China’s Climate Policy and Carbon Market Outlook in the Post-Paris Era

2016-05-12LiJunfengChaiQimin

Li Junfeng & Chai Qimin

China’s Climate Policy and Carbon Market Outlook in the Post-Paris Era

Li Junfeng & Chai Qimin

This research paper is the outcome of six authors: Li Junfeng, Chai Qimin, Ma Cuimei, Wang Jijie, Zhou Zeyu and Wang Tian. Li Junfeng is Director General/Professor, National Center for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation (NCSC); Chai Qimin is Deputy Director, Strategy and Planning Department, NCSC/Adjunct Professor, Research Center for Contemporary Management, Tsinghua University; Ma Cuimei, Wang Jijie, Zhou Zeyu and Wang Tian are Assistant Research Fellow, NCSC.

Acknowledgements: The National Science and Technology Program “The Key Supporting Research of The International Negotiations on Climate Change and the Domestic Emission Reduction (2012BAC20B04).”

T he Paris Agreement adopted by all parties at Paris Climate Conference (COP21) marks the beginning of new global cooperation efforts to address climate change. But as Chinese President Xi Jinping said, “The Paris Agreement is not an end, but a new starting point.”In the 23 years since the United Nations Environment and Development Conference in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1992, both China and the rest of the world have undergone profound changes. China’s climate change policies can be divided into three stages: the exploration period for institutional preparation from 1992 to 2008, the transition period for cultivation and strategic design from 2009 to 2015, and the breakthrough period for transformation and institutional innovation after 2015.

Exploration, Preparation and Institutionalization for China’s Climate Change Policy and Its Carbon Market

The Chinese government officially ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1993 and approved the Kyoto Protocol in 2002. As a non-Annex I country to the Convention, China has activelyparticipated in international negotiations, together with other developing countries, since the 1990s, urging developed countries to shoulder their historical responsibilities and fulfill their obligations by taking the lead in emissions reduction and providing financial, technology and capacity building support to developing countries. To tackle climate change, China takes the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol as the basic framework, takes multilateral negotiations under this framework as the main channel, and upholds the principles of equity, common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capacities, along with openness and transparency, extensive participation, partydriven process and consensus, and the overall consideration of mitigation, adaptation, financing and technology. Upon the initiation of the “Bali Road Map”in 2007, China strived to play a more active and constructive role in bilateral and multilateral dialogues and exchanges on climate change, and gradually linked international negotiations with its domestic actions.

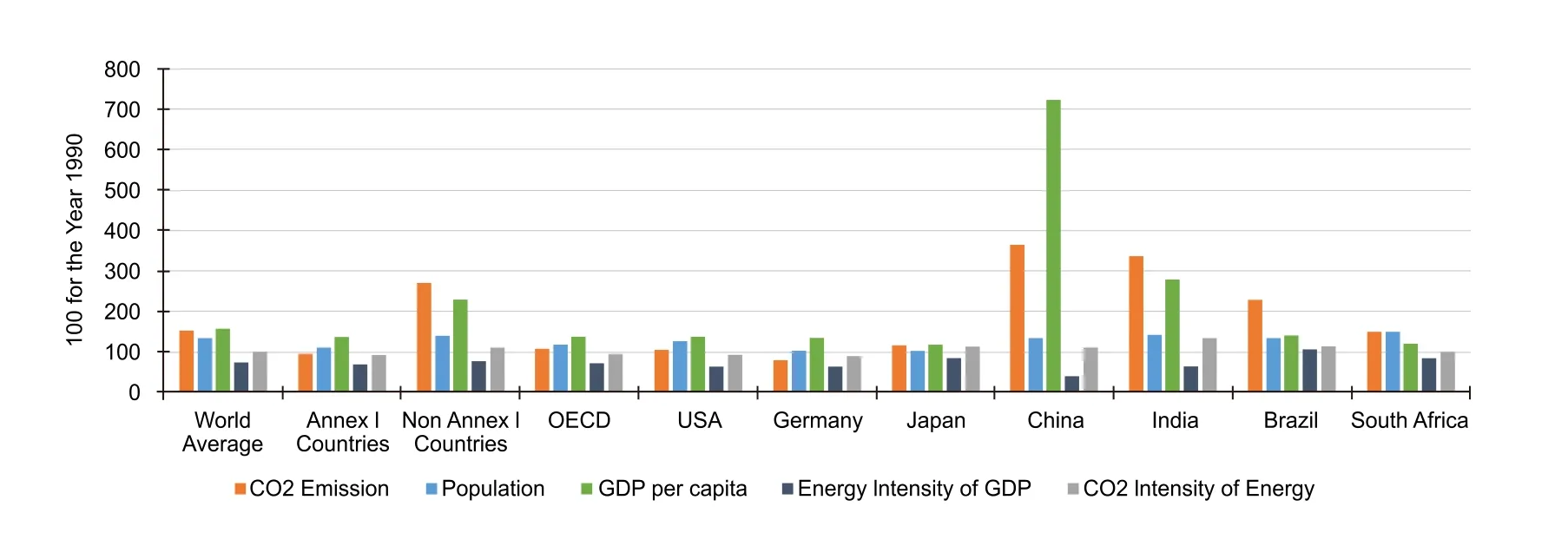

Fig.1 Comparison of Carbon Emission Drivers in Major Countries (KAYA)

During this period, China experienced its most rapid development, with its annual economic growth rate remaining around 10 percent. The modernization process driven by heavy industry made China the world’s biggest energy consumer and carbon emitter (as shown in Fig 1), putting heavy pressure on its environment. This prompted the concepts of scientificdevelopment and sustainable development to be proposed. In 2005, former President Hu Jintao emphasized improving the legal guarantees and strengthening policy conducive to protecting the environment, formulating a national plan for ecological protection, and raising awareness of the need to create an ecological civilization. At the end of 2005, the Decision of the State Council on Implementing the Scientific Outlook on Development to Strengthen Environmental Protection stated that China “should properly deal with the relationship between environmental protection and economic growth and social progress, preserve the environment in the course of development and promote development through environmental protection, and insist on economized, safe and clean development so as to achieve the sustained and scientific development”and under the guidance of the scientific outlook on development and relying on science and technology and innovating relevant mechanisms., it “should energetically develop environmental science and technology, and tackle environmental issues through technical innovations. We should establish an investment mechanism involving a diversity of major investors, including government, enterprises and social sectors as well as a mechanism for commercialized operation of some pollution treatment facilities. We should improve environmental protection systems and perfect a unified, coordinated and effective environmental regulation system.”In 2007, the Report to the 17th National Congress of the Communist Party of China clearly stated the new requirement of constructing an ecological civilization, and set the goal of “becoming a country with good ecological environment by 2020”as an important aspect of building a moderately prosperous society.

