China: Through the Looking Glass

2015-06-05ByCorrieDosh

By+Corrie+Dosh

Bad though centuries of accumulated stereotypes about China may be, they have produced at least one benefit: great fashion. That seems to be the running theme in China: Through the Looking Glass, on exhibit now at New Yorks Metropolitan Museum of Art. Blending film, history and designer gowns, the Costume Institutes Spring 2015 exhibition is a veritable feast for the senses—exotic and dreamy. It is the “collective fantasy” of China that started with the first bolts of fabric traded on the Silk Road and the images of the Far East that have inspired artists and fashion designers for centuries.

In one room, embroidered silk French gowns are detailed with a delicate pattern of twisting branches and roses, while another shows off a Galliano mash-up of Chinese opera, Japanese kabuki and the Queen Mother of England. A gold lamé Guo Pei gown is set against sculptures of the Buddha.

An innovative show

The Yahoo-sponsored show is staged over three floors, from the basement-level Anna Wintour Costume Center to the Chinese galleries on the second floor. It is one of the museums largest exhibits ever, and a fitting tribute to the centennial celebration of the Mets Asian department. The fashion separates into generalized historical eras: China of the imperial dynasties, China the new republic, and the “cultural revolution”(1966-76). In the basement, a dark gallery lined with mirrors echoes with clips from Bernardo Bertoluccis 1987 film The Last Emperor, leading to a display of one of Emperor Puyis yellow robes on loan from the Palace Museum in Beijing. The historical display is juxtaposed with a yellow silk dress by John Galliano and a Tom Ford evening gown emblazoned with dragons.

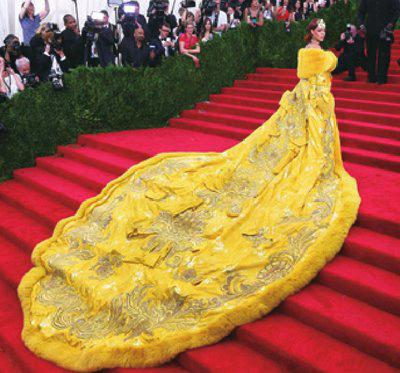

The royals of imperial America in the modern day are, of course, celebrities, and it was fitting that the annual Met Gala—the biggest night for avant-garde American fashion—celebrated the opening of the exhibit. The biggest names in film, music and media were pictured on the red carpet attired in their interpretations of the nights Chinese theme. Pop star Rihanna took top honors, snagging the cover of a special edition of Vogue, for her massive, canary-yellow Guo Pei gown that took three assistants to help carry—the creation was one of the few Chinese haute couture designers featured at the gala celebration.

“The focus and the attention paid to this dress will make it remembered by the world;[what] I want is to make them remember…. It is my responsibility to let the world know Chinas tradition and past, and to give the splendor of China a new expression. I hope that people do know China in this way,” Guo told The Cut, a New York City-based online fashion magazine.

The shows subtitle “Through the Looking Glass” translates into Chinese as “Moon in the Water,” a nod to Buddhism that suggests something is ineffable and has both positive and negative connotations. The Mets Astor Chinese Garden Court was transformed with an enormous, orange shimmering moon reflecting over the pond and a display of Peking Opera costumes of the like that inspired Gallianos spring 2003 Christian Dior Haute Couture Collection.

One room in the center of the exhibit is dedicated to a Chinese-American actress that had perhaps the greatest impact on shaping Western fantasies of China, Anna May Wong. Born in 1905, she was fated to play opposing stereotypes of the “enigmatic Oriental”—docile, obedient and submissive versus the predatory, calculating Dragon Lady. Constrained by one-dimensional caricatures, Anna May Wong moved to Europe and was embraced by the artistic avant-garde, inspiring designers like Marianne Brandt and Edward Steichen.

Film is the unifying element throughout the exhibition with clips of such classics as The World of Suzie Wong, Raise the Red Lantern and Red Detachment of Women. Internationally renowned filmmaker Wong Kar-wai is the exhibitions artistic director working with his longtime collaborator William Chang, who supervised styling.

Tomas Campbell, Director and CEO of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, called the exhibit“a monumental, immersive exploration of the influence of Chinese art and film and fashions greatest talents.”

