好氧甲烷氧化菌生理生态特征及其在自然湿地中的群落多样性研究进展

2015-01-19邓永翠车荣晓吴伊波王艳芬崔骁勇

邓永翠, 车荣晓, 吴伊波, 王艳芬, 崔骁勇,*

1 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049 2 南京师范大学虚拟地理环境教育部重点实验室, 南京 210046 3 宁波大学, 宁波 315211

好氧甲烷氧化菌生理生态特征及其在自然湿地中的群落多样性研究进展

邓永翠1,2, 车荣晓1, 吴伊波3, 王艳芬1, 崔骁勇1,*

1 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049 2 南京师范大学虚拟地理环境教育部重点实验室, 南京 210046 3 宁波大学, 宁波 315211

甲烷氧化菌是一类可以利用甲烷作为唯一碳源和能源的细菌,在全球变化和整个生态系统碳循环过程中起着重要的作用。近年来,对甲烷氧化菌的生理生态特征及其在自然湿地中的群落多样性研究取得了较大进展。在分类方面,疣微菌门、NC10门及两个丝状菌属甲烷氧化菌的发现使其分类体系得到了进一步的完善;在单加氧酶方面,发现甲烷氧化菌可以利用pMMO和sMMO两种酶进行氧化甲烷的第一步反应,Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌中pMMO2的发现证实甲烷氧化菌可以利用这种酶氧化低浓度的甲烷;在底物利用方面,已经发现了越来越多的兼性营养型甲烷氧化菌,证实它们可以利用的底物比之前认为的更广泛,其中包括乙酸等含有碳碳键的化合物;在生存环境方面,能在不同温度、酸度和盐度的环境中生存的甲烷氧化菌不断被分离出来。全球自然湿地甲烷氧化菌群落多样性的研究目前主要集中在北半球高纬度的酸性泥炭湿地,Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌Methylocystis、Methylocella和Methylocapsa是这类湿地主要的甲烷氧化菌类群,尤其以Methylocystis类群最为广泛,而Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌尤其是Methylobacter在北极寒冷湿地中占优势。随着高通量测序时代的到来和新的分离技术的发展,对甲烷氧化菌的现有认识将面临更多的挑战和发展。

甲烷氧化菌; 甲烷; 甲烷单加氧酶; 湿地

甲烷是大气中辐射强迫仅次于二氧化碳的温室气体,大气中甲烷含量仅为二氧化碳的1/27,但单分子增温效应是二氧化碳的25倍,对全球温室效应的贡献率可达18%[1]。甲烷在大气中的浓度已经从工业化以前的体数分数为715×10-8增长到现在的体数分数为1770×10-8,这种增长是由其源汇平衡决定的。全球大气甲烷排放量约为500—600 Tg/a,其中自然湿地贡献总甲烷源的23%[2],是最大的大气甲烷源。自然湿地中厌氧土层产甲烷菌产生的甲烷大部分并没有直接进入大气,约90%的甲烷是通过湿地有氧土层的甲烷氧化菌消耗掉[3-4]。土壤里甲烷氧化菌的这种氧化作用是甲烷的唯一生物汇。甲烷氧化菌(Methanotrophs)在1906年首次被发现[5],它是甲基氧化菌(Methylotrophs)的一个分支,能利用甲烷(Methane,CH4)作为其唯一的碳源和能源[6]。甲烷氧化菌在全球变化和整个生态系统碳循环过程中起着非常重要的作用。现已有研究证实在各种生态环境中(湖泊底泥[7],水稻田[8],垃圾填埋场[9],泥炭湿地[10]及北极高纬度湿地[11]等)分布的甲烷氧化菌在消耗甲烷中起着重要的作用。

甲烷氧化菌的研究一直广受关注,在2009年之前,国际上几乎每4年就有一篇总结甲烷氧化菌研究进展的优秀综述发表,而在2009—2010年4篇综述论文刊载(表1)。这些综述主要关注甲烷氧化菌的分类、生理、生态分布、分离培养、应用、甲烷单加氧酶(Methane Monooxygenase,MMO)的催化机理等方面的研究和所用的研究技术等,但是缺少对甲烷氧化菌分布的重要生态系统——全球自然 湿地的详细综述;另外,关于近两年新发现的甲烷氧化菌的相关研究也还没有归纳在内。基于此,本文着重分析了全球自然湿地中好氧甲烷氧化菌多样性研究的现状,综述了好氧甲烷氧化菌的种类、氧化甲烷的关键酶及底物特征方面的新进展,并展望湿地甲烷氧化菌研究的发展趋势。

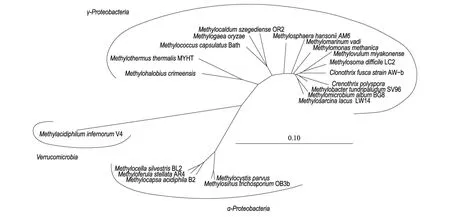

表1 国内外重要的甲烷氧化菌研究综述

1 甲烷氧化菌的分类及其生理生态特征研究进展

甲烷氧化菌(Methanotrophs)是甲基氧化菌(Methylotrophs)的一个分支,于1906年首次被发现[5],直到20世纪70年代,科学家才对其进行了广泛的分离和鉴定,使得详细的系统分类和生理研究得以进行[22]。迄今为止,已经发现了多种不同的甲烷氧化菌,并确定它们分别属于3个门:变形菌门(Proteobacteria)、疣微菌门(Verrucomicrobia)[23]和NC10门[24]。其中传统分类中的甲烷氧化菌都属于变形菌门,它们广泛分布在自然和人工生境中。疣微菌门的甲烷氧化菌迄今只分离到了3个菌株,都是从极端嗜酸嗜热环境中得到的,其中Acidimethylosilexfumarolicum来自意大利南部火山附近的沼泽土壤[25],Methylokorusinfernorum分离自新西兰的一个地热井[23],Methyloacidakamchatkensis是从俄罗斯的酸性温泉中分离到的[26],它们的最适生长温度都在55 ℃左右,并且能够在65 ℃下生长,被统一归为一个新属——Methylacidiphilum属[27]。NC10门甲烷氧化菌的代表菌株为Methylomirabilisoxyfera,能够在厌氧环境中同时进行甲烷氧化和反硝化作用[24,28],并产生其氧化甲烷所需要的氧气[29]。另外,根据利用甲烷时是否需要氧气的存在,可把甲烷氧化菌分为好氧甲烷氧化菌和厌氧甲烷氧化菌两类,本文以好氧甲烷氧化菌为对象,根据16S rRNA基因,构建了现阶段已发现的所有好氧甲烷氧化菌属的系统进化树(图1),清楚地表明了各好氧甲烷氧化菌分支之间的关系。

