结核分枝杆菌潜伏感染预防性治疗的进展

2015-05-22艾静文阮巧玲张文宏

艾静文 阮巧玲 张文宏

·综述·

结核分枝杆菌潜伏感染预防性治疗的进展

艾静文 阮巧玲 张文宏

结核分枝杆菌潜伏感染(latent tuberculosis infection,LTBI)的预防性治疗在结核病防治中扮演着重要角色。使用肿瘤坏死因子拮抗剂(tumor necrosis factor antagonist, TNF antagonist)的患者、人类获得性免疫缺陷病毒(human immunodeficiency virus, HIV)感染者、活动性结核病的密切接触者等高危人群中的LTBI者接受积极的预防性治疗可以降低结核病发病率。国际上目前推荐的LTBI常规治疗方案为9个月的异烟肼治疗方案(9INH)。其他治疗方案还包括6个月的异烟肼治疗方案(6INH),4个月利福平治疗方案(4RFP),3个月利福平+异烟肼治疗方案[3(RFP+INH)],以及3个月的利福喷丁+异烟肼治疗方案[3(Rft+INH)]等。在中国,LTBI者基数较大,尽早开展我国LTBI者预防性治疗对于控制结核病疫情有着积极意义。但中国耐药人数已是世界第一,对于预防性抗结核治疗的人群限定需更慎重,避免进一步增加耐药率。

潜伏性结核/药物疗法; 潜伏性结核/预防和控制; 临床方案

结核分枝杆菌(Mycobacterium tuberculosis,Mtb)感染是一个慢性免疫病理状态,感染Mtb后可出现3种结局:Mtb被清除;Mtb呈现明显的复制并出现临床症状,临床称为活动性结核病;Mtb被控制但未被清除,呈休眠状态,即结核分枝杆菌潜伏感染(latent tuberculosis infection,LTBI),此时机体不表现出临床症状但又不能将其彻底清除。但当机体出现免疫力低下时,Mtb能被重新激活并复制,发展成为活动性结核病并成为新的传染源。据WHO估计,全世界约有20亿例LTBI者[1-2],其中5%~10%会在其一生中发展为活动性结核病[3]。因此,对于LTBI者早期进行预防性治疗,能够大大降低其发展成为活动性结核病的概率,有效控制结核病传播。在结核病高发地区,治疗活动性结核病患者仍是控制结核病传播的重点;而在结核病低流行地区,预防性治疗LTBI者更为重要。目前,LTBI者的预防性治疗研究主要集中于LTBI高危人群的筛查和预防性治疗方案的选择2个方面。

中国是结核病高发国家,年发病例数达100万例,15岁及以上人群中肺结核患者约700万例,而潜伏性结核感染率高达44.5%[4],提示LTBI者在中国人群中所占比重较大。尽早全面开展我国LTBI者的预防性治疗对于控制我国结核病传播有着积极意义。

一、LTBI高危人群的筛查

迄今为止,LTBI的诊断缺乏金标准。由于LTBI者体内Mtb菌量少,因此诊断主要依靠检测宿主对Mtb感染的特异性免疫反应,而不是检测细菌本身。现有的筛查试验有结核菌素皮肤试验(TST)和γ-干扰素释放试验(interferon-gamma release assays, IGRAs),IGRAs包括QuantiFERON-TB Gold和结核感染T细胞斑点试验(T-SPOT.TB)两种主要的商业化试剂盒。TST曾是常规诊断Mtb感染的手段,但其敏感度仅为70%[5],且无法区分潜伏性与非潜伏性的感染。IGRAs具有更高的敏感度和特异度,敏感度可超过90%。但基于成本-效益角度考虑,目前TST试验仍是各项临床研究的主要实验室诊断手段。但对于接种过卡介苗的大部分中国人来说,TST常呈假阳性结果,所以IGRAs试验应在中国进一步推广。

