建筑、情绪与音乐

2016-04-09理查德科因RichardCoyne徐知兰TranslatedbyXUZhilan

理查德·科因/Richard Coyne徐知兰 译/Translated by XU Zhilan

建筑、情绪与音乐

理查德·科因/Richard Coyne

徐知兰 译/Translated by XU Zhilan

摘要:笔者利用心理学理论来论证音乐比建筑更能主导情感或心绪。论文从人们表达威胁或喜悦的那种对声音的迅速反应出发,将论述扩展至音乐如何影响人的期待。然而,本文也许只能揭示音乐与建筑的一部分与情感相关的潜能。马丁·海德格尔现象显示出这种体验层级的逆转。情感体验始于对世界的期待。建筑擅长创造一种期待的环境、一种氛围,也就是一种情绪,以及操作一段音乐上的不同时间维度。笔者以这种挑衅的观点结尾,为了使建筑唤醒密集的情感体验,而这又需要回到如何聆听一段音乐。

Abstract:I draw on psychological theory to suggest that music makes greater claims on the emotions than architecture. The story begins with people's immediate responses to sounds as indications of threats and pleasures, and progresses to the role of musical sounds in in fl uencing our expectations. I suggest that this narrative only accounts in part for the emotional potency of music and architecture. The phenomenology of Martin Heidegger would suggest a reversal of this experiential hierarchy. Emotional experience starts with expectations about the world. Architecture is good at creating a climate of expectations, an atmosphere, i.e. a mood, and operates over di ff erent time scales to a piece of music. I end with the provocative thought that in order for architecture to invoke intense emotional experiences it would need to replicate what it's like to listen to a piece of music.

关键词:建筑,情感,情绪,音乐

Keywords:architecture, emotion, mood, music

Architecture, Mood and Music

对我们大部分人来说,物理空间充满意义与情感——一些空间比另一些更为强烈。然而,我们步入一座建筑或面对宏伟景色时所体验到的情感,很少可与听到一首乐曲时所引起的情感的强烈程度相比拟,若音乐能应时、应景,或为本人所喜爱,就更是如此。

不过,两者(音乐与场所)的结合却可以带来震慑人心的效果。天主教堂的合唱音乐,甚至是用公共广播播放的安静轻柔的音乐,都能在情感上令参观者或祈祷者折服。契合环境的曲调或节拍,只要配上几个适当的和弦,音乐曲目就能放大、增强或消除来自城市环境的气氛。这就是许多电影需要配乐的原因。而且如果有了个人播放器,我们也可以随身携带自己的音乐和情绪调节器。也许,这也是我们有时更喜欢保持沉默、或对来自周边环境的声音不予理睬的原因。音乐对我们的情感常常具有过于强大的主导能力。

为什么音乐能够做到这些,而空间却很少能独立产生这样的作用呢?心理学家帕特里克·尤斯林和丹尼尔·法斯特加尔为理解音乐的情感效用提出了一个可能有说服力的理论框架,至少从进化心理学的观点来看是如此,其论述引用了500多篇论文[1]。其中并未提到建筑学,但我将在其论文的基础上提炼出音乐的情感效用高于建筑的结论。

1 音乐的作用机制

尤斯林和法斯特加尔总结了有关音乐与情感的文献,并将其归纳入一个共分6个层次的理论框架,从最原始的神经反射作用开始,到更微妙和多样的文化层面。

1.1首先最基本的,是声音与情感之间的神经联系,包括人类在内的大多数动物都有这种特征。情感会让我们对重要的事物产生警觉——包括威胁、安全,以及其他导致恐惧或愉悦的因素。突如其来的噪音、巨大的响声、不和谐音、快速的节奏、尖锐的高音、低频的振动以及这些模式的各种变化,会自动提示我们一件事物是否重要、危险、庞大,是否已经产生或将要产生威胁,并且作为一种反射作用它将“促进激活中枢神经系统”[1]564。这是原始且类似动物的大脑指挥身体反应行为。但这和音乐有什么关系呢?似乎音乐也建立在这些“战斗或逃离”的声响暗示和作用机制基础之上,通过更深层次的体验与认知被控制、夸大、缓和或加强。

可能空间体验也涉及与之类似的基本原始反射作用——譬如从高处俯视、靠近尖锐物体、突如其来的移动,以及威胁的姿势等,但那时你早已身陷危处,其他的反应就开始发挥作用。伴随着声音产生的强烈情绪会表现为准备和警告。想象连续的火灾警就能引发警觉情绪,即使在视线范围内没有可见的危险时也依然如此。与之类似的声音主导空间的更显而易见的例子是,舒适、温馨、质朴的声音可以给平凡的空间体验增色。

