Visual Memories of 1911

2014-11-24

It is not without trepidation that I approach the assignment of chronicling a history of the 1911 Revolution with photographs. This year, 2011, marks the centennial of the uprising in Wuchang, Hubei Province, which brought down the great Qing Dynasty and, with it, established what would become Asias first republic. But while the uprising removed the Manchu rulers, the early years of the Republic of China remained a melting pot of foreign nationals, a situation that continued for years to come.

For this reason, as I embarked on my research, so began a journey that would take me not only across the mainland of China and Taiwan, but across Europe and America too, to public and private collections spread across different continents. From Tokyo to Sydney, London to Paris, Los Angeles to New York, I viewed a wealth of original photographs which have been carefully preserved for more than a century.

On the eve of the centennial of the Wuchang Uprising, which took place in Wuhan, the provincial seat of Hubei, on October 10, 1911, this collection of photographs frames the visual context of the“humiliation and imperialism” that was then identified as the impetus driving the uprising. The images further reveal how the uprising accelerated the collapse of the Qing. Without present-day context of Chinas peaceful rise and the fact that it has now replaced Japan as the worlds second largest economy, generations of Chinese people who endured a profound sense of victimhood throughout the 20th Century might regard these images merely as “old photographs.” Now, however, it is possible to see that they are much more than “old photos.” Brought together as an exhibition and in this accompanying book, the collection represents visual documentation of social lives and events that have occupied a significant place in the hearts and minds of Chinese intellectuals since the May Fourth Movement.

The collection includes images from the late 19th Century showing the Second Opium War, the atmosphere inside the imperial court, and the lives of the mighty as well as the poor. They show scenes from the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895, the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, and the Russo-Japanese War fought on Chinese soil from 1904 to 1905. In the decade immediately following the uprising in 1911 we find images of Yuan Shikai, who failed in his attempt to anoint himself the last emperor, after which China descended into a decade known as the Warlord Era.

To examine these issues in a broader contemporary context, I invited three prominent scholars, Joseph Esherick, Zhang Haipeng and Max K. W. Huang, to share their distinctive perspectives on the 1911 Revolution. By charting its course, their words help us reflect on the event itself, its failures and achievements, and what it means to Chinese people today, one hundred years later.

Photography was invented by a Frenchman, Louis Daguerre, in 1839. In the new world brought by the age of European Enlightenment and following the Industrial Revolution, Western Europeans began more earnestly seeking territories overseas to establish new markets and procure raw materials and cheap labor, so photography evolved in its social documentation role both at home and abroad. In tandem with the writing of historians, it was used to serve each of these goals. Photography occupied a surprisingly prominent role in the activities of late 19th-Century foreign missionaries as they went out into the world to proselytize Christianity. Those who chose China as their destination would become responsible for a rich photographic archive of this period of Chinese history.

Photographic representation of China and the Chinese people of the period from 1860 to the end of the First World War accounts for a large part of European and American interpretations of China to Western audiences. As such, this body of photographic works remains an extraordinarily rich record of history, and one which is essential for the creation of a meaningful picture of that period for audiences today.

