Gods of Change

2016-01-10刘莎

刘莎

Chinas ethnic deities now face a more subtle threat: tourism

民俗風情旅游催生了盛大的传统庆典和仪式,古老的神灵是喜还是忧?

Like all ancient peoples, the Chinese anthropomorphized the turns of the seasons and the ways of the heavens with stories and fables.

This is the way gods are born.

Attempts to explain the laws of nature and physics were overseen by gods and goddesses—everything from basic elements like water, fire, and light to aspects closer to ourselves, animals like cattle, butterflies and frogs, as well as ancestors who became omniscient saints. Today, China has a population of 1.3 billion people and 90 percent are Han Chinese; the remaining ten percent, made up of 55 ethnic groups, are remembered, in part, through their deities—but not the way one might imagine.

These traditional gods may have had, one might argue, a bit of a promotion in the pantheon department in recent years. Indeed, these gods and heroes have been rented out by the authorities who promote them as a symbol of unity and an important tool to promote folk culture and develop the tourism industry.

For example, you have the Guzang Festival (鼓藏节) of the Miao ethnic group, who mainly live in Guizhou and Hunan provinces. According to one version of their legend, 12 different species were bred from a butterfly goddess in the form of eggs, including humans. The butterfly goddess failed to hatch one of her sons: a buffalo. She then asked a storm to smash the egg to release the buffalo. When the buffalo grew up, he hated the butterfly mother for not hatching him in person and the butterfly mother died of a broken heart. The buffalo, in turn, refused to help the farmers grow grain, so the other 11 siblings united to kill the buffalo—revenge for the death of the butterfly mother. Afterward, cattle worked on farms as beasts of burden.

As a result, the Miao people started to sacrifice their buffalo to honor the butterfly goddess in the hopes of a good harvest to come. According to tradition, every 12 years or so, a grand ceremony was held and during the approximately week-long festival, people sacrificed buffalo, danced, and refused to eat vegetables, speaking only in the Guzang language and eating steamed sweet sticky rice and pig feet.

Today, the festival has omitted the no-vegetable rule, and the six-day festival has turned into a more manageable two-day annual event, filled with more dancing and singing rather than solemn buffalo sacrifice. This way tourists can get a holiday dose of this unique ethnic tradition. In the meantime, many villagers take the opportunity to start their small businesses to make money—acting as dancers and singers or selling hand-made products as vendors.

But some people think such folk culture tourism has lost its roots. “Obviously, younger Miao people know that the butterfly goddess thing is made up, so they use this festival as something to make money rather than keeping a sacred attitude,” says Mu Yiyun, a travel columnist based in Shanghai who has traveled to many ethnic areas.

Mu says that the handicrafts sold in Guzang Festival are similar to what he sees in other places: factory-made souvenirs like crystal beads, inscribed silver bracelets, knitted baskets, and other tat that can be bought at the local airports and souvenir shops.

“Ive been to many god-worshipping ceremonies; at nearly every festival, embedded with ancient belief or not, people dance and sing in groups but sometimes they dont look like theyre enjoying it and just perform to entertain the tourists,” he says.

Once the ritual becomes entertaining, the core of the culture is weakened, says Feng Jicai, a famous writer and the vice-president of the Chinese Folk Literature and Art Association, adding that the effect it has on the local economy is undeniable.

But, when one considers the barbarity that many ethnic cultures faced in Chinas recent history, can it really be that bad? Or, rather, can a free market truly accomplish what was started in those bygone years of cruelty? Chinese culture suffered during ten years of Cultural Revolution. Some ceremonies and festivals honoring gods were deemed as “superstitious” and “anti-scientific”, and many religious customs were damaged.

Traditionally, every first month of the lunar calendar, the Zhuang ethnic group hosts the Wapo Festival (蛙婆節), meaning “frog goddess festival” to honor their frog goddess in charge of farmland in the hopes that it will bring a better harvest.

