From Bilateralism to Multilateralism:Evolution and Prospects of ASEAN Defense Cooperation

2014-12-11

In 2010, the inaugural ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting Plus(ADMM-Plus) attracted the world’s attention, bringing awareness to ASEAN’s new role as a regional entity with increasing defense characteristics. The meeting marked a milestone in ASEAN’s multilateral efforts to enhance defense cooperation.1Refer to Ian Storey, “Good start on Asean defence cooperation”, The Straits Times (Singapore)October 16, 2010.Looking back at its historical development, bilateralism was the mainstream of ASEAN defense arrangements for a long period, and the gradual shift from bilateralism to multilateralism represents the most distinctive recent change in ASEAN defense cooperation.

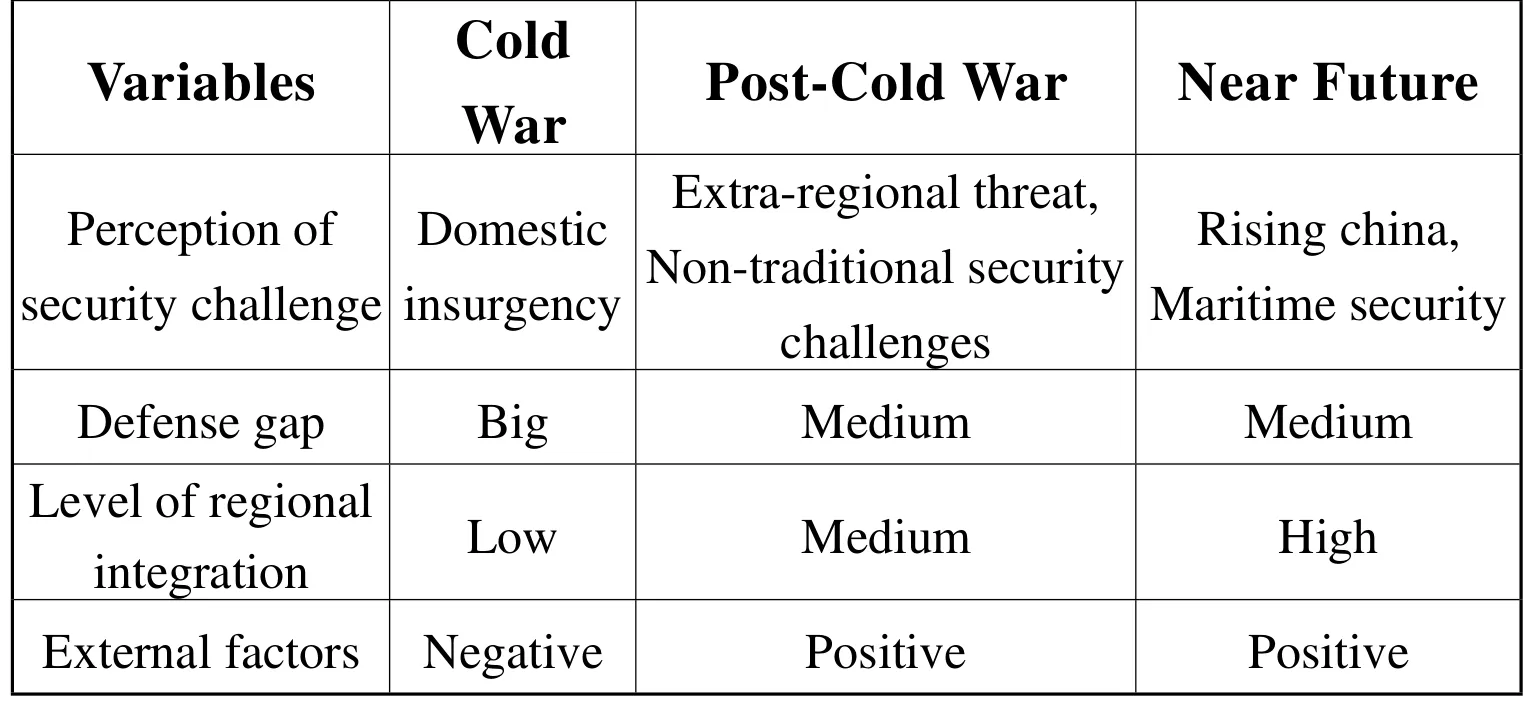

To undertake such an analysis, some basic concepts must first be defined. Security arrangements can generally be categorized as being bilateral or multilateral. Bilateralism prioritizes bilateral arrangements as the principal form for cooperation - for example, joint military training programs between Singapore and Indonesia fit into this category.2Andrew Yeo, “Bilateralism, Multilateralism, and Institutional Change in Northeast Asia’s Regional Security Architecture”, EAI Fellows Program Working Paper 30, April 2011, pp.1-8.Multilateralism is understood as a policy of seeking answers to security challenges in a multilateral rather than bilateral or unilateral manner.3Glenn D. H, “JAPAN AND THE ASEAN REGIONAL FORUM: BILATERALISM,MULTILATERALISM OR SUPPLEMENTALISM?”, p.161.Unlike multilateral military pacts such as the North-Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), ASEAN defense multilateralism does not necessarily refer to a military grouping.Instead, it refers more often to coordinated efforts for ASEAN-oriented regional security architecture. The following article will adopt a qualitative approach to analyze four key variables underlying the evolution of ASEAN defense cooperation in different periods and contexts: the perception of security challenges, defense gaps between member states, levels of regional integration and external factors. These variables will be applied as indicators in the analysis of the past, present and future.