In 2007, the State Council set up a National Leading Group Dealing with Climate Change, Energy Conservation and Emissions Reduction (hereinafter referred as the Leading Group) to act as a deliberative and coordinating body in charge of climate change, energy conservation and emissions reduction, with the premier of the State Council as the head, the state councilor as the deputy head, and ministers and officials of each ministry as members. The Leading Group has set up a National LeadingOffice Dealing with Climate Change in the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) that is responsible for the daily work of the Group. The NDRC, which is responsible for managing and coordinating climate change work, set up the Department of Climate Change in 2008 to undertake concrete work assigned by the Leading Group. The Department of Climate Change makes comprehensive analyses of the impacts of climate change on economic and social development, and draws up strategies, plans and polices to address climate change. In the same year, China’s National Program to Address Climate Change was issued to ensure a systematic presentation of climate change policy. This set 2010 as the target year for reducing energy consumption per unit of GDP by approximately 20 percent the level of 2005 and mitigating carbon dioxide emissions correspondingly, and for striving to raise the proportion of the renewable energy exploitation volume (including large hydropower) in the primary energy supply to 10 percent, and make efforts to keep nitrous oxide emissions in the industrial production process no higher than the level of 2005, among other things.

The introduction of Measures for the Operation and Management of Clean Development Mechanism Projects (hereinafter referred to as the Measures for CDM projects) in 2004 and its implementation in 2005 marked the beginning of China’s participation in the global carbon market as a developing country. It became the world’s biggest supplier in 2008. The Clean Development Mechanism has been the main channel for China’s involvement in the international carbon emissions trading system and an important means to develop a carbon market governance model and evaluate the effects of carbon trading policies. In terms of the management framework, China has set up the CDM Project Review Council. In terms of CDM project application and implementation procedures, the Measures for CDM projects differentiates central enterprises and other project management agencies, specifies documents required for their application, and clarifies the processes for application, review, approval and registration.

