Faces of the War

2014-10-29BystaffreporterLU

By+staff+reporter+LU+RUCAI

John H. D. Rabe

The German businessman was working at the Siemens AG China Corporations Nanjing (Nanking) office when Japanese armies seized the Chinese capital on December 13, 1937. He witnessed the brutal massacre of over 300,000 Chinese civilians in the following six weeks, and recorded it in his diary.

On December 14, 1937 he wrote: “It is not until we tour the city that we learn the extent of destruction. We come across corpses every 100 to 200 yards. The bodies of civilians that I examined had bullet holes in their backs. These people had been presumably fl eeing and were shot from behind. The Japanese march through the city in groups of 10 to 20 soldiers and loot the shops ... I watched with my own eyes as they looted the café of our German baker Herr Kiessling. Hempels hotel was broken into as well, as was almost every shop on Chung Shan and Taiping Road.”

To save lives from the carnage, a group of foreign nationals founded the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone, and Rabe was elected chair. The committee set up 25 shelters in the city that accommodated over 200,000 refugees. Rabe opened his home to war victims, and brought in more than 600 of them. Members of the international committee worked in shifts day and night at the headquarters,guarding the shelters, fielding refugeescomplaints and providing them with food and water. Meanwhile they documented the atrocities of the Japanese occupiers.

Rabes wartime dairy (The Good German of Nanking in the U.K. and The Good Man of Nanking in the U.S.) was later published. It contains a raft of documents and correspondence from the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone, which are all marked “5 Ninghai Road,” address of the committees headquarters. The compound was formerly the German embassy in Nanjing. A black and white photo from 1937 shows Chinese refugees in thick winter clothes squatting or sitting in the yard, waiting for food. To protect the location from air strikes, a safety zone flag (red cross in a red circle) was unfurled across the lawn.

During his March visit to Germany Chinese President Xi Jinping mentioned Rabe, saying he is “widely respected and loved in China.” On the site of Rabes former residence in Nanjing –at 1 Xiaofenqiao, Gulou District, on the campus of Nanjing University – there is a memorial hall of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone and a research center for international peace and conflicts dissolution. Last year the municipal government of Nanjing funded the construction of Rabes tomb in Berlin. As President Xi said in his speech, “In China we cherish the memory of Mr. Rabe as a man who demonstrated great compassion for life and love of peace.”

Jean Augustin Bussiere

At the 50th anniversary commemorations of the establishment of SinoFrench diplomatic relations in Paris on March 27, Chinese President Xi Jinping said, “We will never forget the contributions made by numerous French friends to the cause of Chinas development. One of them is Jean Augustin Bussiere, a French doctor who risked his life to transport much needed medicine by bike to an anti-Japanese base in China.”

Bussiere first came to China in 1912, and returned to France in 1954. During his 40-plus-year stay in China, he worked at the French embassy and later at the French and German hospitals located in Beijings Legation Street(now Dongjiaominxiang). Meanwhile, Bussiere was also active in other fields: He co-founded the Sino-French University and, together with eminent educators Cai Yuanpei and Li Shizeng, advanced the campaign for Chinese students to study in France on a workstudy basis.

In the Western Hills area of Beijings Haidian District is a cluster of historical sites recording Sino-French cultural exchanges. Last year, the Haidian district government initiated a renovation project on these buildings, among which is Dr. Bussieres former residence, the Villa of Bussiere.

Bussiere owned two dwellings in Beijing. People from neighboring communities could see the doctor for free. This was a great boon for impoverished, ordinary Chinese back then, especially farmers.

Bussiere sympathized with Chinese peoples suffering during the Japanese aggression against China. Miaofeng Mountain where the Villa of Bussiere nestled was one of the strongholds of the anti-Japanese guerilla forces led by the Communist Party of China. Dr. Bussiere not only regularly treated wounded Chinese soldiers, but also agreed to make his villa a communication station for the CPC in Beijing. Around 1939, Nie Rongzhen, a CPC commander, led his troop to establish an anti-Japanese base in neighboring Hebei Province, where medicines were urgently needed for wounded soldiers. Learning the news, Dr. Bussiere, then in his 60s, risked his life to transfer medicines and medical apparatus from the downtown area to his suburban villa by bike. There he passed them on to the guerrilla forces, so making significant contributions to Chinas anti-Japanese campaign.

