Uncomfortable Truths

2014-10-23ByLiWuzhou

By+Li+Wuzhou

More than 70 years later, the horrors of World War II (WWII) are being drawn back into the spotlight as disputing factions tackle the delicate and complex issue of“comfort women.”

In the 1993 Kono Statement, thenJapanese Chief Cabinet Secretary yohei Kono acknowledged that the Japanese Government and its Imperial Army were involved in the capture of between 200,000 and 400,000 girls and women—so-called“comfort women”—during WWII, who were forced into sex slavery by Japanese army.

In a recent review of the Kono Statement, however, Japan suggested that it be issued as the result of a political compromise between the country and South Korea at that time. Released on June 20, the Japanese Government stated in the review that it was not possible to confirm that women were forcefully recruited, aiming to deny that the involvement of the implicated women and girls was involuntary.

This move “must cause tremendous agony to the women,” said Navi Pillay, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, on August 6. She urged Japan to issue a “comprehensive, impartial and lasting resolution” on the wartime sexual crimes of its troops.

Two weeks before Pillay made her remarks, on July 24, the UN Human Rights Committee released its concluding observations on the sixth periodic report on Japans implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. It requested that Japan make immediate and thorough efforts to redress the issue of wartime “comfort women.” The committee urged Japan to officially recognize its responsibilities, prosecute and punish perpetrators, and educate students and the general public about the issue, including adequate references in textbooks.

To uncover the historical truth behind the coercion and abuse of these women, Su Zhiliang, Director of the China Research Center on Chinese “Comfort Women” at Shanghai Normal University, has performed extensive research on the topic. As part of Sus mission to widely publicize the events of the time, he proposed that historical documents on “comfort women” be protected and registered on the Memory of the World Register, a UNESCO program launched in 1997 to preserve history through documents and other physical evidence.

China submitted an official application to register its documents on the 1937 Nanjing Massacre and “comfort women” on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register on June 10, and the application was accepted on June 12.

Survivors accounts

Su began his research on “comfort women” by chance. It was in 1992, while working as a visiting scholar at the University of Tokyo, that he learned from a Japanese colleague about the invading Japanese Armys first “comfort station”in Shanghai. The Japanese Government had deliberately concealed the issue until 1992, when it caught worldwide attention.

Upon returning to China, Su immediately started his investigation into the issue. However, he encountered many difficulties in his research: the Japanese Army had destroyed a large number of documents before its surrender, a majority of the victims had passed away, and many surviving “comfort women” and their descendants were reluctant to speak about their suffering.

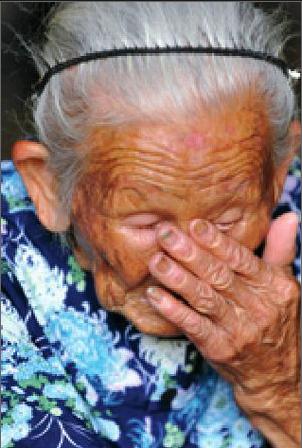

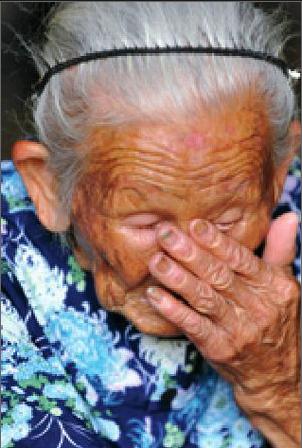

Despite the difficulties, Su managed to find 100 plus survivors who were willing to speak with him. Tan yadong, an elderly woman living in Wanru village, south Chinas Hainan Province, told investigators the tragic story of a girl named Ashi.

Having been raped by Japanese soldiers, Ashi became pregnant. Japanese soldiers tied her to a tree and cut open her belly. All “comfort women” in the station were ordered to line up along the road to watch the process. Tan told investigators that she has been haunted by this atrocity for decades, and it often gives her nightmares.

Other women also spoke to Su about similar traumatizing experiences. Zhang Xiantu, was forcibly drafted as a “comfort woman” at the age of 17. She shivered with fear upon seeing a Japanese man enter the room. Since then, her hands have continued to shake.

