MAOIST WACATION

2014-03-01TEXTANDPHOTOGRAPHSBYLIUJUE刘珏

TEXT AND PHOTOGRAPHS BY LIU JUE (刘珏)

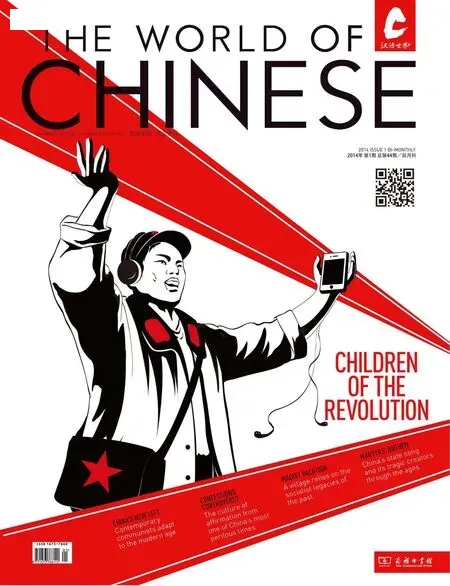

MAOIST WACATION

TEXT AND PHOTOGRAPHS BY LIU JUE (刘珏)

An oasis of Maoism in the market-oriented world

南街村的光荣与梦想

Decades ago it was common for families throughout China to place an image of Chairman Mao in the center of their homes. Today this is a rare sight in most Chinese homes, unless you happen to live in Nanjie Village (南街村). In fact, a portrait where Mao's smile beams from within the center of a radiant red sun is an alltoo-common decoration for each of the village's identical apartments. Such adornments were decided by the communal decree of the village committee, the portrait also serving as an electronic calendar and clock. On the right of the portrait, it says: “Mao Zedong is a human being, not a god.” Fair enough, however, immediately to the left, it states: “Mao Zedong Thought excels any god.”Nanjiers are familiar with this particular slogan: not only because they see it everywhere, but because it appears to be the guiding motto to their lives. While other parts of China went through the Reform and Opening Up in the early 80s, learning to embrace the market economy, Nanjie Village remained a collective and embraced Maoism. For a while, this fast track to communism was applauded throughout the country. However, when a model is largely ignored, it's not unfair to assume it has not been a resounding success, and Nanjie Village is still the last collective of its type in China.

Each year, up to half a million visitors from around the country (even around the world) come to admire this village's red culture as well as its lifestyle, which many villagers claim is heavenly. For starters, villagers are entitled to free medical care, housing, electricity, water, and gas. Furniture and essential electronic equipment are issued to every family. From the moment a child is born, the village arranges everything for them: free education from kindergarten to college and even graduate school. For those who fail the college entrance exam, the village funds vocational school. For every villager there is always a job waiting in one of the 26 different enterprises owned by the collective. While the outside world struggles with soaring real estate prices, medical bills, and shrinking job opportunities, all seems well in the leftist utopia that is Nanjie Village.

Built in 1992, there are two models for villagers' apartments: the 75-square-meter two-bedroom for two-generation families and the 92-square-meter three-bedroom apartments for three-generation families. Called “Happy Community”, this area currently houses over 960 families.

As to how all this was achieved, 62-year-old Party secretary of the village committee, Wang Hongbin (王宏斌) lauds the power of Maoism: “For decades, we have been committed to Mao Zedong Thought, using it to arm and educate our people. As a result, the collective economy is developed, and we are living a fairly comfortable life with common prosperity in the near future.”

Despite Wang's claims, it wasn't really Maoism that inspired him to start the collective, but it certainly helped maintain it. Red songs such as “The East is Red”, “The Voyage Depends on the Helmsman”, and “Socialism is Good” are broadcast daily, and everyone is encouraged to study Mao's works. Above all, devotion to the collective is highly promoted, or what they call “the spirit of the fool”(傻子精神)—a fool who does not care about individual gain or loss, instead devoting himself to the good of the collective. Villagers certainly need such spirit to make peace with their work; compensation is usually only few hundred RMB, regardless of performance.