图1 利用21个好氧甲烷氧化菌属的16S rRNA基因构建的系统进化树

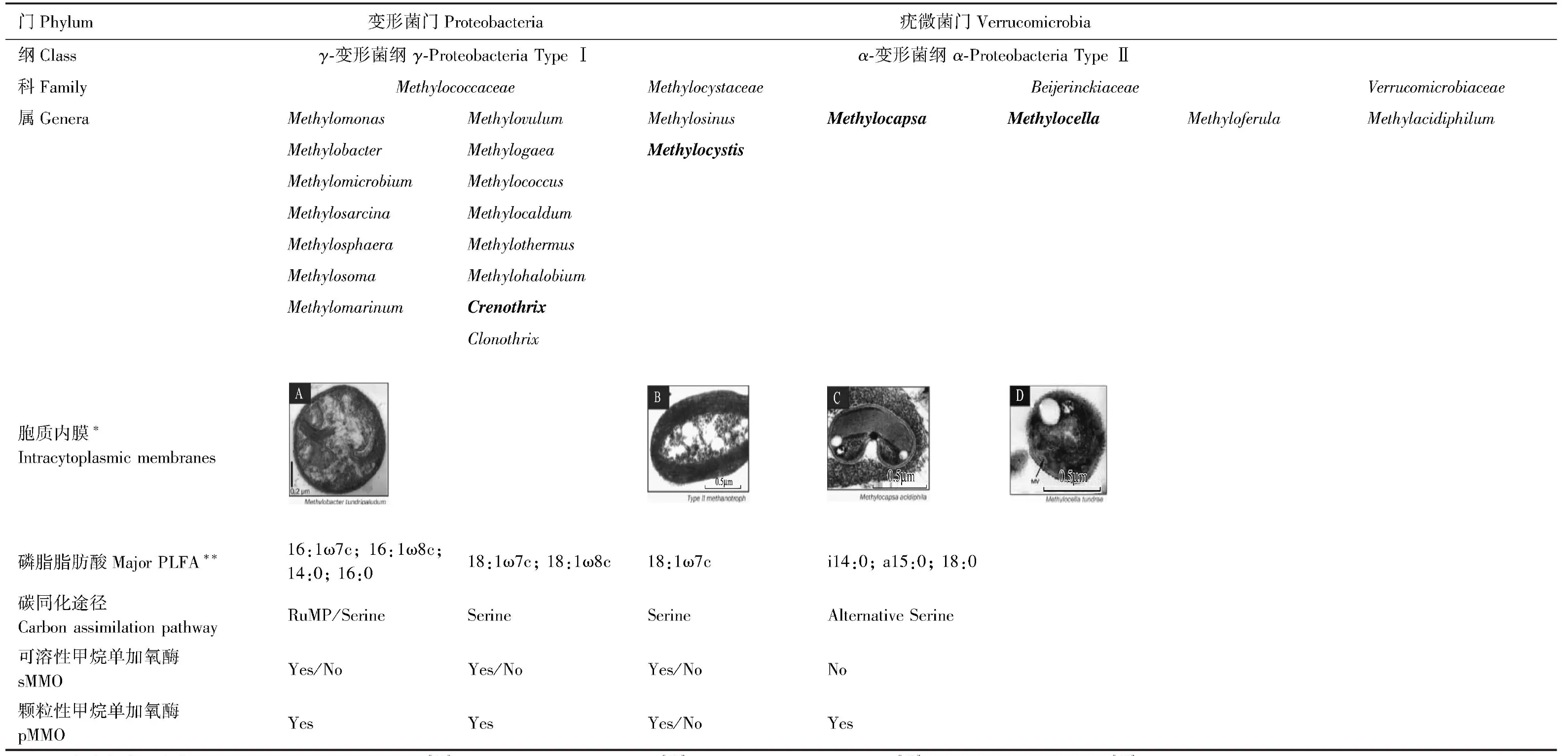

在甲烷氧化菌的3个门中,目前发现只有变形菌门的甲烷氧化菌存在于自然湿地中,而疣微菌门和NC10门的甲烷氧化菌在自然湿地中仍未检测到[30]。变形菌门的甲烷氧化菌可分为Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌和Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌,其中Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌属于γ-变形菌纲的Methylococcaceae科,现已发现了15个属(表2)。Ⅰ型又进一步分为Ⅰa型(如Methylobacter、Methylomicrobium、Methylomonas和Methylosarcina)和Ⅰb型(Methylococcus和Methylocaldum),Ⅰb型也就是之前命名为X型的甲烷氧化菌[15]。最近研究发现从海洋中分离到的Methylomarinum属[31]、从森林土壤中分离的Methylovulum属[32]以及水稻田中分离的Methylogaea属[33]都属于Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌。对存在于环境中尚不能纯培养的甲烷氧化菌,利用分子生物学手段检测其功能基因,显示一些包含部分特定功能基因序列的甲烷氧化菌类群也可归于Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌,如根据其提取环境而命名的RPC(Rice paddy cluster)、FW(Fresh water)和JRC(Japanese rice cluster)等[34]。此外还发现两类丝状甲烷氧化菌Crenothrixpolyspora[35]和Clonothrixfusca[36]也是Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌的一个独特分支。Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌属于α-变形菌纲,包括Methylocystaceae和Beijerinckiaceae两个科,前者有Methylocystis和Methylosinus属,后者有Methylocapsa、Methylocella和Methyloferula属(表2)。

Ⅰ型和Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌是根据其甲醛吸收和代谢途径、所含磷脂脂肪酸(Phospholipid Fatty Acid,PLFA)的类型以及细胞膜结构的差异等进行区分的。其中Ⅰa型甲烷氧化菌通过磷酸核酮糖途径(RuMP pathway)同化甲醛;Ⅰb型甲烷氧化菌既能通过RuMP途径,又同时包括低水平的丝氨酸途径(Serine pathway)同化甲醛[6],而且其生长温度比Ⅰa型和Ⅱ型高[15];Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌通过丝氨酸途径同化甲醛[21]。Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌的优势脂肪酸是14C和16C,而Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌的优势脂肪酸是18C[37],但也有一些甲烷氧化菌同时含有相当比例的16C和18C两种脂肪酸,如:Methylocystisheyeri(α-变形菌纲)、Methylohalobiuscrimeensis(γ-变形菌纲)和Methylothermusthermalis(γ-变形菌纲)同时含有Ⅰ型和Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌的标志性脂肪酸[38-40]。甲烷氧化菌的另一个分类特征是胞质内膜的排列方式(Intracytoplasmic membrane arrangments)不同。Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌具有成束的分布于细胞质内的胞质内膜,如表2-A中的Methylobactertundripaludum[41],而Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌Methylocystaceae科的Methylocystis和Methylosinus属的胞质内膜平行地延伸在细胞壁的周围(表2-B)[17]。Beijerinckiaceae科与Methylocystaceae科具有不同的胞质内膜结构,其中Methylocapsa属的胞质内膜平行分布于长轴细胞膜的一侧上[42](表2-C);Methylocella属的胞质内膜是由细胞质膜内陷形成的[43](表2-D);而Methyloferula没有发现胞质内膜结构[44]。

表2 好氧甲烷氧化菌的分类及其特征(根据Lüke[49]和Reim[50]改进,其中加粗的菌属代表兼性营养型甲烷氧化菌)

