绅士做派,大有来头

2016-02-03

Do you ever wonder why we gentleman do the things we do? In some cases, understanding where our cultural norms come from can give us a renewed appreciation for them. In other cases, it just makes for fun trivia1). Either way, we hope you'll find these historical tidbits2) as interesting as we do.

你曾好奇过为什么我们绅士会有我们特有的做派吗?有时,了解我们的文化规范起源于何处能让我们从新的角度欣赏它们。而在其他时候,这正好可以成为有趣的小知识。无论怎样,我们希望你会像我们一样觉得这些历史趣闻有意思。

Why do we escort3) women on our left arm?

When a man escorts his partner, tradition has it that he offers his left arm. This tradition originates from medieval times when men escorted women around town and through the fields. Should a threat arise or the woman's honor require defending, the man's sword hand (his right hand) would be free, giving him quick and easy access to his sword, worn on his left side.

To this day, the left arm rule still applies while indoors. However, with the rise of wheeled vehicles and non-pedestrian streets, the proper escorting etiquette4) evolved over the years for outdoor environments. Today, when escorting a women outdoors, you should position yourself on the outside (closest to the street) to protect her from traffic, mud splashing, etc.

为什么我们用左臂护送女伴?

当一位男士护送他的女伴时,按照传统,他要伸出左臂。这一传统起源于中世纪,那时女士在镇上四处走动或在田野中穿行时会有男士护送。万一有危险发生或者需要维护女伴的荣誉,男士惯于用剑的手(他的右手)将是空闲的状态,这样就能让他立马轻松抽出佩戴在身体左侧的剑了。

直到今天,用左臂护送女伴的规则在室内仍然被沿用。但是,随着有轮交通工具和非步行街的兴起,户外环境下护送女伴的适宜的礼仪这几年也有所演变。如今,在室外偕女伴而行时,你应该让自己处于外侧(离街道最近),以便保护她与来往的车辆和四溅的泥水等隔开。

Why are the bottom buttons of our suit jackets

and blazers5) never to be fastened?

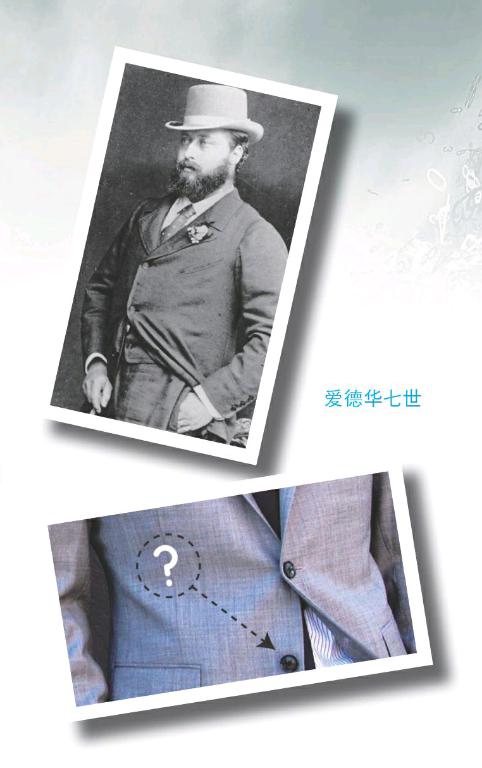

This fashion guideline is typically attributed to King Edward VII, the British monarch from 1901 until his death in 1910. Quite the gourmand6), King Edward loved his food so much that the royal tailors often had trouble keeping up with his ballooning figure. One day, seeking reprieve7) from the confining constriction of his waistcoat8), King Edward casually unbuttoned the bottom button. At that time, the King set the fashion trends and when members of his court saw his new look, they quickly emulated9) it. The fad10) spread like wildfire and within weeks unbuttoned bottom buttons were found everywhere.

We continue to honor the memory of Edward the Wide to this day. Modern suit jackets and blazers are actually designed to cutaway at the hips with the bottom button left undone. Buttoning it results in unsightly11) pulling and bunching of fabric12) at the waist and disapproving looks from your fellow gentlemen.

为什么我们的西装外套和轻便夹克最下面的

那颗扣子从来不扣?

