AID MATTERS

2015-08-18ByYinPumin

By+Yin+Pumin

After obtaining 100,000 yuan($16,100) in earnings owed from the construction company he had worked with for more than five years, Chen Xing—a migrant worker from southwest Chinas Guizhou Province—appeared somewhat emotional.

“I didnt expect I would receive the back pay so soon considering past examples,”Chen said, expressing his surprise at the efficiency of the legal aid service he received from the Xiaoshan District Legal Aid Center in Hangzhou, capital of east Chinas Zhejiang Province.

After failing to receive earnings from his boss for more than two years, Chen decided to resort to the legal process in 2014 to gain redress.

“I had never heard about legal aid services before, so I originally planned to solve the problem through a lawsuit, but the duty lawyer from the Xiaoshan District Legal Aid Center changed my mind,” Chen said. “He analyzed my case and told me that, as a migrant worker, I could apply directly for free legal assistance from his center without undergoing investigation.”

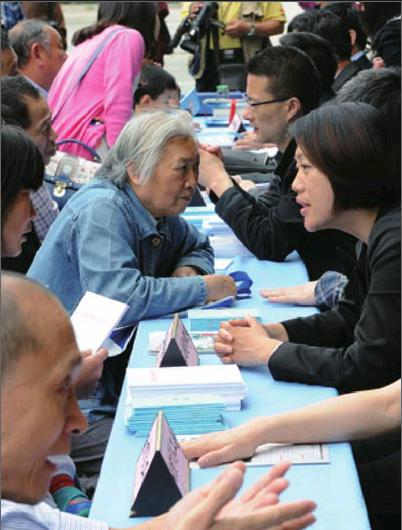

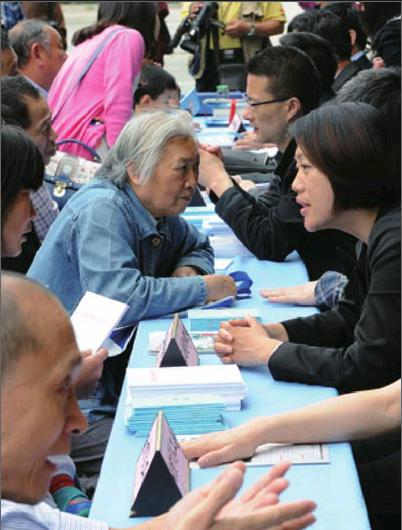

Chen was one of more than 1 million people who received free legal aid services last year. Ministry of Justice figures show that national legal aid departments under local justice authorities concluded 1.24 million legal aid cases in 2014 and offered legal aid to 1.39 million people, a 9-percent increase year on year.

Legal aid is a means by which parties who are experiencing economic hardship, or involved in special cases, may get legal assistance in the form of a reduction or exemption of the service fee provided by the state, according to the website of the Ministry of Justice.

The legal aid system, with its essence of state duty and government action, is important in implementing the constitutional principle of“All citizens are equal before the law.” It guarantees that all citizens enjoy equal and impartial protection under the law to perfect social insurance systems and complete the human rights protection mechanism.

To keep pace with Chinas social and economic development, the government started developing a legal aid system with Chinese characteristics in 1994. With the successive promulgation of Criminal Procedure Law and Law on Lawyers in 1996, the legal aid system was granted its status in the Chinese judicial system.

In 2001, the 10th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development(2001-05) made developing a legal aid system a goal of social development. On September 1, 2003, the Regulations on Legal Aid took effect, stating the governments duty to provide legal aid.

“The formal promulgation and implementation of the regulations symbolized a new historical development period of our countrys legal aid work, from the establishment of the system to its rapid expansion,” said Sun Jianying, Director of the Legal Aid Department at the Ministry of Justice.

Figures from the ministry show that the nations legal aid departments have concluded 7.5 million cases and offered legal assistance to about 9 million people since 2003. Last year, legal funding reached 1.7 billion yuan ($277.32 million), an increase of 4.8 percent.

The system boasts 3,700 legal aid centers across the country, with 14,000 lawyers offering free legal services, ranging from consultation to representation in criminal cases or mediation in civil disputes, according to the ministry.