1.2尤斯林和法斯特加尔提出,在这些声音与情绪之间的原始反射作用之上还有一种“条件”反射。这是通过“一种情绪由一首乐曲触发,仅仅因为这种刺激已经与其他的正面或负面刺激因素一再重复匹配的缘故”而形成的过程。冰激凌的口味与质感可能让人想起童年时期在安乐的家中与家长共进晚餐时的场景。同样,卡朋特乐队的“靠近你”、或其他与之相似的歌曲和类似的韵律,都能够让人们在第一次聆听时引起同样的感受。

空间体验可能也与之有某种相似性——例如回到你青年时期的家中,在一座复古的博物馆里见到熟悉的旧商标,或翻阅所有那些数码相册时的场景。然而音乐可以无处不在的属性意味着其条件反射和产生追忆的过程可以随身携带且便于获得。在这一点上,音乐优于视觉刺激,并具有主导地位。

1.3刺激效应通常有共鸣作用。音乐声响在某些方面类似人类语音。我们倾向于情绪化地回应充满愤怒的人声:“如果人类的语音在速度很快、声音响亮而尖锐时会被理解为‘愤怒’,那么乐器声由于甚至可能更快、更响、更尖锐的特征也可能听起来极其‘愤怒’”[1]566。尤斯林和法斯特加尔形容音乐是“特别有效的情绪感染来源”。

他们把这种情绪感染与我们对视觉刺激的共鸣相联系,例如我们看见别人跳舞时自己也想用脚打节拍的镜像神经元反应[2]。有理由相信,空间体验大致上也涉及这类反应过程。但由于我们对人声具有天然亲近感,因此在倾听卡尔·奥尔夫的《布兰诗歌》开场合唱时所感受到的情绪之强烈,与人们在欣赏普桑的油画、山川景色或在暴风雨中冲到卡拉卡拉浴场感受到的情绪不可同日而语——而无论后者如何庄严崇高都同样如此。

1.4尤斯林和法斯特加尔也描述了音乐产生视觉形象的过程。因此,归功于各种不同的联想,人们才能在欣赏贝多芬的《田园交响曲》时,在脑海中浮现出阳光下令人惬意的草场景象。音乐在这里服从于空间体验。

然而尤斯林和法斯特加尔并未提到其反向过

Physical spaces are charged with meaning and emotion for most of us-some spaces more than others. But it's rare to enter a building or encounter spectacular scenery and experience the same intensity of emotion many of us feel on hearing a piece of music, particularly music that fi ts the mood of the moment, or the occasion, or is tuned to our predilections.

But putting the two together (music and place)can be electric. Choral music, or even soft music playing quietly over the public address system in a cathedral can overwhelm the visitor or worshipper, emotionally. The right ambient hum or beat or, just a few of the right chords as a music track can amplify, intensify or counteract the mood of the city. That's why fi lms have music, and with personal stereos we can carry our soundtrack and emotional switches around with us. Perhaps that's why some of the time we prefer silence, or to let the sounds of the environment do their work. Sometimes music is too powerful in driving our emotions.

Why does music achieve what space on its own can do only rarely? Psychologists Patrik Juslin and Daniel VästThäll o ff er a plausible framework for understanding the emotional potency of music, at least from the point of view of evolutionary psychology, with reference to over 500 articles[1]. They don't mention architecture, but I'll draw on their paper to a ffi rm the emotional potency of music over architecture.

1 Musical mechanisms

Juslin and Västfjäll summarise the literature on music and emotions and stack it into a six-tiered framework, starting from primitive neurological re fl exes to the more culturally nuanced and varied.

1.1 At base is a neurological connection between sounds and emotions in most animals, including humans. Emotions are what alert us to something really important-threats, safety and other causes of fear and pleasure. Sudden noises, loud sounds, dissonance, quick rhythms, high pitched sounds, deep rumbles, and changes in any of these patterns provide automatic cues that something important, dangerous, large, or threatening is happening or about to, and produces "increased activation of the central nervous system"[1] 564as a kind of re fl ex. This is primitive and animal-like brain-body behaviour. What has this to do with music? It seems that music is built on these fi ght or fl ight sonic cues and mechanisms, controlled, exaggerated, moderated and reinforced by further layers of experience and perception.