甲烷氧化菌利用甲烷的方式如下:首先由甲烷单加氧酶(MMO)将甲烷活化生成甲醇,再氧化为甲醛;然后通过丝氨酸途径或单磷酸核酮糖途径同化为细胞生物量,或者在氧化为甲酸后转变为二氧化碳。甲烷单加氧酶在这些过程中起关键性的作用,该酶存在两种形式:与膜结合、含有铜离子和铁离子的颗粒状甲烷单加氧酶(pMMO)和分泌在周质空间中的可溶性甲烷单加氧酶(sMMO)。在现已发现的好氧甲烷氧化菌中,除Methylocella和Methyloferla以外,都含有pMMO[44-45],而只在一些Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌(如Methylosinussp.[15])和几种Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌(如Methylomonassp.和Methylomicrobiumsp.)中能检测到编码sMMO的基因[46]。细胞中铜离子的浓度可以在转录水平上调节这两种单加氧酶的表达,当铜离子浓度小于0.8 μmol/L时, sMMO可以表达,当铜离子浓度大于4 μmol/L时,sMMO停止表达,只有pMMO表达,高浓度的铜离子浓度可以抑制sMMO基因的转录,而铜离子浓度的升高可以促进pMMO基因的转录。另外,铜离子是合成pMMO必须的金属元素。除了氧化甲烷外,pMMO还能氧化5个碳以内的一些短链化合物,sMMO则有更广泛的底物利用能力,能氧化种类多样的烷、烯和芳香族化合物[6]。

尽管16S rRNA基因是当今微生物生态研究中最普遍使用的标记基因,但是在研究具有特定功能的微生物类群时,需要采用更为专一的编码关键酶的基因(如pmoA基因和mmoX基因)替代16S rRNA基因。pmoA基因几乎存在于所有的甲烷氧化菌中,它编码关键酶pMMO的一个亚基,且基于pmoA基因和基于16S rRNA基因的甲烷氧化菌的系统发育关系有着很好的一致性,因此pmoA基因已经成为甲烷氧化菌生态学研究中广为采用的生物标记物[47]。相对于pmoA基因,编码sMMO的mmoX基因仅存在于少数种类的甲烷氧化菌中,对其研究也相对较少,近期在酸性泥炭湿地中的研究检测到了mmoX基因的表达[48],该基因在甲烷氧化菌研究中的应用开始受到更多的关注。

甲烷氧化菌对甲烷浓度需求的研究近年来取得了长足的进展,早期分离到的甲烷氧化菌都是对甲烷低亲和力的菌株,因此,在Baani等发现Methylocystissp. SC2菌除了含有pMMO外,还含有第2种甲烷单加氧酶(pMMO2)之前[51],人们一直认为甲烷氧化菌只能在高浓度甲烷下生存。甲烷氧化菌可在pMMO2酶的作用下氧化利用痕量的大气甲烷,而编码pMMO2的pmoA2基因在Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌Methylocystis和Methylosinus属中普遍存在,但在Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌中还没有发现[52]。上述研究结果表明大气中甲烷生物氧化的主要贡献者之一是Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌,尤其是Methylocystissp., 而之前一直认为山地和森林土壤中的一些未培养、高亲和力的甲烷氧化菌USCα和USCγ是吸收大气中低浓度甲烷的主要汇[53]。同时拥有对不同浓度甲烷源的可利用性和兼性营养的特性是Methylocystis属甲烷氧化菌在山地、森林[53]以及其它高浓度甲烷环境中广泛分布的主要原因之一。pMMO2的发现是对甲烷氧化菌研究的重要进展,对研究低甲烷浓度环境中的甲烷氧化菌有重要的指导作用,在这些环境中含有该酶的甲烷氧化菌可能占据优势。

对甲烷氧化菌底物专一性的研究也有新进展,Dedysh等发现从西伯利亚酸性泥炭湿地中分离到的3株Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌Methylocellapalustris,Methylocellasilvestris和Methylocellatundrae[54]既能把一碳化合物甲烷和甲醇作为其唯一的碳源和能源,又能利用多碳化合物,如有机酸(乙酸,丙酮酸,琥珀酸和苹果酸)和乙醇,作为其生长的唯一底物,证明了兼性营养型甲烷氧化菌的存在。属于γ-变形菌纲的新丝状甲烷氧化菌Crenothrixpolyspora在有甲烷存在的情况下能够利用乙酸,并且能少量吸收葡萄糖,表明该菌也是兼性营养型甲烷氧化菌[35]。但是另一种新近发现的丝状甲烷氧化菌Clonothrixfusca不能利用葡萄糖,该菌的16S rRNA基因序列与C.polyspora有密切的亲缘关系[36],这类甲烷氧化菌是否具有兼性营养的特性还需要更多的实验验证。近期还发现Methylocapsa属和Methylocystis属中的一些含有pMMO的甲烷氧化菌能利用乙酸作为唯一碳源[55-56]。这些研究结果显示甲烷氧化菌的底物利用能力并非和之前认为的那样单一,可能有更宽泛的底物类型。Semrau曾详细回顾了兼性营养型甲烷氧化菌的发现历史,并指出了今后可能的发展方向[57]。Dedysh对如何分离和鉴定兼性营养型甲烷氧化菌提出了很多指导和建议[58]。

对极端环境中的甲烷氧化菌的研究也取得了令人瞩目的进展。已发现的耐热或中度嗜热的甲烷氧化菌主要属于γ-变形菌纲的Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌,以及新发现的疣微菌门的3个菌株。在Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌Methylocaldum、Methylococcus和Methylothermus属中均发现有耐高温或嗜高温的甲烷氧化菌菌株[22,39,59],其中Methylocaldumtepidum和Methylocaldumgracile在47 ℃下可以存活,其最适生长温度为42 ℃;Methylocaldumszegendiense的最适生长温度为55 ℃[59];从日本一个温泉里分离到的Methylothermusthermalis的最适生长温度达57—59 ℃[39]。另一方面,也有一些甲烷氧化菌适应寒冷的环境[60],如Methylobacter属,无论是分离到的纯菌的最适生长温度[41]还是其大量存在于各种寒冷生境中(如:西伯利亚北极永冻土[61]和高海拔湿地[62]等)都表明它们适宜在低温环境中生存。从瑞典一处地下水中分离到的Methylomonasscandinavica[63]和从南极对流湖中分离到的Methylosphaerahansonii[64]也都属于嗜冷菌。在Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌的Methylocapsa属[42]和Methylocella属[43,45,65]中也有能在低温下生长的菌株。这些都表明在甲烷氧化菌的多个种属中比较广泛地分布有嗜冷或耐冷菌。

关于嗜酸性甲烷氧化菌的研究主要集中在北半球的酸性(pH 3.5—5.5)泥炭藓湿地,Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌Methylocystis、Methylocella和Methylocapsa属[56]是这类湿地的主要类群,它们都能在低pH环境下生长[18]。焦磷酸深度测序分析发现青藏高原的日干乔酸性泥炭湿地同样存在大量的Methylocystis[66]。在酸性泥炭湿地中也检测到了Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌Methylomomas[67]。新的嗜盐碱甲烷氧化菌也不断被分离到。生存于俄罗斯高盐碱性湖泊中的Methylomicrobium属甲烷氧化菌的最适生长pH为9.0—9.5[68-69],另一株分离到的嗜盐菌Methylohalobiuscrimeensis能在2.5 mol/L NaCl下存活,其最适生长盐度为1—1.5 mol/L NaCl[38]。分子方法检测也证明在一些高盐碱湖泊(如:Mono湖和Transbaikal湖)中有很多耐盐碱性或抗盐碱的甲烷氧化菌生存[70-71]。与此相对的是,Methylocella和Methylocapsa属的甲烷氧化菌只适宜在低盐浓度下生长[45,56],尤其是MethylocapsaKYG菌对盐浓度非常敏感,0.1% NaCl就可以抑制其生长速率的90%,0.2%—0.3% NaCl 完全抑制其生长[56]。