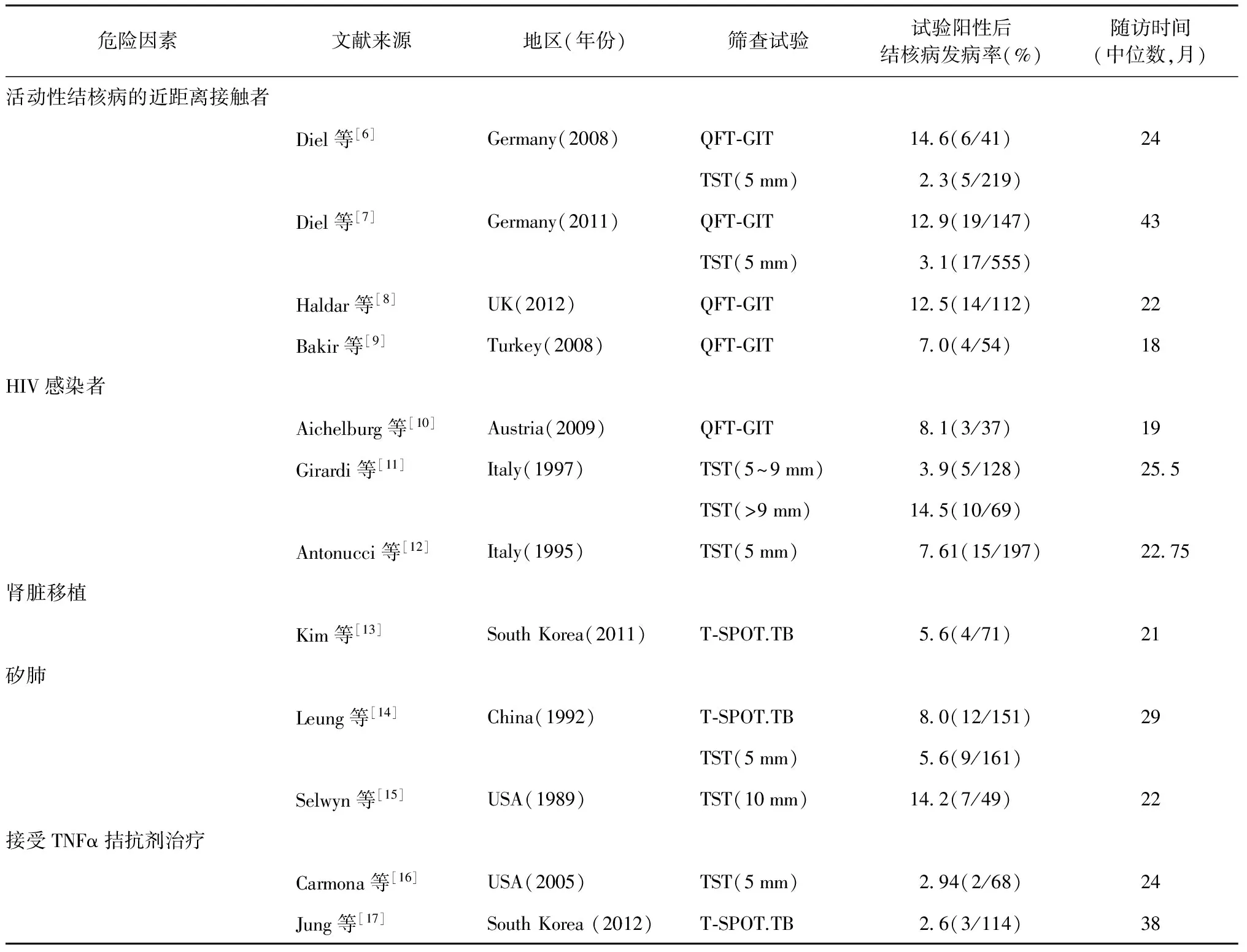

在普通人群中仅有5%~10% IGRAs试验阳性的患者会在之后发展为活动性结核病[3]。所以进一步从TST或IGRAs试验阳性人群中筛选出更易发展为活动性结核病的高危人群是潜伏性结核预防性治疗的重点。目前已知的导致潜伏性结核发展至活动性结核病的高危因素包括活动性结核病密切接触者、器官移植、透析、人类获得性免疫缺陷病毒(human immunodeficiency virus, HIV)感染、免疫抑制药物使用等。LTBI者的结核病发病率与部分高危因素的相关性如表1所示。

1. 活动性结核病密切接触者:研究表明,近期感染的LTBI者(PPD试验结果在过去2个月内由阴转阳)相对于其他LTBI者发生活动性肺结核概率会增加15倍[18],而活动性结核病的密切接触者是LTBI近期感染的主要群体。因此,对于活动性肺结核的密切接触者,一旦筛查试验阳性,考虑他们是近期感染的可能性就较高。这其中,家庭或学校或监狱等环境的密切接触者应接受LTBI的预防性治疗。而结核病专科和呼吸科医生等密切接触者,由于接受LTBI的预防性治疗后,他们还要继续接触结核病患者,有再次被感染的可能,因此预防性治疗对于这类人群的作用尚不明确。

2. 免疫缺陷患者:因为各种病理因素所致的免疫缺陷患者是活动性结核病的高危人群,包括先天性免疫缺陷患者、HIV感染者、器官移植的患者等。其中,HIV感染致LTBI发展为活动性结核病的风险最高。各类研究报道了HIV感染者的活动性肺结核发生风险可增加约50~170倍不等[18],而伴有HIV感染的LTBI者其终生活动性肺结核发病风险高达30%,远高于HIV阴性者。WHO在2011年发表的针对HIV流行地区的指南中强烈推荐对于HIV感染者,不论LTBI筛查试验结果阳性与否,均应进行异烟肼(INH)的预防性治疗[19]。