Presumably spatial experience implicates similar basic, raw reflexes-looking down from a height, approaching sharp objects, sudden movements, and threatening gestures, but by then you are already in the danger zone and other responses kick in. The emotional intensity accompanying sound acts as preparation and warning. Think of the arousal induced by a persistent fire alarm, even when there's no visible danger. A similar dominance of sound over space may be evident in the case of comforting, soothing, and unobtrusive sounds that colour homely spatial experiences.

1.2 Juslin and Västfjäll refer to a kind of "conditioning" placed over these primitive reflex reactions and emotions involving sound. This is a process whereby "an emotion is induced by a piece of music simply because this stimulus has been paired repeatedly with other positive or negative stimuli"[1]564. The taste and texture of ice cream may remind the adult diner of childhood hours in the security of a happy home. In the same way, Close to You by The Carpenters, and other songs a bit like it, or its familiar cadences, evoke feelings similar to when the music was fi rst heard.

Spatial experience might achieve something similar-returning to the home of your youth, seeing familiar old brands in a nostalgia museum, fl icking through all those digital photo albums-but the anywhere-anytime aspect of music implies a kind of portability and availability of this conditioning and recollection process that overwhelms and dominates visual stimulation.

1.3 Stimulus effects often start to operate in sympathy within one another. Music sounds a bit like speech in some respects. We are tuned to respond emotionally to an angry voice: "if human speech is perceived as 'angry' when it has fast rate, loud intensity, and harsh timbre, a musical instrument might sound extremely 'angry' by virtue of its even higher speed, louder intensity, and harsher timbre"[1]566. Juslin and Västfjäll describe music as a "particularly potent sources of emotional contagion."

They describe this emotional contagion in relation to the sympathetic response we have to visual stimulus, such as feeling like tapping our feet when we see someone dancing, i.e. the mirror neuron response[2]. Presumably spatial experience in general involves such processes. But because of our affinity with the human voice, listening to the opening chorus of Carl Or ff's Carmina Burana gets some people going with an intensity of emotion that a painting by Poussin, a mountain scene or a dash through the Baths of Caracalla in a rainstorm can't quite match-however sublime.

1.4 Juslin and VästThäll also describe how music has been known to generate visual imagery. So, thanks to various associations, someone listening to Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony is able to conjure up images of pleasant meadows in the sunlight. Here music is subservient to spatial experience.

But Juslin and Västfjäll don't speak of the converse-imagining or humming a particular (emotional) piece of music while walking in the countryside or sitting on the beach. They do however refer to research that proposes musical emotion is a particular category of emotion. Music that makes us happy does not come with the trappings or "beliefs" of everyday events that make us happy, such as passing an exam, being among people who care about us, or enjoying sunlight. Perhaps it's this detached, musical emotion devoid of association with actual life events that we seek rather than emotions embedded in everyday life.

1.5 They also associate music with episodic memory. A tune, a chord, or a cadence prompts recollection of particular events: an embarrassing school musical, a happy romance, a picnic on the beach.程——即在乡间散步或闲坐于沙滩上时,是否能想象或哼唱某首(特定情绪)的音乐。但他们确实提到,有相关研究提出音乐情绪属于情绪的某种类型。令人愉悦的音乐并不必需对令人愉快的日常事件的外在表征或“信念”相伴,如通过考试、与关心我们的人在一起或沐浴阳光等。也许相比于来自日常生活的种种情绪,正是这种超然的音乐情感——不需要依赖真实的生活事件——才更令人向往。

1.5他们也将音乐与片断记忆相联系。一首曲子、一个和声或某种曲式激发了对特定事件的回忆——也许是令人尴尬的学校音乐,也许是美妙的浪漫故事,或是一次沙滩上的野餐。

它与空间记忆术、或由空间体验而触发的回忆有共同之处。显然,在成年人的记忆中最活跃的是产生于15~25岁之间的记忆——即“记忆隆起”[1]567时期。因此,成年人会在之后的生活中对他们在此期间接触到的流行音乐有更强烈的情绪反应。由此可以推断,空间的体验和有形的纪念物也提供了类似的情感记忆,却缺乏音乐可以无处不在和反复接触的性质,因此也没有那么多机会深深植入和丰富我们的情感库。

1.6音乐充满许多人们熟悉的形式与风格,会让我们产生期待。如果音高E紧跟在C后面出现,那么我们就会期待下一个出现的音高是G,这样就能形成一个三和弦。而吉他的G7和弦则应以C和弦为解决和弦。符合这些规律还是违背它们,将激起人们的满足感或沮丧感。我感到类似的规律也存在于空间体验和空间的语汇中。期待在本质上主导了认知。

