The first discovery of Urmiatherium (Bovidae, Artiodactyla) from Liushu Formation, Linxia Basin

2016-03-29SHIQinQinWANGShiQiCHENShaoKun3LIYiKun

SHI Qin-QinWANG Shi-QiCHEN Shao-Kun,2,3LI Yi-Kun,2

(1Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences,Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology,Chinese Academy of SciencesBeijing 100044 shiqinqin@ivpp.ac.cn)

(2University of Chinese Academy of SciencesBeijing 100039)

(3Three Gorges Institute of Paleoanthropology,China Three Gorges MuseumChongqing 400015)

The first discovery of Urmiatherium (Bovidae, Artiodactyla) from Liushu Formation, Linxia Basin

SHI Qin-Qin1WANG Shi-Qi1CHEN Shao-Kun1,2,3LI Yi-Kun1,2

(1Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences,Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology,Chinese Academy of SciencesBeijing 100044 shiqinqin@ivpp.ac.cn)

(2University of Chinese Academy of SciencesBeijing 100039)

(3Three Gorges Institute of Paleoanthropology,China Three Gorges MuseumChongqing 400015)

A new skull ofUrmiatherium intermedium(Bovidae, Artiodactyla) from the Linxia Basin, Gansu Province is described here.U. intermediumis a large Late Miocene bovid with an odd-looking horn apparatus, consisting of a pair of degenerate, closely situated horn-cores, and a large area of exostoses on the frontal and the parietal bones. Plenty of skulls, teeth, and bone fragments ofU. intermediumhave been reported from North China, but the skull to be described is the fi rst discovery from the Linxia Basin, expanding the geographic distribution ofU. intermediumto the northeast edge of the Tibetan Plateau. AlthoughUrmiatheriumis generally thought to be closely related toPlesiaddax,Hezhengia,Tsaidamotherium, and some other Late Miocene “ovibovines”, the phylogenetic position ofUrmiatheriumis still in debate. The distribution ofUrmiatheriumis wide, spanning from Iran to North China.Urmiatheriumseldom accompanies with other Late Miocene “ovibovines” in North China, but is accompanied by other bovids likeSinotragus.

Linxia Basin, Late Miocene, Bovidae,Urmiatherium

1 Introduction

Urmiatheriumis a large Late Miocene bovid, with odd-looking horn apparatus, shortened cranium, perpendicular cranial roof, and thickened basicranium. The horn apparatus is composed of short, posteriorly positioned, and closely inserted horn-cores, sometimes partially fused at the base, and elongated horn bases with very rough surfaces. The exostoses are well developed on the frontal and/or the parietal bones.

There are two species ofUrmiatherium, the type speciesU. polakifrom Maragheh, and another speciesU. intermediumfrom North China. The material ofU. polakiis rare, comprised of three partial skulls (two posterior parts and one facial part), several cervical vertebrae,isolate teeth, broken mandibles and limb bones, most of which are poorly preserved (Rodler, 1889; Mecquenem, 1925; Kostopoulos and Bernor, 2011; Jafarzadeh et al., 2012). All the specimens were discovered in Maragheh, but from different localities (Karajabad and Ilkhchi), representing different geological ages (Middle and Upper Maragheh, 8.16-7.9 Ma and 7.9-7.4 Ma separately) (Mirzaie Ataabadi et al., 2013). The other species,U. intermedium, on the contrary is represented by abundant materials: approximately 20 skulls, large numbers of lower dentitions, isolated teeth and bone fragments (Schlosser, 1903; Bohlin, 1925, 1935a). Most of the specimens were found from the localities in Baode (Anderson locs. 30, 43, 44, 49, 108), and only one skull and some fragments from Qingyang (Anderson locs. 115, 116). The age ofU. intermediumin Baode spans from ca 7.0 Ma (loc. 49) to ca. 5.7 Ma (loc. 30), according to Kaakinen et al. (2013).

Recently, a skull ofUrmiatherium intermedium, IVPP V 18955, was discovered from the Linxia Basin, Gansu Province, Northwest China. It was discovered from the locality LX0029, near the Huaigou village, which is approximately 10 km southeast to the Hezheng County (Fig. 1). The skull was excavated from the upper Liushu Formation, and belongs to the Late Miocene Yangjiashan Fauna of the late Bahean age, spanning from ca. 8.7 to 7.2 Ma (Deng et al., 2013). Thus, the stratigraphic age of the new skull in the Linxia Basin is slightly earlier than those from Baode, and is almost contemporary withP. polakifrom Maragheh. Although there are plenty of Late Miocene bovids in the Linxia Basin, it is the fi rst discovery ofUrmiatheriumthere, expanding the distribution ofU. intermediumto the northeast edge of the Tibetan Plateau.