The festival originated in the Donglan County of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, where the Zhuang, the largest ethnic group among Chinas 55 ethnic minorities, gather. It is said that a frog was sent by Heaven to Earth to rule over farmland and harvests, but a farmer, annoyed by the croaking sound of frogs, poisoned all the frogs on his land. Not a single grain was reaped in the whole village that year. People realized that killing frogs displeased the frog goddess so they retrieved every murdered frog and gave them a proper burial ceremony.

During the austerity of the Cultural Revolution, the idea of going out to find frogs to sing and dance around was considered to be “offending public decency.”

But, today, the festival is back with government approval.

Today, inclusion is the watchword, with ethnic dances at the Spring Festival Gala and Dai songs taught in primary schools—as well as a healthy dose of funds for research and preservation from the central government.

Developing ethnic tourism has been addressed as far back as national policy in 1980, and the strategy of developing tourism in ethnic areas has been mentioned in almost every years Ethnic Affairs Work Conference, a meeting for ethnic affairs chaired by top Party leaders. For some remote and poverty-striken area governments, developing folk culture has been an important incentive to drive GDP.

Buluotuo (布洛陀), said to be the creator of ethnic cultures in the Pearl River Region, was viewed as a sacred figure of the Zhuang ethnic group and the annual honoring ceremony has evolved into the Buluotuo Folk Culture Tourism Festival, which takes place in Tianyang County, Baise, Guangxi.

In 2013, the three-day holiday in March attracted over 450,000 tourists and made a whopping 46 million RMB, the Baise News Online reported—not a bad haul for an ethnic god.

Tourists are invited to join locals in climbing a mountain and worshiping Buluotuo; tourists also participate in games with Zhuang features like bullfighting and throwing embroidered balls, none of which were included in the traditional worship ceremonies.

Yue Xiulian, a staff member at the Baise Tourism Bureau, told TWOC that the three-day festival helped people understand their culture and provided chances for the locals to sell travelers handicrafts and native specialties like tea and tea oil.

“For Zhuang villagers living in Tianyang, this festival takes more effort to prepare than the Spring Festival. Some families prepare stuff to sell in March in the winter,” Yue says. She does not think the commercial atmosphere damages the sacred worship ceremony. “The wealth is brought to us by Buluotuo and he would not mind villagers getting rich while honoring him at the same time.”

Similarly, Southwest Chinas Guizhou Province, with 17 different ethnic minorities, holds over 1,000 such festivals related to ethnic beliefs a year; from January to December tourists can find themselves accidentally bumping into such ethnic rituals and festivals every time they turn a corner.

The Guizhou provincial government has invested over 100 billion RMB over six years in developing ethnic tourism, which it claims bolsters ethnic culture and helped over 420,000 local people out of poverty, according to a tourism department report in 2013.

The construction of related infrastructure—museums, theme-parks, hotels, restaurants, and exhibition centers—has developed a prosperous tourism industry, the report claims.