ASEAN’s Defense Bilateralism in the Cold War Era

Since the inception of ASEAN in the 1960s, bilateralism has remained the fundamental choice of ASEAN states in terms of defense cooperation for certain reasons, even in spite of longstanding debates over the role and value of multilateralism.

Rejection of Defense Multilateralism

The 1st ASEAN Defense Ministers Plus Meeting in 2010 draws wide attention as it for the first time gathers defense chiefs from 10 Southeast Asian countries and eight dialogue partners.

Prior to the 1st ASEAN summit, Indonesia attempted to advance an approach of multilateralism, evidenced by its suggestion of a ‘joint council’ for defense cooperation and joint military exercises among ASEAN states.4Frank Frost, “The Origins and Evolution of ASEAN”, World Review 19(3), August 1980, p.10.After deliberations at the pre-summit meeting,however, the general consensus was that security considerations should not be institutionalized within ASEAN, and the 1st Bali Concord concluded with a refusal to change ASEAN from its status as a socio-economic organization.5Amitav Acharya, “A Survey of Military Cooperation Among the ASEAN States: Bilateralism or Alliance?”, Center for International and Strategic Studies, Occasional Paper No. 14, May 1990, p.6.In the aftermath of the Bali summit, ASEAN policy-makers continued to reject the idea of multilateral security and defense cooperation, typified by the Thai foreign minister’s declaration that ASEAN ‘had nothing to do with military cooperation.’6Ibid.

While rejecting the need for a military alliance, ASEAN member countries were quietly forging bilateral relationships to cope with various threats.7Ibid 5.Over the years, a network of informal bilateral defense network was developed, often being referred to as the ‘ASEAN defense spider web.’ Underpinning this network is a widespread conviction on the part of ASEAN leaders that bilateral cooperation is more advantageous than other forms of multilateral military cooperation.8Richard Sokolsky, Angel Rabasa, C.R. Neu, The Role of Southeast Asia in U.S. Strategy Toward China, (RAND, 2000), pp. 43-44.In the words of the former chief of the Malaysian armed forces: “Bilateral defense cooperation is flexible and provides wide-ranging options. The question of national independence and sovereignty is unaffected.”9Ibid, p. 44.

