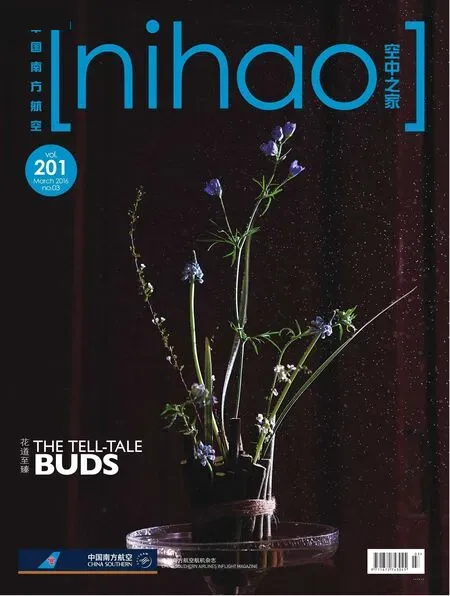

A BlT OF CHlNESE ART OF FLOWER

2016-04-14TextByTianJiwei

Text By Tian Jiwei

Photos Provided by the Flower Arrangment Museum of China Translation by Shi Yu

A BlT OF CHlNESE ART OF FLOWER

一幕花道

Text By Tian Jiwei

Photos Provided by the Flower Arrangment Museum of China Translation by Shi Yu

本文參考自黄永川的《中國插花史研究》

The word “fl ower” was defi ned by Xu Shen, a Chinese philologist in the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD), in his ShuowenJiezi, the fi rst Chinese dictionary with character analysis, as being numerou and grand. Ancient Chinese tended to use words as information carriers. Therefore, only by starting from the beginning and following the time line can we get the right idea of hua, i.e. flower.

The Northern Wei Dynasty (386-557 AD) agriculturist JiaSixie wrote in QiminYaoshu, literally: “essential techniques for the welfare of the people”, that“flower and grass are just for the pleasure of the eye. Blooming, yet fruitless. But if so, then what is the meaning of them?” JiaSixie was convinced that flowers were too useless to be listed in the book of agriculture.

Since then, flowers and grass were excluded from agricultural literatures. They were catergorised into encyclopedias along with other flora and fauna, or instruments. Belittled, the science of the flower was not systemically concluded or illustrated, leaving tons of diffi culties for Chinese descendants to learn or study. The research of fl wers and grasses thus remained vague for a long time.

With no choice at hand, people who were interested in this subject could only graft their experience and feelings of flower appreciation onto "social science", and let it be known. Accordingly, a man-made standard had been brought up for the appreciation, and this is where the Chinese art of flower originated.

When it came to the Song Dynasty (690-1279), Chinese art of flower reached its peak. Given stable political situation and well-off civil life, people with refi ned tastes developed a number of recreational activities, including Chahua, i.e. flower arranging in vases. As a good way to decorate, Chahua prevailed. From the palace to ordinary residences, from temples to casinos, it could be seen everywhere.

Ouyang Xiu, famous statesman, essayist and poet in the Song Dynasty, wrote in an essay that in the City of Luoyang, people, rich or poor, noble or vulgar, would gather a massive number of flowers in spring just for decoration. In 1104, a scholar named Liu Meng listed 163 kinds of chrysanthemum in a book, from which we can see how various kinds of flowers were in the Song Dynasty.

Lu You, legendary poet in the Southern Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD), often got fresh flowers from a farmer on his way back home everyday. In return, Lu You paid tribute to the farmer by composing poems for him, creating many fl ower-themed poems that kept shining for thousands of years.

Besides poems, among those Song Dynasty pottery tomb fi gures unearthed in Henan Province, there were also many unearthedfemale fi gures holding vases with flowers in, which reveals how prevailing flower arranging was in Central China at the time. There was a kind of performance in the palace where a giant vase was set in the middle of the stage, and the dancers were supposed to pick flowers out of the vase.

A Confucian school of idealist philosophy was widely adopted in the Song Dynasty. To ease the pressure from society, some people started to resort to Buddhism and Taoism, longing for detachment from the mainstream. They bonded their feelings to the flowers and secluded themselves into the woods, as a way to express their respect to the heaven, the earth, and all walks of life within the Universe.

Painting techniques and styles also left great infl uence on the art of flower arrangement in the Song Dynasty. The idea of fl ower arrangement has gone from realistic arranging to freehand arranging centering on spatial and spiritual expression. This change has given the art of flower a brand new value. Literati had been particularly fond of this kind of spiritual expression conveyed by flowers. For example, it was once a fashion for the people to write essays about lotuses, which were attached with an image of rectitude and purity, as they observed that the lotuses rise up from the mud without being stained.

Literati in the Song Dynasty created four forms of arts, namely, incense burning, tea making, painting hanging and flower arranging. Even the government had set specialiseddepartments for these four art forms. The one responsible for flower arranging is called PanbanJu, meaning the Department of Decoration. Since the four forms of arts had become offi cial, they had been gradually accepted by society as a new norm of fashion. Frankly speaking, a man without the ability to perform any of the four forms of arts could not fi nd his place in society back then.

Flowers were personified by literati in the Song Dynasty. People put personal preferences, even some rather subjective ideas, into their idea of what different kinds of flowers stood for.

Plum blossom, orchids, bamboo and chrysanthemum were described as the "four gentlemen", and other plants such as narcissusesand pines also had their own "personalities". For instance, plum blossoms are deemed to be proud; bamboos are modest and morally upright; chrysanthemums are clear and clean; and orchids are thought to be open-minded. In other words, flowers become carriers of what literati longed for.