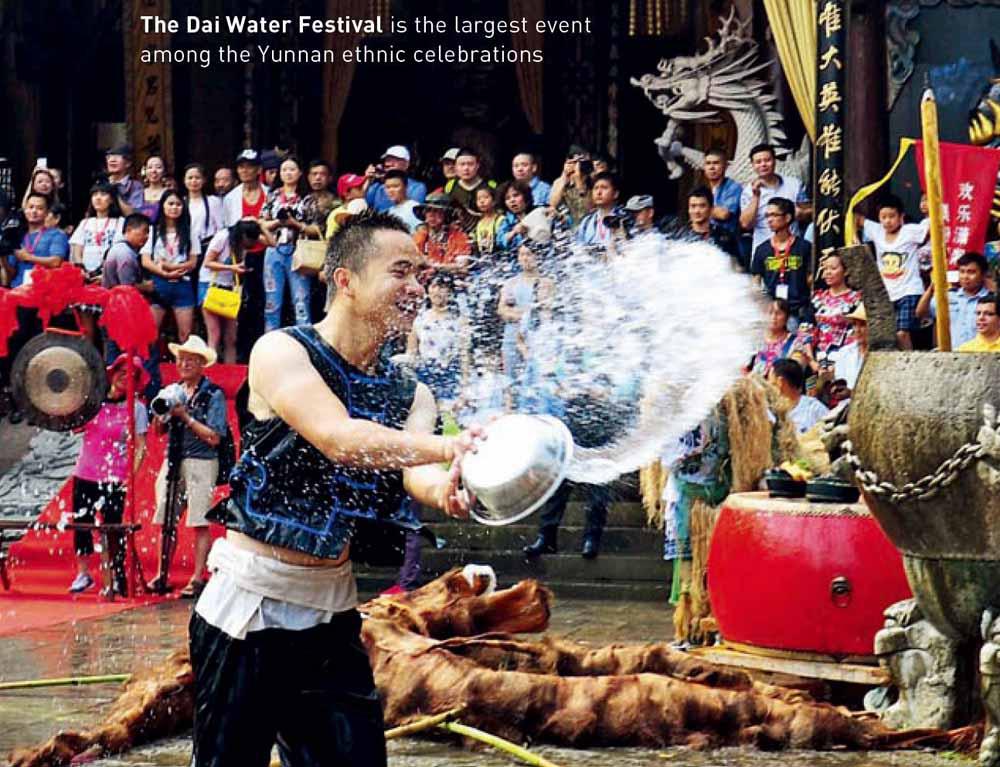

However, if you want to be a god in modern times, it helps to be fun; this is perhaps no more evident than with the Dai water festival. Poshuijie (泼水节), or the Dai Water Festival, has become the largest carnival of all the Yunnan ethnic groups. Its fun and easy to understand: water is cleansing, so if you like someone, splash them. This quasi-religious festival often just turns into a carnival and has been accused of losing its true meaning.

There is a price for keeping the austerity of old. In Yongzhou, Hunan Province, local people hold public rituals to worship Emperor Shun (舜帝陵), a legendary Han leader, whose tomb is in Jiuyi Mountain. There is no singing or dancing or localized food tasting, just ceremonial speeches and sight-seeing in the heritage park. Even though Emperor Shun is a very mainstream saint for Han Chinese, the number of participants only reaches about 10,000 each year.

The Yi ethnic group, scattered throughout Yunnan, Sichuan, and Guizhou, believe in a god of fire, which they celebrate every year in July with the Huobajie (火把節), or Torch Festival, where people dance and sing around fire. According to Yunnan Tourism Department data, at least 30,000 people, tourists as well as nearby ethnic groups like the Naxi and Bai, participate.

Over 50 percent of ethnic people in China are believers in folk religions. But not every ethnic tradtion is suitable for tourism.

Tibet is a place full of mystery and charm and the Tibetan sky burial is perhaps the most mysterious of the varied traditions of the region. The sky burial is a funeral practice more than a 1,000 years old, abandoned only briefly during the Cultural Revolution. During the ritual, human bodies are dismembered by burial masters and fed to vultures and other predatory birds. In Tibetan Buddhism, such burials are seen as a final devotion to the divine creatures of earth, and, without a body, their soul will ascend.

The process is supposed to be solemn and peaceful, but curious tourists talking, taking photographs, and moving around have disrupted the once common ritual and upset the grieving families. Travel blogs and agencies blithely describe how “shocking” the burial is and how it is a “must” for travelers in Tibet.

Before Tibetan lawmakers formally passed a law in January 2015 protecting the ceremony, the regional government issued three provisional rules banning tourists from watching or photographing the ritual.

“It shows respect and offers protection to the millennium-old tradition,” Samdrup, a regional lawmaker, told Xinhua News Agency when the law passed.

Over 60 percent of Tibetan believers are said to choose such a burial, and none of them believe it is a performance for tourists. While these types of festivals bring much needed money to often poor regions, it is a question of priorities.