2 自然湿地甲烷氧化菌的研究进展

近年来,利用分子检测方法或者纯培养方法在全球自然湿地中开展了甲烷氧化菌的深入研究,总体情况见表3。

第一个用分子生物学方法研究湿地甲烷氧化菌的是英国Murrell小组的McDonald及其同事[72-73],他们使用16S rRNA和pmoA基因构建克隆文库,发现Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌,尤其是Methylocystis及Methylosinus,是酸性泥炭湿地主要的甲烷氧化菌。之后,该组的Chen等在酸性泥炭湿地甲烷氧化菌多样性方面的研究工作突出。他们使用DNA稳定性同位素与微阵列的方法,或者通过检测pmoA基因表达以及构建mmoX基因文库,进一步证实Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌,特别是其中的Methylocystis属,在酸性泥炭湿地的甲烷氧化菌中的优势地位[74-75],另外Methylocella和Methylocapsa也是泥炭湿地常见的类群[75]。虽然酸性泥炭湿地是以Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌为主的,但是在Moorhouse自然保护区湿地中也发现有Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌(如Methylobacter)存在[74]。

位于俄罗斯西伯利亚地区的酸性(pH 3.5—5.5)泥炭藓湿地是另一处甲烷氧化菌研究很多的地点[18,76-78]。该湿地主要的甲烷氧化菌属于α-变形菌纲,甲烷氧化菌的数量介于106—108个/g湿土之间[18,76-78]。在该湿地上还开展了大量的甲烷氧化菌分离培养的工作,已经分离得到了Methylocystis、Methylocella和Methylocapsa三个属的甲烷氧化菌菌株,这些也是该酸性泥炭湿地的主要甲烷氧化菌类群[42,45,54-56,79],它们都可以在pH<6的环境下生长[18]。

除了英国和俄罗斯之外,在欧洲大陆的西班牙、芬兰、荷兰、德国以及挪威的北极地区都有对甲烷氧化菌群落结构的研究。这些研究大部分是在泥炭藓湿地上开展的,只有少数关注到森林泥炭湿地和河流湿地土壤中的甲烷氧化菌。研究表明位于寒冷地区的挪威和芬兰湿地Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌比例更高[11,80],尤其是Methylobacter,在北极湿地中用变形梯度凝胶电泳(DGGE)和稳定性同位素探针(SIP)的方法都检测到该菌的存在[11,81],当然在这些研究地点还同时检测到了Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌[48,80-83]。另外,Kip从荷兰泥炭藓湿地植物中分离到了一株Methylomomas属的甲烷氧化菌,这是第一株嗜酸的γ-变形菌纲的甲烷氧化菌[67],在这之前,从没有在酸性泥炭湿地中分离到属于γ-变形菌纲的甲烷氧化菌。

除欧洲大陆以外,在美国和日本的自然湿地中也开展了甲烷氧化菌的研究,研究集中在泥炭湿地上,植被类型除泥炭藓外,还包括莎草科植被和森林湿地。与英国和俄罗斯的泥炭藓湿地以Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌为主不同,在这些地区Ⅰ型和Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌都广泛存在,有的样地主要是Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌,有的样地Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌占优。直到2012年,在自然湿地上开展的甲烷氧化菌群落多样性的所有研究都集中在北半球,该年Kip小组将这项工作推进到了南半球,他们用分子生物学方法,研究发现高丰度的Methylocystis属甲烷氧化菌可能是南半球泥炭藓湿地甲烷氧化的主要贡献者[84]。

我国幅员辽阔,自然湿地类型多样。但对我国自然湿地甲烷氧化菌的研究一直是空白,直到2010年才在位于青藏高原的若尔盖湿地开展了初步的研究[62]。青藏高原作为全球海拔最高的一个独特地域,其湿地众多,面积约为13.3×l04km2,每年从青藏高原湿地排放的甲烷约为0.56—1 Tg[85-86],除了若尔盖湿地之外,青藏高原的其它自然湿地也是甲烷排放的主要源。近期在位于红原的日干乔湿地对甲烷氧化菌群落多样性和活性甲烷氧化菌类进行了较系统的研究[66]。另外,在位于松嫩平原的向海湿地上也有关于甲烷氧化菌的丰度和多样性随土壤深度变化的研究发表[87]。

3 结论与展望

随着分子生物学和分离培养技术的发展,对甲烷氧化菌的认识不断深入。研究表明甲烷氧化菌的多样性比之前想象的要多,但是大部分环境中主要的好氧甲烷氧化菌属于变形菌门,可根据其生理特性分为Ⅰ型和Ⅱ型两类甲烷氧化菌。甲烷氧化菌可以利用pMMO和sMMO两种酶进行氧化甲烷的第一步反应。pMMO2的发现表明Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌中有些类群可以利用这种酶氧化低浓度的甲烷。新研究证实甲烷氧化菌可以利用的底物比之前认为的更广泛,包括乙酸等含有碳碳键的化合物。另外,从极端环境中发现的各种嗜冷、嗜热、嗜酸、嗜碱和嗜盐的甲烷氧化菌表明甲烷氧化菌广泛分布在各种生态环境中。

目前对甲烷氧化菌多样性的研究主要集中在酸性泥炭湿地,尤其是位于北半球高纬度的酸性泥炭藓湿地。研究表明Ⅱ型甲烷氧化菌Methylocystis、Methylocella和Methylocapsa是这类湿地主要的甲烷氧化菌类群,尤其是Methylocystis,广泛分布在酸性泥炭湿地中。在北极寒冷的湿地中,Ⅰ型甲烷氧化菌占优势,其中Methylobacter大量存在。我国对自然湿地甲烷氧化菌的研究还处于起步阶段,但也取得了一些有价值的研究结果。

随着高通量测序时代的到来和纯培养技术的不断发展,更多的在极端环境中生存的甲烷氧化菌会被发现,将不断完善人们对甲烷氧化菌生理和生态适应性的认识。同时,新的甲烷氧化菌类群的不断发现,会挑战现有甲烷氧化菌的分类方法;特别是随着海量序列数据的出现,必将发现更多新的甲烷氧化菌序列和新的甲烷氧化菌菌株,整个分类系统是否需要做较大幅度的修改还属未知。另外,先进的分子生物学技术也给甲烷氧化菌的生物地理学研究提供了有力的工具,随着在全球更多生态环境中对甲烷氧化菌研究的积累,其群落结构及其多样性特征是否存在有规律的地理格局等重要生物地理学问题的答案将变得逐渐清晰。

表3 自然湿地甲烷氧化菌多样性研究概况

[1] Forster P. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC. Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Chen Z, Marquis M, Averyt K B, Tignor M, Miller H L, eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

[2] Conrad R. The global methane cycle: recent advances in understanding the microbial processes involved. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2009, 1(5): 285-292.