Major Forms of Bilateral Defense Cooperation

With the exception of Malaysia and the Philippines, all the other ASEAN states have developed some form of bilateral military links with one another,10Amitav, “A Survey of Military Cooperation Among the ASEAN States: Bilateralism or Alliance?”, p.1.mainly including:

(1) Border security arrangements

The initial motivation for defense cooperation within ASEAN came from the threat of communist insurgency.11Edited by Bates Gill and J.N. Mak, Arms, Transparency and Security in South-East Asia, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), p.50.Border security agreements were signed to contain the spillover effects of insurgent activities, and joint border committees and combined operations were initiated to control the trans-border movement of subversive elements. Some cooperation was later broadened to include illegal activities such as smuggling and drug trafficking.12Amitav, “A Survey of Military Cooperation Among the ASEAN States: Bilateralism or Alliance?”, pp.10-12.

(2) Intelligence sharing

Countries came to share intelligence with one another, covering both tactical matters and strategic issues including overall threat assessments. Furthermore, the intelligence branches of ASEAN member country armed forces exchanged intelligence both at a bilateral and multilateral level. Since the Bali summit, ASEAN countries have taken turns hosting annual meetings in this field.13Amitav, “A Survey of Military Cooperation Among the ASEAN States: Bilateralism or Alliance?”, pp.19-20.It is the only known form of multilateral defense cooperation among ASEAN states and set a precedent for multilateral meetings of ASEAN defense officials.14Ibid.

(3) Joint military exercise/training

Joint exercises witnessed an expansion both in the frequency and area covered - the number of exercises per year increased from 3 in 1972 to 15 in 1986, while the subjects expanded from counterinsurgency to conventional warfare.15Ibid, pp. 20-22ASEAN members also developed military ties through the provision of training facilities to others and mutual participation in each other’s officer training programs.16For example, Singapore was agreed to use training facilities in Brunei, Indonesia, Philippines,and Thailand. The Thai Air Force uses the Crow Valley range in the Philippines for air weapon testing purposes. Malaysia’s Jungle and Combat Warfare School has accepted trainees from other ASEAN states.

(4) Defense industry cooperation

ASEAN states have been more receptive to the idea of joint efforts in arms procurement, production and maintenance, considering it an ideal starting point for an ‘ASEAN Defense Community.’17Foreign Minister of Malaysia commented this. See Strait Times, May 6, 1989.In the late 1970s and early 1980s, some standardization of weapons systems occurred between ASEAN countries - F-5 and C-130 were acquired from the United States by all ASEAN states except Brunei,18Amitav, “A Survey of Military Cooperation Among the ASEAN States: Bilateralism or Alliance?”, p. 28.creating opportunities for a closer industrial cooperation.

Root Causes for Defense Bilateralism

There are several underlying causes for the defense bilateralism as follows.

(1) Perception of security challenges

There were two types and levels of challenges to ASEAN states during the Cold war: domestic insurgency and intra-regional conflict following the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia. At the internal level, ASEAN states adopted an ‘inward looking’ concept of security,based on the proposition that national security is dependent not on military alliances or the protection of any great power, but in selfreliance deriving from domestic factors.19David Irvine, ‘Making Haste Slowly: ASEAN from 1975’, in Alison Broinowski, Understanding ASEAN, London: Macmillan, 1982, p.40.

Driven by this concept, ASEAN emerged as a vehicle for economic cooperation (instead of a military entity) that could eliminate the sources of popular discontent. At the intra-regional level, ASEAN’s resistance to defense multilateralism was seriously challenged by the Vietnamese intrusion in 1978. Some ASEAN statesmen, including the former foreign minister of Indonesia who had previously opposed a military role for ASEAN, proposed that ASEAN should hold joint exercises on the Thai-Cambodian border.20Edited by Bates Gill and J.N. Mak, Arms, Transparency and Security in South-East Asia,pp.52-53.But this new move was subsequently rejected, partly due to differing perceptions of the situation in Vietnam.