3. 接受免疫抑制药物治疗的患者:近年来,糖皮质激素、改善病情抗风湿药(disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, DMARDs)等免疫抑制药物均被发现可增加LTBI者的结核病发病率。其中,肿瘤坏死因子(tumor necrosis factor, TNF)拮抗剂的危险度最高。TNF是机体对Mtb产生免疫应答从而将其清除中的关键因子,也是参与机体炎症反应的重要因子[20]。近年来,TNF拮抗剂已成为治疗慢性炎症性疾病的新手段,接受TNF拮抗剂治疗的患者其结核病发病率增加了1.6~25.1倍[21]。TNF拮抗剂包括TNF单株抗体和TNF可溶性受体,目前国内已上市的TNF拮抗剂有英夫利昔单抗、依那西普和阿达木单抗。上述3类药物引起的活动性结核病的发病率(IR)分别为383/100 000、114/100 000、176/100 000[21]。Solovic等[21]建议LTBI者若需要使用TNF拮抗剂,应提前1~2个月进行LTBI的预防性治疗。德国和瑞士在指南中建议对IGRAs试验筛查阳性的患者进行结核病预防性治疗[22-23]。在一项针对将要进行TNF拮抗剂治疗的西班牙LTBI者的回顾性研究中,没有完成9个月异烟肼疗程(9INH)的预防性治疗组发生活动性结核病的概率比完成组高出7倍[24]。美国的一项类似研究表明:同时接受戈利木单抗和异烟肼预防性治疗LTBI的317例患者中,没有活动性结核病发生的患者[25]。国际上目前对于采取何种预防性治疗方案仍无定论,而我国结核病预防与管理专家组建议,对存在LTBI的患者,在使用英夫利昔单抗前,先行预防性抗结核治疗至少4周,但需注意药物间的相互作用[26]。

表1 TST或IGRAs试验阳性但未接受预防性治疗的受试者的活动性结核病发病率危险因素分析

注 QFT-GIT:第三代γ-干扰素释放试验;TNF:肿瘤坏死因子;TST:结核菌素试验;表中括号内数值分子为结核病发病例数,分母为试验阳性例数

其他生物制剂,如IL-6单株抗体、IL-12单株抗体、IL-1β单株抗体、抗CD20单株抗体被普遍认为可以增加LTBI者结核病发病的风险,但仍缺乏具体数据。对于使用糖皮质激素的患者,其危险度增加2.8~7.7倍不等[27]。对于使用DMARDs进行治疗的风湿病患者,如果存在其他高危因素,那么其结核病发病率也将增加,但目前是否需要预防性治疗仍缺乏依据。

4. 其他相关疾病患者或其他高危人群:矽肺、糖尿病患者、慢性肾脏病5期需要透析的患者、吸烟者、卫生保健工作者结核病发病的风险均有提高,其中矽肺的危险度最高。目前,国际上尚未达成共识。一些指南推荐对于这部分人群常规进行LTBI的筛查试验,并对筛查试验阳性的患者进行预防性治疗[28-29]。