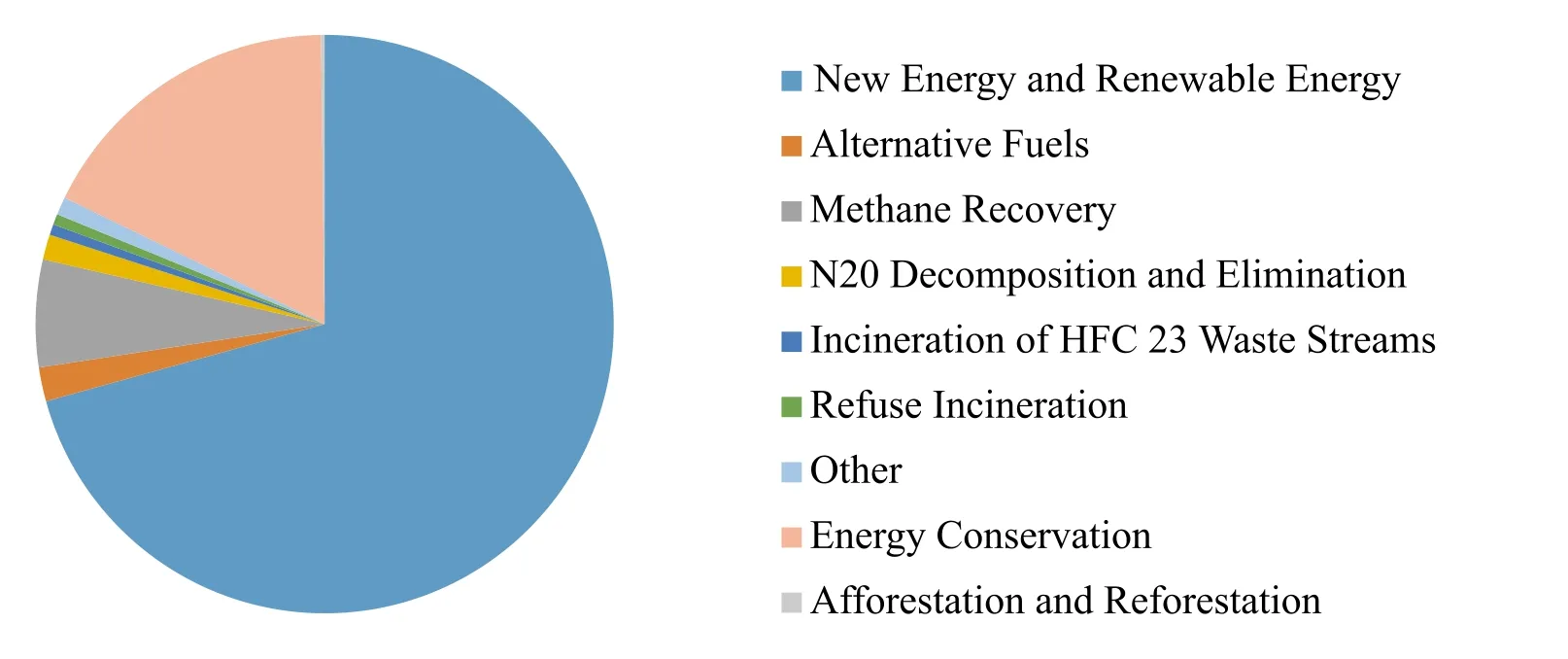

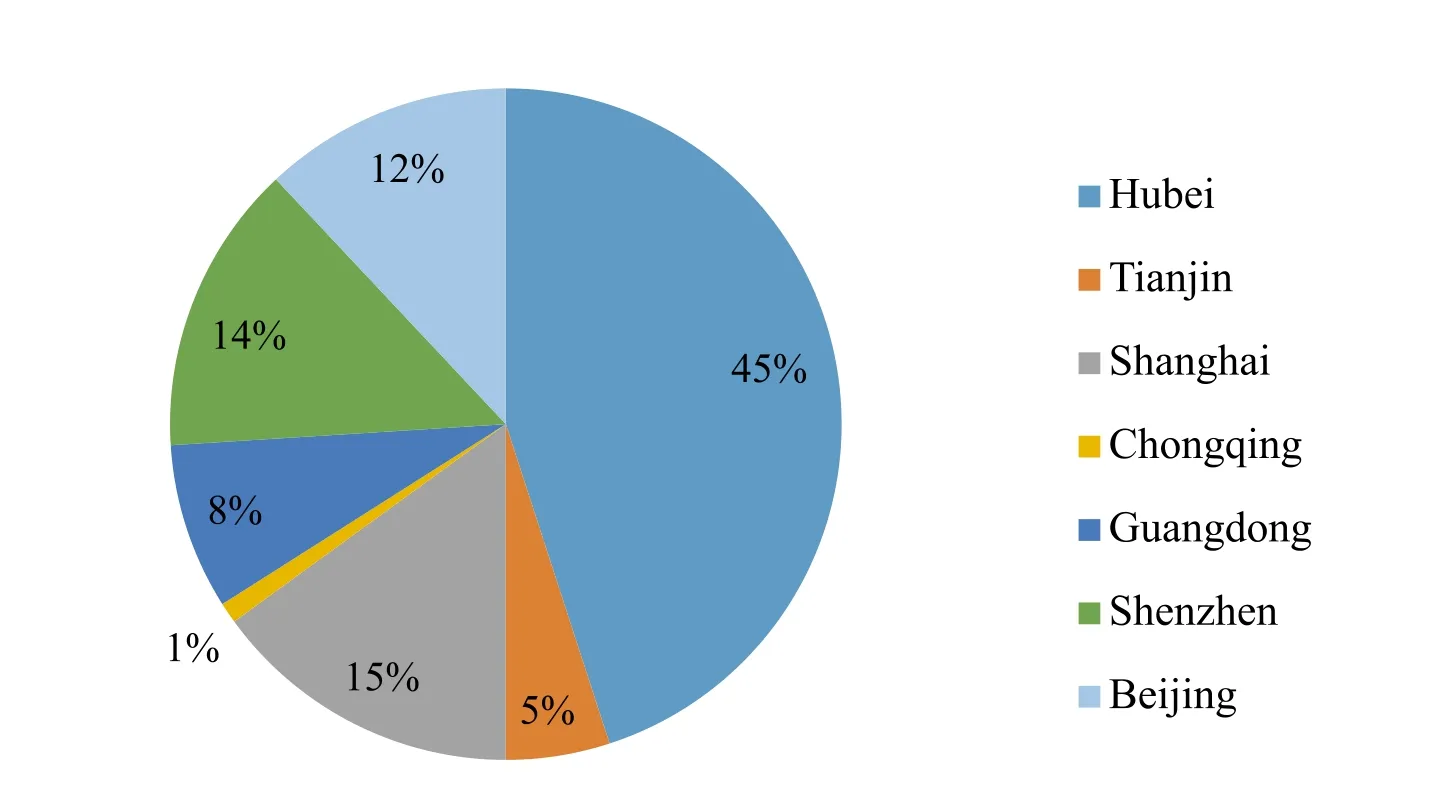

Fig.2 Proportion of CDM Projects of Various Types in China

By 2008, the NDRC had approved 1,795 CDM projects, whose carbon emissions reduction were approximately equivalent to 370 million tons of carbon dioxide on an annual basis. Described by project category, the largest percentage of CDM projects, up to 70.7 percent, were new energy and renewable energy projects, and a considerable portion of these were in energy conservation, energy efficiency improvement, and methane recycling projects, as shown in Fig. 2. Described by project distribution, approved CDM projects were mainly distributed in the central and western regions of China, with Sichuan and Yunnan provinces, and the Inner Mongolia autonomous region accounting for a large proportion. The rapid development of the domestic CDM market led to China’s good performance in the global carbon market. By 2008, the number of China’s CDM projects registered in the United Nation was 372, which accounted for about 28 percent of the world’s total.

Transition, Cultivation and Strategic Decision for Stimulating China’s Climate Change Policy and Carbon Market

In order to effectively control carbon dioxide emissions, China proposedcarbon emissions intensity reduction targets in 2009 for the first time, just before the climate conference in Copenhagen. It proposed that by 2020, its carbon dioxide emissions per unit of GDP would fall by 40-45 percent of 2005 levels. Despite the unsatisfactory outcome of the Copenhagen climate conference, China made its proposal with the upmost sincerity to promote the full, effective and sustained implementation of the Convention, and later actively participated in the negotiation process of the new Durban platform. Consolidating China’s position was the strategic support in the negotiations of “like-minded developing countries”; this effectively produced balanced international climate negotiations and safeguarded the legitimate interests of China and other developing countries. China also continued to strengthen and expand dialogue and cooperation on climate change with relevant countries and regions. To seek discourse power and a leadership role in the global climate governance, China held bilateral working group meetings with the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, South Korea and initiated framework agreements and cooperation projects, including the China-Australia Climate Change Ministerial Dialogue Joint Statement, the Memorandum of Understanding on the Promotion of Green Economic Cooperation between China and South Korea, the China-US Memorandum of Understanding on Strengthening Cooperation on Climate Change, among many others.

Since 2013, President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang have fully carried out new big power diplomacy and have issued several joint statements with other leaders that have far-reaching impacts. These include the China-US Joint Announcement on Climate Change, the China-India Joint Announcement on Climate Change, the China-US Joint Presidential Announcement of Climate Change, and the China-France Joint Presidential Announcement on Climate Change.

