A Global Factory Relay?

2014-09-23ByYuLintao

By+Yu+Lintao

India is becoming an increasingly competi- tive player in the race to become the worlds next major manufacturer. With a population rivaling that of China and much cheaper labor, Indias demographics are highly favorable—statistics show that young people under the age of 26 comprise about half of Indias population of 1.2 billion.

Last month, in his speech on Indias Independence Day on August 15, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi invited the worlds business leaders to open up shop in the country. “Sell the products anywhere in the world but manufacture here...We have the power,” Modi said.

The new Indian prime minister seems to be striving to turn India into the next factory of the world. Observers said it is reasonable for Modi—who values Chinas development experiences—to prioritize the manufacturing sector. However, if they wish to fulfill their ambition to take hold of the baton from China, India will need to seek out Chinas expertise and find ways to cooperate along the road to becoming a manufacturing center.

The dilemma of transition

Indian people have widely admired the success of Gujarat, known as Indias Guangdong Province and the place where Modi made his name. The coastal Indian state, which accounts for about one twentieth of the countrys population, produces around 16 percent of its industrial output and more than one fifth of its exports. Those who cast their ballots for Modi also have pinned big hopes on the new prime ministers ability to apply his governing experience to the whole country.

As Indias advantages in the manufacturing world emerge, Indian media has begun calling for efforts to replace the ubiquitous “made-inChina” tag with “made-in-India.”

Wang Haixia, a research fellow on Indian studies with China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations (CICIR), said Indias race to become a manufacturing powerhouse is realistic but not without its challenges.

“Indeed, India has a large and growing working age population. But its economic growth has slowed down in recent years on top of high unemployment. At this particular moment, it is reasonable for Modi to promote the growth of manufacturing—a task that would also create more jobs,” Wang said. “In addition, a strong manufacturing sector could help India to boost exports, rebalancing its trade deficit with other countries.”

As a country where English is spoken widely, India was also favored by some foreign investors—especially those from the West—to have the language advantage in becoming a global center of manufacturing.endprint

Despite the favorable conditions, observers said the investment climate in India is less positive.

“Corruption and poor administrative efficiency in India are widely known, and problems relating to land acquisition and resettlement there are always nerve-wracking,”said Mei Xinyu, a senior researcher at the Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation, a think tank affiliated with the Ministry of Commerce.

In 2005, South Korean steel magnate Pohang Iron and Steel Co. Ltd.(POSCO) signed a contract with the Indian Government to build a factory in Orissa with an annual output of 12 million tons of steel. The project was supposed to include$1.2 billion of South Korean investments and was then the largest foreign direct investment in India. If completed, the steel plant would have become the third largest in the world. However, eight years after signing the contract, obstacles continued to prevent land acquisition for the project. POSCO finally abandoned its investment plan in 2013.

Mei said similar cases like the POSCO project are common in India. “Such politi-cal risks in India are greater than those in most other countries. We should never underestimate the challenges of industrial investment in India.”

Apart from the political factors, the countrys poor infrastructure is another major bottleneck in its ability to attract foreign investment to its manufacturing sector.

The vast electricity blackout in 2012 highlighted Indias shoddy infrastructure. But on top of the outdated power grids, a poor transportation system and communication infrastructure also mars the countrys image. According to the Global Competitiveness Report 2013-14 issued by the World Economic Forum, despite being an economic heavyweight, the global competitiveness of Indias infrastructure ranks the 85th, even below Sri Lanka and Ecuador.

In addition, inadequate basic education harms what would otherwise be an advantageous demographic makeup. A report by U.N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization released in the beginning of 2014 says India currently has 287 million illiterate adults, the largest population globally and 37 percent of the world total. Even after completing four years of school, 90 percent of Indian children from poorer households remain illiterate. This also holds true for around 30 percent of children from poorer homes despite receiving five to six years of schooling.endprint

Learning and progressing

To turn its vast population and other economic hurdles into comparative advantages, India could learn from and cooperate with China—a proven manufacturing power and important neighbor—on its road to becoming a global manufacturing powerhouse.

Lan Jianxue, an associate researcher with the China Institute of International Studies, said that while India traditionally stressed its service industry, China took the path of developing its manufacturing sector and, as such, each country developed its own set of strengths. In addition, China started its reform and opening-up policy a little earlier than India, allowing it to develop relatively faster and accumulate more experience in manufacturing.

Chinas manufacturing advantages—including technology and capital—could be of use in Indias own path to development, said Lan.

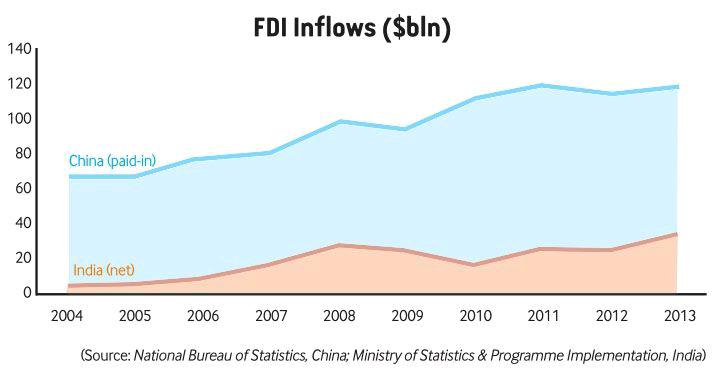

Wang of CICIR told Beijing Review that China views India as a vast potential market and an ideal investment destination. At the same time, as China undergoes a wave of industrial upgrading, manufacturing businesses are actively looking for investment opportunities in other countries.

“India lacks both the funds and the experience to construct extensive infrastructure; thus, teaming up with China is key to realizing Indias ambitions,” Lan said to Beijing Review.

For the past several years, China-India relations have improved quickly. Last year, the government heads of the two countries exchanged visits within a 12-month period for the first time ever, with Chinese Premier Li Keqiangs visit to New Delhi being his first foreign trip since taking office. Not long ago, during the 2014 BRICS summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping invited Indias new Prime Minister Modi to take part in the 2014 APEC Summit, which will be held in Beijing this autumn. It is the first time that an Indian leader was invited to attend the APEC Summit; meanwhile, it was reported that President Xi will travel to New Delhi in mid-September.

New initiatives

The “one road, one belt” strategy—namely the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road recently proposed by China—also creates a cooperation platform for enhancing economic ties between China and India.

In a recent interview with Indian media outlet The Hindu, Gao Zhenting, Counsellor at the Department of International Economic Affairs of the Chinese Foreign Ministry, said China and India could both benefit from the strategy and that Beijing wants India to play a key role in the initiative. “On maritime cooperation, we would like the participation of all ports along the Maritime Silk Road, with priority to be given to establishing special economic zones and industrial parks in these areas,” Gao said in the interview.endprint