动剂非诺贝特通过抑制ERK1/2和Akt信号通路,增加紧密连接蛋白claudin-5和ZO-1的表达水平,保护HIV-1特异的Tat蛋白诱导的BBB通透性改变,同时减少星形胶质细胞增生和神经元丢失[31]。然而Almad等[32]报道,PPARα合成激动剂吉非贝齐对小鼠SCI后的运动功能和组织病理没有改善作用。此外研究发现降血脂药物辛伐他汀在SCI中的抗炎作用也是由PPARα介导的[33],见图2。

Figure 2.Molecular mechanisms and biological effects of PPARs signaling pathway after SCI. (1): upon binding of a ligand to the PPARs, the receptors make a conformational change, CoR dissociation coincides with heterodimerization of the PPAR with the RXR, and transcriptional CoA is recruited along with HAT, which fires the transcription of target genes; (2): the biological effects of PPARγ activation; (3): the biological effects of PPARα activation; (4): the biological effects of PPARδ/β activation.

图2脊髓损伤后PPARs介导的生物学作用及其分子机制示意图

4.3PPARδ/β与SCIPPARδ/β广泛分布于脑和脊髓,能促进离体少突胶质细胞的分化和髓鞘的形成, PPARδ/β的mRNA和蛋白质水平在SCI后明显增加,在损伤区边缘出现大量的PPARδ/β+的新生少突胶质细胞[34]。PPARδ/β人工合成配体GWO742预处理能显著减少SCI体外模型时下游细胞和分子p38 MAPK、JNK/SAP激酶、NF-κB的激活、神经营养因子BDNF和DDNF的丢失、COX2的表达、细胞死亡等[35],此外GWO742还能增加糖尿病大鼠脊髓组织PPARδ/β的表达,延长糖尿病大鼠SCI后的生存时间[36]。替米沙坦能够减少脊髓组织炎症指标HMGB1和RAGE的表达,促进SCI后PPARδ/β和p-AMPK的表达,改善大鼠SCI后的运动功能和疼痛反应[37],见图2。

综上所述,在发生SCI时应用PPARα、δ/β和γ相应的配体,激活其介导的信号传导通路后,均能起到抗炎(特别是对下游分子NF-κB的抑制)和减少神经元的丢失作用。PPARγ的激活能促进NPCs增值,但却在一定程度上导致骨质的丢失;PPARα的激活能维持病理状态下BBB/BSCB的稳定性,但并非所有的PPARα激动剂均能改善SCI预后;PPARδ/β的激活对于糖尿病合并SCI的预后具有积极的意义。此外一些非PPARs配体药物也表现出PPARs依赖的药理作用,而其具体机制有待进一步阐明。

5问题与展望

PPARs活化后产生的抗炎和神经保护等多种生物学效应恰能针对SCI后继发性损伤中的多种病理生理改变起到一定的作用,然而由于PPARs在机体内分布广泛,导致其激动后定会产生相应的副作用。阐明SCI时PPARs基因的表达调控以及基因之间的相互作用关系,选择开发具有组织特异性的PPARs激动剂,减弱激动后产生相应的副作用,将是SCI后药物治疗的一个新途径。

[参考文献]

[1]Silva NA, Sousa N, Reis RL, et al. From basics to clinical: a comprehensive review on spinal cord injury[J]. Prog Neurobiol, 2014, 114: 25-57.

[2]Yonutas HM, Sullivan PG. Targeting PPAR isoforms following CNS injury[J]. Curr Drug Targets, 2013, 14(7): 733-742.

[3]Issemann I, Green S. Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proli-ferators[J]. Nature, 1990, 347(6294): 645-650.

[4]Owen GI, Zelent A. Origins and evolutionary diversification of the nuclear receptor superfamily[J]. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2000, 57(2): 809-827.

[5]Braissant O, Foufelle F, Scotto C, et al. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPAR-alpha, -beta, and-gamma in the adult rat[J]. Endocrinology, 1996, 137(1): 354-366.

[6]Moreno S, Farioli-Vecchioli S, Cerù MP. Immunolocalization of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and retinoid X receptors in the adult rat CNS[J]. Neuroscience, 2004, 123(1): 131-145.