二、LTBI的预防性治疗方案

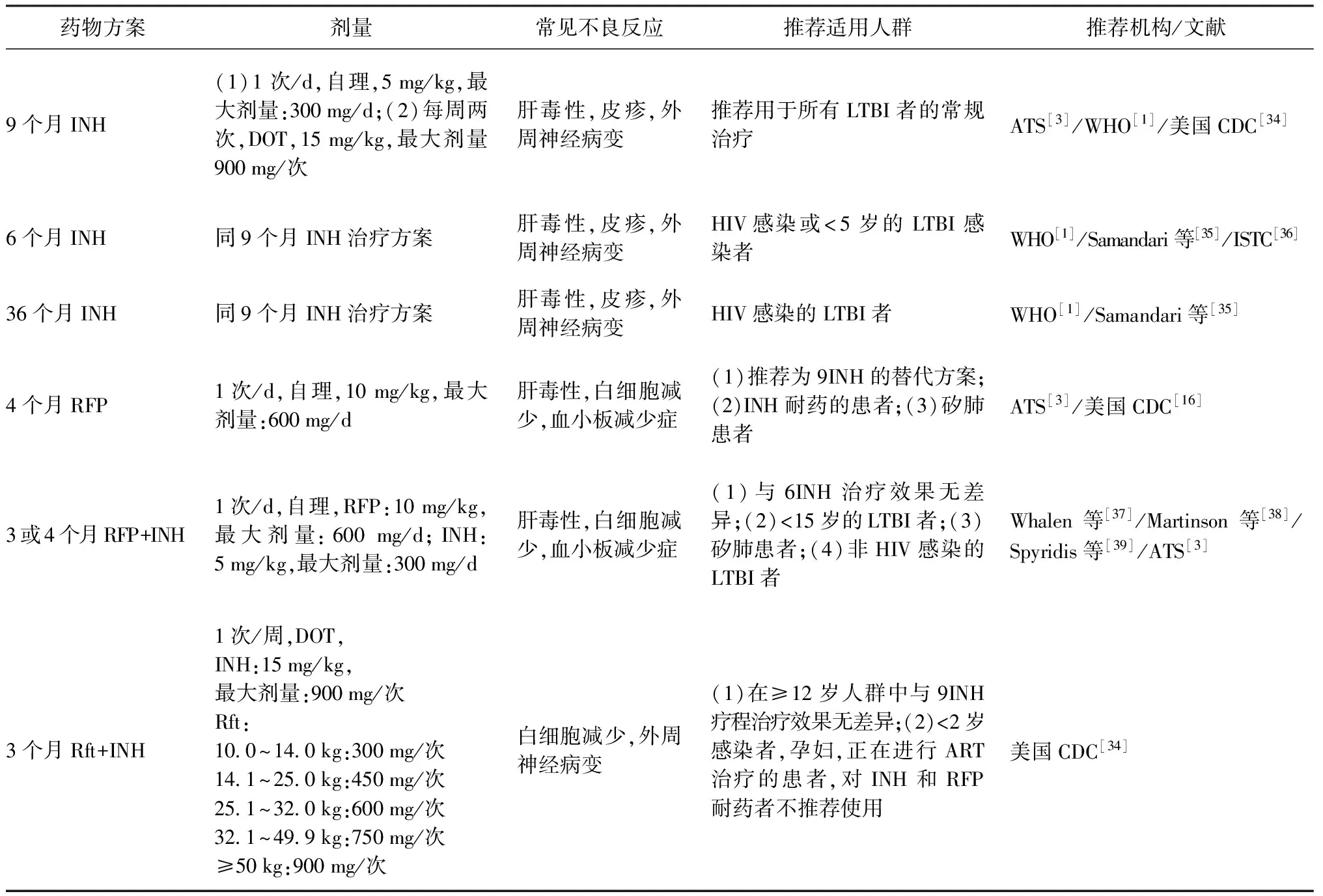

关于LTBI的预防性治疗方案在近几十年来有了很大进展[30-33]。表2列出了WHO、美国胸科协会(ATS)、美国疾病预防控制中心(美国CDC)以及《国际结核病关怀标准(ISTC)》联合推荐的几种预防性治疗方案。

1. 异烟肼单药方案:在20世纪50年代至70年代之间,针对异烟肼治疗LTBI展开的多项临床研究均提示每日或间歇服用异烟肼可以减少活动性结核病的发病率[30-31]。对于非HIV感染者,临床研究发现12INH或6INH能够提供更好的保护作用[32]。Comstock[33]将多个临床试验数据建模分析后,认为对于LTBI者,9INH相对于12INH或6INH会有更好的效果。2000年美国ATS发表的指南中首次将9INH列为了LTBI预防性治疗的首选方案[3]。一项针对肾脏移植患者或肾脏透析患者进行的12INH预防性治疗的研究结果提示,结核病发病率相对于安慰剂组差异并没有统计学意义。这也是国际上目前惟一一个针对器官移植患者进行预防性治疗的临床研究。在针对HIV感染者的研究中,几项临床研究均显示6~12个月的异烟肼治疗可以减少活动性结核病的发病率,预防的效果在各项研究中不尽相同(32%~64%)[40-41]。2个基于多项临床随机试验的Meta分析提示对于TST试验阳性的HIV感染者,异烟肼可以显著降低活动性结核病的风险性,但在高危地区,活动性结核病发病率相应增高[42]。一项2011年发表的针对TST筛查试验阳性的HIV感染者的大型随机临床试验表明,36INH疗程相对于6INH疗程可以更有效的减少活动性结核病的发病率[35]。目前国际上广泛认可6个月、9个月和持续性(36个月)异烟肼疗程作为LTBI的预防性治疗的方案。然而,在2014年最新发表的一项针对南非矿工的结核病预防性治疗的研究表明,9INH组与安慰剂组相比,长期的结核病发病率差异并无统计学意义[43]。这一结果也给异烟肼的预防性治疗带来了挑战。一个可能的解释是该研究纳入的受试者为所有的矿工人群而非其中的LTBI者,而纳入大量的非潜伏性结核感染者会降低结核病发病率从而影响研究结果。

表2 临床推荐LTBI预防性治疗疗法

注 ART:抗逆转录病毒治疗;ATS:美国胸科协会:CDC:疾病预防控制中心;DOT:直接督导治疗;INH:异烟肼;RFP:利福平;Rft:利福喷丁

随着异烟肼在LTBI的预防性治疗中的广泛运用,其不良反应也逐渐被人们所关注。1970—1971年间,美国公共卫生中心监测了14 000例服用异烟肼的LTBI者,结果显示肝炎的发生率为1%~2.3%[3]。Menzies等[44]报道了9INH可以导致严重肝毒性(3.8%);其他不良反应,如外周神经病变等,也被提及。