On March 30, a ceremony was held to launch the filming of The Villa of Bussiere, a documentary on Dr. Bussieres life. Its aims is to encourage Chinese people to learn more about the French doctor and his relationship with China.

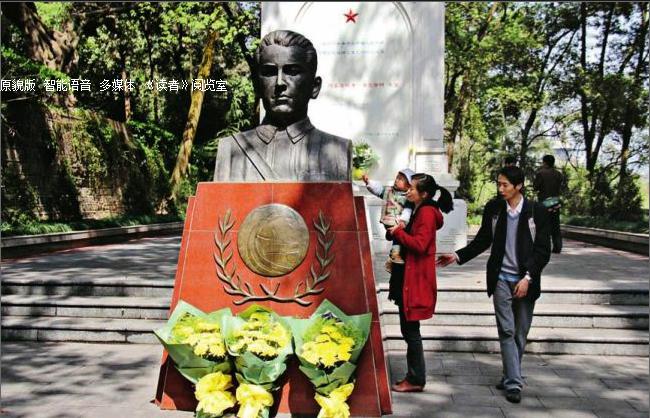

Grigori Akimovich Kulishenko

Building of the tomb of Grigori Akimovich Kulishenko in Xishan Park in Wanzhou, Chongqing, was completed in 1958. That year, the Red Cross Society of China, on behalf of the Chinese government, invited Kulishenkos widow and daughter to China to attend a sacrificial ceremony at the tomb during the October 1 National Day holiday. Later, at the National Day reception in Beijing, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai told them, “The Chinese people will always remember Grigori Kulishenko.”

From the end of 1937 to 1939, the Soviet Union sent more than 2,000 air force personnel to give battle in China, 700 of whom took part in aerial campaigns in defense of Nanjing, Wuhan and Chongqing. More than 200 of these airmen sacrificed their lives for China. Kulishenko was one of the two highest ranking Soviet air force officers.

Born in Ukraine, Kulishenko had been commander of a Soviet Union fighter squadron. In May 1939, he led a volunteer squadron of long-range bombers to help China fight Japanese invaders. They landed and were stationed at Chengdu Shuangliu Taipingsi Airport.

In addition to battle missions, these Soviet airmen were also responsible for training Chinese aviation personnel. Kulishenko personally conducted stringent flight instruction programs to perfect Chinese pilots flying skills. By the summer of 1939, he and his fellow Soviet Union instructors had trained more than 1,000 Chinese pilots, 80 navigators and 8,000 aviation technicians.

On October 14, 1939, Kulishenko led his squadron in a life-and-death struggle against Japanese fighter planes over Wuhan. His bomber shot down six Japanese planes. Kulinshenkos aircraft, however, was hit and he was forced to return to the base. His plane lost balance as it flew over Wanzhou, now a district of Chongqing. To ensure the safety of people on the ground, Kulishenko executed a landing on the Yangtze River. Others of the aircrew were able to scramble out, but Kulishenko could not escape from the cabin before it flooded. His body was found 20 days later. He was buried at the foot of a hill in Wanzhou.

Word of Kulishenkos heroic deeds soon spread throughout the country. As the volunteers location in China was classified information, Kulishenkos family in the Soviet Union did not receive the tragic news that he had been killed in action until several months later. Even then, they were not told about the manner or place of his death.

The Chinese people have never forgotten Kulishenko. Since the 1970s, the Ministry of Civil Affairs has allocated funds on four occasions specifically to renovate his tomb. It was designated in 2009 as site of a Memorial for Martyrs under National Protection. In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping delivered a speech at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations. He made special mention of the Chinese mother and son, Tan Zhonghui and Wei Yingxiang, who have tended Kulishenkos tomb for more than 50 years, so attesting to the friendship between China and Russia.