[7]Wright MB, Bortolini M, Tadayyon M, et al. Minireview: Challenges and opportunities in development of PPAR agonists[J]. Mol Endocrinol, 2014, 28(11): 1756-1768.

[8]张秀红,宣姣,亓志刚. PPARα、 γ和δ:胰岛素抵抗治疗的靶点[J].中国生物化学与分子生物学报,2014,30(6):543-548.

[9]Mandrekar-Colucci S, Sauerbeck A, Popovich PG, et al. PPAR agonists as therapeutics for CNS trauma and neurological diseases[J]. ASN Neuro, 2013, 5(5): e00129.

[10]Gearing KL, Göttlicher M, Teboul M, et al. Interaction of the peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor and retinoid X receptor[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1993, 90(4): 1440-1444.

[11]McKenna NJ, O′Malley BW. Combinatorial control of gene expression by nuclear receptors and coregulators[J]. Cell, 2002, 108(4): 465-474.

[12]Ramanan S, Kooshki M, Zhao W, et al. PPARalpha ligands inhibit radiation-induced microglial inflammatory responses by negatively regulating NF-κB and AP-1 pathways[J]. Free Radic Biol Med, 2008, 15(12): 1695-1704.

[13]Alleva DG, Johnson EB, Lio FM, et al. Regulation of murine macrophage proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines by ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma: counter-regulatory activity by IFN-gamma[J]. J Leukoc Biol, 2002, 71(4): 677-685.

[14]Yang XY, Wang LH, Chen T, et al. Activation of human T lymphocytes is inhibited by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) agonists. PPARγ co-association with transcription factor NFAT[J]. J Biol Chem, 2000, 275(7): 4541-4544.

[15]Cunard R, Eto Y, Muljadi JT, et al. Repression of IFN-gamma expression by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma[J]. J Immunol, 2004, 172(12): 7530-7536.

[16]Carta AR, Simuni T. Thiazolidinediones under preclinical and early clinical development for the treatment of Parkinson′s disease[J]. Expert Opin Investig Drugs, 2015, 24(2): 219-227.

[17]Mattace Raso G, Russo R, Calignano A, et al. Palmitoylethanolamide in CNS health and disease[J]. Pharmacol Res, 2014, 86: 32-41.

[18]Yonutas HM, Sullivan PG. Targeting PPAR isoforms following CNS injury[J]. Curr Drug Targets, 2013, 14(7):733-742.

[19]Malm T, Mariani M, Donovan LJ, et al. Activation of PPARδ is neuroprotective in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer′s disease through inhibition of inflammation[J]. J Neuroinflammation, 2015, 12:7.

[20]Park SW, Yi JH, Miranpuri G, et al. Thiazolidinedione class of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists prevents neuronal damage, motor dysfunction, myelin loss, neuropathic pain, and inflammation after spinal cord injury in adult rats[J]. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2007, 320(3): 1002-1012.

[21]Genovese T, Esposito E, Mazzon E, et al. Effect of cyclopentanone prostaglandin 15-deoxy-Δ12,14PGJ2on early functional recovery from experimental spinal cord injury[J]. Shock, 2008, 30(2): 142-152.

[22]Paterniti I, Impellizzeri D, Di Paola R, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid attenuates the early inflammatory response following spinal cord injury in mice: in-vivo and in-vitro studies[J]. J Neuroinflammation, 2014, 11: 6.

[23]Meng QQ, Liang XJ, Wang P, et al. Rosiglitazone enhances the proliferation of neural progenitor cells and inhibits inflammation response after spinal cord injury[J]. Neurosci Lett, 2011, 503(3): 191-195.

[24]Griggs RB, Donahue RR, Morgenweck J,et al. Pioglitazone rapidly reduces neuropathic pain through astrocyte and nongenomic PPARγ mechanisms[J]. Pain, 2015, 156(3): 469-482.

[25]Jia HB, Wang XM, Qiu LL, et al. Spinal neuroimmune activation inhibited by repeated administration of pioglitazone in rats after L5 spinal nerve transection[J]. Neurosci Lett, 2013, 543: 130-135.