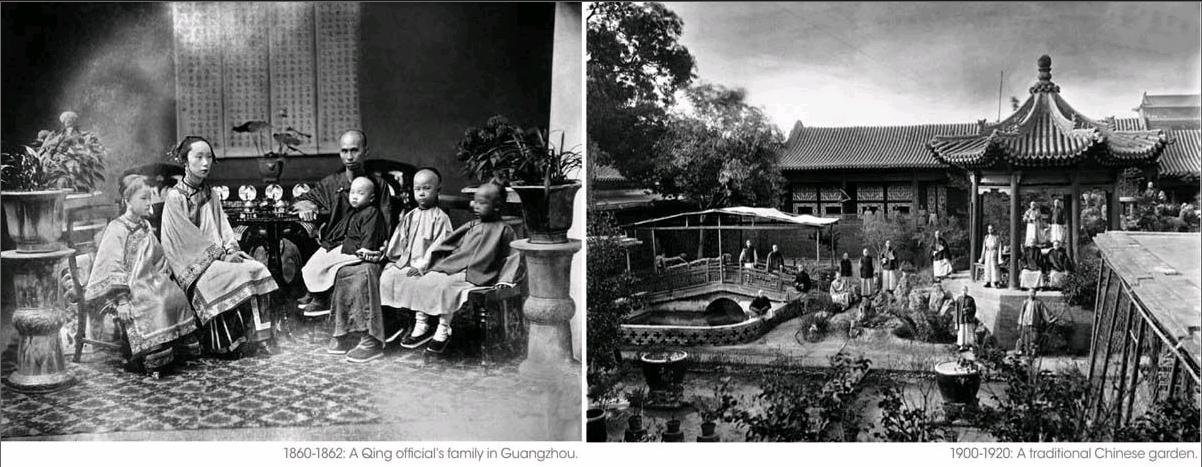

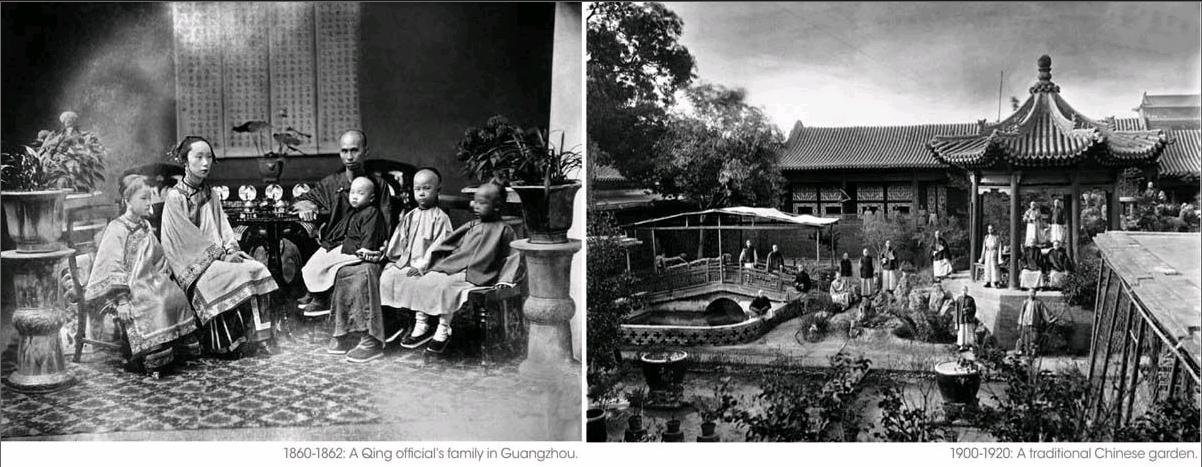

Looking back at existent images from the period of the 19th and early 20th centuries lead- ing up to 1911, these photographs have distinctive commonality. They were taken, by and large, by people who were employed in professions related to diplomacy, business, arms dealing, adventuring and traveling. Only a handful were snapped by a brand new type of professional: the photographer. China and its people were portrayed alternately as exotic, crude – or heroic, if you asked them.

In the post-modern world, Western art historians have been critical of the photographic portraiture of the Chinese taken by visiting photographers or by Chinese studio photographers who emulated the styles of their Western counterparts between 1860 and 1905. Following the two Opium Wars (1840-1842 and 1856-1860), both the Boxer Rebellion in 1900 and the Chinese Exclusion Act passed by U.S. Congress in May 1882 were critical factors contributing to negative accounts and, at times, racist representations of“Chinese subjects” in photographs.

Most photographs in this arena were taken around and focused on life in the treaty ports(Guangzhou, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Shanghai and Qingdao), and in European and American settlements as well as Japanese military quarters. Many photographic archives in European libraries and other collections grouped photographs of China together with other countries such as Siam(Thailand), Indonesia, India and Japan.

Readers will find examples of these stylized photographs here. By selecting and including these images, we hope that this collection can better illustrate how Chinese subjects were portrayed by Western photographers.