[3] Shannon R D, White J R, Lawson J E, Gilmour B S. Methane efflux from emergent vegetation in peatlands. The Journal of Ecology, 1996, 84(2): 239-246.

[4] Hornibrook E R C, Bowes H L, Culbert A, Gallego-Sala A V. Methanotrophy potential versus methane supply by pore water diffusion in peatlands. Biogeosciences, 2009, 6(8): 1491-1504.

[5] Söhngen N L. Uber bakterien, welche methan ab kohlenstoffnahrung and energiequelle gebrauchen. Parasitenkd Infectionskr Abt, 1906, 15: 513-517.

[6] Trotsenko Y A, Murrell J C. Metabolic aspects of aerobic obligate methanotrophy. Advances in Applied Microbiology, 2008, 63: 183-229.

[7] Dumont M G, Pommerenke B, Casper P, Conrad R. DNA-, rRNA-and mRNA-based stable isotope probing of aerobic methanotrophs in lake sediment. Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 13(5): 1153-1167.

[8] Qiu Q F, Noll M, Abraham W R, Lu Y H, Conrad R. Applying stable isotope probing of phospholipid fatty acids and rRNA in a Chinese rice field to study activity and composition of the methanotrophic bacterial communities in situ. Isme Journal, 2008, 2(6): 602-614.

[9] Chen Y, Dumont M G, Cébron A, Murrell J C. Identification of active methanotrophs in a landfill cover soil through detection of expression of 16S rRNA and functional genes. Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 9(11): 2855-2869.

[10] Kip N, van Winden J F, Pan Y, Bodrossy L, Reichart G J, Smolders A J P, Jetten M S M, Damsté J S S, Op den Camp H J M. Global prevalence of methane oxidation by symbiotic bacteria in peat-moss ecosystems. Nature Geoscience, 2010, 3(9): 617-621.

[11] Graef C, Hestnes A G, Svenning M M, Frenzel P. The active methanotrophic community in a wetland from the High Arctic. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2011, 3(4): 466-472.

[12] 梁战备, 史奕, 岳进. 甲烷氧化菌研究进展. 生态学杂志, 2004, 23(5): 198-205.

[13] 韩冰, 苏涛, 李信, 邢新会. 甲烷氧化菌及甲烷单加氧酶的研究进展. 生物工程学报, 2008, 24(9): 1511-1519.

[14] 佘晨兴, 仝川. 自然湿地土壤产甲烷菌和甲烷氧化菌多样性的分子检测. 生态学报, 2011, 31(14): 4126-4135.

[15] Hanson R S, Hanson T E. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiological Reviews, 1996, 60(2): 439-471.

[16] Bowman J. The methanotrophs. The families methylococcaceae and methylocystaceae // Dworkin M, ed. The Prokaryotes. New York: Springer, 2006: 266-289.

[17] Dalton H. The Leeuwenhoek Lecture 2000 The natural and unnatural history of methane-oxidizing bacteria. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2005, 360(1458): 1207-1222.

[18] Dedysh S N. Exploring methanotroph diversity in acidic northern wetlands: molecular and cultivation-based studies. Microbiology, 2009, 78(6): 655-669.

[19] Chen Y, Murrell J C. Ecology of aerobic methanotrophs and their role in methane cycling // Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology. Heidelberg: Springer. 2010: 3067-3076.

[20] Murrell J C. The aerobic methane oxidizing bacteria//Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology. Heidelberg: Springer. 2010: 1954-1966.

[21] Semrau J D, DiSpirito A A, Yoon S. Methanotrophs and copper. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2010, 34(4): 496-531.

[22] Whittenbury R, Philips K C, Wilkinson J F. Enrichment, isolation and some properties of methane-utilizing bacteria. Journal of General Microbiology, 1970, 61(2): 205-218.

[23] Dunfield P F, Yuryev A, Senin P, Smirnova A V, Stott M B, Hou S, Ly B, Saw J H, Zhou Z M, Ren Y, Wang J M, Mountain B W, Crowe M A, Weatherby T M, Bodelier P L E, Liesack W, Feng L, Wang L, Alam M. Methane oxidation by an extremely acidophilic bacterium of the phylum Verrucomicrobia. Nature, 2007, 450(7171): 879-882.

[24] Ettwig K F, Butler M K, Le Paslier D, Pelletier E, Mangenot S, Kuypers M M M, Schreiber F, Dutilh B E, Zedelius J, de Beer D, Gloerich J, Wessels H J C T, van Alen T, Luesken F, Wu M L, van de Pas-Schoonen K, Op den Camp H J M, Janssen-Megens E M, Francoijs K J, Stunnenberg H, Weissenbach J, Jetten M S M, Strous M. Nitrite-driven anaerobic methane oxidation by oxygenic bacteria. Nature, 2010, 464(7288): 543-548.

[25] Pol A, Heijmans K, Harhangi H R, Tedesco D, Jetten M S M, Op den Camp H J M. Methanotrophy below pH1 by a new Verrucomicrobia species. Nature, 2007, 450(7171): 874-878.

[26] Islam T, Jensen S, Reigstad L J, Larsen Ø, Birkeland N K. Methane oxidation at 55℃ and pH2 by a thermoacidophilic bacterium belonging to the Verrucomicrobia phylum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(1): 300-304.

[27] Op den Camp H J M, Islam T, Stott M B, Harhangi H R, Hynes A, Schouten S, Jetten M S M, Birkeland N K, Pol A, Dunfield P F. Environmental, genomic and taxonomic perspectives on methanotrophicVerrucomicrobia. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2009, 1(5): 293-306.

[28] Ettwig K F, van Alen T, van de Pas-Schoonen K, Jetten M S M, Strous M. Enrichment and molecular detection of denitrifying methanotrophic bacteria of the NC10 phylum. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2009, 75(11): 3656-3662.

[29] Strous M. Beyond denitrification: alternative routes to dinitrogen // Nitrogen Cycling in Bacteria: Molecular Analysis. Norfolk, UK: Caister Academic Press, 2011: 123-133.

[30] Kolb S, Horn M A. Microbial CH4and N2O consumption in acidic wetlands. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2012, 3: 78.

[31] Hirayama H, Fuse H, Abe M, Miyazaki M, Nakamura T, Nunoura T, Furushima Y, Yamamoto H, Takai K.Methylomarinumvadigen. nov., sp. nov., a methanotroph isolated from two distinct marine environments. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2013, 63(Pt 3): 1073-1082.

[32] Iguchi H, Yurimoto H, Sakai Y.Methylovulummiyakonensegen. nov., sp. nov., a type I methanotroph isolated from forest soil. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2011, 61(4): 810-815.

[33] Geymonat E, Ferrando L, Tarlera S E.Methylogaeaoryzaegen. nov., sp nov., a mesophilic methanotroph isolated from a rice paddy field. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2011, 61(11): 2568-2572.