On being asked about salary, Sheng Ganyu, director of the Publicity and Education Department for Nanjie explained that only 30 percent of villagers' benef i ts come as direct fi nancial compensation, the remaining 70 percent are benef i ts such as housing, education, food stamps, and vouchers that can be used in the market. “In order to set an example, all members of the village committee and leaders of enterprises have even lower salaries, only 250 RMB,” he says. “And they enjoy no other special treatment.” Two hundred and fi fty or 二百五 in Chinese also means “foolish”. Therefore, the cadres' salary is, quite intentionally, a gesture of devotion to the collective. They call themselves “two hundred and fi fty cadres” (二百五干部), serving the people wholeheartedly. When asked whether such low salaries damage motivation, director Sheng proudly says: “In the distinct environment of Nanjie Village where everyone is highly moral and responsible, I don't think they will have a problem—at least most of them won't.”

“It's def i nitely not enough!” said an employee at a sales company in Nanjie. “Our food stamps are just for fl our, steamed bread, and noodles; as to the vouchers, it's never enough and we have to buy everything with money like everywhere else.” With a job in sales, his salary is still fi xed at a couple of hundred.

When asked about the apparent mismatch of this arrangement, the employee sighed, explaining, “We don't mention incentives because we care more about devotion.” On being asked if a different arrangement might make him more devoted, he simply answered: “This is not a problem I can discuss,” and pointed me in the direction of the village committee, “Go ask them.” For those who are less “devoted”, working outside the village is common.

“The monthly welfare is only about 60kuaiand it takes at least 300 to survive. With other spending, the salary here is simply too low,” said a villager explaining his reason for abandoning the “heavenly” Nanjie Village; instead, he operates a small business outside, earning a monthly income of a few thousand RMB.

If those who are inside want to get out, then those who are outside want to get in. Nanjie currently employs over 10,000 outsiders in its various enterprises, more than three times the number of locals. Their salaries are higher (still only 1,000-2,000 RMB), but they don't get the other benef i ts. Among them is 20 year-old Zhang Yanli, who moved from an adjacent village to work as a tour guide at the local tourism company. Her job is to show visitors around and present them with a perfect“communist community in the making”, which she is not a part of. “Outsiders who are selected as outstanding workers for fi ve years in a row and have worked there for 10 years can be awarded the title of ‘honorary villager', and they will get the same benef i ts as the other villagers,”she explained. Although she is not sure if she wants to stay in the village for that long, it certainly strikes her as a good opportunity. While the village produces manyjobs for the area, some people express concern at such practices in a “communist collective”, comparing it to capitalism—with workers creating surpluses and decreasing value.

Over 30 elderly people live in the senior home in Nanjie.enjoying free medical care and seen after by the collective

As to the 250 RMB salaries of the village cadres, it has long been regarded as merely a slogan, with many villagers suspecting corruption. In 2003, director of the village Wang Jinzhong died of a heart attack. It has been alleged that at least 20 million RMB in cash and multiple deeds with his name were found in a safe in his off i ce. Villagers attending his funeral told a journalist fromSouthern Metropolis Dailythat several women with small children showed up, claiming to be mistresses who bore his illegitimate children, asking for a share of the money. Wang Hongbin later denied such claims, stating that only 30,000 in cash was found. Despite the suspicion, there are those who believe in the 250 spirit. In 2007, Li Na, Mao Zedong's daughter, personally donated 100,000 RMB to Nanjie, asking for it to be used to better the living conditions of those in the leading posts. In Wang's letter to her, he thanked her for her devotion, saying he believed it to be a great encouragement for Nanjie to continue its work for its communist community. A little cash certainly seems to inspire devotion.

Wang has been leading the village for the past 37 years and was the paramount advocate in its creation. Back in 1980, when traditional farming was still the main livelihood for the villagers, he led the establishment of a fl our mill and a brickyard, in which he personally contributed funds. The next year, when rural reform and the household contract system began, the mill and brickyard were contracted to individuals. However, the two small factories as well as local agriculture were a failure under such a contract; villagers chose to leave the land uncultivated and the contractors neglected to deliver prof i ts or paychecks. Starting in 1984, Wang decided to take back the factories and the land, a sort of micronationalization if there were such a thing. On the morning of March 14, 1986, villagers gathered in front of an announcement issued by the village committee and learned that they were all in this together: now all villagers tended the land jointly while the rest of the labor supply would be arranged to work in the factories. In return, thevillage would provide all members with food. This marked the beginning of Nanjie Village as a collective.

