Healing of Stoma After Magnetic Biliary-Enteric Anastomosis in Canine Peritonitis Models△

2014-04-20JianhuiLiLongGuoWeijieYaoZhiyongZhangShanpeiWangShiqiLiuZhiminGengXiaopingSongandYiLv

Jian-hui Li , Long Guo, Wei-jie Yao,, Zhi-yong Zhang, Shan-pei Wang, Shi-qi Liu, Zhi-min Geng, Xiao-ping Song, and Yi Lv,*

1Department of Surgical Oncology, Shaanxi Provincial People’s Hospital (The Third Affiliated Hospital of the School of Medicine Xi’an Jiaotong University), Xi’an 710068, China

2Research Institute of Advanced Surgical Technology and Engineering, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an 710061, China

3Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an 710061, China

BILE-ENTERIC anastomosis is a mature method in treating many bile duct diseases. However, due to acute inflammation, one-stage repair for bile duct injury is difficult to be achieved after biliary tract surgery, especially beyond 24 hours. The majority of bile duct injury cases occur in both laparotomy and laparoscopic surgery.1,2Traditional external biliary drainage often increases the duration of hospital stay and imposes considerable financial burden on the patients. In addition, secondary surgery always requires high suturing technique, and has a high failure rate. It may be followed by serious complications even when the continuity is successfully repaired.2-4

Since the first report of magnetic compression anastomosis technology by Obora et al5and Kanshin et al6in 1978, its feasibility and value in some complex surgical cases involving several systems have been continuingly demonstrated in both clinical application and experimental researches.6-10The Research Institute of Advanced Surgical Technology and Engineering of Xi’an Jiaotong University has also invented a series of magnetic apparatuses for anastomosing vessels and ducts of hepatobiliary system, including a biliary-enteric anastomosis stent.11In a previous experiment, we confirmed the feasibility of the stent and achieved satisfactory outcomes.11In this study, we further investigated the anastomotic effects of this technology and compared it with traditional suture anastomosis in tissue healing in a canine model of bile duct injury and bile peritonitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Magnetic anastomosis stent

Originally designed biliary-enteric anastomosis stents were applied, which is composed of two magnetic rings (A and B), a magnetic cone and a catheter. The magnetic rings are made of neodymium iron boron, and the cone is made of FeCr12 soft magnetic alloy. The outside diameters of the rings are 7 mm and the inside diameters of magnetic rings A and B are 3.8 mm and 4.4 mm respectively. A hole was bored at the center of the magnetic cone, with the same inside diameter as ring A and the diameters of the undersurface and the apical side being 7 mm and 6 mm, respectively. All those magnetic materials are plated with titanium film on the external superficies. Magnetic ring A and the magnetic cone are glued to the lateral aperture of the catheter with cyanoacrylate (Fig. 1). The maximum magnetic intensity of the stent for the horizontal axis is 70 mT and the magnetic force between the two rings is 6.4 N, 3.3 N, and 1.7 N for the distance of 0 mm, 1 mm, and 2 mm, respectively.

Animal model

Thirty-two mongrel dogs from the experimental animal center of Xi’an Jiaotong University Health Science Center were used regardless of gender, with body weight of 15-20 kg. The experimental protocols for this animal study were approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Xi’an Jiaotong University.

Surgical procedure

As the first step, bile duct injury and bile peritonitis models were established. After being fasted for 12 hours and put on a drip for 4 hours, the dogs were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of 2.5% thiopental (25 mg/kg). After they were prepared with povidone iodine and draped with sterile towels, a median abdominal incision was made. The cystic duct and the distal end of the common bile duct were ligated. A small opening was made on the proximal portion of the common bile duct through which a small catheter was inserted and fixed below the surface of the skin. Five days later, as the common bile duct was dilated, the catheter was pulled out subcutaneously.

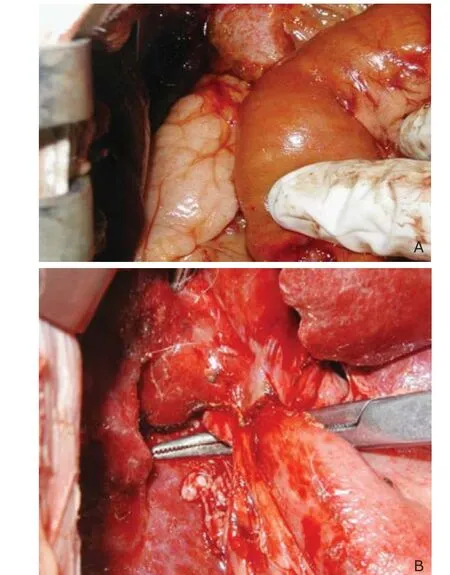

The 32 dogs with acute bile duct injury were randomly assigned to two groups: group A (n=16) anastomosed with magnetic stents, and group B (n=16) with traditional manual suture. Anastomoses were performed 48 hours after the catheters were removed, when bile peritonitis was serious (Fig. 2).

