Partnering With the Wolf

2015-03-12ByTangYuankai

By+Tang+Yuankai

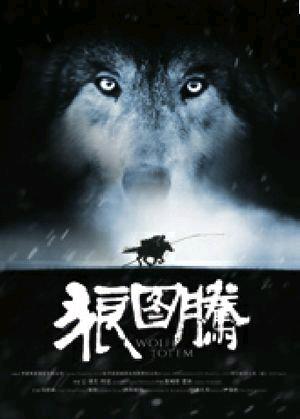

Back in 2008, French director Jean-Jacques Annaud returned to his home in France after wrapping up shooting in the Sahara. There, from a large number of books his friends had mailed to him, Annaud picked up Wolf Totem, a novel by a Chinese author, and was immediately drawn in. Soon after, Annaud unexpectedly received a phone call from China inviting him to direct a film adapted from the novel. Though at the same time he was also among the candidates for the big-budget Hollywood production Life of Pi, Annaud, who is known for making films with animals such as The Bear (1988) and Two Brothers (2004), decided to take up the offer from China.

After almost six years of shooting and pro- duction, Wolf Totem started to be screened throughout China on February 19, the Spring Festival of this year. Generally, the weeklong Spring Festival holiday is the most lucrative boxoffice period of the year in China when moviegoing peaks. French cinemas will release the film on April 25.

A hit book

The Chinese version of Wolf Totem, authored by Jiang Rong (penname) and first published in 2004, had been reprinted more than 150 times and had sold more than 5 million copies by the end of 2014. It has remained in Chinas top 10 bestselling novels for almost all of the past decade. Currently, the book is available in more than 110 countries and regions in 39 languages.

The bulk of the Wolf Totem story took place in the late 1960s in natural grassland of north Chinas Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, where local Mongolian herdsmen had to fight against wolves with every means available to prevent the fierce animals from preying on their livestock. Chen Zhen, the hero of the novel, was a young man from Beijing who volunteered to live and work in the grassland as an educated youth. In order to learn the wolfs behavior, Chen and his young friends caught a group of wolf cubs and raised one as a pet. In the process, he found that the wolf is an untamable and mysterious creature. Furthermore, he was astonished by the fact that Mongolian people regard the wolf as a spiritually important animal.

However, owing to poorly thought-out government policies, massive land reclamation in the grassland led to mass slaughtering of wolves. The shortsighted move severely damaged the local eco-system, resulting in rodent infestations and desertification in the following years. At the end of the novel, sandstorms from the Mongolia Plateau blanket Beijing and even affect Japan and South Korea across the sea.

In 2007, Jiang won the inaugural Man Asian Literary Prize—renamed the Asian Literary Prize in 2012—for Wolf Totem. Adrienne Clarkson, chair of the judges for the prize, praised Wolf Totem as a panoramic novel of life on the Mongolian grasslands. “This masterful work is also a passionate argument about the complex interrelationship between nomads and settlers, animals and human beings, nature and culture,” she said. “The slowly developing narrative is rendered in vivid detail and has a powerful cumulative effect. A book like no other. Memorable.”

Zhang Qiang, then General Manager of Beijing Forbidden City Film Co., bought the fiveyear motion picture rights to the novel in 2004. Unfortunately, all Chinese directors Zhang had contacted refused his invitation to adapt the book for the silver screen, as they felt it couldnt be done. Before the first contract expired, Zhang, still unwilling to give up, renewed it for another five years with a large sum of money. Finally, he contacted Annaud and entered into cooperation with the French director, who later revealed that he has had a keen curiosity in China since his childhood and has always been interested in grassland culture.

Annaud said that he became fascinated with the novel after just a few pages. He feels he shares similar life experiences and environmental protection ideas with the author. With maintaining man-nature harmony as his lifelong principle, Annaud said that he learned how to achieve it during his days in Africa years ago.

A movie

Nowadays, protecting grasslands and living in harmony with nature have become a consensus of the Chinese nation and been made a national policy. Annaud said that what impresses him the most is that the authors concerns about environmental deterioration have widely influenced the Chinese public amid the novels growing popularity.

The film Wolf Totem focuses on environmental problems because they are not only specific to China, Annaud said, adding that many EU members and the United States have also had to deal with these ongoing challenges. According to him, the film conveys a message about the importance of a harmonious coexistence between man and nature.

Both man and the wolf need a sound environment for survival, Annaud noted.

The original major storylines of the film were planned by Annaud and his long-time col- laborating French screenwriters. After that, he came to China and attempted to find a Chinese scriptwriter to partner with. His choice was Lu Wei, who wrote screenplays for two of the most famous Chinese films in recent history—Palme dOr-winning Farewell My Concubine in 1993 and To Live, which won the Grand Jury Prize at the Cannes International Film Festival in 1994. Noticeably, Lu himself also spent years living in a remote border area in China in his 20s. This made Annaud believed that Lu was able to fully understand and show the inner world of the hero of the film.

In the eyes of Zhang Xun, President of Beijing-based China Film Co-Production Corp., the model of cooperation between Annaud and Lu is ideal. Zhang Xun, who has been responsible for the global distribution of more than 300 Chinese and Chinese-foreign coproduced films, has always advocated that a co-production should begin with cooperation between Chinese and foreign moviemakers on the screenplays text. Only in this way, she said, can the completed film avoid problems arising from either foreigners limited knowledge about Chinas realities or Chinese peoples unfamiliarity with overseas audiences. An Australia-based screenwriter also participated in finalizing the screenplay for the film.

At the very beginning, Annaud and Jiang, the novels author, had reached an agreement that the film should feature real Mongolian wolves, instead of using computer-generated imagery. The director even insisted that real wolves should appear in 95 percent of the situations where they should be, in order to capture the authentic wildness of the animal.

In 2009, a training base up to international standards was established in Beijings suburban Shunyi District before the films shooting started, where more than 100 wolves were trained. Andrew Simpson, a world-class animal trainer from Canada, oversaw the work. Eventually, 20 of the centers trained wolves ended up in the film.

Feng Shaofeng, who played Chen Zhen in the film, was also allowed to raise and train the wolves, so that he could get acquainted with the animals. “Wolves will never accept humans as their master as dogs do; they treat us as friends,” Feng said.