音乐的情感与由空间或建筑环境引起的情感有些许不同之处。音乐引起的情感反应在瞬间的转换中可以被激发或消除。音乐性的情感是立刻反应的。而与空间和场所相关联的情感则长期存在,且在某种程度上更微弱,并时刻准备被音乐加强或抵消。因此如果说建筑空间改变的是情绪[3]而不是情感会更准确。

尤斯林和法斯特加尔的研究成果似乎加强了一种观念,即认为音乐在激发情感上超越了其他艺术。也许无论建筑对情感如何驱使,都难以摆脱音乐的暗示。或许,建筑师只是通过营造更崇高庄严、精美绝伦、气势磅礴或温馨朴素的建筑来呼应音乐所取得的效果。但还有一个关于建筑与音乐的解释:建筑设定气氛,然后音乐才可以影响我们的情感。想想看安静地迎接唱诗班的第一句赞美诗或尖塔上第一声钟鸣的大教堂吧。

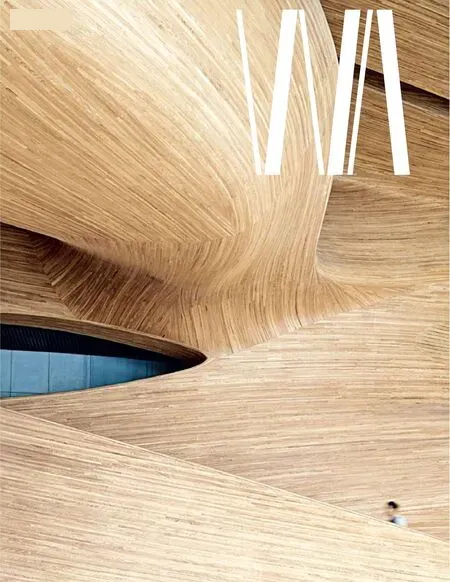

1 西班牙圣地亚哥-德孔波斯特拉的弥撒曲/Mass in Santiago de Compostela, Spain

2 希腊迈泰奥拉修道院/Great Meteoron Monastery, Meteora, Greece(1.2摄影/Photos: 理查德·科因/Richard Coyne)

2 体验为先

尤斯林和法斯特加尔有关音乐情感的本体论固然提出了一套从最原始到具有更复杂文化意义的序列,也提出了我们对所处环境中的刺激进行反应的观点。重要的是,马丁·海德格尔和许多现象学理论家认为,期待不可抗拒地主导认知[4],这一观点将推翻这一系列优先次序。因此,在现象学的观点看来,“应激反应”模式作为这种解释理论的出发点,其实是人们对于在环境中体验声响的过程赋予了特定的结构,并由此总结出一些实用的实验规律和数学规律。

在此过程中,应激反应无疑解除了整个语境的特权,我们的空间体验正是建立在其中的特定结构,这一语境包括各种记忆、化身、所有感受、情绪及文化背景等。

我也倾向于从解构主义阅读——如雅克·德里达倡导的——角度对这些情感理论做些分析[5, 6]。我不禁认为,情感源自我们内在生命与环境之间的密切联系,而电影、戏剧或音乐所提供的情感仅仅是对真实情感体验的再现或模仿。寺田丽在比较文学领域撰写过一篇颇具启发意义的文章,提出了相反的观点:“情感有赖于想象”和“想象有赖于戏剧性”[5]206。举一个过度阐释的例子——为能真正感受到他人的痛苦,我们必须将受苦者视为一本书中的人物来看待。就建筑与音乐的而言,我们也可以说,为了对山顶上的修道院或尼泊尔的博德纳大佛塔之类的建筑中感受情绪,我们必须复制倾听一段音乐的状态——也许是菲利普·格拉斯的《机械生活》(1988年),或是采用这首配乐的同名电影(高佛雷·雷吉奥导演)。在情感领域里,艺术引领生活。

我在《场所中的调谐》[7]和《情绪与可移动生活》[8]中对这些主题和其他主题进行了分析。后者探讨了移动设备、智能手机和社交媒体如何影响我们的情绪。我们对建筑的体验也正越来越多地受到随身携带的通讯设备影响,一定程度上是因为它们赋予了我们接触声音与音乐的机会。□

There's a correspondence here with spatial mnemonics, or the memories conjured up by spatial experience. Apparently recollections in adulthood are most vivid for the period between age 15~25-the "reminiscence bump"[1]567-hence the stronger emotional response of adults later in life to the pop music they were exposed to during that period. Presumably spatial experience and physical memorabilia provide similar emotional recollections, but without the ubiquity of music and repeated exposure, and its opportunities to bed down and contribute to our emotional reservoirs.