The anastomosis was performed as previously described.11Briefly, after the dogs were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of 2.5% thiopental (25 mg/kg), prepared with povidone iodine, and draped with sterile towels, the original incision was extended below the right costal margin and the abdominal cavity was washed with normal saline. The jejunum was dissociated and cut off about 15 cm away from the ligament of Treitz, and the distal end was closed with suture. End-to-side anastomosis was done between the proximal end and the jejunum far away from the distal end. After the gall bladder was resected, the bile duct was cut off above the leakage spot. The distal jejunum was attached to the hepatic hilum.

Figure 3. Diagram of the process of magnetic cholangiojejunostomy.

In group A, after the stent was sterilized with ethylene oxide, the cone side of the stent with ring A was inserted into the proximal end of the bile duct, and the stump of the bile duct was ligated and fixed onto the catheter. After a small opening was cut, the other side of the stent was inserted into the jejunum. Ring B was placed into the jejunum along the catheter. As ring A and B coupled automatically, the intestinal wall and the end of the common bile duct were clamped between the two rings (Fig. 3). The catheter was fixed onto the skin.

In group B, the traditional retrocolic end-to-side Roux-en-Y cholangiojejunostomy was performed between the cut end of the common bile duct and the distal jejunal wall, using 6-0 prolene suture.

Peritoneal drainage tubes were placed in both groups and the abdomen was closed layer by layer. After operation, phenylbutazone (oral 0.2 g/d) and penicillin [intravenous drip 20 wU/(kg·d)] were administered to relieve pain and prevent postoperative infection. The catheter was removed on the 10th postoperative day in group A.

Observation indexes

The dogs were housed as previously described.11General status, peritoneal drainage, and leakage incidence after the operation were observed and recorded. Half of the dogs in each group were euthanized on the 30th day (group A1and group B1) and the others on the 90th day (group A2and group B2). The circumference of the stoma and that of the bile duct 2 cm above the stoma were measured to calculate the stenosis degree (stenosis degree=1-stoma circumference/ bile duct circumference 2 cm above the stoma). Additionally, the stoma tissue was harvested and fixed in 10% neutral formalin. Slices of stoma were observed with both light microscope (HE staining) and scanning electron microscope for histological changes.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 19.0 was used for the data analysis. All data were expressed as means±SD. Nonparametric tests were used for the statistical analysis in all cases. Inter-group differences were analyzed with Student’s unpaired t-test, u-test, F-test, and Fisher’s exact test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical follow-up outcomes

Common bile duct dilation (diameter increased to 7-8 mm) was observed in both groups. The bile duct wall appeared crisp and thicken with severe edema (Fig. 2). However, compared with group B, the process of sutureless anas- tomosis (group A) was relatively easy and prompt without any bile duct wall injury and bile leakage (Fig. 4).