[34] Lüke C, Frenzel P. Potential ofpmoAamplicon pyrosequencing for methanotroph diversity studies. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 77(17): 6305-6309.

[35] Stoecker K, Bendinger B, Schöning B, Nielsen P H, Nielsen J L, Baranyi C, Toenshoff E R, Daims H, Wagner M. Cohn′sCrenothrixis a filamentous methane oxidizer with an unusual methane monooxygenase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006, 103(7): 2363-2367.

[36] Vigliotta G, Nutricati E, Carata E, Tredici S M, De Stefano M, Pontieri P, Massardo D R, Prati M V, De Bellis L, Alifano P.ClonothrixfuscaRoze 1896, a filamentous, sheathed, methanotrophic γ-proteobacterium. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 73(11): 3556-3565.

[37] Bodelier P L E, Gillisen M J B, Hordijk K, Damsté J S S, Rijpstra W I C, Geenevasen J A J, Dunfield P F. A reanalysis of phospholipid fatty acids as ecological biomarkers for methanotrophic bacteria. ISME Journal, 2009, 3(5): 606-617.

[38] Heyer J, Berger U, Hardt M, Dunfield P F.Methylohalobiuscrimeensisgen. nov., sp. nov., a moderately halophilic, methanotrophic bacterium isolated from hypersaline lakes of Crimea. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2005, 55(5): 1817-1826.

[39] Tsubota J, Eshinimaev B T, Khmelenina V N, Trotsenko Y A.Methylothermusthermalisgen. nov., sp. nov., a novel moderately thermophilic obligate methanotroph from a hot spring in Japan. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2005, 55(5): 1877-1884.

[40] Dedysh S N, Belova S E, Bodelier P L E, Smirnova K V, Khmelenina V N, Chidthaisong A, Trotsenko Y A, Liesack W, Dunfield P F.Methylocystisheyerisp nov., a novel type Ⅱ methanotrophic bacterium possessing ‘signature’ fatty acids of type I methanotrophs. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2007, 57(3): 472-479.

[41] Wartiainen I, Hestnes A G, McDonald I R, Svenning M M.Methylobactertundripaludumsp. nov., a methane-oxidizing bacterium from Arctic wetland soil on the Svalbard islands, Norway (78°N). International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2006, 56(Part 1): 109-113.

[42] Dedysh S N, Khmelenina V N, Suzina N E, Trotsenko Y A, Semrau J D, Liesack W, Tiedje J M.Methylocapsaacidiphilagen. nov., sp. nov., a novel methane-oxidizing and dinitrogen-fixing acidophilic bacterium fromSphagnumbog. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2002, 52(Part 1): 251-261.

[43] Dedysh S N, Berestovskaya Y Y, Vasylieva L V, Belova S E, Khmelenina V N, Suzina N E, Trotsenko Y A, Liesack W, Zavarzin G A.Methylocellatundraesp. nov., a novel methanotrophic bacterium from acidic tundra peatlands. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2004, 54(1): 151-156.

[44] Vorobev A V, Baani M, Doronina N V, Brady A L, Liesack W, Dunfield P F, Dedysh S N.Methyloferulastellatagen. nov., sp. nov., an acidophilic, obligately methanotrophic bacterium that possesses only a soluble methane monooxygenase. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2011, 61(10): 2456-2463.

[45] Dedysh S N, Liesack W, Khmelenina V N, Suzina N E, Trotsenko Y A, Semrau J D, Bares A M, Panikov N S, Tiedje J M.Methylocellapalustrisgen. nov., sp. nov., a new methane-oxidizing acidophilic bacterium from peat bogs, representing a novel subtype of serine-pathway methanotrophs. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2000, 50(3): 955-969.

[46] Auman A J, Stolyar S, Costello A M, Lidstrom M E. Molecular characterization of methanotrophic isolates from freshwater lake sediment. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2000, 66(12): 5259-5266.

[47] Dumont M G, Murrell J C. Community-level analysis: key genes of aerobic methane oxidation. Environmental Microbiology, 2005, 397: 413-427.

[48] Liebner S, Svenning M M. Environmental transcription ofmmoXby methane oxidizingProteobacteriain a Subarctic palsa peatland. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2013, 79(2): 701-706.

[49] Lüke C. Molecular Ecology and Biogeography of Methanotrophic Bacteria in Wetland Rice Fields [D]. Marburg: Philipps-Universität, 2010.

[50] Reim A. Methane Oxidizing Bacteria at the Oxic-anoxic Interface: Taxon-specific Activity and Resilience [D]. Marburg: Philipps-Universität, 2013.

[51] Baani M, Liesack W. Two isozymes of particulate methane monooxygenase with different methane oxidation kinetics are found inMethylocystissp. strain SC2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(29): 10203-10208.

[52] Yimga M T, Dunfield P F, Ricke P, Heyer J, Liesack W. Wide distribution of a novelpmoA-like gene copy among type Ⅱ methanotrophs, and its expression inMethylocystisstrain SC2. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(9): 5593-5602.

[53] Knief C, Lipski A, Dunfield P F. Diversity and activity of methanotrophic bacteria in different upland soils. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(11): 6703-6714.

[54] Dedysh S N, Knief C, Dunfield P F.Methylocellaspecies are facultatively methanotrophic. Journal of Bacteriology, 2005, 187(13): 4665-4670.

[55] Belova S E, Baani M, Suzina N E, Bodelier P L E, Liesack W, Dedysh S N. Acetate utilization as a survival strategy of peat-inhabitingMethylocystisspp. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2011, 3(1): 36-46.

[56] Dunfield P F, Belova S E, Vorob′ev A V, Cornish S L, Dedysh S N.Methylocapsaaureasp. nov., a facultative methanotroph possessing a particulate methane monooxygenase, and emended description of the genusMethylocapsa. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2010, 60(11): 2659-2664.

[57] Semrau J D, DiSpirito A A, Vuilleumier S. Facultative methanotrophy: false leads, true results, and suggestions for future research. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2011, 323(1): 1-12.

[58] Dedysh S N, Dunfield P F. Facultative and obligate methanotrophs: how to identify and differentiate them. Methods in Enzymology, 2011, 495: 31-44.

[59] Bodrossy L, Holmes E M, Holmes A J, Kovács K L, Murrell J C. Analysis of 16S rRNA and methane monooxygenase gene sequences reveals a novel group of thermotolerant and thermophilic methanotrophs,Methylocaldumgen. nov. Archives of Microbiology, 1997, 168(6): 493-503.

[60] Trotsenko Y A, Khmelenina V N. Aerobic methanotrophic bacteria of cold ecosystems. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2005, 53(1): 15-26.

[61] Liebner S, Rublack K, Stuehrmann T, Wagner D. Diversity of aerobic methanotrophic bacteria in a permafrost active layer soil of the Lena Delta, Siberia. Microbial Ecology, 2009, 57(1): 25-35.

[62] Yun J L, Zhuang G Q, Ma A Z, Guo H G, Wang Y F, Zhang H X. Community structure, abundance, and activity of methanotrophs in the Zoige Wetland of the Tibetan Plateau. Microbial Ecology, 2012, 63(4): 835-843.