(2) Defense gap among member states

Even though ASEAN has witnessed increasing familiarization through bilateral exercises and training, differences in language,military doctrine, overall military strategy and defense spending remain serious barriers impeding further cooperation. For example,Singapore’s emphasis on “forward defense” contrasts with Indonesia’s emphasis on “depth,” while Thailand’s preoccupation with land-based threats from the north conflicts with Malaysia’s increasing concerns over maritime security.21Amitav, “A Survey of Military Cooperation Among the ASEAN States: Bilateralism or Alliance?”, p.30.As a Philippines military official stated, “the armies of ASEAN do not have a set of standard doctrines necessary to conduct conventional war.”22Ibid. p. 26.As for defense industry cooperation,each ASEAN state has its own rules and decision-making processes that could hinder it.

(3) Level of regional integration

Upon the inception of ASEAN, multilateral mechanisms were still in their initial stage. The lack of mutual trust and the absence of knowledge and experience in multilateral cooperation was another important indigenous factor that constrained ASEAN defense ties.Some ASEAN statesmen, such as Lee Kuan Yew, took a gradualist view on this question. According to Lee, the initial objective of ASEAN should be mutual benefit in the field of economic cooperation, which could later spread into other areas, including security and defense.23Straits Times, November 19, 1975.

(4) External factors

Looking at Southeast Asia’s military weaknesses, no ASEAN country saw intra-ASEAN security cooperation as a substitute for their own strategic partnerships with external powers, evidenced by the continuing value placed on the United States military presence in the region.24Amitav, “A Survey of Military Cooperation Among the ASEAN States: Bilateralism or Alliance?”, pp. 35-36.For instance, confronted with the Vietnamese threat,Thailand sought assistance from the United States rather than rely on its ASEAN partners.25Ibid, p.8.TheFive Power Defense Arrangements, in addition, revealed ASEAN’s reliance on external powers.26Australia, Britain, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore signed the FPDA in 1971. The ASEAN countries also have a variety of defense arrangements with a number of EU countries. See Richard Sokolsky, The Role of Southeast Asia in U.S. Strategy Toward China, p.45.On the other hand, the United States at the time preferred bilateralism in East Asia, as opposed to its multilateral commitments in the West.The flexibility of bilateralism and the enhanced control of United States over its ‘rogue allies’ through bilateral arrangements made the option of strong multilateral institutions unlikely in Asia.27Andrew Yeo, “Bilateralism, Multilateralism, and Institutional Change in Northeast Asia’s Regional Security Architecture”, EAI Fellows Program Working Paper Series No. 30, April 2011,pp.4-5, http://www.eai.or.kr/data/bbs/eng_report/201104281643832.pdf.

Why Pursue Multilateralism in the post-Cold War Era?

Following the end of the Cold War, intra-ASEAN defense relations underwent a noticeable adjustment, and ASEAN leaders began to‘think the unthinkable’: a multilateral ASEAN security framework,as opposed to a military pact.28Amitav, “A Survey of Military Cooperation Among the ASEAN States: Bilateralism or Alliance?”, p.2.The Malaysian foreign minister went so far as to suggest an “ASEAN Defense Community,” while his Indonesian counterpart made a similar call for an ASEAN military arrangement in August 1989.29Ibid.The successive establishment of ARF,ADMM and other relevant multilateral mechanisms in recent years has further emboldened this trend, stemming from changes across four key variables:

(1) Perception of security challenges

ASEAN countries have generally perceived their security challenges in three different dimensions. First, they see growing external challenges. The withdrawal of United States troops from the Philippines left a security vacuum in Southeast Asia, alerting ASEAN states to the possibility that regional powers would step in to fill it up. The rise of China and remilitarization of Japan, in particular,provided external pressure on ASEAN to foster a collective security concept and strengthen multilateral coordination. Second, there has been an increase in intra-regional uncertainty. Territorial disputes between some ASEAN members that were concealed during the Cold War resurfaced in the 1990s, for example the controversies over BatuPuteh, LigitandenSipadan, as well as various fishing areas.30Lu Jianren, “Dong Meng Guo Jia De An Quan He Zuo Ji Ji Dian Kan Fa”, Zhan Lue Yu Guan Li, (Lu Jianren, “Security Cooperation of ASEAN states and observations”, Strategy and Management), http://blog.boxun.com/sixiang/991123/9911236.htm.This trend has been exacerbated by the arms races in Southeast Asia, pushing ASEAN policymakers to develop confidence-building measures and avoid multilateral conflict. Third, there has been a rise in transnational/nontraditional security threats. Nontraditional threats, such as piracy, terrorism and natural disaster often extend beyond the boundaries of individual states, requiring joint efforts from the armed forces of all regional countries.

(2) Defense gaps between member states

Operational and technical barriers, including the lack of standardization and differences in doctrines, are not insurmountable,even though they remain significant.31Amitav, “A Survey of Military Cooperation Among the ASEAN States: Bilateralism or Alliance?”, p.31.First, the doctrinal and language gap has been slowly bridged through bilateral cooperation,such as joint training exercises. Second, the capacity gap has been reduced by military build-up and modernization. In recent years,most ASEAN armed forces have shifted their focuses from antiinsurgency to conventional warfare, providing both conditions and motivations for broader and more pragmatic cooperation.

(3) Level of regional integration

According to a report conducted by the ASEAN Defense Senior Official Meeting (ADSOM) in 2008, the latest developments in ASEAN will help provide guidance to all ASEAN sectoral bodies,including the defense sector.32“Report of the ADSOM (25-26 Nov. 2008, Thailand) ” , December 20, 2009,http://admm.org.vn/sites/eng/Pages/reportoftheadsom(25-26november-nd-14494.html?cid=238.The second Bali Concord (2003),the ASEAN Charter, the ASEAN community Blueprint and other related documents set common goals and a norms-based framework for ASEAN defense cooperation.

(4) External factors

One of the most prominent trends since the end of the Cold War has been the rise of multilateralism worldwide, illustrated by intersecting multilateral mechanisms in Asia - EAS, APEC, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and more relevantly, WPNS and Shangri-La Dialogue.33EAS: East Asia Summit; APEC: Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation; WPNS: West Pacific Naval Symposium.This has fostered a regional climate conducive to ASEAN multilateral cooperation. Furthermore, the previous reluctance of the United States towards defense multilateralism has seen some changes. While still relying on bilateral alliances,the United States has started playing a much more positive role in advancing multilateral defense networks both in Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia.

Institutions for ASEAN Multilateral Cooperation

In light of the above-mentioned changing security context, ASEAN has promoted multilateral defense cooperation through gradual,institutionalized approaches.

ADMM-centered Institutionalization

The inauguration of ADMM in May 2006 marked a historic event in the evolution of ASEAN, establishing a new sectoral ministerial body and the highest defense mechanism within ASEAN. To guide the ADMM cooperation process, a 3-Year ADMM Work Program(2008-2010) was adopted in 2007, including activities in 5 areas.The 5th ADMM adopted a new 3-Year Program (2011-2013), which incorporated four areas: namely, strengthening regional defense and security cooperation; enhancing existing practical cooperation and developing possible cooperation; promoting enhanced ties with Dialogue Partners; and shaping and sharing of norms.34“ASEAN DEFENCE MINISTERS’ MEETING (ADMM) THREE-YEAR-WORK PROGRAM 2011-2013”, http://www.aseansec.org/19539.htm.With the adoption of two concept papers, cooperation on the issues of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief has been progressing significantly in the ADMM.35Two concept papers include: Concept Paper on the Use of ASEAN Military Assets and Capacities in Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) and the Concept Paper on Defense Establishments and Civil Society Organizations Cooperation on Non-Traditional Security.See “ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting (ADMM)”, http://www.aseansec.org/18816.htm.Exercises on HADR have also been conducted.