China’s economy entered a new normal in the 12th Five-Year Plan period (2011-15), and its economic structure and growth momentum are facing new challenges. At the same time, the contradiction between development and the environment has become increasingly prominent, asair pollution and other environmental issues have become more evident and pressing in recent years. Therefore, the building of an ecological civilization has been formally promoted as a need for the times. The 12th Five-Year Plan included the binding targets to be met by the 2015, including energy consumption per unit of GDP should be reduced by 16 percent, carbon dioxide emissions should be decreased by 17 percent, and the proportion of non-fossil fuel energy in the primary energy consumption should be 11.4 percent. The 12th Five-Year Plan for development of the coal industry set the target of controlling coal consumption below 3.9 billion tons by 2015. To provide development models and experience of low-carbon development with different characteristics, the government initiated low carbon pilot programs in provinces and cities. In July 2010 and November 2012, two batches of pilot national low carbon provinces (six in all) and low carbon cities (36 in total), were selected by the National Development and Reform Commission.

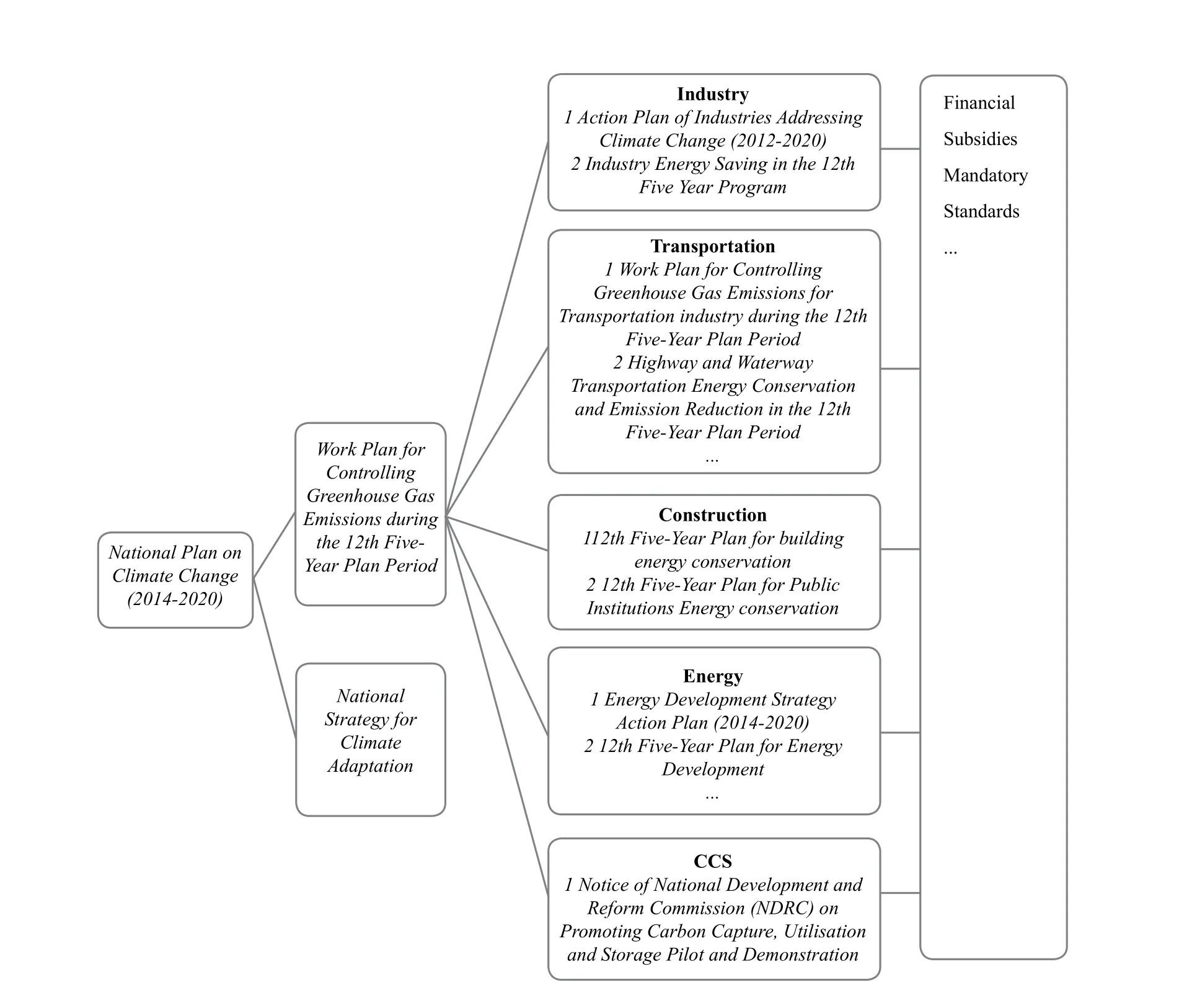

During the 12th Five-Year Plan period, the government promulgated a series of climate change policies, from macroscopic plans and strategies to specific policy tools, that gradually formed a relatively complete framework that can be divided into four levels, as shown in Fig.3: One, The National Plan on Climate Change (2014-2020) is China’s guiding policy response to climate change in the long term. The plan proposed targets in five areas including the control of greenhouse gas emissions, low carbon pilot demonstration, climate change adaptation, capacity building and international exchanges to be accomplished by 2020. Two, climate change mitigation efforts under the plan have specific objectives and the greenhouse gas emissions control program is coordinated with energy-saving and emissions reduction plans. Three, there are detailed objectives and key tasks for energy-saving and emissions reduction in the development plans for different sectors of the economy including energy, industry, construction, and transportation. Four, specific policy measures, such as financial subsidies and mandatory standards have been further promulgated to realize the planned objectives.

Fig. 3 China’s Planning System for Addressing Climate Change

The 12th Five-Year Plan and the 18th Third Plenary Session clearly proposed “gradually establishing a carbon emissions trading market”. In 2011, the National Development and Reform Commission approved seven provinces and cities, including Beijing and Shanghai, for pilot work on a carbon emissions trading market, and set 2013 to 2015 as the carbon trading pilot period. This move aimed to explore the carbon emissions trading system in line with China’s political and economic development needs, improve the carbon trading capacity of domestic enterprises, and lay thefoundation for the establishment of a national carbon market. As the leading authority for China’s carbon emission trading, the NDRC promulgated the Interim Measures for Carbon Emissions Trading Management, the Interim Measures for the Management of Voluntary Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction and Trading, verification guidelines and some other national level carbon trading policy documents, to guide and standardize the pilot work on carbon trading according to the national plan and policy requirements.