2. 利福平单药方案或利福平联合异烟肼方案:矽肺是肺结核的高危因素。在1992年发表的一项针对香港矽肺患者的临床随机对照研究中,研究人员比较了3个月利福平+异烟肼[3(RFP+INH)]、3个月利福平(3RFP)、6个月异烟肼(6INH)以及安慰剂这四组方案对于活动性肺结核发生率的影响。研究发现安慰剂组5年累积发病率高于其余3组[安慰剂组:27%;3(RFP+INH)组:16%;6INH组:14%;3RFP组:10%][14]。这一研究首次提示利福平单药方案和利福平与异烟肼联合用药方案可用于结核病的预防性治疗。4RFP还被证实可以减少肝脏毒性,并具有更高的成本-效益优势[45]。而3(RFP+INH)和4(RFP+INH)方案被证实对于儿童是安全的[39]。2007年一项研究认为6INH、3(INH+RFP)、3(INH+RFP+PZA) 3个方案都能减少HIV感染者活动性结核病的发病率,但多药联合方案更易产生不良反应[37]。而在2011年的一项针对HIV感染者的研究中,3(RFP+INH)方案的预防性治疗效果不优于6INH方案[38]。ATS在指南中推荐4个月利福平方案(4RFP)作为那些无法进行9INH的患者的替代方案[3],但其依据仅源于针对3RFP方案的研究结果[14]。目前,针对4RFP的方案的2个临床实验已经在进行中,临床试验官网的检验号(clinicaltrials.gov identifiers)为:NCT00931736、NCT01398618。

3. 利福喷丁联合异烟肼方案:长达3个月,每周1次的利福喷丁+异烟肼方案[3(Rft+INH)],目前被认为最有望取代9INH方案。一项包含7731例非HIV受试者的研究发现,3(Rft+INH)相对于9INH方案不具有劣势[46],此外,前组具有更高的完成率和更低的肝脏毒性作用。这项临床研究采用的是直接监督下的治疗(directly observed treatment,DOT),DOT 对于疗程效果的影响仍有待进一步观察。目前,一项针对DOT对于疗程的影响的研究正在进行(clinicaltrials.gov identifier:NCT01582711)。而在一项针对1148例HIV感染者的研究中,比较了3(Rft+INH)、3(RFP+INH)、6INH、持续性INH 4个方案的治疗效果,结果显示各组的效果差异无统计学意义[38]。

4. 利福平联合吡嗪酰胺方案:另一项针对HIV感染者的LTBI感染的治疗方案为2个月的利福平+吡嗪酰胺[2(RFP+PZA)]疗程,这一方案已在临床研究中被证明有效[47-48],但是2(RFP+PZA)方案很快被发现可能引起严重的肝脏毒性[49-50],严重者可导致死亡。ATS和(或)CDC的指南目前不推荐在LTBI者中使用此方案,若患者对于异烟肼有严重不良反应转而接受2 (RFP+PZA)方案治疗时,必须在第2、4、6周时接受肝功能的检测[42]。

虽然3(Rft+INH)和4RFP方案被寄予厚望,但目前没有证据证明任何一种治疗方案比6INH、9INH方案具有更好的治疗效果,所以,也有研究将重点放在几种方案间的成本-效益的比较。Holland等[51]报道了4RFP相比于9INH方案更具有成本-效益优势,而3(Rft+INH)方案在高危人群中更具有成本-效益优势。

三、国内LTBI预防性治疗的现状

我国建议对将要使用英夫利昔单抗的LTBI感染者,行预防性治疗至少4周。而相继也有临床研究证实了9INH方案对于PPD阳性的HIV感染者具有保护作用[52]。在一项高校结核病的研究中,研究者对于PPD硬结平均直径≥15 mm的新入学学生给予每周2次口服利福喷丁和异烟肼,共3个月的预防性治疗。结果显示预防性治疗对发生结核病的保护率为74.8%[53]。在WHO 2011年发表的《世界耐抗结核病药物更新报告》中,中国抗结核病药物耐药率高达38.8%[54],而中国人口基数巨大,中国耐药人数实际已是世界第一。因此,对于预防性抗结核治疗的人群限定需要更为慎重,避免因为扩大预防性治疗而进一步增加耐药率。目前,我国推荐对HIV感染者、长期使用免疫抑制剂患者,以及准备接受TNF-α拮抗剂治疗的患者进行LTBI的预防性治疗,而对于矽肺患者及活动性结核病密切接触者,是否需要预防性治疗仍存在争议。同时,我国也开展了针对学校和监狱中LTBI的筛查进行预防性治疗的研究,正是在人群密集区,针对结核病疫情应该采取进一步控制措施[55-56]。在预防性抗结核治疗的方案选择上,9INH方案已被证实可以应用于所有人群并能减少LTBI发展至活动性结核病的概率。Khan等[36]2002年在《The New England Journal of Medicine》上发表了不同药物对美国移民的LTBI预防性治疗的成本-效益分析,结果也表明对于中国移民,异烟肼方案相比于利福平单药和利福平联合吡嗪酰胺方案更具有成本-效益性。因此9INH的治疗方案可在国内推广。但值得注意的是,Cain等[57]在2008年发表的针对在美国外出生的美国居民的研究表明,出生于中国、居住在美国的结核病患者对于异烟肼的耐药率可达到16%。而中国异烟肼的耐药率也很高,因此用异烟肼预防存在着进一步增加耐药率的危险性。

