Ink Blossoms

2014-07-28

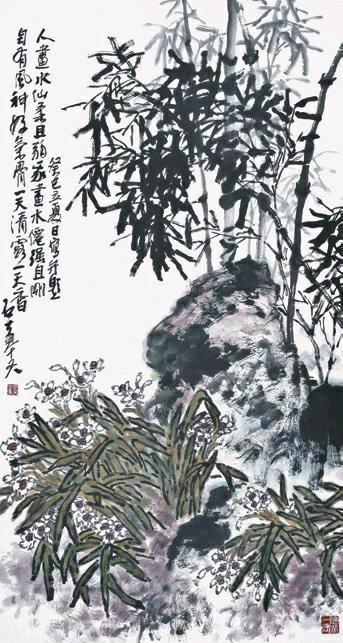

In Guo Shifus world, bright, flourishing peonies rest delicately atop indiscriminately outlined—yet purposefully placed—leaves. His masterful calligraphy says more than the words themselves, brush marks looping and trailing each other in a time-worn dance. Guos is a world that knows no age or bounds; in his paintings, one can see a deliberate combination of art genres, all of which saw preeminence at one time or another in Beijings past.

Born to an art family in the capital city in 1945, Guo learned his trade at a time when Chinese art was undergoing revolutionary changes. Many famous masters of their crafts were working to revive traditional Chinese ink painting with new thoughts and aesthetic standards. Naturally, Guo was deeply influenced by this revival at a young age. His art education began early on, when one day, while still a child, Guos father gifted him a finely printed album of The Paintings of the Imperial Palace. From that day forward, his father instructed his painting practice every day. Guos father was strict with his children; these first lessons laid an important and solid groundwork for themes that would be often repeated later in his art.

At that time, in the early 20th century, Beijing was home to many multitalented artists. They exchanged artistic works and thoughts and, as time went on, gradually evolved the then-prevailing genre of traditional ink painting. At the introduction of his father, Guo was swept into this circle of Beijing artists in the mid-century and made friends with many painters. This gave him a first taste of the prominent style of the time—cultured, elegant ink portraits of ornate birds and overflowing flowers. The bird-and-flower genre has distinctive features that are neither passed down from the formalistic traits of the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), nor from realistic Western oil painting styles of the time.

Chinas great scholar Wang Guowei (1877-1927) once argued that the difference between Chinese and Western art was that “the loveable is not believable, and the believable is not loveable.” During his childhood, Guo had been acutely aware of these differences in nature as portrayed by Chinese and Western paintings. He practiced imitating masterpieces from both China and abroad. At that time, too, the majority of Chinese artworks tended to imitate trends in the West, and oil paints prevailed over ink. Some radical Chinese artists even suggested abandon-ing traditional styles of Chinese art completely. But Guo understood that Chinese culture was a precious legacy left behind by his ancestors, and needed to be preserved and passed down throughout the generations.endprint

Drawing on the past

Guos works are both vivid and bold. His genre—traditional ink painting—can be traced back to the Song Dynasty (960-1279), when the freehand brushwork of flowers and birds originated. During the following centuries, most notably during the Ming and Qing dynasties (14th-19th centuries), this style reached its peak of popularity. By the 20th century, many artists attempted to revive and improve the traditional technique by absorbing Western art theories and practices and combining the two. Beginning in the 1980s, Chinese art again made profound changes under the influences of Western contemporary art, further clouding out traditional ink painting styles.

Guo, for his part, still insists on creating paintings in the old way. Today, after decades of persistent effort and painstaking practice, Guo has made remarkable achievements in the traditional art world, making his distinctive mark on the cultural heritage of ancient masters. In fact, he is widely recognized as one of the best contemporary painters to have achieved such a unique status. When traditional ink painting was on the decline in Beijing, Guo revived it, and rebuilt a taste for its distinctive characteristics.

Thus, Guos genre also places particular value and significance in the process of change. Throughout his work, Guo consistently showcases progressive techniques and establishes his skill by intertwining inspirations from treasured ancient art with modern-day subject matter. These pieces integrate classical arts essence with a flair that is distinctly his own. It is apparent that the charm and cultural value of Guos works are thus fruits of his unending appreciation for timeless beauty.

In Guos art, one cannot help but see the shadows of famous art masters: Qi Baishi (1864-1957), Li Kuchan (1899-1983), Wu Changshuo(1844-1927), and Chen Banding (1876-1970) have all influenced his canon. He restructures these traditional elements with skill, using the wisdom and experience of artists past to bring details in his own work to life.

A deep understanding of Chinese philosophy, too, lies behind each brush stroke in his pieces. For example, Guo has mastered the principles and true meaning behind “traditional fine art,” which relies heavily on balance and harmony. In his childhood, Guo would practice writing characters from classical books and gradually understood the ancient philosophies contained in these tomes. Guo inherited a way of thinking that had been passed down for thousands of years by the greatest Chinese minds.endprint

It is widely accepted that Chinese classics are the key to carrying on the intangible aspects of the culture. An enlightened way to look at and think about the world is contained in such paintings. Guo has long understood the precious value inherent in these works, and regardless of their popularity, continues to express the unique Chinese perspective on nature and humanity through his art.

Each of Guos paintings is a representation of both the present and the past. Fresh reflections on present-day life mesh with practiced and stylized symbols of beauty. As he noted, preserving the memories of history is a precondition for cultural development—and as tradition is well-respected, preserved and apparent in Guos art, his paintings therefore contain profound philosophical meaning and reflection.

The brush and ink represent the core spirit of the Chinese people, formed over a long period of historical and artistic evolution. Guo is thus very particular with the way he uses these tools. To him, they possess unique intellectual and spiritual inspiration.

Guo learned not only from Beijing painters, though, but from the bird-and-flower painting masters of 1,000 years ago. Though he reimagines the same ordinary objects as his predecessors, like plum blossoms, orchids, and bamboo stems, his unique aesthetic taste imbues his works with a new vibrancy and meaning. Once, at the age of 50, Guo noted that the field of bird-and-flower painting does not lack masters, so it is difficult to make a breakthrough in this field.

Guos career as an artist and traditional ink painter has spanned the decades, showcasing the sensibility, beauty, and imagination behind Chinese art. It will continue to progress only through continued innovations like Guos, applying new concepts to traditional art forms and helping them to blossom.endprint