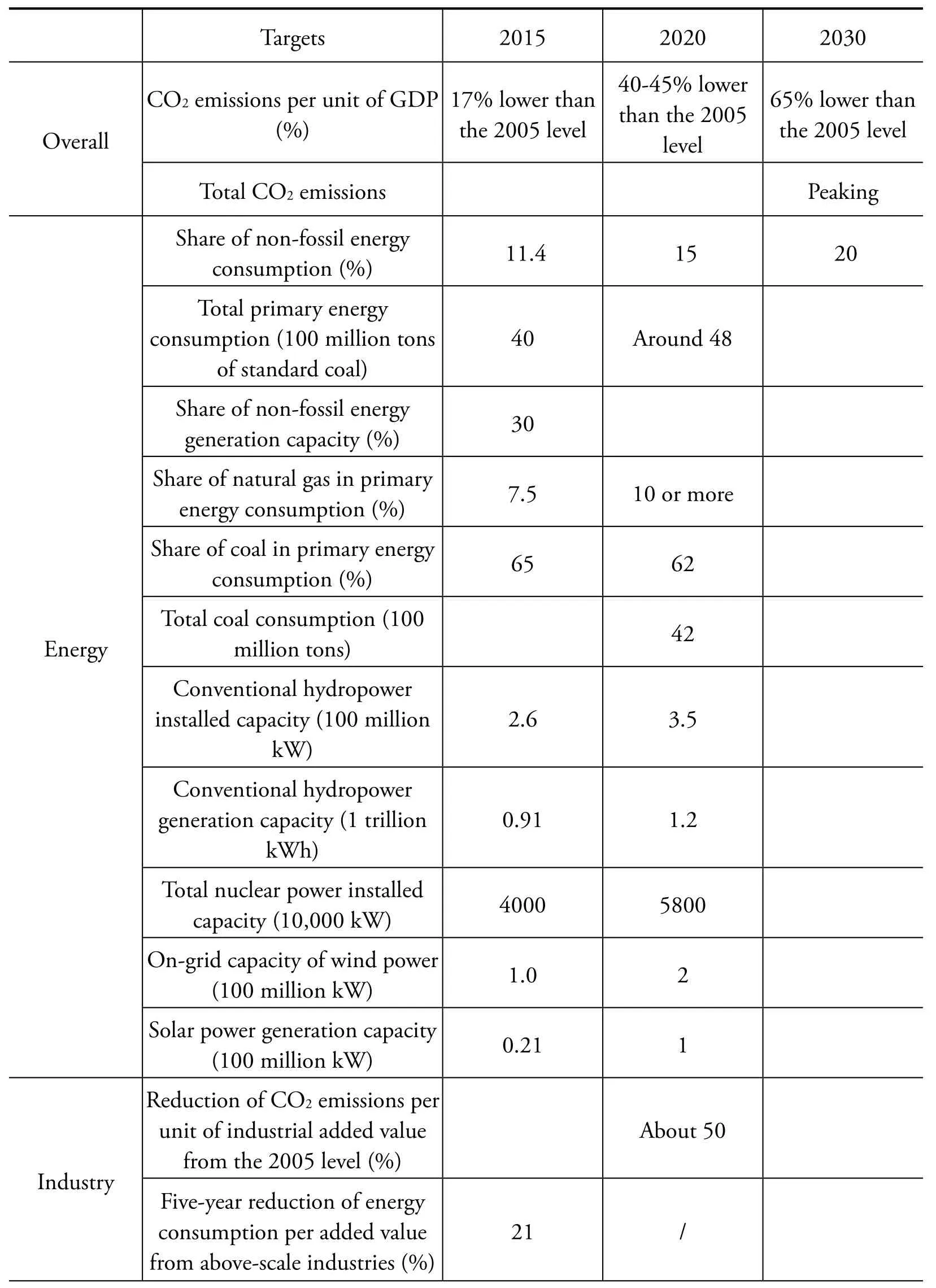

Fig. 4 Carbon Market Transaction Share for the Pilots

The pilot carbon markets in China have been running smoothly, and the scale of the trade has gradually expanded. For the purpose of centralized and unified management of carbon emissions trading, all the pilot areas set up carbon emissions exchange institutions as the designated places for carbon trading. The pilot quota and the national China Certificated Emission Reduction (CCER) is the main trading subject of the market at present. Because the introduction of CCER to the market came relatively late and the entry threshold is limited, the liquidity is relatively low and the transaction size is limited. As of Sept 30, 2015, the cumulative volume of the secondary market turnover of China’s carbon market was 44.613 million tons with a value of 1.30 billion yuan. The average transaction price is 34.3 yuan per ton(5.5 US$/ton). The market transactions in Hubei and Guangdong provinces and Beijing accounted for a relatively large proportion of the transactions. It is worth noticing that some pilot areas, including Guangdong, introduced a quota auction system besides free allocation, providing experience and lessons for building a more efficient carbon pricing mechanism.

In addition, the establishment and operation of the pilot carbon market promoted the development of the carbon finance business, reduced the financing difficulty of enterprises for energy saving and emissions reduction, and further met the diverse demands of carbon market participants. According to the design of traditional financial products such as credits, financial institutions including banks and securities firms launched a series of carbon financial products based on emissions quotas and CCER, such as carbon pledges, carbon mortgages, carbon bonds, carbon funds, carbon repurchases, etc. The majority of financial institutions started carbon finance businesses in carbon trading pilot areas with higher activity, such as Hubei province, Beijing and Shanghai, and generally choose the higher credit rating companies or CCER project owners as partners. The amount of the contracts varied from millions to hundreds of millions yuan.