Through the photographs compiled here, this book lays out visual context and backdrop for the historic events around 1911 by describing the daily lives, social events, customs and traditions, as well as upheavals of political turmoil in the period surrounding Chinas first republic. Importantly, together they provide a visual experience of those times for audiences today, as well as an opportunity to reflect on how as a people the Chinese were portrayed abroad a hundred years ago, long before China could conceive of joining the World Trade Organization (WTO), which finally happened in 2001.

To describe these photographs as conforming to a biased view which saw Chinese people as“exotic” above all else is too simplistic. They sear the collective memory of the history of the Chinese people, lending insight into what previous generations described in literature and communal parlance of the “Hundred Years of Humiliation.”

Many books reference this subject, a number of which I have cited as sources, but this is the first such attempt to create a comprehensive visual narrative.

By presenting the visual history leading up to and immediately following 1911, we hope that both words and pictures can find their place in our schools and universities. Richard Kagan, an American analyst of foreign affairs who is known to be critical of “orientalism,” recently penned an article titled Multiple Chinas, Multiple Americas, in which he wrote:

“As teachers, we daily face the problem of inappropriate comparisons, stereotyped descriptions, hyperbolic fears, and selective sculpting of facts and generalization. The paradigm of the‘discovery of China in the 1970s still controls our perceptions. The division is between those who still see China as a positive personal experience in terms of visiting it and helping it develop, and those who see it as a threat. As teachers and citizens, it is necessary to pull back from the extremes of blind loathing or admiration.”[Hong Kong Economic Journal (“My First Trip to China” Series, www.hkej.com), January 29, 2011.]

It is with this in mind that I hope this collection of photographs can lend a nuanced visual appendix to views put forth by historians of modern Chinese history.

The Tumultuous Road to 1911: A Visual History

By Liu Heung Shing, Hinabook of World Publishing

Corporation, July 2014

The Tumultuous Road to 1911: A Visual History chronicles the history surrounding “1911” – a radical crossroads between the Second Opium War (1856) and warlord fighting – with plentiful original photographs from across the world, one third of which are being published for the first time in hopes of helping readers and historians better understand and review history, the 1911 Revolution in particular, more objectively.

It took the author over a year to collect the old photos from public libraries and museums as well as personal collections around the world.

In his latest book, On China, former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger observed that as China seeks to interact with the world, many of Chinas contemporary liberal internationalists still believe that the West has gravely wronged China – injuries from which China is only now recovering.

“It is with this in mind that I hope this collection of photographs can lend a nuanced visual appendix to the views put forth by historians of modern Chinese history,”remarks the author. All the photos taken by photographers, missionaries and adventurers from other parts of the world reflect the historical events navigating the progress of modern China.

Peter Hessler, author of Country Driving: A Journey Through China from Farm to Factory, opined that this extraordinary photo album reflects the fierce conflict between China and the West, which lasted for over a century. Tirelessly hunting throughout the world, Liu dug deep for imagery of figures of the times, including officials, students, and even ear-cleaners, who were all thrown into the eye of the storm. His book depicts Chinese society a century ago from a unique perspective with visual images, and that era is still influential to China today.

Ron Javers, former editor-in-chief of Newsweek international edition, commented that each photo collected in the book captures glimpses of tension, joy, sadness, and the humiliation of the era and is bestowed with the vitality of pure, unadorned dignity.

A graduate of Hunter College, part of the City University of New York, now living in Beijing, Liu Heung Shing was a Pulitzer-winning correspondent and photojournalist for the Associated Press offices in Beijing, Los Angeles, New Delhi, Seoul, and Moscow. He took a massive number of photos covering subjects ranging from the Democracy Wall at Xidan, Beijing and Chinas economic reform during the 1980s to the religious conflicts in Sri Lanka, the Soviet Union dispatching troops to Afghanistan, and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

He is known for his widely acclaimed books, including China After Mao, China, Portrait of a Country, and Shanghai: A History in Photographs, 1842-Today, in collaboration with Karen Rose Smith in 2010.