四、总结

LTBI的预防性治疗对于控制全世界结核病发病率有着积极的意义,筛查出的LTBI的高危人群如果符合预防性治疗的条件,应积极予以治疗。国际上目前推荐的LTBI的首选治疗方案为9INH方案;其他被广泛认可的治疗方案有6INH、4RFP、3(Rft+INH)。一些临床研究报道了4RFP可作为9INH的替代治疗方案,而3(Rft+INH)方案则有最好的完成率和不劣于9INH方案的疗效。但短程方案的有效保护期是否能够达到和长程方案同样的效果仍不得而知。我国是结核病高流行地区,同时耐多药结核病患者的绝对人数位居世界第一位[1],因此,限定接受预防性治疗的人群非常关键。未来应进一步探索适合中国人的抗结核病药物,缩短治疗疗程,降低耐药率,提高治疗依从性,并最终降低结核病发病率。

[1] Zumla A, George A, Sharma V, et al. Who’s 2013 global report on tuberculosis: successes, threats, and opportunities. Lancet, 2013, 382(9907): 1765-1767.

[2] Bennett DE, Courval JM, Onorato I, et al. Prevalence of tuberculosis infection in the United States population: the national health and nutrition examination survey, 1999—2000. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2008, 177(3): 348-355.

[3] American Thoracic Society. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2000, 49 (RR-6): 1-51.

[4] 全国结核病流行病学抽样调查技术指导组, 全国结核病流行病学抽样调查办公室. 2000年全国结核病流行病学抽样调查报告. 中国防痨杂志, 2002, 24(2): 65-108.

[5] Parekh MJ, Schluger NW. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Ther Adv Respir Dis, 2013, 7(6): 351-356.

[6] Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Meywald-Walter K, et al. Predictive value of a whole blood IFN-gamma assay for the development of active tuberculosis disease after recent infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2008, 177(10): 1164-1170.

[7] Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Niemann S, et al. Negative and positive predictive value of a whole-blood interferon-γ release assay for developing active tuberculosis: an update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2011, 183(1): 88-95.

[8] Haldar P, Thuraisingam H, Patel H, et al. Single-step QuantiFERON screening of adult contacts: a prospective cohort study of tuberculosis risk. Thorax, 2013, 68(3): 240-246.

[9] Bakir M, Millington KA, Soysal A, et al. Prognostic value of a T-cell-based, interferon-gamma biomarker in children with tuberculosis contact. Ann Intern Med, 2008, 149(11): 777-787.

[10] Aichelburg MC, Rieger A, Breitenecker F, et al. Detection and prediction of active tuberculosis disease by a whole-blood interferon-gamma release assay in HIV-1-infected individuals. Clin Infect Dis, 2009, 48(7): 954-962.

[11] Girardi E, Antonucci G, Ippolito G, et al. Association of tuberculosis risk with the degree of tuberculin reaction in HIV-infected patients. The Gruppo Italiano di Studio Tubercolosi e AIDS. Arch Intern Med, 1997, 157(7): 797-800.

[12] Antonucci G, Girardi E, Raviglione MC, et al. Risk factors for tuberculosis in HIV-infected persons. A prospective cohort study. The Gruppo Italiano di Studio Tubercolosi e AIDS (GISTA). JAMA, 1995, 274(2): 143-148.

[13] Kim SH, Lee SO, Park JB, et al. A prospective longitudinal study evaluating the usefulness of a T-cell-based assay for latent tuberculosis infection in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant, 2011, 11(9): 1927-1935.

[14] Hong Kong Chest Service/Tuberculosis Research Centre, Madras/British Medical Research Council. A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of three antituberculosis chemoprophylaxis regimens in patients with silicosis in Hong Kong. Am Rev Respir Dis, 1992, 145(1): 36-41.

[15] Selwyn PA, Hartel D, Lewis VA, et al. A prospective study of the risk of tuberculosis among intravenous drug users with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med, 1989, 320(9): 545-550.

[16] Carmona L, Gómez-Reino JJ, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Effectiveness of recommendations to prevent reactivation of latent tuberculosis infection in patients treated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Arthritis Rheum, 2005, 52(6): 1766-1772.