[63] Kalyuzhnaya M G, Khmelenina V N, Kotelnikova S, Holmquist L, Pedersen K, Trotsenko Y A.Methylomonasscandinavicasp. nov., a new methanotrophic psychrotrophic bacterium isolated from deep igneous rock ground water of Sweden. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 1999, 22(4): 565-572.

[64] Bowman J P, McCammon S A, Skerrat J H. Methylosphaera hansonii gen. nov., sp. nov., a psychrophilic, group I methanotroph from Antarctic marine-salinity, meromictic lakes. Microbiology, 1997, 143(4): 1451-1459.

[65] Dunfield P F, Khmelenina V N, Suzina N E, Trotsenko Y A, Dedysh S N.Methylocellasilvestrissp. nov., a novel methanotroph isolated from an acidic forest cambisol. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2003, 53(5): 1231-1239.

[66] Deng Y C, Cui X Y, Lüke C, Dumont M G. Aerobic methanotroph diversity in Riganqiao peatlands on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2013, 5(4): 566-574.

[67] Kip N, Ouyang W J, van Winden J, Raghoebarsing A, van Niftrik L, Pol A, Pan Y, Bodrossy L, van Donselaar E G, Reichart G J, Jetten M S M, Damste J S S, Op den Camp H J M. Detection, isolation, and characterization of acidophilic methanotrophs fromSphagnummosses. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 77(16): 5643-5654.

[68] Khmelenina V N, Kalyuzhnaya M G, Starostina N G, Suzina N E, Trotsenko Y A. Isolation and characterization of halotolerant alkaliphilic methanotrophic bacteria from Tuva soda lakes. Current Microbiology, 1997, 35(5): 257-261.

[69] Kalyuzhnaya M G, Khmelenina V, Eshinimaev B, Sorokin D, Fuse H, Lidstrom M, Trotsenko Y. Classification of halo(alkali)philic and halo(alkali)tolerant methanotrophs provisionally assigned to the generaMethylomicrobiumandMethylobacterand emended description of the genusMethylomicrobium. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2008, 58(3): 591-596.

[70] Lin J L, Joye S B, Scholten J C M, Schäfer H, McDonald I R, Murrell J C. Analysis of methane monooxygenase genes in mono lake suggests that increased methane oxidation activity may correlate with a change in methanotroph community structure. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2005, 71(10): 6458-6462.

[71] Lin J L, Radajewski S, Eshinimaev B T, Trotsenko Y A, McDonald I R, Murrell J C. Molecular diversity of methanotrophs in Transbaikal soda lake sediments and identification of potentially active populations by stable isotope probing. Environmental Microbiology, 2004, 6(10): 1049-1060.

[72] McDonald I R, Hall G H, Pickup R W, Murrell J C. Methane oxidation potential and preliminary analysis of methanotrophs in blanket bog peat using molecular ecology techniques. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 1996, 21(3): 197-211.

[73] McDonald I R, Murrell J C. The particulate methane monooxygenase genepmoAand its use as a functional gene probe for methanotrophs. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 1997, 156(2): 205-210.

[74] Chen Y, Dumont M G, McNamara N P, Chamberlain P M, Bodrossy L, Stralis-Pavese N, Murrell J C. Diversity of the active methanotrophic community in acidic peatlands as assessed by mRNA and SIP-PLFA analyses. Environmental Microbiology, 2008, 10(2): 446-459.

[75] Chen Y, Dumont M G, Neufeld J D, Bodrossy L, Stralis-Pavese N, McNamara N P, Ostle N, Briones M J I, Murrell J C. Revealing the uncultivated majority: combining DNA stable-isotope probing, multiple displacement amplification and metagenomic analyses of uncultivatedMethylocystisin acidic peatlands. Environmental Microbiology, 2008, 10(10): 2609-2622.

[76] Dedysh S N. Methanotrophic bacteria of acidicSphagnumpeat bogs. Microbiology, 2002, 71(6): 638-650.

[77] Dedysh S N, Derakshani M, Liesack W. Detection and enumeration of methanotrophs in acidicSphagnumpeat by 16S rRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization, including the use of newly developed oligonucleotide probes forMethylocellapalustris. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2001, 67(10): 4850-4857.

[78] Dedysh S N, Dunfield P F, Derakshani M, Stubner S, Heyer J, Liesack W. Differential detection of type Ⅱ methanotrophic bacteria in acidic peatlands using newly developed 16S rRNA-targeted fluorescent oligonucleotide probes. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2003, 43(3): 299-308.

[79] Dedysh S N, Panikov N S, Liesack W, Groβkopf R, Zhou J Z, Tiedje J M. Isolation of acidophilic methane-oxidizing bacteria from northern peat wetlands. Science, 1998, 282(5387): 281-284.

[80] Jaatinen K, Tuittila E S, Laine J, Yrjala K, Fritze H. Methane-oxidizing bacteria in a Finnish raised mire complex: Effects of site fertility and drainage. Microbial Ecology, 2005, 50(3): 429-439.

[81] Wartiainen I, Hestnes A G, Svenning M M. Methanotrophic diversity in high arctic wetlands on the islands of svalbard (Norway)-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of soil DNA and enrichment cultures. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 2003, 49(10): 602-612.

[82] Siljanen H M P, Saari A, Krause S, Lensu A, Abell G C J, Bodrossy L, Bodelier P L E, Martikainen P J. Hydrology is reflected in the functioning and community composition of methanotrophs in the littoral wetland of a boreal lake. Fems Microbiology Ecology, 2011, 75(3): 430-445.

[83] Siljanen H M P, Saari A, Bodrossy L, Martikainen P J. Seasonal variation in the function and diversity of methanotrophs in the littoral wetland of a boreal eutrophic lake. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2012, 80(3): 548-555.

[84] Kip N, Fritz C, Langelaan E S, Pan Y, Bodrossy L, Pancotto V, Jetten M S M, Smolders A J P, Op den Camp H J M. Methanotrophic activity and diversity in differentSphagnummagellanicumdominated habitats in the southernmost peat bogs of Patagonia. Biogeosciences, 2012, 9(1): 47-55.

[85] Jin H J, Wu J, Cheng G D, Nakano T, Sun G Y. Methane emissions from wetlands on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Chinese Science Bulletin, 1999, 44(24): 2282-2286.

[86] Ding W X, Cai Z C. Methane emission from natural wetlands in China: summary of years 1995—2004 studies. Pedosphere, 2007, 17(4): 475-486.

[87] Yun J L, Yu Z S, Li K, Zhang H X. Diversity, abundance and vertical distribution of methane-oxidizing bacteria (methanotrophs) in the sediments of the Xianghai wetland, Songnen Plain, northeast China. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 2013, 13(1): 242-252.

[88] Bodelier P L E, Meima-Franke M, Zwart G, Laanbroek H J. New DGGE strategies for the analyses of methanotrophic microbial communities using different combinations of existing 16S rRNA-based primers. Fems Microbiology Ecology, 2005, 52(2): 163-174.

[89] Kip N, Dutilh B E, Pan Y, Bodrossy L, Neveling K, Kwint M P, Jetten M S M, Op den Camp H J M. Ultra-deep pyrosequencing ofpmoAamplicons confirms the prevalence ofMethylomonasandMethylocystisinSphagnummosses from a Dutch peat bog. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2011, 3(6): 667-673.