Institutional abbreviations DOE, Department of Environment, Iran; IVPP, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China; PIUU, Paleontological Institute, University of Uppsala, Sweden.

Fig. 1 The sketch map of China and the Linxia Basin, showing the fossil locality LX0029 near the Huaigou village

2 Systematics

Pseudobos intermediumSchlosser, 1903

Pseudobos sinensisSchlosser, 1903

Chilinotherium tingiWiman, 1922

Lectotype PIUU M 3943 (Bohlin, 1935a: Ex. 1, loc. 30; text fi g. 1, pl. 1, fi gs. 1-3).

Described specimen IVPP V 18955, a male adult skull (Figs. 2-4).

Description The new skull, IVPP V 18955, is compressed severely from side to side, and splits into two parts along a plane from the posterior part of the nasal to the pterygoid, but is restored very well with plaster. Although the cranium is severely damaged (especially the occiput), the horn apparatus is preserved in a relatively good condition. The cheek tooth rows are almost intact, except that P2 are missing in both sides. The muzzle in front of the cheek teeth is missing.

The basioccipital is thick, short and rectangular (Fig. 2A, C: Bo). The posterior tuberosities protrude ventrally and fuse together, leaving only a narrow groove in the ventral view (Fig. 2C: PosT). The posterior facets of the posterior tuberosities are almost square, with a shallow depression in the center. In the lateral view, the facets form an angle of about 120° with the ventral border of the bacioccipital (Fig. 2A). The anterior tuberosities are slender and ridge-like. The condyles and paroccipital processes are broken in both sides. A small part of left accessory articular surface is observable, indicating a shallow depression between the condyle and the paroccipital process (Fig. 2C, AAS). Both auditory bullae are missing. The oval foramina are moderately large, facing laterally and anteriorly (Fig. 2C: VF). The pterygoid crests are sharp and protruding (Fig. 2A, C: PtC). At the root of the pterygoid crests lie the orbito-rotundum foramina, which can hardly be observed in the lateral view. The distance from the oval foramen to the orbito-rotundum foramina is nearly the same as that from the orbitorotundum foramina to the optic foramen (Fig. 2A: OpF). The ethmoidal foramen is small, lying in the center of the orbit (Fig. 2A: EmF).

The occiput is heavily damaged. The broken foramen magnum reaches the upper part of the occipital, exposing part of the brain cavity (Fig. 3: broken FM). Above the broken foramen, there is a large external occipital protuberance accompanied bilaterally by two deep depressions for the attachment of the nuchal ligament (Fig. 3: EOP). A small part of the right mastoid is also preserved (Fig. 3: Mas). The nuchal crest is sharp and protruding (Fig. 3: NC). Above the external occipital protuberances is the small supra-occipital (Fig. 3: SpO). The supra-occipital and the parietal suture is zigzag near the temporal fossa, but is undistinguishable in the center (Fig. 2A: suture ⑤). The parieto-temporal suture is simple and relatively straight, whereas theparieto-frontal suture is scarcely distinguishable (Fig. 2A: suture ④). The left temporal fossa is broken, exposing the lateral wall of the cranium of about 1 cm thick (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2 The skull ofUrmiatherium intermedium, IVPP V 18955 A. left lateral view; B. dorsal view; C. ventral view; the horn apparatus is divided into four sections (I, II, III, IV), according to Bohlin, 1935a; scale bar = 5 cm AAS. accessory articular surface; Bo. basioccipital; EmF. ethmoidal foramen; F. frontal; FM. foramen magnum; FS. frontal sinus; HA. horn apparatus; IoF. infraorbital foramen; J. jugal; L. lachrymal; LB. lachrymal bulla; LHc. left horn-core; M. maxilla; MT. maxillary tuberosity; OpF. optic foramen; PF. palatine foramen; Pl. palatine; PostT. posterior tuberosity; PtC. pterygoid crest; RHc. right horn-core; SoF. supraorbital foramen; SoG. supraorbital groove; SPP. pterygoid process of sphenoid; VF. oval foramen Arrows: ① fronto-lachrymal suture; ② lachrymo-jugal suture; ③ maxillo-jugal suture;④ parieto-temporal suture; ⑤ suture between parietal and supra-occipital The double-arrows in B indicate the grooves medial to the real horn-cores