During his investigation, Su also learned that in the summer of 1942, soldiers in the 56th Division of the Japanese Army rushed to a busy area in Mangshi, yunnan Province, capturing more than 50 women of the Dai ethnic group to serve as “comfort women.”None of the women came back alive.

Su and other investigators recorded these survivors testimonies in two books, Studies on the “Comfort Women,” and Sex Slaves of the Japanese Troops: A True Account of Chinese “Comfort Women.”From these survivors combined retellings, Su learned that “comfort women” were, first and foremost, deprived of freedom. Often, a woman was raped by Japanese soldiers several or even dozens of times a day. Thus, some unyielding women committed suicide. Those resisting rape, attempting to escape, or who contracted serious venereal diseases or became pregnant were killed. By the time the war had ended, no more than one fourth of “comfort women” had survived.

For those who made it out alive, survival itself has not been an easy task. Many are looked down upon by people around them. Some have lost fertility. Others have refused to marry because of their bad memories.

An act of state

By calling them “comfort women,” said Su, the Japanese Army intended to mislead the world into thinking that these women were military prostitutes, and disguise the nations war crime of forcing women into sexual slavery. He added that this also added insult to injury for the victims, many of whom were later discriminated against by society and defamed.

The Japanese army abused a large number of women from China, Korea, Southeast Asian countries and even some from Europe and North America, said Su. The “comfort women” system was an “institutionalized government crime, and the most painful record in the history of women around the world,” he said.

Few “comfort women” are still alive today. Though some have demanded compensation from Japan, their requests are continually refused by the Japanese Government with various excuses; once, the government said that recruiting “comfort women” was not an official act of state.

yet Su said many scholars studying the issue, including himself, are able to present a large amount of evidence proving that the forceful recruitment of “comfort women”was an act orchestrated by the Japanese Government and troops. He said that he has spent 20 years reading documents ranging from old newspaper clippings to documents kept by Japanese Government agencies and the army, to study the matter.

After Japan set up the first “comfort station” in Shanghai in 1932, one of the first in Asia, Japan led a full-scale invasion of China in 1937. Sus study revealed that the Japanese Army set up “comfort stations” on occupied land in more than 20 Chinese provinces, enslaving an estimated minimum of 200,000 Chinese women.

“In the beginning, I did not expect Japans‘comfort women system to be so well-established. It involved Japans Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of the Navy, the Ministry of War and the invading Japanese Army,” he said.

“‘Comfort stations were set up for army divisions, companies, detachments and even squads. There were even rules on how to transport and finance the stations,” said Su.

Recently, the Jilin Provincial Archives publicized more than 100,000 documents left behind by the invading Japanese Army. Su studied the archives, finding more than 40 documents related to “comfort women,”one of which details how the Japanese Army set up “comfort stations” with public funds.

“Documents from the Central Bank of the puppet Manchukuo regime show that Unit 7990 of the Japanese Imperial Army spent 532,000 yen ($4,972) in four months to set up ‘comfort stations,” Su said, noting that back then, the monthly salary of a Japanese second lieutenant was only a few dozen yen (less than $1). The spending related to “comfort stations” was also reported to the command centers of relevant Japanese troops and military police officers, which revealed that the actions were approved by the Japanese Army.

According to Su, historical files relating to the “comfort women” submitted to the UNESCO Memory of the World Register include 29 groups of documents from five major sources—namely, the Japanese Kwantung Army stationed in the northeastern part of China, the police force in the Shanghai International Settlement, the puppet regime of Wang Jingwei, the Central Bank of Manchou and the written confessions of Japanese war criminals.

These documents clearly record Japans crimes related to the forced recruitment of the women, the living conditions in “comfort stations” and the number of Japanese soldiers frequenting them, as well as the ratio of Japanese soldiers to “comfort women” and details of gruesome rapes.

“These materials have proved, from various perspectives, that the forceful recruitment of ‘comfort women was an official act carried out by the Japanese Government and the Army,” said Su.