Another area is the ASEAN Chiefs of Defense Forces Informal Meeting (ACDFIM). Established in 2003, the ACDFIM is an annual mechanism for implementing decisions made by the ADMM. As a high-level military meeting, the ACDFIM is tasked with the role of serving as ‘the center of linkage and coordination of military cooperative activities’ in the region.36“Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defense Ministers on Strengthening Defense Cooperation of ASEAN in the Global Community to Face New Challenges”, 19 May 2011, http://www.aseansec.org/26304.htm.

Lastly, there is also the ASEAN Military Intelligence Informal Meeting (AMIIM) and the ASEAN Military Operations Information Meeting (AMOIM). The two meetings are also held annually and are accountable to the ACDFIM. The AMOIM was inaugurated in 2011 to enhance practical cooperation among defense forces. The latest AMIIM pointed out that ASEAN military intelligence cooperation should be prioritized in order to help enhance and build regional community.37“ASEAN military intelligence meeting opens”, 27 Mar. 2012, http://en.vietnamplus.vn/Home/ASEAN-military-intelligence-meeting-opens/20123/25150.vnplusIn addition, there are meetings of Service Chiefs and exchanges of officers and soldiers, which are held annually.38Speech by Chief of General Staff of Vietnam People’s Army At 7th ASEAN Chiefs of Defense Forces Informal Meeting (ACDFIM-7), March 25, 2010,http://admm.org.vn/sites/eng/Pages/speechbychiefofgeneralstaff-nd-14549.html?cid=230.

ASEAN-centered Regional Networking

The ADMM-Plus, which brings together defense ministers from ten ASEAN members and eight major regional powers, has laid a strong foundation for the ADMM to cooperate with Dialogue Partners from the “Plus countries” to address common security challenges. It reaffirms ASEAN’s central role in bringing all major players in the Asia-Pacific together to help construct strong security architecture.39Ian Storey, “Good start on Asean defence cooperation”, The Straits Times (Singapore),October16, 2010.Held every three years, its main work is undertaken by expert working groups (ADSOM+WG) in five priority areas.40HADR field hosted by Vietnam and China, maritime security sector by Malaysia and Australia,anti-terrorism by Indonesia and the U.S, military medicine by Singapore and Japan, peacekeeping operations by the Philippines and New Zealand. See “Ready for ADSOM+WG”, December 7,2010, http://admm.org.vn/sites/eng/Pages/readyforadsom+wg-nd-14762.html?cid=238.Another ASEAN-centered platform, ARF, has also made concrete achievements, increasing transparency promoted through the exchange of defense information and publication of defense white papers; and networking between defense and military officials of ARF participants.41See ASEAN Regional Forum website, http://aseanregionalforum.asean.org/about.html.ASEAN also conducts regular negotiations with other ARF members under the framework of the “ARF Security Policy Conference,” an annual vice defense minister-level meeting initiated by China in 2004.

CBM-centered Gradualism

The so-called “ASEAN way” is applied and embodied in defense cooperation. The 2011 ADMM reaffirmed ASEAN’s consensusbased decision-making process in the ADMM. Although it now has more scheduled meetings, the process of defense multilateralism is still informal and does not have a clearly defined structure and set of rules. For example, the 3-Year ADMM Work Program stipulates so-called ‘desired outcomes’ rather than clear criteria or concrete measures.42Refer to ASEAN website, http://www.aseansec.org/19539.htm.Following this informal methodology that deliberately avoids sensitivity, ASEAN defense relations have witnessed an adjustment from anti-subversion cooperation to transparencyoriented cooperation since 1980s. The intra-ASEAN military cooperation and the extra-ASEAN engagement largely focus on confidence-building measures, the main function of which is to reduce the likelihood of military conflict and facilitate crisis management,as opposed to threat-oriented cooperation.43Edited by Bates Gill and J.N. Mak, Arms, Transparency and Security in South-East Asia,pp.58-60.