Fig. 3 Posterior view of the skull ofUrmiatherium intermedium, IVPP V 18955 The horn apparatus is divided into four sections (I, II, III, IV), according to Bohlin, 1935a; scale bar = 5 cm EOP. external occipital protuberance; FM. foramen magnum; Mas. mastoid exposure; NC. nuchal crest; SpO. supraoccipital

Fig. 4 Sketch of the right upper cheek teeth ofUrmiatherium intermedium, IVPP V 18955, showing the buccal and occlusal view

The horn apparatus is large and complicated, forming a prominent bulge above the cranium, and covering the surfaces from the foremost point of the frontal to the rearmost point of the parietal, but without horn-cores in the proper sense (Figs. 2A, B). The division of the horn apparatus into four sections (elements) (I, II, III, and IV) proposed by Bohlin (1935a) is well applicable to the new skull (Figs. 2, 3). Section I is the horn-cores proper, which were described as “low and sharp ridge, on which in most male individuals the vertex is recognizable (Bohlin, 1935a:21, “…beim Mannchen ein Paar niedriger scharfer Kamme, an denen an den meisten Exemplaren die Spitze des Horns erkennbar ist.”). In the new specimen, the horncores proper are low and laterally compressed, and the vertexes are clearly shown, pointing upwards and backwards. In the dorsal view, thehorn-cores proper converge posteriorly, but remain separated at the rearmost point by a narrow deep fi ssure (Fig. 2B). Medial to the horn-cores proper, there are two deep grooves, separating the horn-cores proper from the bulging horn bases in the center (Fig. 2B, double-headed arrows). The horn bases between the horn-cores proper are very high, partially because of the compression and deformation of the skull. Anterior to the horn-cores proper, clear depressions are observed, separating the horn-cores proper from the exostoses on the frontal, whereas posterior to the horn-cores proper, the separation is vague. Anterior to the horn-cores proper, the horn bases raise high above the orbit, composing the main part of the horn apparatus, which was de fi ned by Bohlin as sections II and III (Bohlin, 1935a). These two sections are exostoses expansion on the frontal, with highly cancellous surfaces. Because of the severe deformation, the border between the sections II and III in the new specimen is hard to distinguish. Sections I, II and III vary greatly in different individuals. Posterior to the horn-cores proper, the exostosis expansion on the parietal is also well developed, reaching the rearmost point of the parietal, which was de fi ned as section IV. In some individuals, the exostoses on the left and right sides fuse together, but in most individuals as well as in the new specimen, they are separated by a deep narrow fi ssure along the sagittal line (Fig. 3: fi ssure). In the new specimen, the fi ssure is long, and the surface of the exostoses is very rough, indicating that section IV of the new specimen is better developed than in most skulls from Baode and Qingyang (Bohlin, 1935a).

The frontals are partially damaged, exposing the porous inner structures (Fig. 2A: FS). On the right side, the surface bone lamina above the orbit has almost gone, showing that the frontal sinuses are so well developed that the frontals are fi lled with large air cavities and thin supporting bone laminas. The supra-orbital foramina are small, sunken deeply in the frontals and facing forwards (Fig. 2A: SoF). The supra-orbital grooves are distinct and long (Fig. 2A: SoG). The internal openings of the supra-orbital foramina are also small, facing mostly downwards. The canal between the external and internal openings of the supra-orbital foramen is long (about 4 cm). The anterior border of the orbital rim is posterior to the back of M3.

The lachrymals are rectangular and large (Fig. 2A: L). The fronto-lachrymal sutures (Fig. 2A: suture ①) and the lachrymo-jugal sutures (Fig. 2A: suture ②) are complicated, especially near the orbital rim. On the orbital surface of the lachrymal, there is a large lachrymal bulla (Fig. 2A, LB). Jugals are relatively small, with two clear lobes (Fig. 2A: J). Most of the nasals and the anterior parts the maxillae are missing. The infra-orbital foramina are small, opening at the level between P3 and P4 (Fig. 2A: IoF).

In the ventral view, the maxillo-palatine suture is hard to determine. The palatine foramina are small, situated at the level of the posterior lobe of M2 (Fig. 2C: PF). The anterior edge of the choanae is V-shaped, with its anterior point situated posterior to the tooth rows and the lateral identations.