这一时尚指南通常要归功于英王爱德华七世(在位时间从1901年到1910年去世为止)。爱德华国王是个十足的美食家,他对食物非同一般的喜爱让皇家御用裁缝做衣服的速度经常难以赶上他不断发福的身材。一天,为了从马甲过紧的束缚中求得放松,爱德华国王随意地解开了最下面的那颗扣子。在那个年代,国王就是流行风尚的发起者,当一些朝臣看到国王的新装扮,他们便迫不及待地开始模仿。这股风潮像野火一般扩散开来,没出几周,便处处可见人们解开外套最下面的那颗扣子。

我们一直到今天都还在表示对身宽体胖的爱德华国王的纪念。实际上,现代西服外套和轻便夹克的前下摆在髋部是设计成圆角的,最下面那颗扣子是解开的。如果你扣上了,腰部的布料会绷紧打褶,非常不雅观,你的绅士同伴们也会露出不悦的表情。

Why do we give toasts?

In ancient Greece, being poisoned was a real and constant fear. In order to allay13) this fear, at a party, the host would pour wine for his guests and then take the first drink and toast everyone to show that the wine was safe to drink. Incidentally, the term "toast" also comes from this tradition. Toasting is a reference to the toasted bread that ancient Greeks dipped into their wine to cut the acidity14).

我们为什么要敬酒?

在古希腊,被人下毒是一种真实存在且不断发生的令人恐惧的事情。为了解除这种恐惧,在聚会上,主人会为宾客们倒酒,然后自己喝下第一口,再向每个人敬酒,以示酒可以安全喝下。巧合的是,“toast (敬酒)”这个词也来源于这一传统。“Toasting”指的是古希腊人吃的烤面包,为了减少酸味,他们吃面包时会蘸酒。

Where did the custom of removing or tipping a hat as a sign of respect come from?

In medieval times, knights often encountered each other in full armor making it difficult to distinguish friend from foe. As a sign of friendliness, knights would lift their helmet visors, showing their faces to one another. The custom of tipping ones hat to another, as a symbol of politeness, is a direct descendant of this medieval practice. Interesting note: the modern military salute shares the same origin.

摘下帽子或轻触帽子以示尊重这一习俗是从哪儿来的?

中世纪时期,骑士们遇到彼此时常常都是全副武装,这让他们很难分清敌友。作为一种友好的示意,骑士们会抬起头盔上的面甲,互相让对方看清自己的脸。冲着他人轻触帽子作为一种礼貌的标志,正是直接从这一中世纪惯例演变而来。有趣的一点是:现代军队的敬礼也起源于此。

5. blazer [?ble?z?(r)] n. 轻便夹克

6. gourmand [?ɡ??m?nd] n. 美食家

7. reprieve [r??pri?v] n. (痛苦、烦恼等的)暂减;暂时缓解

8. waistcoat [?we?sk??t] n. 马甲

9. emulate [?emjule?t] vt. 模仿

10. fad [f?d] n. 一时的风尚

11. unsightly [?n?sa?tli] adj. 难看的

12. fabric [?f?br?k] n. 织物

13. allay [??le?] vt. 解除(忧虑、苦痛、疼痛等)

14. acidity [??s?d?ti] n. 酸味

15. overtly [???v??tli] adv. 公开地

Why do we give flowers to communicate our feelings of love, friendship, grief, sympathy and congratulations?

In the 1700's, Charles II of Sweden returned from Persia, bringing with him the custom of "the language of flowers" to Europe. Different flowers communicated different sentiments or meanings to the point that entire conversations were carried out through the sending and receiving of flower bouquets. Today we usually communicate our intent overtly15) with an attached note or card but the custom of sending flowers endures.

为什么我们要通过送花来表达爱、友谊、悲伤、

同情和祝贺这些情感?

在18世纪,瑞典国王查尔斯二世从波斯归来,把“花语”这样的风俗也带到了欧洲。当时,不同的花表达不同的感情、传递不同的信息,甚至到了整个对话都完全能通过收送花束来进行的程度。今天,我们常常通过附上留言条或卡片来公开地表达我们的意图,但送花的习俗一直保留了下来。