Future Outlook and Implications

The ASEAN Political-Security Community (APSC) Blueprint,adopted at the 14th ASEAN Summit in 2009, envisions a roadmap and timetable for establishing the APSC by 2015.44See the ASEAN website, http://www.aseansec.org/18741.htm.Four variables must be examined in the near future in order to examine how far the ASEAN defense cooperation can go in building a security community.

First, given the fast development of China and the escalation of territorial disputes in the South China Sea, there is an increasing convergence on the assessment of security challenges faced by ASEAN states, evidenced by the growing role of ASEAN as a bloc in the resolution of South China Sea disputes. Driven by the objective of avoiding dominance by any individual superpower, the ASEAN armed forces will be in a better position to facilitate traditionalsecurity cooperation. Problems in the maritime sphere could prove to serve as an impetus for the ASEAN security framework of the future.45Amitav, “A Survey of Military Cooperation Among the ASEAN States: Bilateralism or Alliance?”, p.36.

Second, the defense gap between member states is unlikely to witness big changes in the short-term. This is also dependent on the implementation of existing agreements and documents, like the Concept Paper on the Establishment of ASEAN Defense Industry Collaboration (ADIC), adopted at the 5th ADMM.

Third, ASEAN community development in other areas will have an impact on this issue, as successful economic and social integration will foster a precious ASEAN-priority awareness among ASEAN leaders and the public. ASEAN defense cooperation could then garner wider social acceptance and higher public expectations.

Lastly, the involvement of great powers in the region, especially the United States’ multilateral defense outreach in Southeast Asia,will provide ASEAN with new platforms for multilateral cooperation,while stimulating intra-ASEAN coordination and integration if states want to prevent external dominance.

Overview of the Qualitative Analysis

Several trends for ASEAN defense cooperation in the foreseeable future are worth discussing based on the above analysis.

Multilateralism vs Bilateralism: Institutional Layering

As some analysts contend, shifts in the security environment will unveil opportunities for greater multilateral cooperation, in conjunction with current bilateral alliances through a process of institutional layering.46Andrew Yeo, “Bilateralism, Multilateralism, and Institutional Change in Northeast Asia’s Regional Security Architecture”, p. 2.On the one hand, multilateralism will adopt a bigger role, while existing bilateral systems will not be reduced.

On the other hand, multilateralism and bilateralism will be reciprocal, as the mutual trust facilitated by multilateral cooperation will enhance bilateral ties, and the intensified bilateral cooperation may inject experience and greater capacity into multilateral relationships. There will also be a two-tiered multilateralism in the region: the intra-ASEAN defense cooptation and the extra-ASEAN multilateral engagement with strategic stakeholders.

Transparency-oriented vs Threat-oriented: Multiple Objectives

ASEAN defense cooperation is expected to expand gradually,incorporating three main components. The first includes existing transparency-oriented activities, while the second encompasses emerging capacity-oriented cooperation. The ASEAN Chiefs of Defense Forces Informal Meeting in 2012 discussed assessments on promoting joint military operations toward the creation of an ASEAN Community in 2015.47“ASEAN defense chiefs meet in Cambodia”, March 29, 2012,http://en.vietnamplus.vn/Home/ASEAN-defence-chiefs-meet-in-Cambodia/20123/25199.vnplus.A kind of ASEAN Military Capacity based on joint planning, training and operations may come into being in the near future. In fact, the ADMM 3-Year-Work Program(2011-2013) has already put the ‘identification of ASEAN Military capacity of the peacekeeping force’ into its agenda, including the objective of networking between ASEAN peacekeeping centers to conduct joint planning, training and sharing of experiences. The 2010 ACDFIM also called for ‘a highly-synchronized coordination and collaboration among forces’ by creating a strong link and coordination in information sharing as well as joint activities.48Speech by Chief of General Staff of Vietnam People’s Army At 7th ASEAN Chiefs of Defense Forces Informal Meeting (ACDFIM-7), March 25, 2010,http://admm.org.vn/sites/eng/Pages/speechbychiefofgeneralstaff-nd-14549.html?cid=230.Practical defense cooperation will increase in addition to confidencebuilding measures.