The cheek teeth are hypsodont. The premolar rows are short, and the length ratio of premolar to molar row is approximate 55.8%. P2 are missing on both sides, but the root of the right P2 is preserved. The paracone of P3 is anteriorly positioned, separated from the sharpparastyle by a narrow groove. The metastyle of P3 is large. P4 is similar to P3 in length, but is a little wider. The lingual border of P4 is fl at, making P4 almost square in shape. The buccal border of P4 is almost symmetrical and the paracone rib is weak. The central fossettes of P3 and P4 are deep and narrow. M1 is slightly longer than wide. The buccal ribs are weak, and the metastyle is unrecognizable. The lingual wall is fl at. There are two enamel islands in M1: the larger oval lingual one and the much smaller buccal one. M2 is longer than M1. Both parastyle and mesostyle are well developed, but the latter is thinner. The metastyle and metacone rib are weak, whereas the paracone rib is moderately developed. There is only one enamel island in M2. M3 is almost as long as M2, but the occlusal surface of M3 is a little narrower, especially the posterior lobe. The ribs and styles are well developed, except the metacone rib. In both M2 and M3, the lingual wall of the fossettes protrudes medially and posteriorly. In all molars the lingual valleys are shallow. No basal pillars are present.

3 Comparisons

3.1 Comparison with the specimens from Baode and Qingyang

The new skull has a large horn apparatus expanding from almost the foremost point of the frontal till to the rearmost point of the parietal, forming a large bulge on top of the cranium, in accordance with that ofUrmiatheriumintermedium. The features of the skull, such as the short cranium, the perpendicular cranial roof, the thickened basicranium and enlarged posterior facet of the posterior tuberosities of the basioccipital, the small supraorbital foramen and distinct supraorbital groove, also show that the new skull has a close af fi nity withU. intermedium. The teeth of the new skull are similar with those ofU. intermediumby having short premolar rows, hypsodont crowns, and simple central cavities. Thus, the new specimen should be assigned toU. intermediumwith no doubt.