However, with the public becoming increasingly aware of their legal rights, more and more people are turning to legal aid, and the existing system has become inadequate.

“As China transforms its political and economic growth model, various kinds of social conflicts are rising sharply, putting the interests of vulnerable groups at risk,” Sun said.

“In China, many victims are poor and cant afford to hire a lawyer for a lawsuit or ask for a legal consultation. But if small disputes cant be solved in a timely manner, they will probably lead to bigger social conflicts or mass incidents,” Sun added.

The State Council, Chinas cabinet, issued on June 29 an instruction on improving the legal aid system in order to expand the scope of legal aid to protect the rights of vulnerable groups.

Legal aid services will be extended to migrant workers, the elderly, women, minors and the disabled to ensure justice and social fairness, according to a notice issued by the Ministry of Justice.

“Apart from the vulnerable groups, free legal aid will be extended to those involved in civil disputes and criminal cases involving peoples livelihoods, such as marriage and family, food safety, education and healthcare,” said Vice Minister of Justice Zhao Dacheng.

In addition, people with low incomes and those who cant hire lawyers will be eligible for free legal aid, he said.

These moves were a response to a key meeting hosted by President Xi Jinping in May, where legal aid was viewed as an important livelihood project, and the protection of peoples rights and interests should be taken as the new start and end points.

“The purpose of improving legal aid is to expand the scope of free aid services and improve its services so that eligible people will get legal aid and have equal access to justice,” Xi said.

Expanding the scope

“One of the core highlights of the June instruction is the extension of the scope of free legal aid services,” said Chen Guangzhong, Honorary President of the Procedural Law Research Institute at China University of Political Science and Law (CUPL).

The Ministry of Justice started its research work early in 2014, according to Vice Minister of Justice Zhao.

In June, the final instruction listed detailed measures on perfecting the legal aid system. The extension of the scope is embodied in three aspects: extending the coverage of legal aid services to civil and administrative cases; extending coverage of groups with economic difficulty; and realizing the universal coverage of legal aid counsel services.

“The most striking aspect is the extension of the coverage on civil and administrative legal aid services. In the Regulations on Legal Aid, and even in the latest-revised Civil Procedure Law, there are no specific contents on civil and administrative legal aid services. The June instruction makes up for that oversight,” Chen Guangzhong said.

In addition, he also recognized the lowering of the threshold to legal aid services. “The lowering of poverty standards will greatly enlarge the scope of legal aid services and benefit more groups in need,” he said.

The instruction identified key social groups to be covered by legal assistance, including rural migrant workers, those who have been laid-off, the elderly and the disabled.

The existing coverage of legal assistance includes helping citizens with financial difficulties apply for state compensation, basic living allowance, claim payment for their work, and other issues.

Legal assistance will also benefit more people facing criminal charges in order to play a greater role in defending human rights, said the instruction. Such services will also be offered to those who intend to appeal but lack the financial means.

Moreover, Zhao added that free legal assistance was available for anyone in China, including Chinese from territories outside the mainland, for non-contentious matters, and also available for foreign defendants appearing in Chinese courts.

Another measure listed in the instruction broadens peoples access to legal aid. According to Sun at the Legal Aid Department of the Ministry of Justice, the ministry is planning to set up more legal aid offices in local detention houses and courts.

To date, more than 1,500 legal aid offices have been established in detention houses in the country, and the ministry will set up local legal aid offices in pilot courts to offer legal consultation to the parties involved in appeal cases, she said.

People with mobility problems, such as the elderly and the disabled, can use the hotline 12348 or the websites of local legal aid departments. The hotline and websites have proved to be effective points of access to legal aid. According to ministry statistics, 6.8 million people applied for legal assistance last year and most of them sought consultations through the websites or the hotline.

In Jiangsu and Hubei provinces and Beijing, justice departments regularly publicize legal aid information on their microblog or WeChat accounts. Designated lawyers also offer legal consulting on these social media platforms, Sun said.

Li Xuelian, a senior official at the ministrys Legal Aid Department, said 80 percent of the cases calling on legal aid services related to civil issues, such as payment and employment disputes, marriage and domestic affairs, as well as traffic accidents. The others involved criminal cases and administrative litigation.