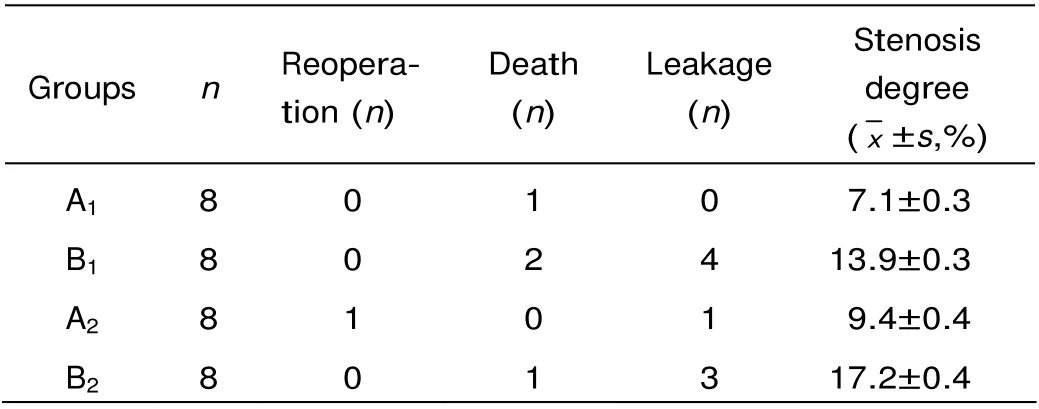

The magnets of group A were discharged along with feces 3-4 days after the catheter was removed. In group A1, 1 dog died of subdiaphragmatic abscess formed on the 12th postoperative day, with no obvious inflammation and bile leakage around the stoma. Due to stent shedding led by erratic fixing and imbedding of the stent on the 3rd postoperative day, one dog in group A2underwent a second surgery 24 hours after stent shedding. During the second operation, we noticed massive turbid abdominal dropsy, bile leakage, intestinal fistula, serious periangiocholitis, and intestinal invagination due to dragging by the magnetic stent. However, the stent was still fixed firmly on the stoma of the intestinal side. Altogether 7 cases in group B experienced bile leakage, one died of wound dehiscence on the postoperative 4th day and two of them who were complicated by intestinal fistula died on the 4th day and the 6th day respectively after surgery, the others healed after peritoneal drainage for 7-11 days (Table 1).

The stoma leakage rate was significantly higher in group B1than in group A1(u0.05=1.96, u=4.39>1.96, P<0.05), the stoma leakage rate was also significantly higher in group B2than in group A2(u0.05=1.96, u=2.29>1.96, P<0.05).

The stenosis degree was significantly higher in group B1than in group A1(t0.01(14)=2.977, t=7.347>2.977, P<0.01), the stenosis degree was also significantly higher in group B2than in group A2(t0.01(14)=2.977,t=8.194>2.977, P<0.01).

Figure 4. Biliary-enteric anastomosis by magnetic stent (A) and traditional manual suture (B).

Table 1. Postoperative outcomes of the dogs with bile duct injury and peritonitis