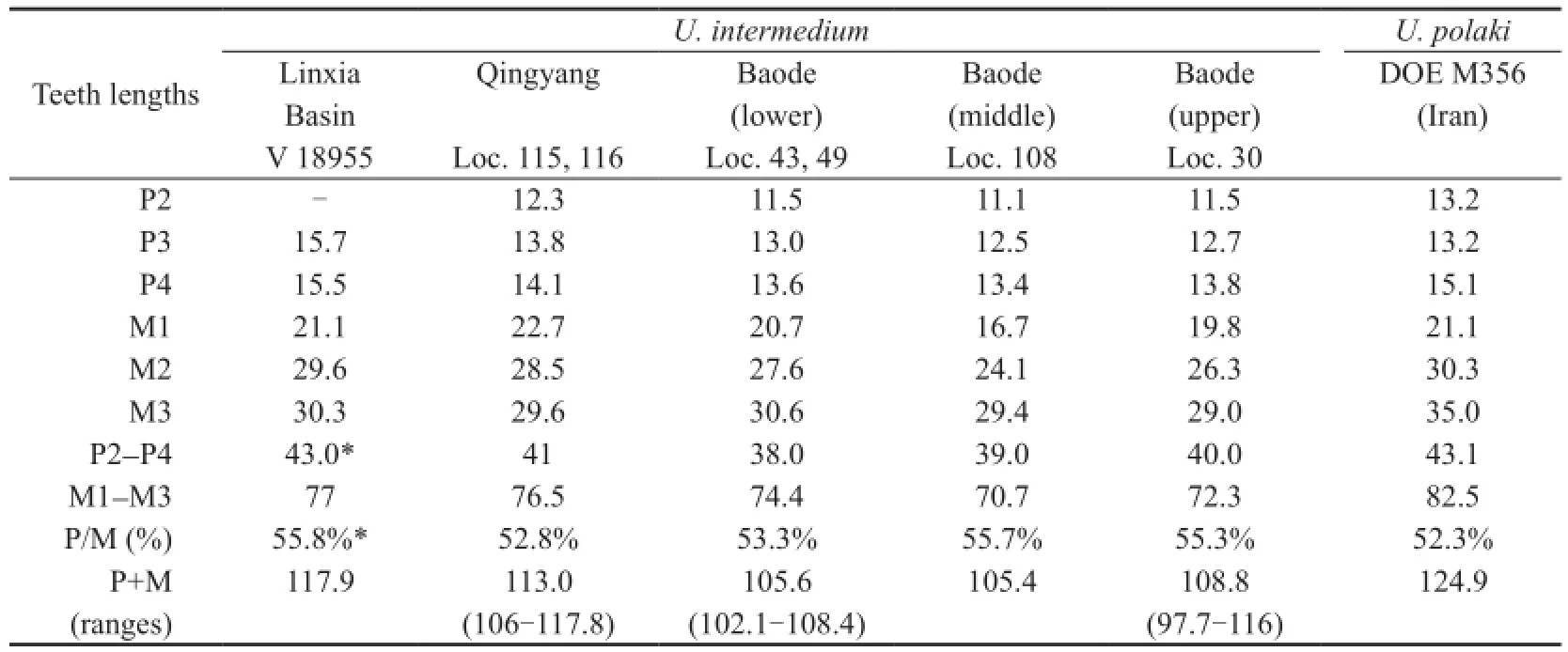

However, the new skull is larger than most of theU. intermediumskulls found from North China. Both of the lengths of the skull (Table 1: measurement 7) and the horn apparatus (Table 1: measurement 1) of the new skull are close to those of the largest individuals from Baode (loc. 30), whereas the new skull is longer than the only skull from Qingyang (Table 1: measurement 7). The dentition of the new skull (Table 2, P+M) is the largest among all knownU. intermedium, with its length close to the largest ones from Qingyang (loc. 115) and Baode (loc. 30). The individual variations ofU. intermediumis large (in the locality with most skulls, i.e. loc. 30, the length of the largest skull is 15% larger than that of the smallest skull, whereas in the length of the dentition, this ratio achieves up to 19%.), and the new skull does not exceed the variation ranges ofU. intermedium.

The morphology of the horn apparatus, especially the exostoses on top of the parietal varies greatly in different individuals, as Bohlin (1935a) pointed out. In the new specimen, the exostoses on section IV are very well developed, as in PIUU M 3934 (Ex. 7, loc. 108; Bohlin, 1935a: text fi g. 12 & 13), whereas in most specimens from Baode and Qingyang, section IVis smaller and smoother. However, section I and II of the horn apparatus of the new skull are different from that of M 3934, but more similar with Ex. 15 of loc. 30 (Bohlin, 1935a: text fi g. 14), with flatter surfaces in the front, a clear sagittal furrow between the posterior part of section I, and thin bone plates along the horn-cores proper which converging backwards.

Table 1 Skull measurements and comparisons ofUrmiatherium(males only) (mm)

Table 2 Tooth measurements and comparison ofUrmiatherium(mm)

Considering the great individual variations ofU. intermedium, Bohlin (1935a) distinguished three possible types mainly by size, development of section IV of the horn apparatus, and shape of p4 (type I, material from loc. 30; type II, material from loc. 108 and ?49; type III, material from loc. 115; material from other localities are uncertain). Here in this paper, we group the specimens by locations and stratigraphic layers (according to Kaakinen et al., 2013), and the measurements of the skulls and dentitions are compared (Table 1, 2). Theresult shows that there are no distinct differences among the materials from different layers or locations. Although the material from loc. ?49 is relatively small, other specimens from the same stratigraphic layer (e.g. loc. 43) is larger, and thus the variations might come from inadequacy of specimens, other than different types.

3.2 Comparison withUrmiatherium polakiandParurmiatherium

The type species,U. polaki, is similar toU. intermediumin having closely inserted horncores proper, exostoses on the frontals, perpendicular cranial roof, stout occipital condyles, and thickened basicranium. However, their differences are also signi fi cant, which was commented by Bohlin as possible difference of generic value (Bohlin, 1935a:37, “…sind vielleicht als Gattungsmerkmale hinreichend”). The skull ofU. polakiis longer and much wider than that ofU. intermedium(Table 1, measurements 3-5, 8-10), and its dentition is also longer, with a similar premolar to molar ratio (Table 2). The horn-cores ofU. polakiare longer, whereas the exostoses are less developed and are not extended to the parietal. The basicranium ofU. polakiis thicker, with a larger oval posterior facet of the posterior tuberosities.

The two posterior partial skulls ofU. polakiwere thought to be ontogenetically different, considering the differences of the horn-cores (Mecquenem, 1925; Kostopoulos and Berner, 2011). However, the fully developed basicraniums of the twoU. polakiskulls indicate that both of them are fully adult, and usually in adult bovids, the horn-cores would not grow permanently with age. Besides, although the horn-cores of the holotype are smaller, the surface on the frontal is coarser, and exostoses on the frontal always grow larger and rougher with age. Thus, the two skulls ofU. polakiin Maragheh should present different individual variations, other than ontogenetical stages, if they belong to the same species.