“I heard Kulishenkos story from my mother. I have told it to my son and will in turn tell it to my grandson. I think of it as a legacy,” Wei Yingxiang said. After hearing about this mother-and-son team through President Xis speech, Kulishenkos grandson personally called Wei Yingxiang. “His gratitude is my best possible commendation,” Wei said.

He Fengshan

Israel posthumously honored He Fengshan (Fengshan Ho) with the title Righteous among the Nations in January, 2001 at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem. His daughter He Manli said of He Fengshan: “My father was a typical Chinese, generous and broad-minded. He believed that compassion and wanting to help is natural. When driven by humanitarian concerns, this is the way it should be.”

He Fengshan gained a PhD in political economics from the University of Munich in 1932, and in 1935 embarked on his diplomatic career. In May 1938, he was assigned to the post of Chinese consul-general in Vienna.

His appointment coincided with the reign of terror of the newly installed Nazi regime in Austria, under which the 185,000 Jews living there suffered inhuman persecution. Their survival depended on fleeing Austria, but the Nazi authorities demanded that Jews traveling to another country must first obtain an entry visa and boat ticket. He maintained close personal relationships with certain Jewish people. Their plight drove him to help them escape, and to issue Chinese visas to all Jewish applicants. From May to October 1939, He issued 1,900 visas to China.

Shanghai was at that time an “open city” that did not require a visa, but Jews nonetheless needed one to leave Austria.“Although aware that Shanghai was not the eventual destination of some applicants, my father knew that unless they obtained a visa they would be sent to concentration camps,” He Manli said.

In early 1939, the Nazis confiscated the Chinese Consulate in Vienna, claiming that it was Jewish property. To reopen the office, He Fengshan had to rent a small house at his own expense. At this time he also met with criticism from Chinese political circles, some of whom accused him of selling visas to Jews for profit. Although proven innocent, he was removed from his post in Vienna in May 1940.

In his memoir My Forty Years as a Diplomat, published in 1990, He wrote about his experiences during this period. He describes how, after Austrias Anschluss or union with Germany, the plight of Jews worsened as their persecution intensified. Hes account tells of his maintaining close contact with U.S. religious and charitable organizations that helped to save Jewish people, and how he meanwhile did all he could to help and save them.

He returned to China when the country was embroiled in the War of Resistance against Japan. After retirement in 1973, he settled in San Francisco. During his lifetime, He seldom spoke about his deeds. They became public only after his death in 1997. The obituary his daughter Manli wrote for the Boston Globe included mention of her father issuing visas to Jews. American historian Eric Saul immediately contacted Manli, asking her to elaborate. Saul later searched out Jews who had survived due to the visas He had issued, and also some of their descendants.

He Fengshans heroic actions were enshrined at the entrance to the Visas for Life exhibition in Stockholm in January 2000. He is regarded as “Chinas Schindler.”

Nie Rongzhen and Kato Mihoko

In 1999, to mark the centenary of renowned Chinese Marshal Nie Rongzhens birth, Jiangjin City (now a district of Chongqing), Nies hometown, and Kato Mihokos hometown, Miyakonojōin Japan, became sister cities. Mihoko said her fathers wish had finally been fulfilled. Her “father” was the eminent Marshal Nie.

On May 28, 1980, Chinas national news agency Xinhua published a report titled “Little Japanese Girl, Where Are You?” The story was then reprinted in many domestic newspapers including Peoples Daily and PLA Daily. The story tells how soldiers of the Eighth Route Army rescued a Japanese orphan from gunfire during the Great Campaign with One Hundred Regiments (hereafter, Hundred Regiments Campaign) in 1940. Several days after its publication, Japans Yomiuri Shimbun traced the little girl of the story to Miyakonojō, Miyazaki. Her name was Kato Mihoko, mother of three girls.

Mihokos story started in August, 1940 in a village along the railway line from Shijiazhuang in Hebei Province to Taiyuan in Shanxi Province. It was a vital transportation line crossing the Jingxing Coal Mine, the Japanese armys fuel base in North China. Mihokos father worked at the railway station of the coal mine and was responsible for coal transportation.