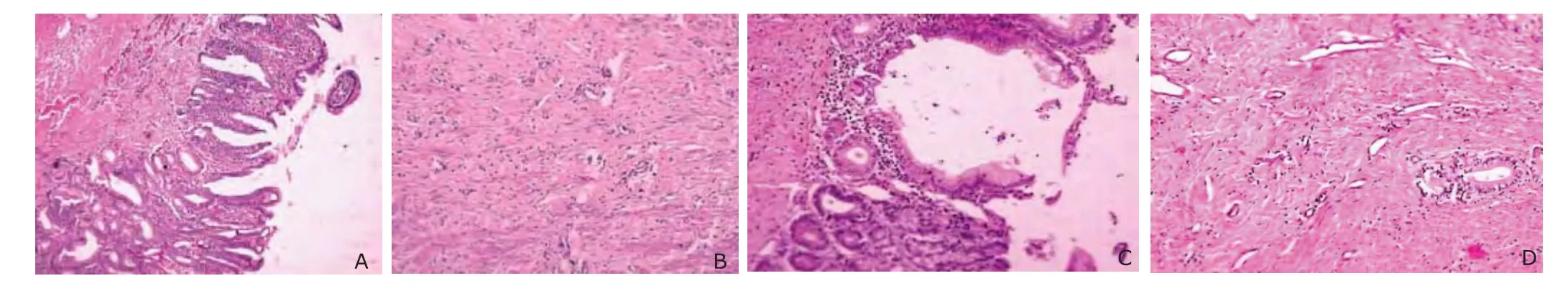

Histological observation

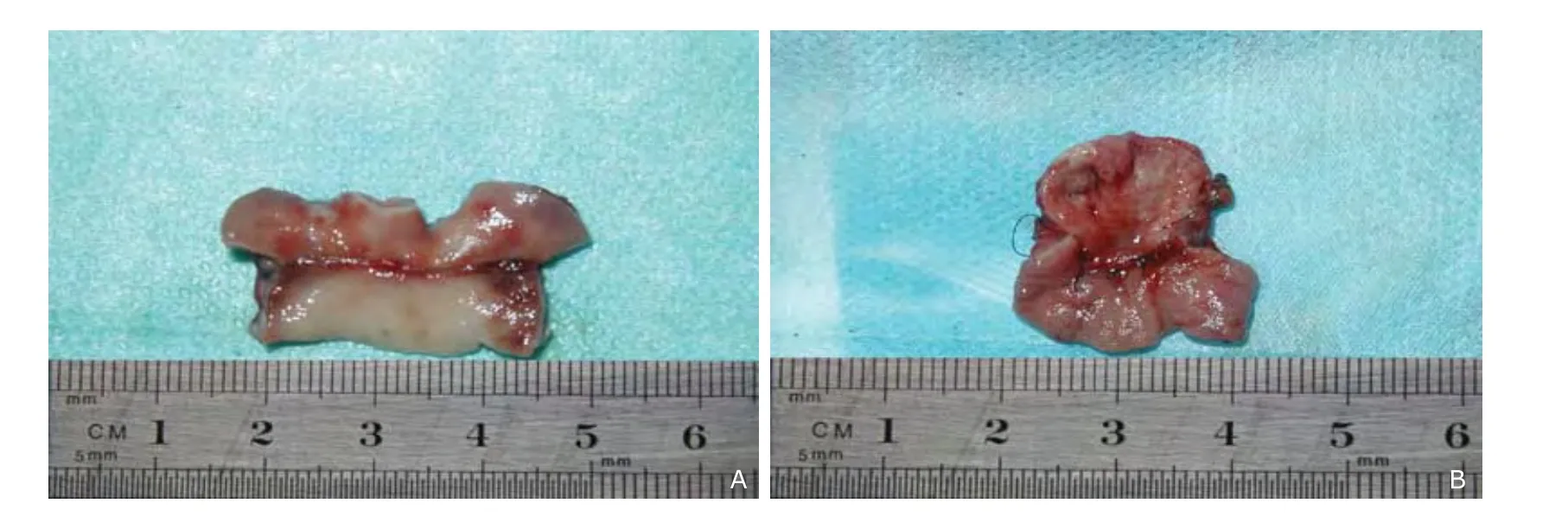

One month after the anastomosis, gross observation noticed continuous epithelia from the bile tract wall passing through the stoma in group A1(Fig. 5A). In contrast, serious adhesions and stenosis was found in the stomas in group B1, the suture line protruded into the duct cavity, making the lining epithelium more uneven (Fig. 5B). In groups A2and B2, the healing status of stoma was similar, except that the lining epithelium seemed more even in group B2than in group B1.

Histological observation under the light microscope revealed that a continuous epithelium migrating from the bile tract wall through the anastomotic stoma to the intestinal wall in group A1. Inflammation of the submu- cosal region was mild. Moreover, the submucous layer and muscular layer healed well and collagen fibers organized appropriately (Fig. 6A-B). In contrast, in group B1a large amount of inflammatory cells were distributed in the submucosa surrounding the stoma, including neutrophilic granulocytes, plasmocytes, and many lym- phocytes. The mucosa around the sutures was weak, with engorging small vessels and disorderly lining collagen (Fig. 6C-D).

In group A2, the epithelium between the bile tract and intestinal wall connected completely with a mucous layer well-distributed in thickness. Less inflammatory cells were found in the submucosa. The submucous layer and muscular layer healed completely, and collagen fibers organized appropriately (Fig. 7 A-B). In group B2, the epithelium between the bile tract and intestinal wall connected, with many inflammatory cells, especially lymphocytes, distributing in the submucosa. Although the submucous layer and muscular layer were healed, the collagen fibers was disorderly distributed and appeared helical, with hyalinization in some regions (Fig. 7 C-D).

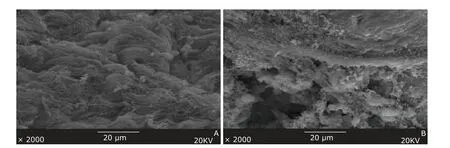

Histological examination under the electron microscope in group A1revealed that a continuous epithelium proliferated orderly and covered the anastomotic stoma completely. Fibroblast and collagen fibers were distributed orderly (Fig. 8A). In contrast, the stoma in group B1lacked continuity, with obvious line-shaped furrow. Partial suture was exposed to the lumen directly because the epithelium could not cover the suture completely. Disorder distribution of fibroblast and collagen fibers was observed (Fig. 8B). In group A2, the epithelium was smooth and neat in the stoma. In contrast, the epithelium in group B2was uneven with lots of cholate deposit although the epithelium was continuous basically. Fibroblast and collagen fibers were distributed more orderly in group A2than in group B2(Fig. 9 A-B).

Figure 5. Gross observation shows continuous epithelia from the bile tract wall passing through the stoma in group A1 (A) in contrast with uneven epithelium with serious adhesions and stenosis in group B1 (B).