Breakthrough, Transformation and Innovation for China’s Climate Change Policy and Carbon Market

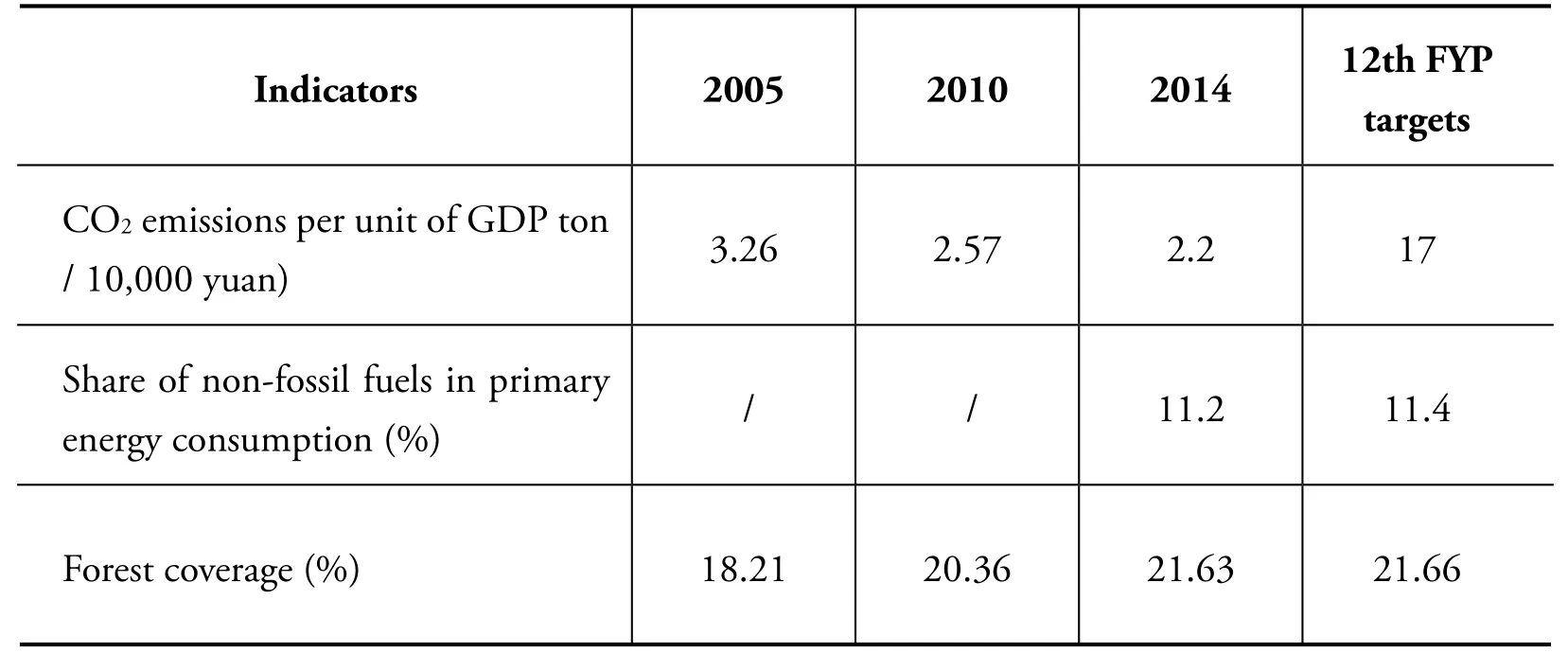

China has played an important role in achieving the Paris Agreement, fully expressing its views and having them accepted and become more actively involved in the global climate governance process. Overall, China’s climate change policy in the previous two stages was highly effective in general based on its national conditions, development stage and actual capabilities. In 2014, the carbon dioxide emissions per unit of GDP were cut by 33.8 percent from the 2005 level, faster than the progress (30.1 percent) towards the target of “emission intensity reduction of 45 percent by 2020, and cut by 15.8 percent from the 2010 level,”ahead of the schedule set out in the 12th Five-Year Plan. In terms of non-fossil fuel energy, the installed capacity increased 1.6 times, from 52,000 kW to 136,000 kW from 2005 to 2014, and its share in the total installed capacity grew from 23 percent to 33.6 percent, higher than the target of 30 percent put forward in the 12th Five-Year Plan for Energy Development. By the end of 2014, China’s non-fossil energy generation capacity stood at 1.4 trillion kWh, equivalent to 25.6 percent of the national total, higher than the target of 20 percent set for 2015. In addition, forest coverage in 2014 was very close to the target set for 2015.

Table 1 China’s climate change targets and progress of completion

It should be noted that China has made only a small step forward in its low-carbon transition. Although remarkable results have been achieved, the situation remains grim and greater courage and determination are needed to push forward reform. First, although the institutional system and working mechanism have been improved, the legislative progress on important systems is slow and the input of public resources far from adequate. National legislation on climate change and low-carbon development has not been put on the agenda. The current regulations, standards and rules provide limited means, leading to serious work overlap and fuzzy boundaries thatundermine the proactive response to climate change. Public finance also fails to effectively support energy conservation, emissions reduction and low carbon development, due to the absence of reasonable and balanced allocation mechanisms for property rights and administrative powers, giving rise to fierce competition for financial resources. Second, the positive results in the control of greenhouse gas emissions can largely be attributed to the economic downturn. The base of low-carbon industries remains relatively weak. The exploration of a low-carbon industrial development pattern is limited to simple scale expansion and redundant construction of a few new energy industries, while little technological advances and business model innovations have been realized. The low-carbon economy is certainly not yet strong enough to support a full-range low-carbon economic transition. Effective incentive policies are expected to attract broad participation of social capital in low-carbon development. Third, the low-carbon pilots have progressed, but the output and energy consumption of high-carbon industries continue to expand. Even after several years of communication and promotion, a number of sectors, regions and officials are still not fully aware of the strategic significance of and urgency for climate efforts and lack the initiative to face up to the issue, due to the deep-rooted traditional thinking and misunderstanding that low-carbon development impedes economic growth. Effective transmission of the pressure of responsibility has not been established, and objectives have not been appropriately set out and implemented at the regional level. Industries with intensive energy consumption and high emissions remain the focus of the industrial layout by local governments. The six high-energy industries exhibit growth faster than the average national economic growth. Specifically, crude steel production surpassed 800 million tons and steel 1.1 billion tons; cement production is approaching 2.5 billion tons and coal consumption exceeds 4 billion tons. Meanwhile, industrial restructuring continues to encounter great resistance. Although the pilot areas have proposed emissions reduction targets, the deadlines for peaking emissions are incompatible with the requirements of shareholders and they lag behind expectations.

