BEHIND PALACE WALLS

2015-11-05ByYuanYuan

By+Yuan+Yuan

‘Whats to do? Shall we go see the reliques of this town?”This quote, taken from playwright William Shakespeares Twelfth Night, was the idea many history enthusiasts had on October 10, as visitors crowded the gates of Palace Museum in the heart of Beijing. Yu Jian, a 35-year-old businessman from Zhengzhou, central Chinas Henan Province, came all the way to Beijing, three and a half hours by express train, on October 10 in the hopes of visiting an exhibition of ancient calligraphic works and paintings at the Palace Museum in the heart of Beijing. To be more specific, he traveled far and wide to view the painting Along the River During Qingming Festival, a masterpiece dating back to the Song Dynasty (960-1279) that he has yearned to see for years.

The last time the painting was shown to the public was 10 years ago. “At that time, I was still a young man and didnt get detailed information about that exhibition,” Yu said. “Now I wont miss my chance.”

The Palace Museum opens at 8:30 a.m., and Yu arrived at the gate just before 9 a.m. on October 11. But he was told by the museums staff that he had to wait a minimum of 10 hours in line to see the famous painting that he admires.

Obviously, Yus goal was the goal of countless others. “I thought I was early, but the line stretched from the entrance all the way down to the Wuying Hall, where the painting is on dis- play and is several hundred meters away from the gate,” he said.

Compared to other visitors, whose painting vigil outside the Palace Museum began at 4 a.m., Yu was tardy. Xu Xiaolu, a sophomore student from Beijing Normal University, arrived at the gate around 5:30 a.m., but there were already many people waiting in front of her.

“I knew what the situation would be like because some visitors shared pictures of the long waiting line online,” Xu said. “I got up at 4:30 a.m., but it seems I was still late.”

Massive draw

The exhibition that has attracted the crazy long line is the Masterpieces From the Qing Imperial Catalogue The Precious Collection of the Stone Moat, considered to be the royal catalogue of calligraphy and paintings. It opened on September 8 as part of celebrations for the 90th anniversary of the founding of the Palace Museum.

The masterpieces were successively compiled during the reign of Emperors Qianlong (1736-96) and Jiaqing (1796-1821) of the Qing Dynasty by 31 officials under imperial command.

They selected more than 10,000 of the finest paintings and calligraphy samples from the imperial collection of the Qing court.

The Palace Museum selected more than 100 art pieces from the precious collection for the 90th anniversary display.

“The items are all remarkable historical pieces. It is such a great opportunity to have so many treasures displayed together,” said Zeng Jun, Director of the Palace Museums Calligraphy Department. “The whole scroll of the painting Along the River During Qingming Festival, the highlight of the exhibition, will be shown for one month at this exhibition, and people wont be able to see it again in at least three years.”

The painting depicts the city of Bianjing(modern-day Kaifeng in Henan) and people from all walks of life in exquisite detail. It is a window into the world of prosperity then present in Bianjing and the economic power of the northern reaches of the Song Dynasty.

The superb skill of the artist, the grand scale of the scene and the historical and cultural value of this painting make it a national treasure. Even high-end copies can sell for several million yuan in the art market.

Along with the paintings and calligraphies, items from Ru kiln produced in the Song Dynasty, have also been displayed for the celebration.

With a light sky-blue glaze, an elegant shape and the great difficulty involved in its firing, the Ru kiln was ranked first among the five great kilns by later generations. In those days they were produced exclusively for imperial use.

“The Song Dynasty is my favorite dynasty in Chinas history,” said Zhang Yi, a movie maker at the exhibition. “It is the dynasty for the arts, and I want to make a movie about this dynasty, as well as the awesome porcelain.”

The enthusiasm for Along the River During Qingming Festival far exceeded the expectations of Zeng. After all, the painting had been shown before. “It was not the first time the masterpiece was on display at the Palace Museum,”he said. “Ten years ago, at the 80th anniversary of the museum, we also exhibited it, but there were far fewer visitors at that time.”

However, considering the sharply increasing number of visitors in recent years, the“Palace Museum fever” may be less inexplicable than it seems at first glance. Seven million visitors came to the Palace Museum in 2002. That number rocketed in 2014, more than doubling to 15.34 million. For a further comparison, October 1, 2005, marked a previous record for Palace Museum visitors—a number a little over 56,100. On October 2, 2012, more than 182,000 visitors swarmed the museums halls, setting the highest record ever.

The visitor numbers were so high that the Palace Museum had to take action to control the admission of tourists. Since 2014, the museum has closed on Mondays for renovation and maintenance work, and since June 13 this year, visitors have been limited to 80,000 daily. On this past October 2, the 80,000 tickets were sold out shortly after the doors had opened, and all ticket windows were shut down at 10:10 a.m.

Piece of history

The Palace Museum is housed in the Forbidden City, an ancient imperial complex, in downtown Beijing. Now, those two names refer to the same place. In 1987, the Forbidden City was included in the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organizations World Cultural Heritage list.

As home to most emperors of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and all emperors of Qing dynasty (1616-1911), the Forbidden City witnessed royal family intrigue and turmoil from 1420 to 1911. Following the Revolution of 1911, which ended the reign of the Qing Dynasty, the last emperor, Puyi, remained in the complex until 1924.