Figure 6. Histological observation at the stoma under light microscope shows a continuous epithelium migration (A), well organized collagen fibers and mild inflammation in submucous layer and muscular layer in group A1 (B), in contrast with a discontinuous mucous layer (C), disorderly distributed collagen fibers with a large amount of inflammatory cells and engorging small vessels in submucous layer and muscular layer in group B1 (D). (HE×10)

Figure 7. Histological observation at the stoma under light microscope shows a thick well-distributed mucous layer (A), well organized collagen fibers and less inflammatory cells in submucous layer and muscular layer in group A2 (B), in contrast with a disorder mucous layer (C), disorderly distributed collagen fibers and many inflammatory cells in submucous layer and muscular layer in group B2 (D). (HE×10)

Figure 8. Histological observation at the stoma under electron microscope shows a continuous stoma with orderly epithelium proliferation and orderly distributed fibroblast and collagen fibers in group A1 (A); a discontinuous stoma with obvious line-shaped furrow and disorderly distributed fibroblast and collagen fibers in group B1 (B). (×20)

Figure 9. Histological observation at the stoma under electron microscope shows smooth epithelium and orderly distributed fibroblast and collagen fibers in group A2 (A); uneven epithelium and basically order-distributed fibroblast and collagen fibers in group B2 (B). (×2000)

DISCUSSION

Acute bile duct injury always results in short-term complications such as biloma, bile peritonitis, sepsis, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, external biliary fistula, cholangitis, liver abscess, etc. If not properly managed, these complications may be associated with mortality as high as 3%.12Hepaticojejunostomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis reduces the tension of anastomosis and provides good blood supply, therefore preferred in the treatment of duct transection injury. However, there is still a considerable incidence of anastomotic leakage after traditional hand-sewn choledochojejunostomy under the condition of abdominal infection.13Some researches manifested that the decrease of hydroxyproline in serum and tissue and dystrophia could influence the healing of intestinal stoma, while suture could aggravate the process of collagen degradation, ultimately inducing stomal leakage.14,15The same change may happen in choledochojejunostomy with bile peritonitis and cholangitis. Thus, stomal leakage under this condition is usually considered to be related not only with inflammation but also with anastomosis technique and suture injury. Sutureless magnetic anastomosis could eliminate or relieve the above-mentioned factors related to stomal leakage, except the state of inflammation.

Based on the results of this study, we can conclude that the magnetic anastomosis stent has more advantages compared with the manual suture anastomosis. The histological observation revealed increased submucous inflammation cells in the stoma of group B1, and some suture was exposed to the lumen, delaying the healing of the stoma. Furthermore, the pin hole brought by the suture may increase the full-thickness bile leaks into the stoma, finally causing stomal leakage and scarring. As a result, a second suture is needed in that region, probably inducing scarring and stoma stricture. The comparison of the histological results of group A and group B indicated that magnetic anastomosis could profit the tissue healing and decrease the incidence of complications at the stoma because of the sutureless nature.

In the previous study, we found the healing of bile duct presents scar healing, which is regarded as excessive heal. The histological process of healing manifestes long-time inflammatory exudation, delayed chronic inflammation, slowly moving mucous hyperplasia and repair, excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix, and massive synthesis of collagen fibers. The bile leaking into the submucosa could aggravate inflammation, stimulating macrophage proliferation, releasing a series of mediators of inflammation and cytokines, and leading to the active proliferation of fibroblast with strong ability of collagen synthesis. In addition, the inflammatory stimulation around the stoma and the long-time contraflow of intestinal juice may induce the stomal stricture. The ultrastructure under the electron microscope manifested that the mucous epithelium of bile duct healed relatively slowly, mucosa became thin with lower papillae and disorderly distributed epithelium, collagen presented dense and disorder arrangement, forming the shape of whirlpool and tuberculum.16,17

Compared with suture anastomosis, magnetic anastomosis presented better results in ultrastructure, which indicates that magnetic anastomosis stent does not induce degeneration and necrosis of tissue. As a result, the magnetic anastomosis stent can promote the healing of stomal tissue and decrease the formation of scar. The reason is not completely clear. Electron microscope observation of the stoma in group A1revealed that the stoma had healed but remained relatively weak and thin in the mucous layer, in contrast, the anastomotic stoma in group A2showed completely connected epithelium and well-distributed thickness in the mucous layer. Therefore, the mechanism of reconstruction of the biliary-enteric continuity by the magnetic anastomosis stent may be that cells creep and then heal along the wall of bile duct and intestinal canal as the magnetic rings squeeze and cut gradually. We presume that as the tissue between magnetic rings decreases until disrupts completely, distance between tissues reduces and the magnetic force increases gradually, anastomosis stoma will finally take form.