1.6 Music is redolent with familiar forms and patterns that lead us to expect certain things to happen. If the note C is followed by E then we expect the next note in the sequence to be G to make a triad. The G7 guitar chord ought to resolve to the C chord. The satisfaction or denial of these rules provokes a sense of satisfaction or frustration. I have a feeling there's something similar about spatial experience, and spatial languages. Perception is driven substantially by expectations.

There are some differences between musical emotions and emotions induced while in a spatial or architectural setting. Emotional responses to music can be switched on and off at the flick of a switch. Musical emotions are immediate. Emotions associated with spaces and places are longer term, and in a sense weaker, ready to be reinforced or counteracted by music. It's more accurate to ascribe architectural spaces to moods[3]rather than emotions.

The studies to which Juslin and Västfjäll refer seem to reinforce the emotional superiority of music among the arts. Perhaps after all, any claim architecture may have on the emotions is just a shadow of what music has to offer. Perhaps in creating sublime, beautiful, dramatic or homely spaces, architects are simply trying at best to echo what music achieves. But there's an alternative account of the architecture-music relationship: architecture sets the mood so that music can do its work on our emotions. Think of the cathedral in a state of repose awaiting the fi rst strains of a choral anthem or the chime of the steeple bells.

2 Putting experience fi rst

Of course Juslin and Västfjäll's ontology of musical emotions suggests a progression from the primitive to the more culturally sophisticated, and from the idea that we respond to stimuli in our environment. Importantly, for Martin Heidegger[4]and the phenomenologists, perception is driven overwhelmingly by expectation, which would reverse this series of priorities. So from a phenomenological viewpoint the stimulus-response model with which this account begins is a particular construction that people place on the experience of sound in the environment, leading to the identi fi cation of particular experimental and mathematical regularities.

In the process such stimulus-response accounts arguably de-privilege the whole context in which our spatial experience is constructed, including memories, embodiment, the full range of the senses, moods, and the cultural contexts within which we experience space.

I'm also inclined towards the contribution to theories of emotion from a deconstructive reading, for example, as advanced by the philosopher Jacques Derrida[5,6]. It's tempting to think of emotions as emerging from an intimate compact between our inner lives and the environment, and that emotions as purveyed in film, theatre or music are merely secondary copies or simulations of authentic emotional experience. An illuminating article by Rei Terada from the field of comparative literature, proposes the opposite: "Emotion depends on imagination" and "imagination depends on theatricality"[5]206. As an overstated example: in order to really feel pity for someone else's pain we need to see the sufferer as if a character in a book. In the case of architecture and music we could say, that in order to feel emotionally about a work of architecture such as a monastery perched on amountaintop, or the Boudhanath Stupa in Nepal, we need to replicate what it's like to listen to a piece of music: perhaps Philip Glass' Powaqqatsi (1988), or watch the fi lm in which it's represented (by Godfrey Reggio). In the realm of the emotions, life takes its lead from art.

I examine these and other themes in the books The Tuning of Place[7]and Mood and Mobility[8]. In the latter I explore how mobile devices, smartphones and social media also influence our moods. Our experience of architecture is increasingly mediated by the communications devices we carry about with us, in part because of the access they give us to sound and music.□

参考文献/References:

[1] Juslin, Patrik N., and Daniel Västfjäll. Emotional Responses to Music: The Need to Consider Underlying Mechanisms. Behavioural and Brain Sciences, 2008, (31)559-621.

[2] Molnar-Szakacs, Istvan, and Katie Overy. Music and Mirror Neurons: From Motion to 'e'motion. SCAN, 2006, (1)235-241.

[3] Wigley, Mark. The Architecture of Atmosphere. Daidalos, 1998, (68)18-27.

[4] Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. John Macquarrie, and Edward, Robinson, trans.. London: SCM Press, 1962.

[5] Terada, Rei. Imaginary Seductions: Derrida and Emotion Theory. Comparative Literature, 1999, (51) 3, 193-216.

[6] Coyne, Richard. Derrida for Architects. Abingdon: Routledge, 2011.

[7] Coyne, Richard. The Tuning of Place: Sociable Spaces and Pervasive Digital Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010.

[8] Coyne, Richard. Mood and Mobility: Navigating the Emotional Spaces of Digital Social Networks. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016.

收稿日期:2015-12-21

作者单位:爱丁堡大学