[90] Narihiro T, Hori T, Nagata O, Hoshino T, Yumoto I, Kamagata Y. The impact of aridification and vegetation type on changes in the community structure of methane-cycling microorganisms in Japanese wetland soils. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 2011, 75(9): 1727-1734.

[91] Miller D N, Yavitt J B, Madsen E L, Ghiorse W C. Methanotrophic activity, abundance, and diversity in forested swamp pools: spatiotemporal dynamics and influences on methane fluxes. Geomicrobiology Journal, 2004, 21(4): 257-271.

[92] Gupta V, Smemo K A, Yavitt J B, Basiliko N. Active methanotrophs in two contrasting North American peatland ecosystems revealed using DNA-SIP. Microbial Ecology, 2012, 63(2): 438-445.

[93] Yun J L, Ma A Z, Li Y M, Zhuang G Q, Wang Y F, Zhang H X. Diversity of methanotrophs in Zoige wetland soils under both anaerobic and aerobic conditions. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2010, 22(8): 1232-1238.

A review of the physiological and ecological characteristics of methanotrophs and methanotrophic community diversity in the natural wetlands

DENG Yongcui1,2, CHE Rongxiao1, WU Yibo3, WANG Yanfen1, CUI Xiaoyong1,*

1UniversityofChineseAcademyofSciences,Beijing100049,China2KeyLaboratoryofVirtualGeographicEnvironment,MinistryofEducation,NanjingNormalUniversity,Nanjing210046,China3NingboUniversity,Ningbo315211,China

Methanotrophs are a group of bacteria that can use methane as their sole source of carbon and energy. They play a major role in carbon cycle and global warming by controlling emissions of methane, the second most important greenhouse gas following CO2. In this review, we summarize recent progress on the physiology, phylogeny, and ecology of methanotrophs, with particular focus on the diversity of methanotrophic community in natural wetlands. The traditionally identified methanotrophs all belong to the phylumProteobacteria. Based on intracytoplasmic membranes formation, predominant fatty acid types, the mechanism by which carbon is assimilated into biomass and phylogenetic characteristics, proteobacterial methanotrophs are divided into two groups, type Ⅰ and type Ⅱ (Gamma-andAlpha-proteobacteria, respectively). Up to now, 20 methanotrophic genera have been affiliated in phylumProteobacteria, including two filamentous methanotrophs,CrenothrixpolysporaandClonothrixfusca. These two species have been characterized recently and form a new branch within the familyMethylococcaceae. Verrucomicrobial methanotrophs, a remarkable new finding, are distantly related to the proteobacteria methanotrophs. They have been isolated from geothermal sites, seem to be restricted to extreme environments and form a new genus (Methylacidiphilum). Methanotrophs are also found in a novel phylum named NC10, which represents bacteria capable of aerobic methane oxidation coupled to denitrification under anoxic conditions. Two types of enzyme, a particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO) and a soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO) can be used by methanotrophs to execute the first step of methane oxidation. All known methanotrophs possess the pMMO, except generaMethylocellaandMethyloferulawhich only have sMMO. Some methanotrophs of type Ⅰ and Ⅱ have both pMMO and sMMO. A different pMMO (pMMO2) is discovered in some type Ⅱ methanotrophs. pMMO2 has lower methane oxidation kinetics and enables these methanotrophs to consume methane at atmospheric concentrations. ThepmoAandmmoXgene, encoding subunits of the pMMO and sMMO respectively, have been used as a functional marker for detecting methanotrophs in environmental samples. However, the current publicpmoAsequences database is larger than that of themmoX, and the sequence basedpmoAphylogeny has good correlation to the 16S rRNA phylogeny. Facultative methanotrophs have been reported in the generaMethylocella,Methylocapsa, andMethylocystis. Some species of them can use compounds with carbon-carbon bonds as sole growth substrates, including acetate, large organic acids or ethanol. These findings broke the traditional notion that methanotrophs could only use one-carbon compounds, indicating that broader substrate utilization might be more common in methanotrophs. Methanotrophs have been isolated from various environments including habitats of extreme temperature, acidity or salinity. For example, some type Ⅰ methanotrophs (Methylocaldum,Methylococcus, andMethylothermus) were reported to have optimum growth temperatures above 40 ℃. On the other hand there are some methanotrophs (MethylobacterandMethylocella) adapted to cold environments and with optimum growth temperatures of 0—30 ℃. SomeMethylacidiphilumspecies grow at extreme low pH of 2—2.5. But someMethylomicrobiumspecies have the optimum pH of 9.0—9.5. Besides, someMethylomicrobiumspecies andMethylohalobiuscrimeensisare halotolerant methanotrophs and have a growth optimum around 1—1.5 mol/L NaCl. In contrast,MethylocapsaKYG is very sensitive to NaCl and can only grow at low NaCl concentrations. By employing the 16S rRNA gene or functional genes as molecular markers, the methanotrophic communities have been extensively studied in many natural wetlands. A variety of molecular biological tools, such as T-RFLP, DGGE, FISH, clone library and pyrosequencing, have been used to detect the community diversity of methanotrophs in soils of these ecosystems. Most of the studies were conducted in acidic peat wetlands at the high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, especially in the United Kingdom and Russian. In these peatlands, most of the known methanotrophs belonged to type Ⅱ, such as generaMethylocystis,MethylocellaandMethylocapsa. Especially genusMethylocystis, were widely distributed in acidic peatlands. Type Ⅰ methanotrophs, especially genusMethylobacter, were dominant in the cold Arctic wetlands in Norway and Finland. Furthermore, researches revealed that type Ⅰ and Ⅱ methanotrophs were widely present in natural wetlands in the United States and Japan. In 2012, the first study on methanotrophic diversity of wetland in the southern hemisphere was reported in Argentina. The high abundance of genusMethylocystissuggests that it is probably the major contributor to the methane oxidation in this Sphagnum wetland. Type Ⅰ and type Ⅱ methanotrophs were all detected and were present with different proportion in some natural wetlands of China. Great progress has already been made in the recent researches of the physiological and ecological characteristics of methanotrophs and their community diversity in the natural wetlands. With the arrival of the era of high-throughput sequencing and the development of new isolation and culture technology, the knowledge systems of methanotrophs will be refreshed more frequently.

methanotrophs; methane monooxygenase (MMO); methane; wetland

国家自然基金项目资助(11079053, 31200367)

2013-05-06;

2014-09-09

10.5846/stxb201305060936

*通讯作者Corresponding author.E-mail: cuixy@gucas.ac.cn

邓永翠, 车荣晓, 吴伊波, 王艳芬, 崔骁勇.好氧甲烷氧化菌生理生态特征及其在自然湿地中的群落多样性研究进展.生态学报,2015,35(14):4579-4591.

Deng Y C, Che R X, Wu Y B, Wang Y F, Cui X Y.A review of the physiological and ecological characteristics of methanotrophs and methanotrophic community diversity in the natural wetlands.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2015,35(14):4579-4591.