The show brings together two of the Mets most “innovative” departments, the Costume Institute and Department of Asian Art, Campbell said.

“Its an inspiring mix of cultures, images and ideas that takes you on a truly cinematic journey,” he said.

Behind the scenes

A main sponsor of the exhibit was the Fosun Group, a Shanghai-based privately held conglomerate. Though declining to specify how much the company contributed, Patrick Zhong, Fosun head of global investments, told Beijing Review that sponsoring the exhibition is a source of pride for the company.

“To tell the Chinese story in the Metropolitan Museum, the worlds cultural mecca, has a very important significance,” Zhong said. “With the development of the Chinese economy, consumption and concepts have changed a lot. People are pursuing a high quality of life, and fashion is the best way to promote this. The Met Gala is fashionable and creative, adapting to our strategic concept, which is‘fashion and pleasure.”

The motif of “fashion and pleasure” is not limited to clothing, Zhong continued; Fosun wants to lead cultural trends. To that end it has recently taken a 33-percent stake in U.S.-based St. John Knits to partner with the labels push into China.

“Fosun invested in St. John Knits, making possible more opportunities for the companys development,” Zhong said. Before signing the deal, China contributed less than 1 percent of St. Johns annual sales, but Fosun estimates the Chinese market can contribute as much as 30 percent of annual sales for the line. The high-end suits sell for between 15,000 and 20,000 yuan ($2,400-3,200), speaking to the brands appeal to the growing ranks of Chinas nouveau riche.

In that way, the Mets latest venture into portraying the magical world of Chineseinfluenced fashion is as much practical as it is esoteric. The Chinese market cannot be ignored by any major design house in the modern era. The new consumer is globally minded, well traveled, incredibly rich and probably Chinese. An haute couture nod to the influence of Chinese artistic sensibilities is well timed.

The Met is one of the few institutions in the world that can host an exhibit like this, with its vast resources in historical Asian art and a worldrenowned fashion collection. The vast footprint of the galleries is somewhat overwhelming, as truly amazing details can be lost in the sheer volume of fashion on display.

“China: Through the Looking Glass demonstrates the potential of an encyclopedic museum to contextualize the impact of Chinese art on Western fashion over several centuries. The exhibitions point of departure is the fashions created in the West in response to changing notions of the East, beginning with the 18th century until the present,” said Maxwell K. Hearn, Douglas Dillon Chairman of the Mets Department of Asian Art. “In telling this story, the curatorial challenge has been to work back from these objects to discover the sources of these inspirations. What did these designers see, and what did they respond to?”

The underlying premise of the exhibition is simple: Its about the creative process, Hearn said. Artists making connections are not inhibited by space, time or culture. They can use influences without fully understanding them—or, rather, they understand these things in their own way and use them to solve their own creative challenges.

The idea to feature Chinese-influenced fashion began “rather modestly” two years ago, said Andrew Bolton, curator of the Costume Institute at the Met. Instead of the original plan of staging the show in the costume galleries and three of the Asian art rooms, the exhibition blossomed into a show three times the size of the typical Costume Institute affair, spanning over 30,000 square feet (2,787 square meters).

“Its a truly interdepartmental exhibition,”Bolton said, “featuring pieces from over 60 lenders, including museums and design houses in Asia and Europe.”

Some of the works are being unveiled for public view after decades in storage, such as a portrait of the “fragrant concubine” on loan from the Palace Museum in Beijing. The careful juxtaposition of Western pieces and Chinese art aims to facilitate new interpretations and provide a new context for the viewer.

For example, a gallery playing clips from the 2000 film In the Mood for Love directed by the exhibitions artistic director Wong Kar-wai features an array of stunning qipao gowns along with romantic lighting that allows the viewer to conjure in their minds the steamy, mythical China portrayed by the film.

“This show has been a truly remarkable journey,” said Wong Kar-wai. “One of the most fascinating parts of this journey for myself was the opportunity to revisit the Western perspective of China. Fashion designers took those distortions and created a new Western aesthetic. In this exhibition, we didnt shy away from these distortions because they are historical fact. Instead, we looked for areas of commonality. It is a celebration of fashion, cinema and creativity.”