In conclusion, the magnetic anastomosis stent showed obvious superiority in healing of the stoma even under the circumstance of severe inflammation. Further research on delivering this magnetic stent by endoscope is necessary, as well as works for translating this magnetic biliary-enteric anastomosis stent into clinical use.

1. Karvonen J, Salminen P, Grönroos JM. Bile duct injuries during open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the laparoscopic era: alarming trends. Surg Endosc 2011; 25:2906-10.

2. Pesce A, Portale TR, Minutolo V, et al. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy without intraoperative cholangiography: a retrospective study on 1,100 selected patients. Dig Surg 2012; 29:310-4.

3. Walsh RM, Henderson JM, Vogt DP, et al. Long-term outcome of biliary reconstruction for bile duct injuries from laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Surgery 2007; 142:450-6.

4. Holte K, Bardram L, Wettergren A, et al. Reconstruction of major bile duct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dan Med Bull 2010 Feb [cited 2013 Jul 01]; 57:A4135. Available from: http://www.danmedj.dk/portal/page/portal/ danmedj.dk/dmj_forside/PAST_ISSUE/2010/DMB_2010_02/A4135.

5. Obora Y, Tamaki N, Matsumoto S. Nonsuture microvascular anastomosis using magnet rings: preliminary report. Surg Neurol 1978; 9:117-20.

6. Kanshin NN, Permiakov NK, Dzhalagoniia RA, et al. Sutureless anastomoses in gastrointestinal surgery with and without steady magnetic field (experimental study). Arkh Patol 1978; 40:56-61.

7. Lubashevskiǐ VT, Shabanov AM, Vasil’ev GS. The inflammatory-reparative processes in the implantation of the ureter into the bladder by using the mechanical forces of permanent magnets. Biull Eksp Biol Med 1993; 116:550-2.

8. Myers C, Yellen B, Evans J, et al. Using external magnet guidance and endoscopically placed magnets to create suture-free gastro-enteral anastomoses. Surg Endosc 2010; 24:1104-9.

9. Uygun I, Okur MH, Cimen H, et al. Magnetic compression gastrostomy in the rat. Ped Surg Int 2012; 28:529-32.

10. Wall J, Diana M, Leroy J, et al. Magnamosis IV: magnetic compression anastomosis for minimally invasive colorectal surgery. Endoscopy 2013; 45:643-8.

11. Li JH, Lü Y, Qu B, et al. Application of a new type of sutureless magnetic biliary-enteric anastomosis stent for one-stage reconstruction of the biliary-enteric continuity after acute bile duct injury: an experimental study. J Surg Res 2008; 148:136-42.

12. Karvonen J, Gullichsen R, Laine S, et al. Bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: primary and long-term results from a single institution. Surg Endosc 2007; 21:1069-73.

13. Pottakkat B, Vijayahari R, Prakash A, et al. Factors predicting failure following high bilio-enteric anastomosis for post-cholecystectomy benign biliary strictures. J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 14:1389-94.

14. Rico RM, Ripamonti R, Burns AL, et al. The effect of sepsis on wound healing. J Surg Res 2002; 102:193-7.

15. Li YS, Bao Y, Jiang T, et al. Effect of the combination of fibrin glue and growth hormone on incomplete intestinal anastomoses in a rat model of intra-abdominal sepsis. J Surg Res 2006; 131:111-7.

16. Geng ZM, Yao YM, Liu QG, et al. Mechanism of benign biliary stricture: a morphological and immunohisto- chemical study. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11:293-5.

17. Geng ZM, Zheng JB, Zhang XX, et al. Role of transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway in pathogenesis of benign biliary stricture. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 4949-54.

杂志排行

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal的其它文章

- Serum Levels of Interleukin-1 Beta, Interleukin-6 and Melatonin over Summer and Winter in Kidney Deficiency Syndrome in Bizheng Rats△

- Minimally Invasive Perventricular Device Closure of Ventricular Septal Defect: a Comparative Study in 80 Patients

- Expression of Peptidylarginine Deiminase 4 and Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Nonreceptor Type 22 in the Synovium of Collagen-Induced Arthritis Rats△

- Lipocalin-2 Test in Distinguishing Acute Lung Injury Cases from Septic Mice Without Acute Lung Injury△

- False Human Immunodeficiency Virus Test Results Associated with Rheumatoid Factors in Rheumatoid Arthritis△

- Arachnoiditis Ossificans of Lumbosacral Spine: a Case Report and Literature Review