Parurmiatheriumshows great similarities toUrmiatheriumin the cranium and basicranium and is considered a late synomyn ofUrmiatheriumby some researchers (Gentry, 2010; Kostopoulos, 2009, 2014). Considering the poor preservation condition ofParurmiatheriumspecimens (all the skulls from Samos and Iraq are broken), it is hard to say that whetherUrmiatheriumandParurmiatheriummerit generic distinction. Anyway, the differences of the horns are obvious. The horn bases ofParurmiatheriumapproach each other anteriorly and the horn-cores are homonymously spiraled and widely apart, whereas inUrmiatheirum, the horn bases approach each other posteriorly and the horn-cores are straight and sometimes fused at the base. The exostoses on the frontals are well developed inUrmiatherium, forming a single piece of rough surface which also exists in females, whereas inParurmiatheium, the horn-cores are clearly separated. Thus,Parurmiatheriummight be retained before more specimens to be found.

4 Discussions

4.1 Phylogeny

The phylogeny ofUrmiatherium(andParurmiatherium) is in debate, because of itspeculiar horn apparatus and skull. Sickenberg established a new subfamily Urmiatheriinae forUrmiatheriumandParurmiatherium(Sickenberg, 1933), whereas Bohlin assignedUrmiatheriumto the subfamily Ovibovinae, together with the generaPlesiaddaxandTsaidamotherium, considering their similarities to the modernOvibos(Bohlin, 1935a). Bohlin’s opinion was followed, andUrmiatheriumwas described as a Late Miocene “ovibovine”by many researchers (Qiu et al., 2000). In 1987, the tribe Urmiatheriini was established by Köhler, includingUrmiatheriumas well asTsaidamotherium,Criotherium,Parurmiatherium, andPlesiaddax(Köhler, 1987). Later Chen and Zhang (2004, 2009) assigned more Late Miocene bovids into Urmiatheriini, and reestablished the subfamily Urmiatheriinae. The new Urmiatheriini share similar members with the Late Miocene “ovibovines”, and the main difference is their relationship with the extantOvibos.Urmiatheriumare also assigned to Oiocerini by Kostopoulos, mainly based on the homonymously twisted horn-cores ofParurmiatherium(Kostopoulos, 2014). In this paper, we use the term Late Miocene“ovibovines” temporarily, following the traditional way.

When Bohlin assigned the Late Miocene “ovibovines” to Ovibovinae, the morphologies of the basicranium are thought to be important, and we consider it reasonable. Although the thickened basicranium and the enlarged posterior tuberosities might to be highly related to the behavior of fighting and competing among males, other characters, such as the shallow depression between the occipital condyle and the paraoccipital process and the developed accessory articular surface at the bottom of the depression, are less common and might be phylogenetically related. The basicraniums of the Late Miocene “ovibovines” are very short, which is different from other Late Miocene bovids like caprines and boselaphines. The development of the exostoses is also a common trait of the Late Miocene “ovibovines” andOvibos, which is seldom observed in other bovids. Other similarities include: short braincase, short and stout condyles, mesodont or hypsodont teeth, and simple fossettes of the molars. Whether the Late Miocene “ovibovines” andOvibosform a monoclade is hard to say, but they share more similarities than with any other bovids.

4.2 Distribution

The distribution ofUrmiatheriumis wide, spanning from Iran to North China, whereas most other Late Miocene “ovibovines” are local.Tsaidamotherium,Shaanxispira,Lantiantragus, andHezhengiaare found only from North China, whereasParurmiatherimis found in Greece and the West Asia (Sickenberg, 1933; Bohlin, 1935b; Bouvrain et al., 1995; Qiu et al., 2000; Zhang, 2003; Chen and Zhang, 2004; Kostopoulos, 2009; Shi, 2014; Shi et al., 2014).Plesiaddaxis another wide spread Late Miocene “ovibovine”, distributed from the western Turkey to North China (Bohlin, 1935a; Bosscha-Erdbrink, 1978; Qiu, 1979; Köhler, 1987; Xue et al., 1995; Deng et al., 2011). However, thePlesiaddaxspecimens from Turkey might be problematical: the specimens from Kayadibi are very few and fragmentary and lacking crucial characters; the specimens from Garkin are abundant, but they are probably notPlesiaddaxeither. Thus, the distribution ofUrmiatheriumis wider than most of the other Late Miocene “ovibovines”.

Although several Late Miocene “ovibovines” species are discovered in the Linxia Basin (Urmiatherium,Tsaidamotherium,Hezhengia, twoShaanxispira, and an unpublished new genera), none of them are found in companion withUrmiatherium. OneShaanxispiraspecies is found from the same stratigraphic layer, but their localities do not overlap (Deng et al., 2013). Another contemporaneous Late Miocene “ovibovines” in the North China isPlesiaddax, but most specimens ofUrmiatheirumandPlesiaddaxcome from different localities. In the Linxia Basin, the only other bovid found from the same locality withUrmiatheriumisSinotragus, a caprine reported from both Turkey and China (Bohlin, 1935a; Geraads et al., 2002; Deng et al., 2013). In North China,Sinotragusand its possible synonymProsinotragusare also found from Baode and Qingyang, where they are accompanied withUrmiatheriumas well.