A favorite hangout for the villagers and neighboring residents, Chaoyangmen city gate was part of a 50 million budget project to surround the entire village with walls. The plan was later aborted due to a lack of funds.

Nanjie Village takes great pride in its reputation as “The Hundred Million Red Village” (红色亿元村). From food, drink, and medicine to printing, chemicals, and tourism, the collective that is Nanjie Village Group claimed to have an annual output value of over one billion RMB as early as the 1990s. It is said that the village developed at a speed faster than the special economic zones, such as Shenzhen. The rapid growth of the village enterprises coincided with Maoist fervor. It seems that Mao Zedong Thought has taken an effect after all, but perhaps not in the way claimed. In a village speech in 1990, Wang Hongbin said:“Right now, it's easy for Nanjie to get a loan…Authorities of different levels all want to make a Nanjie model…Governmental funds will come our way, millions of RMB. We have to grasp every opportunity and give Nanjie a total makeover in the next two to three years.”Wang was spot on. In the surging wave of national reform, Maoism became a reassurance against the worries of capitalist invasion and brought him huge sums of bank loans and funding facilitated by the government. Before long, Nanjie had begun its ascent. Alongside those of Mao, it seemed the village was also invoking the ideas of Deng Xiaoping: for Nanjie, getting rich was glorious.

Backed up by loans, Nanjie did not just stop at building factories and setting up companies. Apart from the identical apartment buildings for all the villagers, publicfacilities in Nanjie are top-notch: fi ve park areas, a zoo, a small artif i cial mountain set with bridges over a moat; a grand mosque was built for Hui Muslims who make up 10 percent of population, as well as a large swimming center. It also boasts a city gate tower and city walls—not bad for a place with a little over 3,000 residents. Wang made a name for himself along the way, becoming a “national model worker” and an outstanding Party member of Henan Province. He has also repeatedly been selected as a National People's Congress representative.

Maybe he was bewildered by all the possibilities (or perhaps his own delusional nature), but in 1999, against many objections from other members in the village committee, Wang decided to fund a study to invent a perpetual motion machine—largely considered a complete and utter scinetif i c impossibility. A few months later when the machine was“done”, three brand new Audis were bought for tests. After their engines were removed and the magic machine installed, as one might imagine, nothing happened—with that, 20 million RMB went to waste. It was only four years later that Wang publically stated that he was deceived by charlatans and expressed regret. Always a lovable fi gure among the villagers, he was forgiven and was never called to account for the loss.

The days of rum and honey in Nanjie lasted for a while, that is, until the loans caught up with them. At 73, Zhu Gengxi enjoys the sunshine on the steps of the grand city gate but is worried about the future. “It looks well on the outside, but that's not the truth. If only we had built all these with our own effort,” he says. “Now that we owe the bank so much money, we can't even pay back the interest.” In a study conducted by sociologist Feng Shizheng at the Renmin University of China, it was found that the increase in Nanjie's output correlates exactly with its bank loans—the loans dangerously higher than the prof i ts. At its most extreme, in 1998, the ratio was nearly seven to one. “The rapid growth of Nanjie is the result of bank loans rather than self-generation,” said Feng, adding, “a typical case of high growth but low eff i ciency.” Later, as the state-owned commercial banks went through a transformation and turned into shareholding enterprises, Nanjie was put on a black list for future loans due to its bad credit history. Today, the village claims to have minimized its debt to lower than 400 million RMB and continues to try to pay back each and every lastkuaiit blew.

Most ordinary residents in Nanjie get on with their daily lives without too much complaint. This does not mean they are unaware of the dissonance in which they live. But when unable to make changes to their environment, people often fi nd ways to make peace. Zhang Wenjian, a 58-year-old local supermarket employee is content with his current status; his salary is not high, but it's enough. “The world is never equal,” he says, “so there's no point making comparisons to others. I have a job, food on my table, and a roof over my head. It's everything I need.” And if this is what communism means to the village of Nanjie, then the village is certainly living the dream.