[17] Jung YJ, Lyu J, Yoo B, et al. Combined use of a TST and the T-SPOT.TB assay for latent tuberculosis infection diagnosis before anti-TNF-α treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2012, 16(10): 1300-1306.

[18] Landry J, Menzies D. Preventive chemotherapy. Where has it got us? Where to go next? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2008, 12(12): 1352-1364.

[19] World Health Organization. Guidelines for intensified tuberculosis case-finding and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings. Geneva: WHO, 2011.

[20] Ehlers S. Tumor necrosis factor and its blockade in granulomatous infections: differential modes of action of infliximab and etanercept? Clin Infect Dis, 2005, 41 Suppl 3: S199-203.

[21] Solovic I, Sester M, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. The risk of tuberculosis related to tumour necrosis factor antagonist therapies: a TBNET consensus statement. Eur Respir J, 2010, 36(5): 1185-1206.

[22] Diel R, Hauer B, Loddenkemper R, et al. Recommendations for tuberculosis screening before initiation of TNF-alpha-inhi-bitor treatment in rheumatic diseases. Z Rheumatol, 2009, 68(5): 411-416.

[23] Beglinger C, Dudler J, Mottet C, et al. Screening for tuberculosis infection before the initiation of an anti-TNF-alpha therapy. Swiss Med Wkly, 2007, 137(43/44): 620-622.

[24] Gómez-Reino JJ, Carmona L, Angel Descalzo M, et al. Risk of tuberculosis in patients treated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists due to incomplete prevention of reactivation of latent infection. Arthritis Rheum, 2007, 57(5): 756-761.

[25] Hsia EC, Cush JJ, Matteson EL, et al. Comprehensive tuberculosis screening program in patients with inflammatory arthritides treated with golimumab, a human anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody, in phase Ⅲ clinical trials. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2013, 65(2): 309-313.

[26] 英夫利昔单抗治疗前结核预防与管理专家建议组. 英夫利昔单抗治疗前结核预防与管理专家建议. 中华内科杂志, 2009, 48(11): 980-982.

[27] Jick SS, Lieberman ES, Rahman MU, et al. Glucocorticoid use, other associated factors, and the risk of tuberculosis. Arthritis Rheum, 2006, 55(1): 19-26.

[28] British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee and Joint Tuberculosis Committee, Milburn H, Ashman N, et al. Guidelines for the prevention and management of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and disease in adult patients with chronic kidney disease. Thorax, 2010, 65(6): 557-570.

[29] Harries AD, Lin Y, Satyanarayana S, et al. The looming epidemic of diabetes-associated tuberculosis: learning lessons from HIV-associated tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2011, 15(11): 1436-1445.

[30] Egsmose T, Ang’awa JO, Poti SJ. The use of isoniazid among household contacts of open cases of pulmonary tuberculosis. Bull World Health Organ, 1965, 33(3): 419-433.

[31] Akolo C, Adetifa I, Shepperd S, et al. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in HIV infected persons. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2010,(1): CD000171.

[32] International Union Against Tuberculosis Committee on Prophylaxis. Efficacy of various durations of isoniazid preventive therapy for tuberculosis: five years of follow-up in the IUAT trial. Bull World Health Organ, 1982, 60(4): 555-564.

[33] Comstock GW. How much isoniazid is needed for prevention of tuberculosis among immunocompetent adults? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 1999, 3(10): 847-850.

[34] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations for use of an isoniazid-rifapentine regimen with direct observation to treat latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2011, 60(48): 1650-1653.

[35] Samandari T, Agizew TB, Nyirenda S, et al. 6-month versus 36-month isoniazid preventive treatment for tuberculosis in adults with HIV infection in Botswana: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet, 2011, 377(9777): 1588-1598.

[36] Khan K, Muennig P, Behta M, et al. Global drug-resistance patterns and the management of latent tuberculosis infection in immigrants to the United States. N Engl J Med, 2002, 347(23): 1850-1859.

[37] Whalen CC, Johnson JL, Okwera A, et al. A trial of three regimens to prevent tuberculosis in Ugandan adults infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Uganda-Case Wes-tern Reserve University Research Collaboration. N Engl J Med, 1997, 337(12): 801-808.

[38] Martinson NA, Barnes GL, Moulton LH, et al. New regimens to prevent tuberculosis in adults with HIV infection. N Engl J Med, 2011, 365(1): 11-20.

[39] Spyridis NP, Spyridis PG, Gelesme A, et al. The effectiveness of a 9-month regimen of isoniazid alone versus 3- and 4-month regimens of isoniazid plus rifampin for treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in children: results of an 11-year randomized study. Clin Infect Dis, 2007, 45(6): 715-722.

[40] Pape JW, Jean SS, Ho JL, et al. Effect of isoniazid prophylaxis on incidence of active tuberculosis and progression of HIV infection. Lancet, 1993, 342(8866): 268-272.