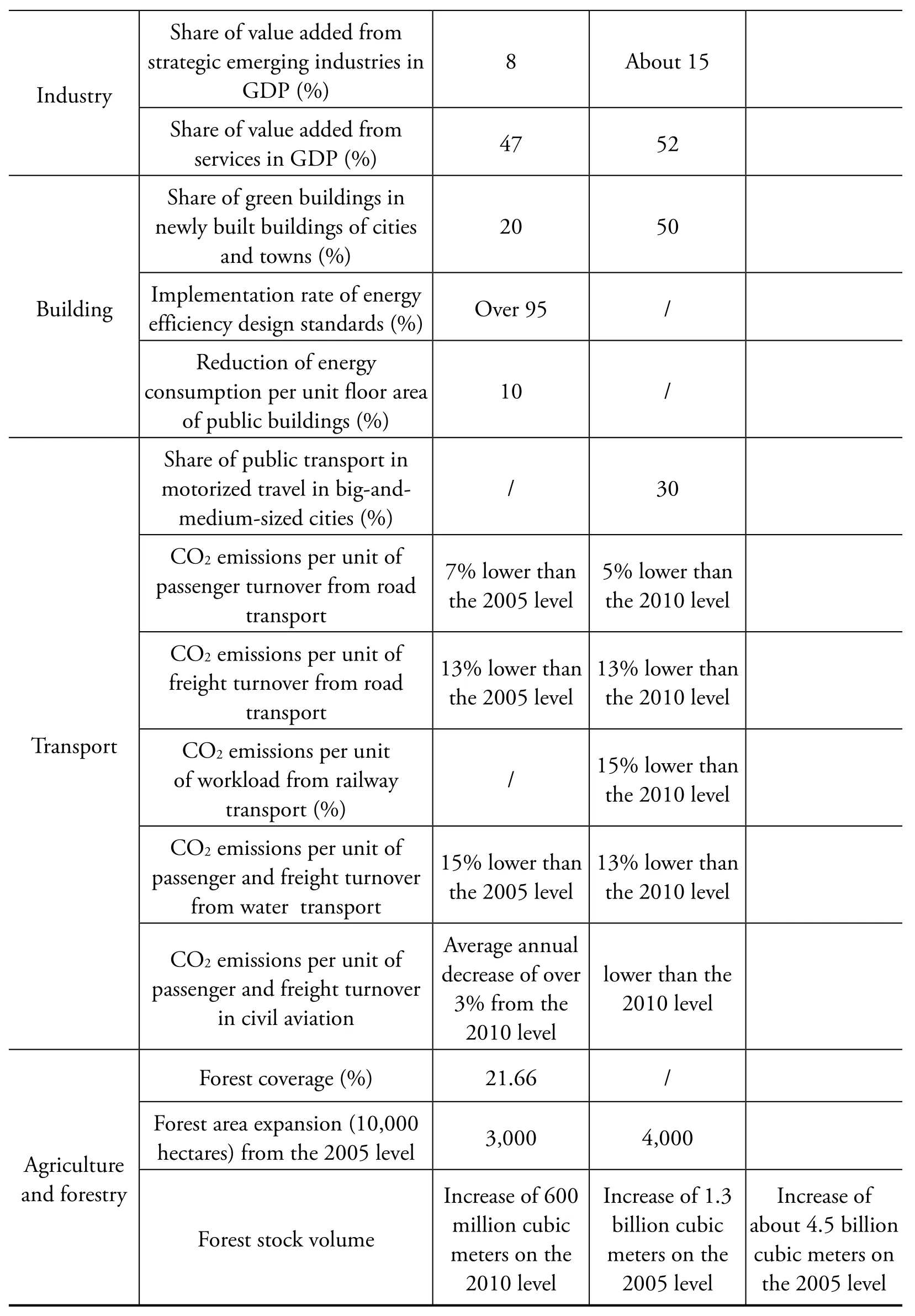

In a meeting with the US secretary of state in 2014, President Xi Jinping clearly pointed out that addressing climate change is what China needs to do to achieve sustainable development, as well as to fulfill its due international obligation as a responsible major country. “This is not the request of others but on our own initiative,”he said. At the Summer Davos Forum the same year, Premier Li Keqiang stressed: “We have the resolve, the will and the capability to pursue green, recyclable and low-carbon development. China will work with other countries to effectively address global climate change.”Vice-Premier Zhang Gaoli said at the UN Climate Summit that “China will make greater effort to effectively address climate change and take on international responsibilities that are commensurate with its national conditions, stage of development and actual capabilities.”Before the Paris Climate Change Conference, the Chinese government submitted the Enhanced Actions on Climate Change: China’s Intended Nationally Determined Contributions to the Secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). As shown in Table 2, China has nationally determined its actions by 2030, These are: 1) to achieve the peaking of CO2emissions around 2030 and make best efforts to peak early; 2) to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 20 percent; 3) to lower CO2emissions per unit of GDP by 60-65 percent from the 2005 level; and 4) to increase its forest volume by around 4.5 billion cubic meters on the 2005 level. By 2014, the energy consumption per unit of GDP was 29.9 percent lower than the 2005 level and CO2emissions were 33.8 percent lower than the 2005 level.

China has been active in promoting the transition to a low-carbon economy, driven by both domestic needs and international responsibility and has become the world’s largest country in terms of energy conservation and utilization of new energy and renewable energy. It also vigorously supports other developing countries responses to climate change through South-South cooperation. Meanwhile, as the world’s biggest emitter, China is subject to doubts about its efforts and its elevated status in the global governance order has aroused the vigilance of the traditional powers.

Table 2 China’s nationally determined action objectives

Data sources: National Plan on Climate Change (2014-2020), 12th Five-Year Plan for Energy Development (SC [2013] No.2), Energy Development Strategy Action Plan (2014-2020) (SC [2014] No. 31), 12th Five-Year Plan for Industrial Energy Efficiency (2012), Action Plan for Addressing Climate Change in Industry (2012-2020) (MIIT [2012] No. 621), 12th Five-Year Plan for Building Energy Efficiency (MOHURD [2012] No. 72), 12th Five-Year Plan for Energy Efficiency of Public Institutions (NGOA [2011] No. 433), Work Program for the Control of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Transport During the 12th FYP Period (MOT [212] No. 419), 12th Five-Year Plan for Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction in Road and Water Transport (MOT [2011] No. 315), Opinions on the Implementation of the Comprehensive Work Plan of the State Council on Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction During the 12th Five-Year Plan Period in Road and Water Transport (MOT [2011] No. 636), Action Points for China’s Forestry Departments in Response to Climate Change During the12th Five Year Plan (MOF [2011] No. 241), 12th Five-Year Plan for Civil Aviation Development, and Enhanced Actions on Climate Change: Intended Nationally Determined Contributions.