The Hundred Regiments Campaign was the largest and longest CPC-led anti-Japanese battle in North China, launched on August 20, 1940. While attacking the Japanese armys base in the Jingxing mine, Chinese soldiers risked their lives to rescue two girls, one aged four, the other barely one year old, from the flames of war. The two girls were Mihoko and her younger sister. Their parents were both killed in a bombing raid.

Clueless about how to deal with the two little girls, the Chinese soldiers reported to headquarters. Commander Nie Rongzhen sent for the two sisters. Soon, the older girl, Mihoko, formed a bond with Nie, following him wherever he went and often clinging to his trouser legs. A war correspondent captured a group photo of Nie and the little girl outside the command post. This photo became a valuable testimony to the historical moment.

Since Japanese bombings were still rampant around the CPC front command post, for safetys sake Nie decided to send the two girls back to the Japanese army camp. Nie wrote a letter in person to the Japanese chief commander in Shijiazhuang and entrusted a reliable local farmer to take the girls there. The farmer hoisted the two girls up in baskets on a pole and carried them. Worrying that the girls might act up, Nie filled the baskets with fruit to appease the little travelers. According to Nie Rongzhens biography, after receiving the two girls, the Japanese army wrote a letter to Nie expressing their gratitude.

On their arrival at the Japanese base, the two girls were sent to a local hospital. Sadly, due to a severe wound, the younger one died. In October 1940, the older girl, Mihoko, was brought back to Japan by her uncle and went to live with her grandmother. When recalling her experience in China she told her family of sitting in a basket eating pears. These details later formed an important basis for verifying her identity.

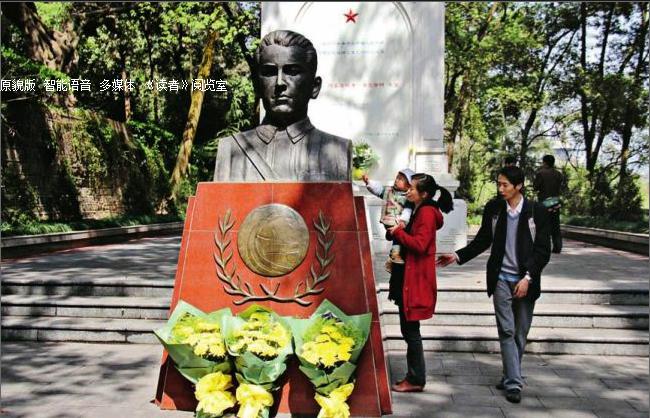

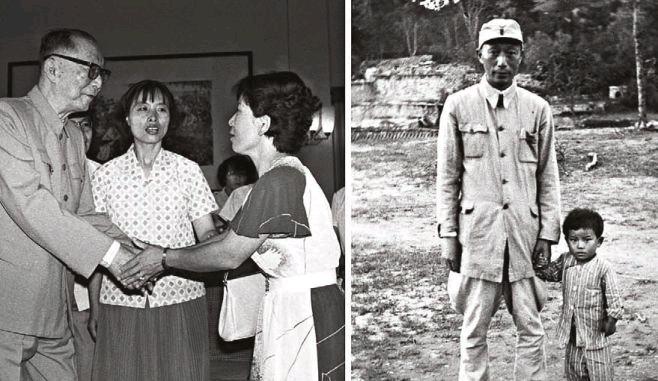

On learning of the Xinhua report, Mihoko wrote to Marshal Nie, expressing her thanks to him for saving her life and also indicating her wish to revisit China. Then, on July 10, 1980, at the invitation of the China-Japan Friendship Association, Mihoko began her visit to China. On July 14, Nie received Mihoko and her family at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. A documentary recording Mihokos visit was made by Chinas Central Studio of New Reels Production.

“It had never occurred to me that we would be so warmly received in China. Im just an ordinary Japanese woman. My miraculous childhood experience has attracted so much love and attention, since our two peoples cherish a common wish: lasting peace and friendship between our two countries,” Mihoko told media while visiting China.

Back in Japan, Mihoko is devoted to promoting exchanges and friendship between China and Japan. Marshal Nies daughter, Nie Li, and granddaughter, Nie Fei, have continued the family bond in their correspondence with Mihoko. They hope the two countries friendship will be passed on from generation to generation.