Paper Trail:Hunting Financial Fugitives

2015-03-16byWangShuo

by+Wang+Shuo

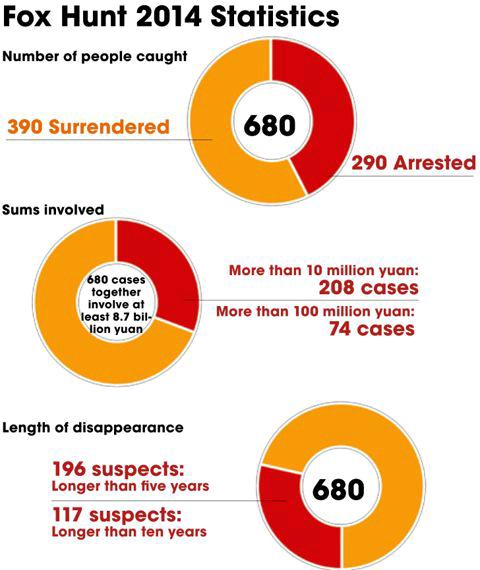

As China continues its high- pressure anti-corruption campaign, efforts have been intensified to catch economic fugitives abroad through international collaboration and confiscate their ill-gotten gains. A special campaign with this aim was launched on July 22, 2014 by Chinas public security authority, targeting the capture of suspected economic criminals residing overseas.

As explained by Zhuang Deshui, deputy director of the Research Center for the Construction of a Clean Government under Peking University, high-ranking officials with incredible economic means tend to flee to developed Western countries such as the United States, Canada, and Australia, whereas lower-ranking officials with comparatively less money tend to flee on a whim to more convenient destinations such as Thailand, Myanmar, and Russia. In addition, those who encounter difficulties getting a passport and visa are often left with smuggling themselves into underdeveloped countries in Africa and Latin America.

Hunting 24/7

Liu Dong, head of the Fox Hunt 2014 Office and deputy director of the Bureau of Economic Investigation under the Ministry of Public Security, likens his crew to“hunters.” This hunting mission is full of twists and turns especially because many fugitives become quite adept at hiding.

“Its hard to track our suspects because of an inadequate flow of information when tracing them overseas,” Liu illustrates.“We ultimately captured a suspect with the help of local police after analyzing a wide variety of information and clues through street lamps, manhole covers, and even the crosswalk in an unimpressive picture of a white cat.”

“It was like riding a roller coaster,”gasps Meng Jin, one “hunter,” upon recalling his mission in Uganda in July 2014.“We were targeting Li, suspected of illegal assimilation of public savings when he ran a company in Jiangsu Province. We found him in a casino. Even though my partner and I were sitting on either side of him, we could not take him into custody because the local police didnt work on weekends. We eventually got him handcuffed on Monday when he returned to the casino.”

Such missions are much more difficult than domestic cases even with full support from local law enforcement. Hunters must address issues such as cultural differences and protocol for handling cases as well as difficulties caused by language, scheduling and complex procedures.

Late one night weeks ago, Xia Xiaomo, one hunter, was still busy in his office when he was notified of an urgent assignment to escort an apprehended suspect from Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, to China in 24 hours. According to regulations in many countries, suspects caught by local police for foreign crimes must be released if they are not transferred to Chinese custody within 24 or 48 hours. Xia arrived at the airport at 3 a.m. after getting necessary documents translated and booking a flight. He handled every procedure lightning fast and flew back to China at 5:00 a.m. the next day. “Working like that is nothing new,” Xia sighed.

Intensified International Cooperation

Extradition is fundamental judicial cooperation in the pursuit of suspects evading arrest by traveling overseas, but it requires a specific condition: The alleged act must be considered criminal in both countries.“At present, most countries that have signed a bilateral extradition treaty with China are found in South Asia and Africa,”explains Deputy Director Zhuang. “China hasnt signed such an agreement with most European countries or the United States, making them more appealing for fugitive corrupt officials. Efforts should be made to hasten negotiations with Western countries before its too late.”

Handcuffing criminals is not the sole goal of their efforts. Many of their cases involve suspects who have amassed fortunes of billions or tens of millions of yuan, which they attempt to secretly move abroad via illegal channels. One focal point of the pursuit is recovering the money.

“Every country has different laws and specific operation with regards to recovering illicitly gained funds,” explains Liu Dong. “We have to review the local laws in almost every case. Therefore, they all take an extremely long time. Moreover, no case can be handled without abundant evidence. It is hard to check fraudulent gains and stolen sums without a suspect appearing before the court.”

Still, many countries including the United States, Singapore and Japan as well as the EU have signed law-bound agreements to split recovered assets.

“For instance, Australia enjoys the right to share forfeited assets after it succeeds in helping apprehend a foreign fugitive,” Zhuang remarks. Many countries initially refused to work with China without an agreement to split any recovered assets, and many cases suffered. In traditional Chinese concept, illicit money moved abroad still belongs to the state.

In Zhuangs perspective, splitting recovered money is a practical choice. On one hand, we must argue in line with the United Nations Convention against Corruption to refuse unreasonable demands, and on the other, we should refer to conventional international practices and provide some reimbursement to foreign countries for their assistance.

November 2014 brought the adoption of Beijing Declaration on Fighting Corruption during the APEC summit, aiming to establish a network to enforce laws to combat corruption, intensify pursuit of fugitives and recovery of ill-gotten money in the AsiaPacific region, and crack down on crossborder corruption. The promulgation of the Declaration has created a promising future for accelerating the negotiations of cooperation between China and other APEC member economies, including the United States, Canada, and Australia, in realms of extradition treaties, legal assistance, and curtailing money laundering.