China is currently in a critical, historic period of development. By 2020, China will basically complete its industrialization and transform into a moderately prosperous society, according to the design of its Two Centenary Goals, and by 2050, into a modern country (reaching the level of moderately developed countries). Over a longer timeframe, China will face difficulties and challenges in the process of simultaneously dealing with slower economic growth, making difficult structural adjustments, and absorbing the effects of its previous economic stimulus policies. Nevertheless, China is still determined to peak its emissions around 2030. Xi stressed in his speech at the Opening Ceremony of the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC in Paris that countries should join hands and contribute to establishing a fair and effective global system to tackle climate change, achieve higher-level sustainable development worldwide and build international relations of winwin cooperation.

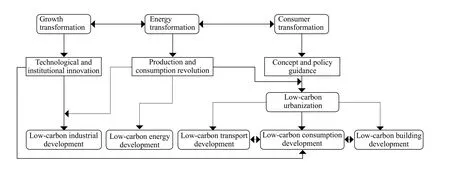

The overall goal and idea of China’s climate change policy is to decarbonize its economic and social development through the establishment of an operable enforced mechanism for peaking emissions early, with consideration given to the transformation of the growth model and optimization of its energy structure. By means of comprehensive promotion and classification guidance, the eastern region is expected to peak emissions early, leaving space for development of the western region; industrial sector is expected to peak emissions early, leaving space for the development of other sectors; emissions from coal, oil and other high-carbon energy sources are expected to peak early, leaving space for natural gas and non-fossil energydevelopment. Specifically, the country’s decarbonization will involve the low-carbon transformation of economic growth through technological and institutional innovation, low-carbon transformation of the energy system through energy production and consumption revolution, and low-carbon transformation of consumption patterns through conceptual change and policy incentives, as shown in Figure 5. The ultimate goal of climate change policy is to pursue green, low-carbon, climate-adapted and sustainable economic and social development. In the next phase, China should focus its efforts on three transformations, as follows:

1) Low-carbon transformation of the growth mode. Only by accelerating transformation of its growth mode by taking advantage of technologies and institutions that match the new constraints on resources can new economic growth points be created and the growth mode upgraded to constantly improve the quality and efficiency of China’s economic development.

2) Low-carbon transformation of the energy system. Huge energy consumption and the high carbon energy mix have put increasingly acute pressure on the environment and created complex environmental problems. This calls for a revolution in the country’s energy consumption, energy supply, energy technology and energy system, encouraging and nurturing green, low-carbon innovations in technologies, industries, and business models. Such a revolution will make it possible for China to gradually shake off its high dependence on fossil fuels in the process of economic development and rely on low-carbon or even carbon-free energy sources at the end of this century.

3) Low-carbon transformation of consumption patterns. Green consumption and green services consumption should be encouraged to foster low-carbon intensive, sustainable consumption patterns. Robust systems for infrastructure, products and public services should be put in place in order to provide a variety of low-carbon products and services, including clothing, food, housing, transportation and daily necessities. A price system that reflects environmental costs should be established to optimize theinvestment and trade structure, create a sound carbon consumption market, and ultimately stimulate new endogenous growth points for the Chinese economy.

Fig. 5 Connotation of addressing climate change and the three transformations

Globally, low-carbon development has become a strategic choice for most countries. In line with the global trend of development and transformation, China chooses low-carbon development as an important instrument to promote its economic and social transformation and optimize its energy mix. Low-carbon development is also required to achieve the strategic objectives of building a moderately prosperous society and a modern country. Through appropriate efforts, China is likely to peak emissions earlier and at lower levels than developed countries, opening up a new path for low-carbon development in developing countries while contributing to global climate change mitigation. It can be foreseen that the low-carbon transformation of its growth mode, energy system and consumption patterns will bring about a new technological and industrial revolution and create new economic growth points, expanded market capacities and increased employment opportunities. We need to build consensus and take actions to foster a mode of development towards win-win cooperation and shared economic and social benefits of the green, low-carbon transition.

According to the State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2015 of theWorld Bank, since January 2012, the number of carbon pricing instruments already implemented or scheduled for implementation has almost doubled. Currently, about 40 national jurisdictions and over 20 cities, states, and regions, including six countries and over 10 cities in Asia, are putting a price on carbon. It is estimated that in 2020, the value of the global carbon market will reach 3.5 trillion US dollars and surpass the oil market to become the world’s largest market. Xi mentioned in the China-US Joint Presidential Announcement on Climate Change that “China plans to launch in 2017 its national emissions trading system, covering key industry sectors such as iron and steel, power generation, chemicals, building materials, paper-making, and non-ferrous metals.”By then, China will replace the European Union as the world’s largest carbon market. The emissions trading system is expected to lead to ecological governance that gives full play to the role of market in effectively allocating green resources, mobilizing green value and reducing environmental costs.

The Paris Agreement requires parties to adhere to national determined contributions, with the progress assessed through a global stocktaking process. The nationally determined mitigation and adaptation actions of parties aim to keep the global temperature rise below 2 degrees (and pursue more efforts to achieve 1.5 degrees) and achieve the long-term aim of achieving a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century. This new climate regime will produce a global trend for low-carbon development and form new competition mechanisms and rules, so that low-carbon development is integrated not only as the requirements and commitments of international climate agreements, but also as determined behavior to enhance the competitiveness for sustainable development. Low-carbon development turns burdens and challenges into opportunities. China will certainly play an increasingly important role in promoting this trend.

杂志排行

China International Studies的其它文章

- The Belt and Road Initiative in Global Perspectives

- The Belt and Road Initiative Results from the Advancing of Our Times

- Characteristics and Trends of the ‘New Normal’ in China-US Relations

- Russia’s Middle East Strategy: Features, Background and Prospects

- New Trends in US Asia-Pacific Alliance Relations

- Japan’s Meddling in the South China Sea: Current Movements and Future Developments