[41] Grant AD, Charalambous S, Fielding KL, et al. Effect of routine isoniazid preventive therapy on tuberculosis incidence among HIV-infected men in South Africa: a novel randomized incremental recruitment study. JAMA, 2005, 293(22): 2719-2725.

[42] Bucher HC, Griffith LE, Guyatt GH, et al. Isoniazid prophylaxis for tuberculosis in HIV infection: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. AIDS, 1999, 13(4): 501-507.

[43] Churchyard GJ, Fielding KL, Grant AD. A trial of mass isoniazid preventive therapy for tuberculosis control. N Engl J Med, 2014, 370(17): 1662-1663.

[44] Menzies D, Dion MJ, Rabinovitch B, et al. Treatment completion and costs of a randomized trial of rifampin for 4 months versus isoniazid for 9 months. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2004, 170(4): 445-449.

[45] Menzies D, Long R, Trajman A, et al. Adverse events with 4 months of rifampin therapy or 9 months of isoniazid therapy for latent tuberculosis infection: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med, 2008, 149(10): 689-697.

[46] Sterling TR, Villarino ME, Borisov AS, et al. Three months of rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med, 2011, 365(23): 2155-2166.

[47] Gordin F, Chaisson RE, Matts JP, et al. Rifampin and pyrazinamide vs isoniazid for prevention of tuberculosis in HIV-infected persons: an international randomized trial. Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS, the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group, the Pan American Health Organization, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Study Group. JAMA, 2000, 283(11): 1445-1450.

[48] Halsey NA, Coberly JS, Desormeaux J, et al. Randomised trial of isoniazid versus rifampicin and pyrazinamide for prevention of tuberculosis in HIV-1 infection. Lancet, 1998, 351(9105): 786-792.

[49] From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fatal and severe hepatitis associated with rifampin and pyrazinamide for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection—New York and Georgia, 2000. JAMA, 2001, 285(20): 2572-2573.

[50] From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: Fatal and severe liver injuries associated with rifampin and pyrazinamide for latent tuberculosis infection, and revisions in American Thoracic Society/CDC recommendations—United States, 2001. JAMA, 2001, 286(12): 1445-1446.

[51] Holland DP, Sanders GD, Hamilton CD, et al. Costs and cost-effectiveness of four treatment regimens for latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2009, 179(11): 1055-1060.

[52] 殷继国, 何卫华, 练祖银, 等. HIV/AIDS患者结核感染预防性治疗效果评价研究. 中国防痨杂志, 2010, 32(12): 791-794.

[53] 刘玉清, 屠德华, 安燕生, 等. 大学生结核病控制的研究:(二)结核感染者的预防性治疗. 中国防痨杂志, 2005, 27(3): 139-142.

[54] Zignol M, van Gemert W, Falzon D, et al. Surveillance of anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in the world: an updated analysis, 2007—2010. Bull World Health Organ, 2012, 90(2): 111-119D.

[55] 王海英, 蒋彩花, 王俊玲, 等. 山东省某监狱劳教人员结核病筛查结果分析.中国防痨杂志, 2009, 31(6):327-330.

[56] 路希维. 学校结核病暴发控制策略研究进展. 中国防痨杂志, 2013, 35(9):752-756.

[57] Cain KP, Benoit SR, Winston CA, et al. Tuberculosis among foreign-born persons in the United States. JAMA, 2008, 300(4): 405-412.

(本文编辑:郭萌)

Advances in the preventive treatment of latent tuberculosis infection

AI Jing-wen,RUAN Qiao-ling,ZHANG Wen-hong.

Department of Infectious Diseases, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200040, China

Corresponding author:ZHANG Wen-hong,Email:zhangwenhong@fudan.edu.cn

The prophylactic treatment of latent tuberculosis infection plays an important role in the prevention and treatment of tuberculosis. In recent years, studies have reported that HIV-infected patients, close contacts of active tuberculosis, and patients who use tumor necrosis factor antagonists should take the prophylactic treatment for latent tuberculosis infection. The currently preferred treatment is 9 months of isoniazid therapy (9INH), other regimens includes 6 months of isoniazid therapy (6INH), 4 months of rifampicin therapy (4RFP), 3 months of rifampin + isoniazid program (3(RFP+INH)), 3 months rifapentine + isoniazid program (3(Rft+INH)). In China, due to the large number of latent tuberculosis infection, it is of great importance to launch the preventive treatment. However, the number of drug resistant patients ranked the first in the world, careful evaluation should be conducted in order to avoid the further increase in drug resistance.

Latent tuberculosis/drug therapy; Latent tuberculosis/prevention & control; Clinical protocols

10.3969/j.issn.1000-6621.2015.01.015

200040 上海,复旦大学附属华山医院感染科

张文宏,Email:zhangwenhong@fudan.edu.cn

2014-08-23)