The extension of the scope of legal aid services raises a new question: Can various guarantees, especially financial ones, catch up with the development?

“Without guarantee mechanisms, the extension of the scope and the improvement of the quality of legal aid services will be impossible to realize,” Chen Guangzhong said.

“We are facing great pressures in legal aid funding and personnel, especially after the implementation of the new Criminal Procedure Law, which will see more criminal legal aid cases,” Sun said.

The instruction anticipated the question and outlined measures to provide guarantees, directing governments at all levels to include legal aid into their budget and specifying that the funds must be used exclusively for the designated purpose of legal aid, mainly to cover the cost of case-handling and the subsidies for lawyers.

According to a report by Xinhua News Agency, over 9 percent of counties have yet to include legal aid in their annual local government budgets.

Tong Lihua, Director of the Beijing Childrens Legal Aid and Research Center, suggested private legal firms and other social institutions should be encouraged to participate in legal aid.

China has established five legal aid foundations, including the China Legal Aid Foundation and the Beijing Legal Aid Foundation, to accept and manage endowments from home and abroad to support public welfare organizations in the provision of free legal assistance to citizens, according to the Ministry of Justice.

Improving services

The June instruction also proposed improving the quality of legal aid services, stating that the central authorities will devote greater efforts to exploring suitable development models to cultivate more professional legal aid personnel.

Tong believes the cultivation of legal aid personnel is the key to improving quality.“Professional lawyers and other workers are the guarantee of quality legal aid services,” he said.

According to Tong, only about 5,000 lawyers are devoted specifically to legal aid work across the country. “Besides the small number, the level of their professionalism is also much lower than market-oriented lawyers,” he said. Tong proposed outsourcing such jobs and encouraging social organizations to help things in this regard.

Chen Guangzhong at CUPL also admitted that low professionalism of legal aid lawyers has led to the low quality of Chinas legal aid services.

“One of the main problems is that low salaries and subsidies have scared away many experienced lawyers,” he said, suggesting that authorities, including the Ministry of Finance, should invest special funds to support a legal aid program and increase lawyers subsidies for legal assistance.

A lawyer only receives on average 1,500 yuan ($242) for a civil case and 1,200 yuan($193) for a criminal case, according to the Beijing Legal Aid Department.

The Ministry of Justice plans to invest at least 400 million yuan ($64.44 million) to support legal aid this year, according to Sun at the Justice Ministrys Legal Aid Department, as well as increasing the subsidies to lawyers for legal aid work.

Gu Yongzhong, a professor of criminal law at CUPL, said the quality of legal aid services is embodied in every aspect of the legal aid process.

“Quality control is a complicated question. We should consider all the process of legal assistance, including investigation, review and prosecution, not just the result,” Gu said.

He led a research team to inspect the implementation of legal aid at more than 30 legal aid institutions in 10 provinces after the promulgation of the new Criminal Procedure Law in 2014. The team found that lawyers were often absent from many links of the legal aid process, such as the investigative stage.

The June instruction gave a specific atten- tion to the problem, stating that once the police detain a criminal suspect, lawyers can immediately meet with the individual at the detention house to provide legal assistance.

Previously, when a criminal suspect was detained, lawyers had no means to make contact within 48 hours, and the police would not inform lawyers about the progress of the investigation, which seriously undermined a suspects legal rights, according to Vice Minister of Justice Zhao.

“After suspects are detained, lawyers will provide them with free legal aid services during the whole judicial procedure, including police interrogations, prosecution and court sentencing, to protect their rights,” Zhao said.

The instruction also highlighted the priority of accelerating legislation for the countrys legal aid services. A draft of the legislation will be transferred to the State Council for approval later this year, according to Sun.

When the legislation is complete, “appropriate authorities could clarify their tasks and work closely to improve the quality and professionalism of legal assistance and protect peoples legitimate rights”, said Zheng Huiyun, Director of the Beijing Legal Aid Department.

Zheng said the application procedures for legal aid services should be regulated, and more effort devoted to evaluating the quality of legal aid services and the mechanism for handling complaints from recipients of legal aid.

Sun said legal aid departments under local justice authorities would also establish an online updated database of legal aid recipients.