Third, there will be an increase in leverage-oriented cooperation.Defense multilateralism can be viewed as a platform for increasing ASEAN’s influence and bargaining power in regional security issues,either by showing ASEAN’s collective will or its close ties with certain regional powers. One example is the goal set in the ADMM 3-Year-Work Program that the ASEAN defense body should advance the full implementation of the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea and support the adoption of a regional code of conduct in the South China Sea.49“ASEAN DEFENCE MINISTERS’ MEETING (ADMM) THREE-YEAR-WORK PROGRAM 2011-2013”, http://www.aseansec.org/19539.htm.

Traditional vs Non-Traditional: Prioritized Areas

Non-traditional security will remain the priority for cooperative activities. The 7th ASEAN Chiefs of Defense Forces Informal Meeting points out that “while continuing with dialogues, confidence building and experience sharing measures, it is necessary to forge ahead with specific activities of cooperation, most tangibly those of search and rescue as well as HADR; cooperative activities in such areas will provide a new thrust for ASEAN military cooperation.”

Under the flag of non-traditional security cooperation, there has also been an increase in the use of conventional warfare units. Namely,non-traditional security cooperation has numerous effects: practicing capabilities responding to disaster relief and illegal activities, and preparing for conventional armed conflicts.

In summary, ASEAN defense cooperation will witness further developments despite certain limitations.

First, it will still retain its defensive nature. The main purposes for ASEAN defense cooperation will continue to be confidence-building and crisis-prevention, instead of becoming a traditional military bloc.

Second, it will be a gradual process. ASEAN defense establishments,while searching for a single voice, will undertake diverse actions with diverging priorities. Non-traditional security cooperation will remain a key area.

Lastly, it will be advanced in an open manner. Multilateralism also encompasses openness and more engagement with other regional powers.

Some analysts argue that ASEAN will gain more bargaining power over China on maritime issues, which may introduce complexity into bilateral relations and regional stability. It should be noted, however, that even with closer defense ties, ASEAN still does not have the willingness and capacity to confront China. On the contrary, multilateral defense communications can promote mutual trust and help foster the habit of cooperation among militaries. With more pragmatic cooperation, such as joint exercises and sharing of military assets, ASEAN and other regional countries will be in a better position to combat complex security challenges.

More importantly, this cooperation will strengthen ‘ASEAN Centrality’ by enhancing ASEAN awareness and capacity, which helps ASEAN play a bigger role in regional security cooperation,and will inject new vitality into current multilateral mechanisms such as the ADMM-Plus and ARF. In a word, the enhanced defense networking among ASEAN states will help facilitate, not destabilize,regional peace and multi-polarity.

China always welcomes and supports ‘ASEAN Centrality’ in regional cooperation. In addition to bilateral exchanges, more attention must be paid to multilateral defense cooperation with ASEAN in future.As Chinese defense minister Chang Wanquan stated: “China is ready to take concerted efforts with all ASEAN parties to actively utilize the existing security mechanisms, strengthen communication and synergy and jointly promote the building of new regional security cooperation architecture with Asian characteristics.”50“Chinese defense minister calls for practical cooperation in boosting ties with ASEAN”, May 8, 2013, http://www.taiwan.cn/english/News/dn/201305/t20130508_4178642.htm.

杂志排行

China International Studies的其它文章

- TTIP: The Economic and Strategic Effects

- Prospecting and Developing South China Sea Oil and Gas Resources

- US-Vietnam Security Cooperation:Development and Prospects

- The Trends of Cross-Straits Relations in a Changing East Asia

- Laying the Foundations of Peace and Stability for an Asian Community of Shared Destiny

- China’s African Engagement:Advancing Multilateralism