However, there are also some other people who fancy a certain type of abnormal arrangement of flowers. Some used a single bud held by a withered rod to express loneliness; some used a cluster of red flowers with one green leaf in the middle to create a beauty of pain. The unique taste of those literati upgraded the appreciation level of the time. Although some tastes may seem unacceptable, the idea of spiritual expression thrived. With such an idea, the Song Dynasty had left us a sea of phenomenal heritage.

"Flower utensils" were made just for flower arrangement. Made in several major kilns in the Song Dynasty, they are simply and plainly patterned in order to highlight the beauty of the flowers in them.

For better arrangement, the Song people even developed a kind of "multi-hole vase". There were vases with 7 holes, 9 holes, 16 holes and 31 holes respectively. Additionally, in order to prevent the flowers from the cold air in winter, people added tin inner containers or tubes into the utensils for flower arrangement.

Ancient Chinese has accumulated profound knowledge and experience in terms of flower cutting, nurturing, arranging and appreciating. They were all incredible skills. Even the Japanese art of flower arrangement, ikebana, absorbed ideas and experience from China. We can undoubtedly feel the joys the Song people had by seeing how much the Japanese love chrysanthemums and plum blossom.

东汉(公元25—220年)许慎的《说文解字》是这么定义“花”的:“华”即是“花”,有繁多盛大的意思。中国古代以文字作为信息的载体。

加之,北魏时期(公元386—557年)的农学家贾思勰在《齐民要术》中记载道:“花草之流,可以悦目。徒有春花,而无秋实。匹诸浮伪,盖不足存。”他认为,花卉知识不入流,花不能温饱,要它何用?自那以后,历代农学家不再把花草之流纳入农学专著中,而是将其和动植物、器物等统归至“谱录”之中。因此,在当时这种贬低意识的作用下,花卉及其涉及的自然科学没能得到系统的归纳论述,这不免导致后人难以系统地学习研究。

宋代时期(690—1279年),中国花道迎来了它的鼎盛巅峰。当时国家政局稳定,百姓生活安康,文人雅士发明了很多的生活情趣,而插花就是其一。不管是广宫廷、官府、佛寺、道观,还是茶寮、酒楼、赌坊、人家,插花都随处可见。

文人欧阳修在《洛阳牡丹记》中记录道,洛阳城中无论贵贱贫富,都会在春季使用大量的装饰花。1104年,学者刘蒙在《菊谱》中录菊163个品种,可见宋代花类繁多。

除了流传下来的诗歌以外,河南出土的宋代陶俑中,也发现了众多女性手捧花瓶的俑像——这揭示了中原地区插花活动的盛行。

但说宋代理学大行其道,唯官尚儒。因此,为了缓解社会压力带来的不适,人们开始向佛、道求解,向往世外的解脱,寄情花草,隐居山林,以此来表达对道德天地和花草乾坤的崇尚。

由于宋代流行写意山水画,工笔花鸟画的艺术成就也转而影响了插花艺术。当代创作范畴由写实技法慢慢演变至对写意空间的勾勒。这种技法赋予了花道一种独有的价值观。文人对于这种“准则”评价出来的花情有独钟。譬如《爱莲说》中对莲花给予了“清廉”的期许:“予独爱莲之出淤泥而不染,濯清涟而不妖,中通外直,不蔓不枝,香远益清,亭亭净植,可远观而不可亵玩焉。”

宋代文人首创“焚香、点茶、挂画、插花”四艺。宫廷重视首设立“四司六局”专营四类项目。其中“排办局”专管插花项目。上行下效“四艺”成为官家的排场后,逐渐被民间所接受并成为时尚的标准。

宋人没有“彼岸花”,只有“理念花”,即人们熟知的“梅、兰、竹、菊”四君子,除此之外还有“松、柏、山茶、水仙”等。素雅清净,作为创作插花的依托和归宿,宋人以梅凌风傲雪;竹虚心有节;菊玉洁冰清;兰之虚怀若谷为最。

除了对于花本体认识之外融入了当时的文人喜好,甚至是小我的乖张,是宋人的一大特色。

比如,插花塑型本身并不自然,有一种偏狭的“变态”。有人用“枯枝单花”营造出个人品味的独感;还有用红花遍枝却“独留一叶”创制出无言的痛感,这种文人审美境界的变迁使得那个时代的美被升华了,被人为地向上托举,就像青春期被误解的少年,看似完全不可接受,但却充满着张力。恰恰这种张力,才使得很多的宋代的遗物,被我们后世誉为“天人之作”。

“花器”在宋代各大窑口(汝、哥、官、均、定、龙泉等)都出专用的花器,花纹简单,技巧平素,崇尚内敛。这样的花器才不会喧宾夺主,反倒可以“增色生香”。

为了让花枝能更好地塑型、构图和造型,宋人甚至发明了“多孔插花器”,七孔、九孔、十六孔、三十一孔的花器。同样,为了防止冬季冻伤花枝,很多的插花器中还设有用锡制作的内胆或管子。

古人对于摧花、培花、插花、赏花有着很深的认识和实际操作的经验。这些“神技”足以使人们高山仰止。至于中华的“活水”怎样滋养了日本的“清渠”又大有学问。但就插花的流派,看看日本对于菊花和梅花的热爱,就能大致体味到宋人的情趣了。