Acknowledgements We thank QIU Zhan-Xiang and DENG Tao for their advices in the research. We thank SU Dan for the preparation of the specimen and GAO Wei for photographing.

Bohlin B, 1925.Urmiatherium intermedium(Schlosser). Bull Geol Surv China, 7: 111-113

Bohlin B, 1935a. Cavicornier der Hipparion-Fauna Nord-China. Palaeont Sin, Ser C, 9: 1-166

Bohlin B, 1935b.Tsaidamotherium hedini, n. g., n. sp.. Geogr Ann, 17: 66-74

Bosscha-Erdbrink D P, 1978. Fossil Ovibovines from Grakin near Afyon, Turkey (I) and (II). Proc K Ned Akad Wet, B, 81: 145-185

Bouvrain G, Sen S, Thomas H, 1995.Parurmiatherium rugosifronsSickenberg, 1932, Ovibovine (Bovidae) from the Late Miocene of Injana (Jebel Hamrin, Iraq). Geobios, 28: 719-726

Chen G F, Zhang Z Q, 2004.Lantiantragusgen. nov. (Urmiatherinae, Bovidae, Artiodactyla) from the Bahe Formation, Lantian, China. Vert PalAsiat, 42: 205-215

Chen G F, Zhang Z Q, 2009. Taxonomy and evolutionary process of Neogene Bovidae from China. Vert PalAsiat, 47: 265-281

Deng T, Liang Z, Wang S Q et al., 2011. Discovery of a Late Miocene mammalian fauna from Siziwang Banner, Inner Mongolia, and its paleozoogeographical signi fi cance. Chin Sci Bull, 56: 526-534

Deng T, Qiu Z X, Wang B Y et al., 2013. Late Cenozoic biostratigraphy of the Linxia Basin, northwestern China. In: Wang X M, Flynn L J, Fortelius M eds. Fossil Mammals of Asia: Neogene Biostratigraphy and Chronology. New York: Columbia University Press. 243-273

Gentry A W, 2010. Bovidae. In: Werdelin L, Sandersn W J eds. Cenozoic Mammals of Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press. 741-796

Geraads D, Gülec E, Kaya T, 2002.Sinotragus(Bovidae, Mammalia) from Turkey and the Late Miocene Middle Asiatic Province. Neues Jahrb Geol Paläontol Monatsh, 8: 477-489

Jafarzadeh R, Kostopoulos D, Daneshian J, 2012. Skull reconstruction and ecology ofUrmiatherium polaki(Bovidae, Mammalia) from the upper Miocene deposits of Maragheh, Iran. Paläontol Z, 86: 103-111

Kaakinen A, Passey B, Zhang Z Q et al., 2013. Stratigraphy and paleoecology of the classical dragon bone localities of Baode County, Shanxi Province. In: Wang X M, Flynn L J, Fortelius M eds. Fossil Mammals of Asia: Neogene Biostratigraphy and Chronology. New York: Columbia University Press. 203-217

Köhler M, 1987. Boviden des türkischen Miozäns (Känozoikum and Braunkohlen der Türkei). Paleont Evol, 21: 133-246

Kostopoulos D S, 2009. The Late Miocene mammal faunas of the Mytilinii Basin, Samos Island, Greece: New Collection. 14. Beitr Paläont Österr, 31: 345-389

Kostopoulos D S, 2014. Taxonomic re-assessment and phylogenetic relationships of Miocene homonymously spiral-horned antelopes. Acta Palaeontol Pol, 59: 9-29

Kostopoulos D S, Bernor R, 2011. The Maragheh bovids (Mammalia, Artiodactyla): systematic revision and biostratigraphiczoogeographic interpretation. Geodiversitas, 33: 649-708

Mirzaie Ataabadi M, Bernor R, Kostopoulos D S et al., 2013. Recent advances in paleobiological research of the Late Miocene Maragheh Fauna, northwest Iran. In: Wang X M, Flynn L J, Fortelius M eds. Fossil Mammals of Asia: Neogene Biostratigraphy and Chronology. New York: Columbia University Press. 546-565

Mecquenem R de, 1925. Contribution à l’étude des fossils de Maragha. Ann Paléontol, 14: 1-36