[26]Wu Y, Zhao J, Zhao W, et al. Nandrolone normalizes determinants of muscle mass and fiber type after spinal cord injury[J]. J Neurotrauma, 2012, 29(8): 1663-1675.

[27]Yan J, Li B, Chen JW, et al. Spinal cord injury causes bone loss through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ and Wnt signaling[J]. J Cell Mol Med, 2012, 16(12): 2968-2977.

[28]Genovese T, Mazzon E, Di Paola R, et al. Role of endo-genous ligands for the peroxisome proliferators activated receptors alpha in the secondary damage in experimental spinal cord trauma[J]. Exp Neurol, 2005, 194(1): 267-278.

[29]Genovese T, Esposito E, Mazzon E, et al. Effects of palmitoylethanolamide on signaling pathways implicated in the development of spinal cord injury[J]. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2008, 326(1): 12-23.

[30] Paterniti I, Impellizzeri D, Crupi R, et al. Molecular evidence for the involvement of PPAR-δ and PPAR-γ in anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective activities of palmitoyl-ethanolamide after spinal cord trauma[J]. J Neuroinflammation, 2013, 10:20.

[31]Huang W, Chen L, Zhang B, et al. PPAR agonist-mediated protection against HIV Tat-induced cerebrovascular toxicity is enhanced in MMP-9-deficient mice[J]. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2014, 34(4): 646-653.

[32]Almad A, Lash AT, Wei P, et al. The PPAR alpha agonist gemfibrozil is an ineffective treatment for spinal cord injured mice[J]. Exp Neurol, 2011, 232(2): 309-317.

[33]Esposito E, Rinaldi B, Mazzon E, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of simvastatin in an experimental model of spinal cord trauma: involvement of PPAR-α[J]. J Neuroinflammation, 2012, 9: 81.

[34]Almad A, McTigue DM. Chronic expression of PPAR-delta by oligodendrocyte lineage cells in the injured rat spinal cord[J]. J Comp Neurol, 2010, 518(6): 785-799.

[35]Esposito E, Paterniti I, Meli R, et al. GW0742, a high-affinity PPAR-δ agonist, mediates protection in an organotypic model of spinal cord damage[J]. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2012, 37(2): E73-E78.

[36]Tsai CC, Lee KS, Chen SH, et al. Decrease of PPARδ in type-1-like diabetic rat for higher mortality after spinal cord injury[J]. PPAR Res, 2014, 2014: 456386.

[37]Lin CM, Tsai JT, Chang CK, et al. Development of telmisartan in the therapy of spinal cord injury: pre-clinical study in rats[J]. Drug Des Devel Ther, 2015, 9: 4709-4717.

(责任编辑: 林白霜, 罗森)

[ABSTRACT]Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a devastating disease of the central nervous system. It elicits permanent neurological dysfunction. The neuroinflammation is a key point within the secondary damage in the locoal area of SCI. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), a group of ligand-activated transcription factors, play a critical role in the degenerative diseases in the central nervous system and acute traumatic injury because of their biological effects of anti-inflammation and neuroprotection when they are activated. This article reviews the signal transduction pathway mediated by PPARs and the progress of PPARs in the repair of SCI.

Progress of PPARs in repair of spinal cord injury

LIN Jing-quan, TONG Liang, GAO Meng-dan, ZHANG Jin-yi, LIU Xue-hong

(MedicalCollegeofShaoxingUniversity,Shaoxing312000,China.E-mail:liuxueh6588@126.com)

[关键词]过氧化物酶体增殖物激活受体; 脊髓损伤; 信号通路

[KEY WORDS]Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors; Spinal cord injury; Signaling pathway

[文章编号]1000- 4718(2016)05- 0956- 05

[收稿日期]2015- 12- 24[修回日期] 2016- 01- 27

*[基金项目]浙江省自然科学基金资助项目(No.LY15H170001)

通讯作者△Tel: 0575-88345099; E-mail: liuxueh6588@126.com

[中图分类号]R363

[文献标志码]A

doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000- 4718.2016.05.033

杂志网址: http://www.cjpp.net