After Puyi was expelled, a special committee was formed by the then national government in 1925 to catalog the artifacts. On October 10, the Palace Museum was established and survived wars and social unrest in the coming years.

From 1933 to 1945, the museum was on the road for 12 years during the Chinese Peoples War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. The majority of items—19,600 crates of treasures—traversed the country, from Beijing to Nanjing in Jiangsu Province and then other safer places further inland.

In 1948 and 1949, the Kuomintang authority led by Chiang Kai-shek fled to Taiwan and shipped 2,972 crates containing national treasure there, where it built the “National Palace Museum” in 1965, resulting in the two Palace Museums today.

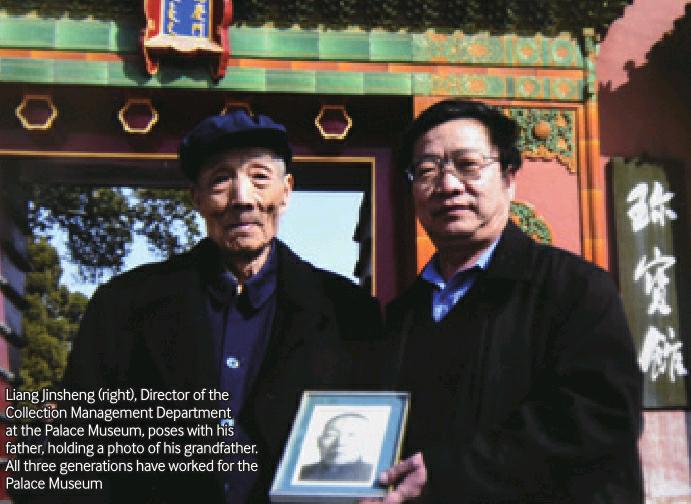

Liang Jinshengs grandfather Liang Tingwei was among the team protecting the transferred collections of the Palace Museum from 1933-45. During the years, the whole family moved with Liang Tingwei to many places in the country. In 1949, Liang Tingwei went to Taiwan with some family members, and Liang Jinsheng, who was only 1 year old at that time, came back to Beijing with his father.

This temporary separation of the family turned permanent. Liang Tingwei passed away in Taiwan in 1972. In 2008, Liang Jinshengs father passed away as the last person that witnessed the odyssey of the ancient items of the Palace Museum.

Liang Jinsheng spent his childhood mostly in the Palace Museum, where his father worked, mainly collecting artifacts that were geographically scattered by war.

In 1979, Liang Jinsheng also started his work in the museum. Now, he is director of the Collection Management Department at the Palace Museum.

“It is an honor to follow the footsteps of older generations,” said Liang. “My grandfather transferred national treasures out of Beijing during the war, while my father was responsible for putting them back. Now, I am in charge of putting them in order.”

Doors to the future

Realizing the significance of keeping the collection together, in 2004, Zheng Xinmiao, Curator of the museum between 2002 and 2012, began the long process of organizing and arranging display items logically. After more than six years, thousands of artifacts had been sorted, giving an exact count of the items in the Palace Museum—1,807,558.

“This number is the result of years of hard work from 2004 to 2010,” said present curator Shan Jixiang.

Among the 1,807,558 items, there are 53,482 paintings, 75,031 works of calligraphy, 159,734 items of copper, as well as 603,000 ancient books and documents, 367,000 pieces of porcelain and 11,000 sculptures, some of which date back to the Warring States Period (475-221 B.C.).

Its an overwhelming amount of history. “If we display 18,000 items each year, well need 100 years to show all the items in the museum,” said Shan.

On October 11, four new sections in the Palace Museum were opened to tourists for the first time, making 65 percent of the complex accessible to the public.

“We opened more areas to allow the public to see more of the Palace Museum,” said Shan. “In 2002, only 30 percent of the Forbidden City was open. In 2014, it expanded to 52 percent. In 2020, at the 600th anniversary of the Forbidden City, we will open more than 80 percent of the complex.”

For Shan, many visitors now still view the Palace Museum as a tourist destination, especially in recent years with the rising popularity of the TV series on the ancient royal life in the Forbidden City, such as The Legend of Zhenhuan.

“Those plays are fictitious,” Shan said.“Museums are more for education. I hope, in the future, our museum can show an authentic and original picture of ancient life here.”

Shan, appointed to head the Palace Museum early in 2012, has worn out more than 20 pairs of traditional cloth shoes patrolling the 9,000 rooms of the Forbidden City. He runs a tight ship.

“We have taken thousands of photos of buildings and other trivial things. Whenever we find something wrong, we show the pictures to the staff, which has made them much more alert to encroaching imperfections.”

To make the time-honored Palace Museum more fashionable and accessible to the young and educated, Shan has been responsible for a number of recent products, such as the museums mobile app, which shows the museums items in great detail and with 3D effects.

A public account of the Palace Museum called Micro Palace Museum was launched on social networking app WeChat in 2012, releasing exhibition information and introducing masterpieces with cartoons and humorous expressions.

An online shop, registered in 2010 on the leading online shopping website Taobao.com, also made available odds and ends with cartoon characters like ancient princes and princesses.

“Integrity is the key to a sustainable and fascinating museum,” Shan said. “I hope that we can maintain the integrity of the museum for another 90 years.”