Qiu Z D, 1979. Some mammalian fossils from the Pliocene of Inner Mongolia and Gansu (Kansu). Vert PalAsiat, 17: 222-235

Qiu Z X, Wang B Y, Xie G P, 2000. Preliminary report on a new genus of Ovibovinae from Hezheng District, Gansu, China. Vert PalAsiat, 38: 128-134

Rodler A, 1889. ÜberUrmiatherium polakin. g. n. sp., einen neuen Sivatheriiden aus dem Knochenfelde von Maragha. Denkschriften der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Math-Naturwiss Kl, 56: 315-322

Schlosser M, 1903. Die fossilen Säugetiere Chinas nebst einer Odontographie der recenten Antilopen. Abh Bayer Akad Wiss II, 22: 1-221

Shi Q Q, 2014. The second discovery ofTsaidamotherium(Bovidae, Artiodactyla) from China, with remarks on the skull morphology and systematics of the genus. Sci China Earth Sci, 57: 258-266

Shi Q Q, He W, Chen S Q, 2014. A new species ofShaanxispira(Bovidae, Artiodactyla) from the upper Miocene of China. Zootaxa, 3794: 501-513

Sickenberg O, 1933.Parurmiatherium rugosifronsein neuer Bovide aus dem Unterpliozän von Samos. Palaeobiologica, 5: 81-102

Xue X X, Zhang Y X, Yue L P, 1995. Discovery and chronological division of theHipparionfauna in Laogaochuan Village, Fugu County, Shaanxi. Chin Sci Bull, 40: 926-929

Zhang Z Q, 2003. A new species ofShaanxispira(Bovidae, Artiodactyla, Mammalia) from the Bahe Formation, Lantian, China. Vert PalAsiat, 41: 230-239

甘肃临夏盆地首次发现乌米兽(牛科,偶蹄类)头骨化石

史勤勤1王世骐1陈少坤1,2,3李刈昆1,2

(1 中国科学院脊椎动物演化与人类起源重点实验室,中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所 北京 100044)

(2 中国科学院大学 北京 100039)

(3 重庆三峡古人类研究所,重庆中国三峡博物馆 重庆 400015)

报道并描述了一件来自甘肃临夏盆地的中间乌米兽(Urmiatherium intermedium)头骨化石新材料,该材料产自柳树组上部,属于晚中新世晚期杨家山动物群。中间乌米兽是一种大型的晚中新世牛科动物,角心特化,短且呈薄板状,并且在基部相互靠近。在角心前后方的额骨和顶骨上,发育大片赘生骨疣,这些骨疣与角心一起,合称角器。20世纪初,步林报道了中国北方晚中新世地层中的大量中间乌米兽化石,包括产自山西保德和甘肃庆阳的20多件头骨以及很多破碎的齿列和骨骼。本文报道的乌米兽头骨化石是乌米兽在甘肃临夏盆地的首次发现,将其在中国北方的分布向西扩展到了青藏高原东北缘地带。乌米兽被普遍认为与近旋角羊(Plesiaddax)、和政羊(Hezhengia)和柴达木兽(Tsaidamotherium)等晚中新世“麝牛类”牛科动物具有较近的亲缘关系,但其系统发育地位仍存有争议。相比其他晚中新世“麝牛类”牛科动物,乌米兽的分布较广,从伊朗至中国北方都有分布,但它鲜与其他晚中新世“麝牛类”牛科动物伴生。在临夏盆地,与其伴生的牛科动物目前仅发现中华羚(Sinotragus)一种。

临夏盆地,晚中新世,牛科,乌米兽

Q915.876

A

1000-3118(2016)04-0319-13

2015-10-22

Shi Q Q, Wang S Q, Chen S K et al., 2016. The fi rst discovery ofUrmiatherium(Bovidae, Artiodactyla) from Liushu Formation, Linxia Basin. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 54(4):319-331

国家自然科学基金重点项目(批准号:41430102)、国家重点基础研究发展计划项目(编号:2012CB821906)和国家自然科学基金青年科学基金项目(编号:41402020)资助。

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

古脊椎动物学报(中英文)的其它文章

- A new microraptorine specimen (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae) with a brief comment on the evolution of compound bones in theropods

- Sciurid remains from the Late Cenozoic fi ssure- fi llings of Fanchang, Anhui, China

- A skull of Machairodus horribilis and new evidence for gigantism as a mode of mosaic evolution in machairodonts (Felidae, Carnivora)

- 陕西洛南龙牙洞小哺乳动物化石新材料

- On the geological age of mammalian fossils from Shanmacheng, Gansu Province